Regional Overview Multilateral Solutions to Bilateral Problems Help Contain Unilateralist Tendencies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Congressional Record—Senate S3730

S3730 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — SENATE June 12, 2018 I know each of my colleagues can tes- On Christmas Eve last year, the sen- gressional review of certain regulations tify to the important roles military in- ior Senator from Montana took to the issued by the Committee on Foreign Invest- stallations play in communities all Bozeman Daily Chronicle with a piece ment in the United States. across our country. My fellow Ken- titled ‘‘Tax bill a disastrous plan, fails Reed/Warren amendment No. 2756 (to amendment No. 2700), to require the author- tuckians and I take great pride in Fort Montana and our future.’’ Quite a pro- ization of appropriation of amounts for the Campbell, Fort Knox, and the Blue nouncement. It reminded me of the development of new or modified nuclear Grass Army Depot. We are proud that Democratic leader of the House. She weapons. Kentucky is home base to many out- said our plan to give tax cuts to mid- Lee amendment No. 2366 (to the language standing units, such as the 101st Air- dle-class families and businesses would proposed to be stricken by amendment No. borne Division and those of Kentucky’s bring about ‘‘Armageddon.’’ Armaged- 2282), to clarify that an authorization to use Air and Army National Guard units. don. military force, a declaration of war, or any In our State, as in every State, the How are these prognostications hold- similar authority does not authorize the de- tention without charge or trial of a citizen military’s presence anchors entire ing up? The new Tax Code is causing or lawful permanent resident of the United communities and offers a constant re- Northwestern Energy to pass along States. -

Annual Report

COUNCIL ON FOREIGN RELATIONS ANNUAL REPORT July 1,1996-June 30,1997 Main Office Washington Office The Harold Pratt House 1779 Massachusetts Avenue, N.W. 58 East 68th Street, New York, NY 10021 Washington, DC 20036 Tel. (212) 434-9400; Fax (212) 861-1789 Tel. (202) 518-3400; Fax (202) 986-2984 Website www. foreignrela tions. org e-mail publicaffairs@email. cfr. org OFFICERS AND DIRECTORS, 1997-98 Officers Directors Charlayne Hunter-Gault Peter G. Peterson Term Expiring 1998 Frank Savage* Chairman of the Board Peggy Dulany Laura D'Andrea Tyson Maurice R. Greenberg Robert F Erburu Leslie H. Gelb Vice Chairman Karen Elliott House ex officio Leslie H. Gelb Joshua Lederberg President Vincent A. Mai Honorary Officers Michael P Peters Garrick Utley and Directors Emeriti Senior Vice President Term Expiring 1999 Douglas Dillon and Chief Operating Officer Carla A. Hills Caryl R Haskins Alton Frye Robert D. Hormats Grayson Kirk Senior Vice President William J. McDonough Charles McC. Mathias, Jr. Paula J. Dobriansky Theodore C. Sorensen James A. Perkins Vice President, Washington Program George Soros David Rockefeller Gary C. Hufbauer Paul A. Volcker Honorary Chairman Vice President, Director of Studies Robert A. Scalapino Term Expiring 2000 David Kellogg Cyrus R. Vance Jessica R Einhorn Vice President, Communications Glenn E. Watts and Corporate Affairs Louis V Gerstner, Jr. Abraham F. Lowenthal Hanna Holborn Gray Vice President and Maurice R. Greenberg Deputy National Director George J. Mitchell Janice L. Murray Warren B. Rudman Vice President and Treasurer Term Expiring 2001 Karen M. Sughrue Lee Cullum Vice President, Programs Mario L. Baeza and Media Projects Thomas R. -

Strangers at Home: North Koreans in the South

STRANGERS AT HOME: NORTH KOREANS IN THE SOUTH Asia Report N°208 – 14 July 2011 TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ...................................................................................................... i I. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................. 1 II. CHANGING POLICIES TOWARDS DEFECTORS ................................................... 2 III. LESSONS FROM KOREAN HISTORY ........................................................................ 5 A. COLD WAR USES AND ABUSES .................................................................................................... 5 B. CHANGING GOVERNMENT ATTITUDES ......................................................................................... 8 C. A CHANGING NATION .................................................................................................................. 9 IV. THE PROBLEMS DEFECTORS FACE ...................................................................... 11 A. HEALTH ..................................................................................................................................... 11 1. Mental health ............................................................................................................................. 11 2. Physical health ........................................................................................................................... 12 B. LIVELIHOODS ............................................................................................................................ -

