Laurie Halse Anderson

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Excesss Karaoke Master by Artist

XS Master by ARTIST Artist Song Title Artist Song Title (hed) Planet Earth Bartender TOOTIMETOOTIMETOOTIM ? & The Mysterians 96 Tears E 10 Years Beautiful UGH! Wasteland 1999 Man United Squad Lift It High (All About 10,000 Maniacs Candy Everybody Wants Belief) More Than This 2 Chainz Bigger Than You (feat. Drake & Quavo) [clean] Trouble Me I'm Different 100 Proof Aged In Soul Somebody's Been Sleeping I'm Different (explicit) 10cc Donna 2 Chainz & Chris Brown Countdown Dreadlock Holiday 2 Chainz & Kendrick Fuckin' Problems I'm Mandy Fly Me Lamar I'm Not In Love 2 Chainz & Pharrell Feds Watching (explicit) Rubber Bullets 2 Chainz feat Drake No Lie (explicit) Things We Do For Love, 2 Chainz feat Kanye West Birthday Song (explicit) The 2 Evisa Oh La La La Wall Street Shuffle 2 Live Crew Do Wah Diddy Diddy 112 Dance With Me Me So Horny It's Over Now We Want Some Pussy Peaches & Cream 2 Pac California Love U Already Know Changes 112 feat Mase Puff Daddy Only You & Notorious B.I.G. Dear Mama 12 Gauge Dunkie Butt I Get Around 12 Stones We Are One Thugz Mansion 1910 Fruitgum Co. Simon Says Until The End Of Time 1975, The Chocolate 2 Pistols & Ray J You Know Me City, The 2 Pistols & T-Pain & Tay She Got It Dizm Girls (clean) 2 Unlimited No Limits If You're Too Shy (Let Me Know) 20 Fingers Short Dick Man If You're Too Shy (Let Me 21 Savage & Offset &Metro Ghostface Killers Know) Boomin & Travis Scott It's Not Living (If It's Not 21st Century Girls 21st Century Girls With You 2am Club Too Fucked Up To Call It's Not Living (If It's Not 2AM Club Not -

2020 May June Newsletter

MAY / JUNE NEWSLETTER CLUB COMMITTEE 2020 CONTENT President Karl Herman 2304946 President Report - 1 Secretary Clare Atkinson 2159441 Photos - 2 Treasurer Nicola Fleming 2304604 Club Notices - 3 Tuitions Cheryl Cross 0275120144 Jokes - 3-4 Pub Relations Wendy Butler 0273797227 Fundraising - 4 Hall Mgr James Phillipson 021929916 Demos - 5 Editor/Cleaner Jeanette Hope - Johnstone Birthdays - 5 0276233253 New Members - 5 Demo Co-Ord Izaak Sanders 0278943522 Member Profile - 6 Committee: Pauline Rodan, Brent Shirley & Evelyn Sooalo Rock n Roll Personalities History - 7-14 Sale and wanted - 15 THE PRESIDENTS BOOGIE WOOGIE Hi guys, it seems forever that I have seen you all in one way or another, 70 days to be exact!! Bit scary and I would say a number of you may have to go through beginner lessons again and also wear name tags lol. On the 9th of May the national association had their AGM with a number of clubs from throughout New Zealand that were involved. First time ever we had to run the meeting through zoom so talking to 40 odd people from around the country was quite weird but it worked. A number of remits were discussed and voted on with a collection of changes mostly good but a few I didn’t agree with but you all can see it all on the association website if you are interested in looking . Also senior and junior nationals were voted on where they should be hosted and that is also advertised on their website. Juniors next year will be in Porirua and Seniors will be in Wanganui. -

