Report on Carcinogens, Fourteenth Edition for Table of Contents, See Home Page

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Effect of Insulations on Cop in Vapor Compression Refrigeration System

International Journal of Mechanical Engineering and Technology (IJMET) Volume 10, Issue 01, January 2019, pp. 1201-1208, Article ID: IJMET_10_01_122 Available online at http://www.iaeme.com/ijmet/issues.asp?JType=IJMET&VType=10&IType= 01 ISSN Print: 0976-6340 and ISSN Online: 0976-6359 © IAEME Publication Scopus Indexed EFFECT OF INSULATIONS ON COP IN VAPOR COMPRESSION REFRIGERATION SYSTEM Anusha Peyyala Assistant Professor P V P Siddhartha Institute of Technology, Research Scholar, Acharya Nagarjuna University, India. Dr N V V S Sudheer Associate Professor, R V R & J C College of Engineering, Guntur India ABSTRACT In this project, experimentation is done on Vapour Compression Refrigeration System [VCRS] as the COP is high for this system and it is the present trend of the HVAC in the domestic industry. This study presents investigation of best suited refrigerant and insulation combination for gas pipeline and liquid pipeline of a split air conditioning system. Analysis are performed for R22-Chlorodiflouromethane, a HydroChloroFlouro Carbon refrigerant, which has been using in the present world that cause both global warming and ozone layer depletion and R410a, mixture of di- flouromethane and pentaflouroethane, a Hydroflouro carbon refrigerant, which is future of HVAC which reduces the effect of ozone layer depletion [ODP] and Global Warming Potential [GWP].For these two refrigerants, we had found out the best insulation suitable as insulation also affects the COP of air conditioner, which has been observed from the literature. Minimizing the temperature of refrigerant in suction line helps condensing unit work more effectively intern the system performance increases. This reduces the overall power required for working of air conditioner, thereby reducing the maintenance cost of system. -

Precursors and Chemicals Frequently Used in the Illicit Manufacture of Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic Substances 2017

INTERNATIONAL NARCOTICS CONTROL BOARD Precursors and chemicals frequently used in the illicit manufacture of narcotic drugs and psychotropic substances 2017 EMBARGO Observe release date: Not to be published or broadcast before Thursday, 1 March 2018, at 1100 hours (CET) UNITED NATIONS CAUTION Reports published by the International Narcotics Control Board in 2017 The Report of the International Narcotics Control Board for 2017 (E/INCB/2017/1) is supplemented by the following reports: Narcotic Drugs: Estimated World Requirements for 2018—Statistics for 2016 (E/INCB/2017/2) Psychotropic Substances: Statistics for 2016—Assessments of Annual Medical and Scientific Requirements for Substances in Schedules II, III and IV of the Convention on Psychotropic Substances of 1971 (E/INCB/2017/3) Precursors and Chemicals Frequently Used in the Illicit Manufacture of Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic Substances: Report of the International Narcotics Control Board for 2017 on the Implementation of Article 12 of the United Nations Convention against Illicit Traffic in Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic Substances of 1988 (E/INCB/2017/4) The updated lists of substances under international control, comprising narcotic drugs, psychotropic substances and substances frequently used in the illicit manufacture of narcotic drugs and psychotropic substances, are contained in the latest editions of the annexes to the statistical forms (“Yellow List”, “Green List” and “Red List”), which are also issued by the Board. Contacting the International Narcotics Control Board The secretariat of the Board may be reached at the following address: Vienna International Centre Room E-1339 P.O. Box 500 1400 Vienna Austria In addition, the following may be used to contact the secretariat: Telephone: (+43-1) 26060 Fax: (+43-1) 26060-5867 or 26060-5868 Email: [email protected] The text of the present report is also available on the website of the Board (www.incb.org). -

New and Improved Infrared Absorption Cross Sections for Chlorodifluoromethane (HCFC-22)