The History Group's Silver Jubilee

History of Meteorology and Physical Oceanography Special Interest Group Newsletter 1, 2010 ANNUAL REPORT CONTENTS We asked in the last two newsletters if you Annual Report ........................................... 1 thought the History Group should hold an Committee members ................................ 2 Annual General Meeting. There is nothing in Mrs Jean Ludlam ...................................... 2 the By-Law s or Standing Orders of the Royal Meteorological Society that requires the The 2010 Summer Meeting ..................... 3 Group to hold one, nor does Charity Law Report of meeting on 18 November .......... 4 require one. Which papers have been cited? .............. 10 Don’t try this at home! ............................. 10 Only one person responded, and that was in More Richard Gregory reminiscences ..... 11 passing during a telephone conversation about something else. He was in favour of Storm warnings for seafarers: Part 2 ....... 13 holding an AGM but only slightly so. He Swedish storm warnings ......................... 17 expressed the view that an AGM provides an Rikitea meteorological station ................. 19 opportunity to put forward ideas for the More on the D-Day forecast .................... 20 Group’s committee to consider. Recent publications ................................ 21 As there has been so little response, the Did you know? ........................................ 22 Group’s committee has decided that there will Date for your diary .................................. 23 not be an AGM this year. Historic picture ........................................ 23 2009 members of the Group ................... 24 CHAIRMAN’S REVIEW OF 2009 by Malcolm Walker year. Sadly, however, two people who have supported the Group for many years died during I begin as I did last year. Without an enthusiastic 2009. David Limbert passed away on 3 M a y, and conscientious committee, there would be no and Jean Ludlam died in October (see page 2). -

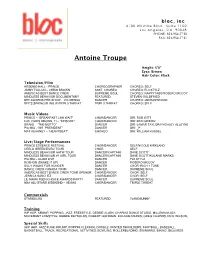

Antoine Troupe

bloc, inc. 6100 Wilshire Blvd., Suite 1100 Los Angeles, CA 90048 PHONE: 323-954-7730 FAX: 323-954-7731 Antoine Troupe Height: 5’8” Eyes: Brown Hair Color: Black Television/Film ARSENIO HALL - PRINCE CHOREOGRAPHER CHOREO: SELF JIMMY FALLON – CHRIS BROWN ASST. CHOREO CHOREO: FLII STYLZ AMERICAS BEST DANCE CREW SUPREME SOUL CHOREO: NAPPYTABS/ROSERO MCCOY MINDLESS BEHAVIOR DOCUMENTARY FEATURED STEVEN GOLDFRIED BET AWARDS PRE-SHOW – VIC MENSA DANCER CHOREO: IAN EASTWOOD BET’S SPRING BLING W/TRIPL3 THREAT TRIPL3 THREAT CHOREO: SELF Music Videos PRINCE – “BREAKFAST CAN WAIT” CHOR/DANCER DIR: ROB WITT E40, CHRIS BROWN, TI – “EPISODE” CHOR/DANCER DIR: BEN GRIFFIN DRAKE – “THE MOTTO” DANCER DIR: LAMAR TAYLOR/HYGHLEY ALLEYNE PIA MIA - “MR. PRESIDENT” DANCER DIR: _P MAT KEARNEY – “HEARTBEAT” CHOREO DIR: WILLIAM RUSSEL Live/Stage Performances PRINCE ESSENCE FESTIVAL CHOR/DANCER SELF/NICOLE KIRKLAND CEELO GREEN EURO TOUR CHOR SELF MINDLESS BEHAVIOR AATW TOUR DANCER/CAPTAIN DAVE SCOTT MINDLESS BEHAVIOR #1 GIRL TOUR DANCER/CAPTAIN DAVE SCOTT/KOLANIE MARKS PIA MIA – GUAM LIVE DANCER FLII STYLZ ROSHON (SHAKE IT UP) DANCER ROSERO MCCOY SILLY WALKS FOR HUNGER DANCER CHOR: RICH + TONE DANCE CREW CANADA TOUR DANCER SUPREME SOUL AMERICAS BEST DANCE CREW TOUR OPENER CHOR/DANCER CHOR: SELF JESSICA SANCHEZ CHOR/DANCER CHOR: SELF LIL MAMA TEEN CHOICE AWARDS PARTY DANCER SUPREME SOUL NBA ALL-STARS WEEKEND – VEGAS CHOR/DANCER TRIPLE THREAT Commercials STARBUCKS FEATURED 72ANDSUNNY Training HIP HOP, KRUMP, POPPING, JAZZ, FREESTYLE, DEBBIE ALLEN, CHAPKIS DANCE STUDIO, MILLENIUM, IDA, MOVEMENT LIFESTYLE, DEBBIE REYNOLDS, ROBERT HOFFMAN, KOLANIE MARKS, GREG CHAPKIS, NICK WILSON, Special Skills (HIP HOP, JAZZ FUNK, KRUMP, POPPIN, FLEXING), DOUBLE JOINTED SHOULDERS, FOOTBALL, BASEBALL, BASKETBALL, TRACK, RECREATIONAL ACTIVITIES, BOWLING, ROLLERBLADING, SWIMMING, BIKING, BILLIARDS . -