Atmos. Meas. Tech., 9, 2593–2601, 2016 www.atmos-meas-tech.net/9/2593/2016/ doi:10.5194/amt-9-2593-2016 © Author(s) 2016. CC Attribution 3.0 License. New and improved infrared absorption cross sections for chlorodifluoromethane (HCFC-22) Jeremy J. Harrison1,2 1Department of Physics and Astronomy, University of Leicester, University Road, Leicester, LE1 7RH, UK 2National Centre for Earth Observation, University of Leicester, University Road, Leicester, LE1 7RH, UK Correspondence to: Jeremy J. Harrison ([email protected]) Received: 10 December 2015 – Published in Atmos. Meas. Tech. Discuss.: 18 January 2016 Revised: 3 May 2016 – Accepted: 6 May 2016 – Published: 17 June 2016 Abstract. The most widely used hydrochlorofluorocarbon 1 Introduction (HCFC) commercially since the 1930s has been chloro- difluoromethane, or HCFC-22, which has the undesirable The consumer appetite for safe household refrigeration led effect of depleting stratospheric ozone. As this molecule to the commercialisation in the 1930s of dichlorodifluo- is currently being phased out under the Montreal Pro- romethane, or CFC-12, a non-flammable and non-toxic re- tocol, monitoring its concentration profiles using infrared frigerant (Myers, 2007). Within the next few decades, other sounders crucially requires accurate laboratory spectroscopic chemically related refrigerants were additionally commer- data. This work describes new high-resolution infrared ab- cialised, including chlorodifluoromethane, or a hydrochlo- sorption cross sections of chlorodifluoromethane over the rofluorocarbon known as HCFC-22, which found use in a spectral range 730–1380 cm−1, determined from spectra wide array of applications such as air conditioners, chillers, recorded using a high-resolution Fourier transform spectrom- and refrigeration for food retail and industrial processes. -

A Van Der Waals Density Functional Study of Chloroform and Other Trihalomethanes on Graphene Joel Åkesson, Oskar Sundborg, Olof Wahlström, and Elsebeth Schröder

A van der Waals density functional study of chloroform and other trihalomethanes on graphene Joel Åkesson, Oskar Sundborg, Olof Wahlström, and Elsebeth Schröder Citation: J. Chem. Phys. 137, 174702 (2012); doi: 10.1063/1.4764356 View online: http://dx.doi.org/10.1063/1.4764356 View Table of Contents: http://jcp.aip.org/resource/1/JCPSA6/v137/i17 Published by the American Institute of Physics. Additional information on J. Chem. Phys. Journal Homepage: http://jcp.aip.org/ Journal Information: http://jcp.aip.org/about/about_the_journal Top downloads: http://jcp.aip.org/features/most_downloaded Information for Authors: http://jcp.aip.org/authors THE JOURNAL OF CHEMICAL PHYSICS 137, 174702 (2012) A van der Waals density functional study of chloroform and other trihalomethanes on graphene Joel Åkesson,1 Oskar Sundborg,1 Olof Wahlström,1 and Elsebeth Schröder2,a) 1Hulebäcksgymnasiet, Idrottsvägen 2, SE-435 80 Mölnlycke, Sweden 2Microtechnology and Nanoscience, MC2, Chalmers University of Technology, SE-412 96 Göteborg, Sweden (Received 25 July 2012; accepted 14 October 2012; published online 1 November 2012) A computational study of chloroform (CHCl3) and other trihalomethanes (THMs) adsorbed on graphene is presented. The study uses the van der Waals density functional method to obtain ad- sorption energies and adsorption structures for these molecules of environmental concern. In this study, chloroform is found to adsorb with the H atom pointing away from graphene, with adsorption energy 357 meV (34.4 kJ/mol). For the other THMs studied the calculated adsorption energy values vary from 206 meV (19.9 kJ/mol) for fluoroform (CHF3) to 404 meV (39.0 kJ/mol) for bromoform (CHBr3). -

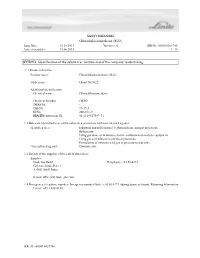

SAFETY DATA SHEET Chlorodifluoromethane (R 22) Issue Date: 16.01.2013 Version: 1.0 SDS No.: 000010021746 Last Revised Date: 18.06.2015 1/15

SAFETY DATA SHEET Chlorodifluoromethane (R 22) Issue Date: 16.01.2013 Version: 1.0 SDS No.: 000010021746 Last revised date: 18.06.2015 1/15 SECTION 1: Identification of the substance/mixture and of the company/undertaking 1.1 Product identifier Product name: Chlorodifluoromethane (R 22) Trade name: Gasart 503 R22 Additional identification Chemical name: Chlorodifluoromethane Chemical formula: CHClF2 INDEX No. - CAS-No. 75-45-6 EC No. 200-871-9 REACH Registration No. 01-2119517587-31 1.2 Relevant identified uses of the substance or mixture and uses advised against Identified uses: Industrial and professional. Perform risk assessment prior to use. Refrigerant. Using gas alone or in mixtures for the calibration of analysis equipment. Using gas as feedstock in chemical processes. Formulation of mixtures with gas in pressure receptacles. Uses advised against Consumer use. 1.3 Details of the supplier of the safety data sheet Supplier Linde Gas GmbH Telephone: +43 50 4273 Carl-von-Linde-Platz 1 A-4651 Stadl-Paura E-mail: [email protected] 1.4 Emergency telephone number: Emergency number Linde: + 43 50 4273 (during business hours), Poisoning Information Center: +43 1 406 43 43 SDS_AT - 000010021746 SAFETY DATA SHEET Chlorodifluoromethane (R 22) Issue Date: 16.01.2013 Version: 1.0 SDS No.: 000010021746 Last revised date: 18.06.2015 2/15 SECTION 2: Hazards identification 2.1 Classification of the substance or mixture Classification according to Directive 67/548/EEC or 1999/45/EC as amended. N; R59 The full text for all R-phrases is displayed in section 16. Classification according to Regulation (EC) No 1272/2008 as amended. -

UNITED STATES PATENT of FICE 2,640,086 PROCESS for SEPARATING HYDROGEN FLUORIDE from CHLORODFLUORO METHANE Robert H

Patented May 26, 1953 2,640,086 UNITED STATES PATENT of FICE 2,640,086 PROCESS FOR SEPARATING HYDROGEN FLUORIDE FROM CHLORODFLUORO METHANE Robert H. Baldwin, Chadds Ford, Pa., assignor to E. H. du Pont de Nemours and Company, Wi inington, Del, a corporation of Delaware No Drawing. Application December 15, 1951, Serial No. 261,929 9 Claims. (C. 260-653) 2 This invention relates to a process for Sep These objects are accomplished essentially by arating hydrogen fluoride from monochlorodi Subjecting a mixture of hydrogen fluoride and fluoronethane, and more particularly, separat Inonochlorodifluoromethane in the liquid phase ing these components from the reaction mixture to temperatures below 0° C., preferably at about obtained in the fluorination of chloroform with -30° C. to -50° C., at either atmospheric or hydrogen fluoride, Super-atmospheric pressures, together with from In the fluorination of chloroform in the prest about 0.25 mol to about 2.5 mols of chloroform ence Of a Catalyst, a reaction mixture is pro per mol of chlorodifluoronethane contained in duced which consists essentially of HCl, HF, the mixture and separating an upper layer rich CHCIF2, CHCl2F, CHCls, and CHF3. A method O in HF from a lower organic layer. The proceSS of Separating these components is disclosed in is operative with mixtures containing up to 77% U. S. Patent No. 2,450,414 which involves sep by weight of HF. arating the components by a special fractional It has been found that chloroform is substan distillation under appropriate temperatures and tially immiscible With EIF at temperatures be pressures. -