Played 2013 IMOJP

Reverse Running Atoms For Peace AMOK XL Recordings Hittite Man The Fall Re-Mit Cherry Red Pre-Mdma Years The Fall Re-Mit Cherry Red Voodoo Posse Chronic Illusion Actress Silver Cloud WERKDISCS Recommended By Dentists Alex Dowling On The Nature Of ElectricityHeresy Records And Acoustics Smile (Pictures Or It Didn't Happen) Amanda Palmer & TheTheatre Grand Is EvilTheft OrchestraBandcamp Stoerung kiteki Rmx Antye Greie-Ripatti minimal tunesia Antye Greie-Ripatti nbi(AGF) 05 Line Ain't Got No Love Beal, Willis Earl Nobody knows. XL Recordings Marauder Black Pus All My Relations Thrill Jockey 1,000 Years Black Pus All My Relations Thrill Jockey Records All Out of Sorts Black Pus All My Relations Thrill Jockey Abstract Body/Head Coming Apart Matador Records Sintiendo Bomba Estéreo Elegancia Tropical Soundway #Colombia Amidinine Bombino Nomad Cumbancha Persistence Of Death Borut Krzisnik Krzisnik: Lightning Claudio Contemporary La noche mas larga Buika La noche mas largaWarner Music Spain Super Flumina Babylonis Caleb Burhans Evensong Cantaloupe Music Waiting For The Streetcar CAN The Lost Tapes [DiscMute 1] Obedience Carmen Villain Sleeper Smalltown Supersound Masters of the Internet Ceramic Dog Your Turn Northern-Spy Records track 2 Chris Silver T & MauroHigh Sambo Forest, LonelyOzky Feeling E-Sound Spectral Churches Coen Oscar PolackSpectral Churches Narrominded sundarbans coen oscar polack &fathomless herman wilken Narrominded To See More Light Colin Stetson New History WarfareConstellation Vol. 3: To See More Light The Neighborhood Darcy -

Jerry Garcia Song Book – Ver

JERRY GARCIA SONG BOOK – VER. 9 1. After Midnight 46. Chimes of Freedom 92. Freight Train 137. It Must Have Been The 2. Aiko-Aiko 47. blank page 93. Friend of the Devil Roses 3. Alabama Getaway 48. China Cat Sunflower 94. Georgia on My Mind 138. It Takes a lot to Laugh, It 4. All Along the 49. I Know You Rider 95. Get Back Takes a Train to Cry Watchtower 50. China Doll 96. Get Out of My Life 139. It's a Long, Long Way to 5. Alligator 51. Cold Rain and Snow 97. Gimme Some Lovin' the Top of the World 6. Althea 52. Comes A Time 98. Gloria 140. It's All Over Now 7. Amazing Grace 53. Corina 99. Goin' Down the Road 141. It's All Over Now Baby 8. And It Stoned Me 54. Cosmic Charlie Feelin' Bad Blue 9. Arkansas Traveler 55. Crazy Fingers 100. Golden Road 142. It's No Use 10. Around and Around 56. Crazy Love 101. Gomorrah 143. It's Too Late 11. Attics of My Life 57. Cumberland Blues 102. Gone Home 144. I've Been All Around This 12. Baba O’Riley --> 58. Dancing in the Streets 103. Good Lovin' World Tomorrow Never Knows 59. Dark Hollow 104. Good Morning Little 145. Jack-A-Roe 13. Ballad of a Thin Man 60. Dark Star Schoolgirl 146. Jack Straw 14. Beat it on Down The Line 61. Dawg’s Waltz 105. Good Time Blues 147. Jenny Jenkins 15. Believe It Or Not 62. Day Job 106. -

Wedding Ringer -FULL SCRIPT W GREEN REVISIONS.Pdf

THE WEDDING RINGER FKA BEST MAN, Inc. / THE GOLDEN TUX by Jeremy Garelick & Jay Lavender GREEN REVISED - 10.22.13 YELLOW REVISED - 10.11.13 PINK REVISED - 10.1.13 BLUE REVISED - 9.17.13 WHITE SHOOTING SCRIPT - 8.27.13 Screen Gems Productions, Inc. 10202 W. Washington Blvd. Stage 6 Suite 4100 Culver City, CA 90232 GREEN REVISED 10.22.13 1 OVER BLACK A DIAL TONE...numbers DIALED...phone RINGING. SETH (V.O.) Hello? DOUG (V.O.) Oh hi, uh, Seth? SETH (V.O.) Yeah? DOUG (V.O.) It’s Doug. SETH (V.O.) Doug? Doug who? OPEN TIGHT ON DOUG Doug Harris... 30ish, on the slightly dweebier side of average. 1 REVEAL: INT. DOUG’S OFFICE - DAY 1 Organized clutter, stacks of paper cover the desk. Vintage posters/jerseys of Los Angeles sports legends adorn the walls- -ERIC DICKERSON, JIM PLUNKETT, KURT RAMBIS, STEVE GARVEY- DOUG You know, Doug Harris...Persian Rug Doug? SETH (OVER PHONE) Doug Harris! Of course. What’s up? DOUG (relieved) I know it’s been awhile, but I was calling because, I uh, have some good news...I’m getting married. SETH (OVER PHONE) That’s great. Congratulations. DOUG And, well, I was wondering if you might be interested in perhaps being my best man. GREEN REVISED 10.22.13 2 Dead silence. SETH (OVER PHONE) I have to be honest, Doug. This is kind of awkward. I mean, we don’t really know each other that well. DOUG Well...what about that weekend in Carlsbad Caverns? SETH (OVER PHONE) That was a ninth grade field trip, the whole class went. -

JUST AFTER SUNSET Ebook Free Download

JUST AFTER SUNSET PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Stephen King | 539 pages | 04 Mar 2010 | Simon + Schuster Inc. | 9781439144916 | English | none JUST AFTER SUNSET PDF Book Terrible, in poor taste, I'm disgusted. Then they were both gone. He came upon a Budweiser can and kicked it awhile. Harvey's Dream-short but chilling.. Maybe her first name was Sally, but David thought he would have remembered a name like that; there were so few Sallys these days. Baby wants to dance. His shadow grew long, shortened in the glow of the hanging fluorescents, then grew long again. What we have here seems to be more like a collection of literary doodles or proof of concepts that just kind of fell out of King's brain. United States of America. And where, exactly, would she have gone looking for fun? N: A psychiatrist commits suicide and his sister reads the file on his last patient, an OCD man named N. The horror has the old school feel to it and is quite effective in places but not as a whole. It was a barn of a place—there had to be five hundred people whooping it up—but he had no concerns about finding Willa. Get A Copy. He dropped his eyes to his feet instead. I said yes immediately. It dealt a little with identity but was mostly a writer gathering up the courage to do something about a bad situation. Read those two lines at the bottom and then we can get this show on the road. It was red, white, and blue; in Wyoming, they did seem to love their red, white, and blue. -