Pharmacy and Poisons (Third and Fourth Schedule Amendment) Order 2017

Q UO N T FA R U T A F E BERMUDA PHARMACY AND POISONS (THIRD AND FOURTH SCHEDULE AMENDMENT) ORDER 2017 BR 111 / 2017 The Minister responsible for health, in exercise of the power conferred by section 48A(1) of the Pharmacy and Poisons Act 1979, makes the following Order: Citation 1 This Order may be cited as the Pharmacy and Poisons (Third and Fourth Schedule Amendment) Order 2017. Repeals and replaces the Third and Fourth Schedule of the Pharmacy and Poisons Act 1979 2 The Third and Fourth Schedules to the Pharmacy and Poisons Act 1979 are repealed and replaced with— “THIRD SCHEDULE (Sections 25(6); 27(1))) DRUGS OBTAINABLE ONLY ON PRESCRIPTION EXCEPT WHERE SPECIFIED IN THE FOURTH SCHEDULE (PART I AND PART II) Note: The following annotations used in this Schedule have the following meanings: md (maximum dose) i.e. the maximum quantity of the substance contained in the amount of a medicinal product which is recommended to be taken or administered at any one time. 1 PHARMACY AND POISONS (THIRD AND FOURTH SCHEDULE AMENDMENT) ORDER 2017 mdd (maximum daily dose) i.e. the maximum quantity of the substance that is contained in the amount of a medicinal product which is recommended to be taken or administered in any period of 24 hours. mg milligram ms (maximum strength) i.e. either or, if so specified, both of the following: (a) the maximum quantity of the substance by weight or volume that is contained in the dosage unit of a medicinal product; or (b) the maximum percentage of the substance contained in a medicinal product calculated in terms of w/w, w/v, v/w, or v/v, as appropriate. -

Use of Chlorofluorocarbons in Hydrology : a Guidebook

USE OF CHLOROFLUOROCARBONS IN HYDROLOGY A Guidebook USE OF CHLOROFLUOROCARBONS IN HYDROLOGY A GUIDEBOOK 2005 Edition The following States are Members of the International Atomic Energy Agency: AFGHANISTAN GREECE PANAMA ALBANIA GUATEMALA PARAGUAY ALGERIA HAITI PERU ANGOLA HOLY SEE PHILIPPINES ARGENTINA HONDURAS POLAND ARMENIA HUNGARY PORTUGAL AUSTRALIA ICELAND QATAR AUSTRIA INDIA REPUBLIC OF MOLDOVA AZERBAIJAN INDONESIA ROMANIA BANGLADESH IRAN, ISLAMIC REPUBLIC OF RUSSIAN FEDERATION BELARUS IRAQ SAUDI ARABIA BELGIUM IRELAND SENEGAL BENIN ISRAEL SERBIA AND MONTENEGRO BOLIVIA ITALY SEYCHELLES BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA JAMAICA SIERRA LEONE BOTSWANA JAPAN BRAZIL JORDAN SINGAPORE BULGARIA KAZAKHSTAN SLOVAKIA BURKINA FASO KENYA SLOVENIA CAMEROON KOREA, REPUBLIC OF SOUTH AFRICA CANADA KUWAIT SPAIN CENTRAL AFRICAN KYRGYZSTAN SRI LANKA REPUBLIC LATVIA SUDAN CHAD LEBANON SWEDEN CHILE LIBERIA SWITZERLAND CHINA LIBYAN ARAB JAMAHIRIYA SYRIAN ARAB REPUBLIC COLOMBIA LIECHTENSTEIN TAJIKISTAN COSTA RICA LITHUANIA THAILAND CÔTE D’IVOIRE LUXEMBOURG THE FORMER YUGOSLAV CROATIA MADAGASCAR REPUBLIC OF MACEDONIA CUBA MALAYSIA TUNISIA CYPRUS MALI TURKEY CZECH REPUBLIC MALTA UGANDA DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC MARSHALL ISLANDS UKRAINE OF THE CONGO MAURITANIA UNITED ARAB EMIRATES DENMARK MAURITIUS UNITED KINGDOM OF DOMINICAN REPUBLIC MEXICO GREAT BRITAIN AND ECUADOR MONACO NORTHERN IRELAND EGYPT MONGOLIA UNITED REPUBLIC EL SALVADOR MOROCCO ERITREA MYANMAR OF TANZANIA ESTONIA NAMIBIA UNITED STATES OF AMERICA ETHIOPIA NETHERLANDS URUGUAY FINLAND NEW ZEALAND UZBEKISTAN FRANCE NICARAGUA VENEZUELA GABON NIGER VIETNAM GEORGIA NIGERIA YEMEN GERMANY NORWAY ZAMBIA GHANA PAKISTAN ZIMBABWE The Agency’s Statute was approved on 23 October 1956 by the Conference on the Statute of the IAEA held at United Nations Headquarters, New York; it entered into force on 29 July 1957. The Headquarters of the Agency are situated in Vienna. -

CYCLE D-HX: NIST Vapor Compression Cycle Model Accounting for Refrigerant Thermodynamic and Transport Properties