Karaoke Mietsystem Songlist

Karaoke Mietsystem Songlist Ein Karaokesystem der Firma Showtronic Solutions AG in Zusammenarbeit mit Karafun. Karaoke-Katalog Update vom: 13/10/2020 Singen Sie online auf www.karafun.de Gesamter Katalog TOP 50 Shallow - A Star is Born Take Me Home, Country Roads - John Denver Skandal im Sperrbezirk - Spider Murphy Gang Griechischer Wein - Udo Jürgens Verdammt, Ich Lieb' Dich - Matthias Reim Dancing Queen - ABBA Dance Monkey - Tones and I Breaking Free - High School Musical In The Ghetto - Elvis Presley Angels - Robbie Williams Hulapalu - Andreas Gabalier Someone Like You - Adele 99 Luftballons - Nena Tage wie diese - Die Toten Hosen Ring of Fire - Johnny Cash Lemon Tree - Fool's Garden Ohne Dich (schlaf' ich heut' nacht nicht ein) - You Are the Reason - Calum Scott Perfect - Ed Sheeran Münchener Freiheit Stand by Me - Ben E. King Im Wagen Vor Mir - Henry Valentino And Uschi Let It Go - Idina Menzel Can You Feel The Love Tonight - The Lion King Atemlos durch die Nacht - Helene Fischer Roller - Apache 207 Someone You Loved - Lewis Capaldi I Want It That Way - Backstreet Boys Über Sieben Brücken Musst Du Gehn - Peter Maffay Summer Of '69 - Bryan Adams Cordula grün - Die Draufgänger Tequila - The Champs ...Baby One More Time - Britney Spears All of Me - John Legend Barbie Girl - Aqua Chasing Cars - Snow Patrol My Way - Frank Sinatra Hallelujah - Alexandra Burke Aber Bitte Mit Sahne - Udo Jürgens Bohemian Rhapsody - Queen Wannabe - Spice Girls Schrei nach Liebe - Die Ärzte Can't Help Falling In Love - Elvis Presley Country Roads - Hermes House Band Westerland - Die Ärzte Warum hast du nicht nein gesagt - Roland Kaiser Ich war noch niemals in New York - Ich War Noch Marmor, Stein Und Eisen Bricht - Drafi Deutscher Zombie - The Cranberries Niemals In New York Ich wollte nie erwachsen sein (Nessajas Lied) - Don't Stop Believing - Journey EXPLICIT Kann Texte enthalten, die nicht für Kinder und Jugendliche geeignet sind. -

The Composition of the Lunar Crust: Radiative Transfer Modeling and Analysis of Lunar Visible and Near-Infrared Spectra

THE COMPOSITION OF THE LUNAR CRUST: RADIATIVE TRANSFER MODELING AND ANALYSIS OF LUNAR VISIBLE AND NEAR-INFRARED SPECTRA A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI‘I IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN GEOLOGY AND GEOPHYSICS DECEMBER 2009 By Joshua T.S. Cahill Dissertation Committee: Paul G. Lucey, Chairperson G. Jeffrey Taylor Patricia Fryer Jeffrey J. Gillis-Davis Trevor Sorensen Student: Joshua T.S. Cahill Student ID#: 1565-1460 Field: Geology and Geophysics Graduation date: December 2009 Title: The Composition of the Lunar Crust: Radiative Transfer Modeling and Analysis of Lunar Visible and Near-Infrared Spectra We certify that we have read this dissertation and that, in our opinion, it is satisfactory in scope and quality as a dissertation for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Geology and Geophysics. Dissertation Committee: Names Signatures Paul G. Lucey, Chairperson ____________________________ G. Jeffrey Taylor ____________________________ Jeffrey J. Gillis-Davis ____________________________ Patricia Fryer ____________________________ Trevor Sorensen ____________________________ ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I must first express my love and appreciation to my family. Thank you to my wife Karen for providing love, support, and perspective. And to our little girl Maggie who only recently became part of our family and has already provided priceless memories in the form of beautiful smiles, belly laughs, and little bear hugs. The two of you provided me with the most meaningful reasons to push towards the "finish line". I would also like to thank my immediate and extended family. Many of them do not fully understand much about what I do, but support the endeavor acknowledging that if it is something I’m willing to put this much effort into, it must be worthwhile. -