NIST Technical Note 1974 CYCLE_D-HX: NIST Vapor Compression Cycle Model Accounting for Refrigerant Thermodynamic and Transport Properties Version 1.0 User’s Guide J.S. Brown R. Brignoli P.A. Domanski This publication is available free of charge from: https://doi.org/10.6028/NIST.TN.1974 NIST Technical Note 1974 CYCLE_D-HX: NIST Vapor Compression Cycle Model Accounting for Refrigerant Thermodynamic and Transport Properties Version 1.0 User’s Guide J.S. Brown The Catholic University of America R. Brignoli P.A. Domanski Engineering Laboratory National Institute of Standards and Technology This publication is available free of charge from: https://doi.org/10.6028/NIST.TN.1974 December 2017 U.S. Department of Commerce Wilbur L. Ross, Jr., Secretary National Institute of Standards and Technology Walter Copan, NIST Director and Under Secretary of Commerce for Standards and Technology This software package was developed by the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST), is not subject to copyright protection, and is in the public domain. It can be used freely provided that any derivative works bear some notice that they are derived from it. NIST used its best efforts to provide a high-quality software package and to select modeling methods and correlations based on sound scientific judgement. However, NIST assumes neither responsibility nor liability for any damage arising out of or relating to the use of CYCLE_D-HX. The software is provided “AS IS”; NIST makes NO GUARANTIES and NO WARRANTIES OF ANY TYPE, expressed or implied, including NO WARRANTY OF MERCHANTABILITY OR FITNESS FOR A PARTICULAR PURPOSE. -

The Effects of the Morphine Analogue Levorphanol on Leukocytes: Metabolic Effects at Rest and During Phagocytosis

The effects of the morphine analogue levorphanol on leukocytes: Metabolic effects at rest and during phagocytosis Nancy Wurster, … , Penelope Pettis, Sharon Lebow J Clin Invest. 1971;50(5):1091-1099. https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI106580. Studies on bacteria have suggested that morphine-like drugs have effects on the cell membrane. To determine the effect of this class of drugs on a mammalian cell, we selected the rabbit peritoneal exudate granulocyte, which undergoes striking membrane changes during phagocytosis. We examined the effect in vitro of the morphine analogue, levorphanol on phagocytosis and metabolism by granulocytes incubated with and without polystyrene particles or live Escherichia coli. Levorphanol (1 or 2 mmoles/liter) decreased: (a) acylation of lysolecithin or lysophosphatidylethanolamine in the medium (which is stimulated about two-fold during phagocytosis) both at rest (40%) and during phagocytosis (60%); (b) uptake of latex particles and Escherichia coli, as judged by electron microscopy; (c) killing of live Escherichia coli (10-fold); (d) 14 14 + CO2 production from glucose-1- C during phagocytosis by at least 80%; (e) K content of granulocytes (35%); (f) oxidation of linoleate-1-14C by 50%, and its incorporation into triglyceride by more than 80%. However, levorphanol stimulated 2 to 3-fold the incorporation of linoleate-1-14C or palmitate-1-14C into several phospholipids. Glucose uptake, lactate production, and adenosine triphosphate (ATP) content are not affected by the drug. Thus, levorphanol does not appear to exert its effects through generalized metabolic suppression. Removal of levorphanol by twice resuspending the granulocytes completely reverses all inhibition. In line with observations on bacteria, it appears that the complex effects of levorphanol on […] Find the latest version: https://jci.me/106580/pdf The Effects of the Morphine Analogue Levorphanol on Leukocytes METABOLIC EFFECTS AT REST AND DURING PHAGOCYTOSIS NANcY WuRsTE, PETER ELSBACH, ERIc J. -

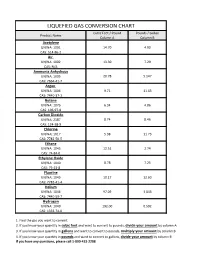

Liquefied Gas Conversion Chart

LIQUEFIED GAS CONVERSION CHART Cubic Feet / Pound Pounds / Gallon Product Name Column A Column B Acetylene UN/NA: 1001 14.70 4.90 CAS: 514-86-2 Air UN/NA: 1002 13.30 7.29 CAS: N/A Ammonia Anhydrous UN/NA: 1005 20.78 5.147 CAS: 7664-41-7 Argon UN/NA: 1006 9.71 11.63 CAS: 7440-37-1 Butane UN/NA: 1075 6.34 4.86 CAS: 106-97-8 Carbon Dioxide UN/NA: 2187 8.74 8.46 CAS: 124-38-9 Chlorine UN/NA: 1017 5.38 11.73 CAS: 7782-50-5 Ethane UN/NA: 1045 12.51 2.74 CAS: 74-84-0 Ethylene Oxide UN/NA: 1040 8.78 7.25 CAS: 75-21-8 Fluorine UN/NA: 1045 10.17 12.60 CAS: 7782-41-4 Helium UN/NA: 1046 97.09 1.043 CAS: 7440-59-7 Hydrogen UN/NA: 1049 192.00 0.592 CAS: 1333-74-0 1. Find the gas you want to convert. 2. If you know your quantity in cubic feet and want to convert to pounds, divide your amount by column A 3. If you know your quantity in gallons and want to convert to pounds, multiply your amount by column B 4. If you know your quantity in pounds and want to convert to gallons, divide your amount by column B If you have any questions, please call 1-800-433-2288 LIQUEFIED GAS CONVERSION CHART Cubic Feet / Pound Pounds / Gallon Product Name Column A Column B Hydrogen Chloride UN/NA: 1050 10.60 8.35 CAS: 7647-01-0 Krypton UN/NA: 1056 4.60 20.15 CAS: 7439-90-9 Methane UN/NA: 1971 23.61 3.55 CAS: 74-82-8 Methyl Bromide UN/NA: 1062 4.03 5.37 CAS: 74-83-9 Neon UN/NA: 1065 19.18 10.07 CAS: 7440-01-9 Mapp Gas UN/NA: 1060 9.20 4.80 CAS: N/A Nitrogen UN/NA: 1066 13.89 6.75 CAS: 7727-37-9 Nitrous Oxide UN/NA: 1070 8.73 6.45 CAS: 10024-97-2 Oxygen UN/NA: 1072 12.05 9.52 CAS: 7782-44-7 Propane UN/NA: 1075 8.45 4.22 CAS: 74-98-6 Sulfur Dioxide UN/NA: 1079 5.94 12.0 CAS: 7446-09-5 Xenon UN/NA: 2036 2.93 25.51 CAS: 7440-63-3 1. -

Reducing Trihalomethane Concentrations by Using Chloramines As a Disinfectant

REDUCING TRIHALOMETHANE CONCENTRATIONS BY USING CHLORAMINES AS A DISINFECTANT by Elizabeth Anne Farren A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the WORCESTER POLYTECHNIC INSTITUTE in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Environmental Engineering by ___________________________________ April 2003 APPROVED: ___________________________________ Dr. Jeanine D. Plummer, Major Advisor ____________________________________ Dr. Frederick L. Hart, Head of Department Abstract Disinfectants such as chlorine are used in drinking water treatment to protect the public health from pathogenic microorganisms. However, disinfectants also react with humic material present in raw water sources and produce by-products, such as trihalomethanes. Total trihalomethanes (TTHMs) include four compounds: chloroform, bromodichloromethane, dibromochloromethane and bromoform. TTHMs are carcinogenic and have been found to cause adverse pregnancy outcomes. Therefore, the United States Environmental Protection Agency (U.S. EPA) has set the maximum contaminant limit for TTHMs at 80 µg/L. Additional regulations require reliable drinking water disinfection for resistant pathogens and treatment plants must simultaneously control TTHMs and achieve proper disinfection. Research has shown that THM formation depends on several factors. THM concentrations increase with increasing residence time, increased temperature and increased pH. The disinfectant type and concentration is also significant: THM concentrations can be minimized by using lower disinfectant doses or alternative disinfectants to chlorine such as chloramines. Chloramines are formed by the addition of both chlorine and ammonia. The Worcester Water Filtration Plant in Holden, MA currently uses both ozone and chlorine for primary disinfection. Chlorine is also used for secondary disinfection. This study analyzed the effect of using chloramines versus free chlorine on TTHM production at the plant.