OSAA Boys Track & Field Championships

OSAA Boys Track & Field Championships 4A Individual State Champions Through 2006 100-METER DASH 1992 Seth Wetzel, Jesuit ............................................ 1:53.20 1978 Byron Howell, Central Catholic................................. 10.5 1993 Jon Ryan, Crook County ..................................... 1:52.44 300-METER INTERMEDIATE HURDLES 1979 Byron Howell, Central Catholic............................... 10.67 1994 Jon Ryan, Crook County ..................................... 1:54.93 1978 Rourke Lowe, Aloha .............................................. 38.01 1980 Byron Howell, Central Catholic............................... 10.64 1995 Bryan Berryhill, Crater ....................................... 1:53.95 1979 Ken Scott, Aloha .................................................. 36.10 1981 Kevin Vixie, South Eugene .................................... 10.89 1996 Bryan Berryhill, Crater ....................................... 1:56.03 1980 Jerry Abdie, Sunset ................................................ 37.7 1982 Kevin Vixie, South Eugene .................................... 10.64 1997 Rob Vermillion, Glencoe ..................................... 1:55.49 1981 Romund Howard, Madison ....................................... 37.3 1983 John Frazier, Jefferson ........................................ 10.80w 1998 Tim Meador, South Medford ............................... 1:55.21 1982 John Elston, Lebanon ............................................ 39.02 1984 Gus Envela, McKay............................................. 10.55w 1999 -

Stephen-King-Book-List

BOOK NERD ALERT: STEPHEN KING ULTIMATE BOOK SELECTIONS *Short stories and poems on separate pages Stand-Alone Novels Carrie Salem’s Lot Night Shift The Stand The Dead Zone Firestarter Cujo The Plant Christine Pet Sematary Cycle of the Werewolf The Eyes Of The Dragon The Plant It The Eyes of the Dragon Misery The Tommyknockers The Dark Half Dolan’s Cadillac Needful Things Gerald’s Game Dolores Claiborne Insomnia Rose Madder Umney’s Last Case Desperation Bag of Bones The Girl Who Loved Tom Gordon The New Lieutenant’s Rap Blood and Smoke Dreamcatcher From a Buick 8 The Colorado Kid Cell Lisey’s Story Duma Key www.booknerdalert.com Last updated: 7/15/2020 Just After Sunset The Little Sisters of Eluria Under the Dome Blockade Billy 11/22/63 Joyland The Dark Man Revival Sleeping Beauties w/ Owen King The Outsider Flight or Fright Elevation The Institute Later Written by his penname Richard Bachman: Rage The Long Walk Blaze The Regulators Thinner The Running Man Roadwork Shining Books: The Shining Doctor Sleep Green Mile The Two Dead Girls The Mouse on the Mile Coffey’s Heads The Bad Death of Eduard Delacroix Night Journey Coffey on the Mile The Dark Tower Books The Gunslinger The Drawing of the Three The Waste Lands Wizard and Glass www.booknerdalert.com Last updated: 7/15/2020 Wolves and the Calla Song of Susannah The Dark Tower The Wind Through the Keyhole Talisman Books The Talisman Black House Bill Hodges Trilogy Mr. Mercedes Finders Keepers End of Watch Short