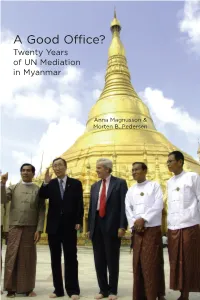

A Good Office? Twenty Years of UN Mediation in Myanmar

A Good Office? Twenty Years of UN Mediation in Myanmar Anna Magnusson & Morten B. Pedersen A Good Office? Twenty Years of UN Mediation in Myanmar Anna Magnusson and Morten B. Pedersen International Peace Institute, 777 United Nations Plaza, New York, NY 10017 www.ipinst.org © 2012 by International Peace Institute All rights reserved. Published 2012. Cover Photo: UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon, 2nd left, and UN Undersecretary-General for Humanitarian Affairs John Holmes, center, pose for a group photograph with Myanmar Foreign Minister Nyan Win, left, and two other unidentified Myanmar officials at Shwedagon Pagoda in Yangon, Myanmar, May 22, 2008 (AP Photo). Disclaimer: The views expressed in this publication represent those of the authors and not necessarily those of IPI. IPI welcomes consideration of a wide range of perspectives in the pursuit of a well-informed debate on critical policies and issues in international affairs. The International Peace Institute (IPI) is an independent, interna - tional institution dedicated to promoting the prevention and settle - ment of conflicts between and within states through policy research and development. IPI owes a debt of thanks to its many generous donors, including the governments of Norway and Finland, whose contributions make publications like this one possible. In particular, IPI would like to thank the government of Sweden and the Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency (SIDA) for their support of this project. ISBN: 0-937722-87-1 ISBN-13: 978-0-937722-87-9 CONTENTS Acknowledgements . v Acronyms . vii Introduction . 1 1. The Beginning of a Very Long Engagement (1990 –1994) Strengthening the Hand of the Opposition . -

Prologue This Report Is Submitted Pursuant to the ―United Nations Participation Act of 1945‖ (Public Law 79-264)

Prologue This report is submitted pursuant to the ―United Nations Participation Act of 1945‖ (Public Law 79-264). Section 4 of this law provides, in part, that: ―The President shall from time to time as occasion may require, but not less than once each year, make reports to the Congress of the activities of the United Nations and of the participation of the United States therein.‖ In July 2003, the President delegated to the Secretary of State the authority to transmit this report to Congress. The United States Participation in the United Nations report is a survey of the activities of the U.S. Government in the United Nations and its agencies, as well as the activities of the United Nations and those agencies themselves. More specifically, this report seeks to assess UN achievements during 2007, the effectiveness of U.S. participation in the United Nations, and whether U.S. goals were advanced or thwarted. The United States is committed to the founding ideals of the United Nations. Addressing the UN General Assembly in 2007, President Bush said: ―With the commitment and courage of this chamber, we can build a world where people are free to speak, assemble, and worship as they wish; a world where children in every nation grow up healthy, get a decent education, and look to the future with hope; a world where opportunity crosses every border. America will lead toward this vision where all are created equal, and free to pursue their dreams. This is the founding conviction of my country. It is the promise that established this body. -

Flags and Banners

Flags and Banners A Wikipedia Compilation by Michael A. Linton Contents 1 Flag 1 1.1 History ................................................. 2 1.2 National flags ............................................. 4 1.2.1 Civil flags ........................................... 8 1.2.2 War flags ........................................... 8 1.2.3 International flags ....................................... 8 1.3 At sea ................................................. 8 1.4 Shapes and designs .......................................... 9 1.4.1 Vertical flags ......................................... 12 1.5 Religious flags ............................................. 13 1.6 Linguistic flags ............................................. 13 1.7 In sports ................................................ 16 1.8 Diplomatic flags ............................................ 18 1.9 In politics ............................................... 18 1.10 Vehicle flags .............................................. 18 1.11 Swimming flags ............................................ 19 1.12 Railway flags .............................................. 20 1.13 Flagpoles ............................................... 21 1.13.1 Record heights ........................................ 21 1.13.2 Design ............................................. 21 1.14 Hoisting the flag ............................................ 21 1.15 Flags and communication ....................................... 21 1.16 Flapping ................................................ 23 1.17 See also ............................................... -

A Tour of the Largest Film Studio in North Korea Gives Kate Whitehead Some Insights Into the Propaganda Machine

6 FILM Seeing and believing he guide charged with second world war, on the site of a and offered plenty of “on-the-spot A tour of the showing visitors around the small sock factory 16 kilometres guidance”, a key feature of his largest film Korean Film Studio has the north of the capital. legacy. Much is made of Kim Jong- chiselled good looks of Taking heed from the Russian il’s love of films, but it should be The 55-days theory Tsomeone made for the big screen. example, the impact and use of remembered that this was also his studio in North His face remains deadpan as he propaganda was understood early in job: in 1970 he was appointed [and] other advice watches 20 foreigners emerge from North Korea and, despite a limited deputy director in charge of culture Korea gives the tour bus, all looking a little budget, the studios succeeded in and arts in the Propaganda and on filmmaking bedraggled at the end of the day. rolling out a number of feature films Guidance Department by his father, is laid out in Kate Whitehead He leads our Koryo Tours group early on, the first of which was My Kim Il-sung. across the vast entrance to the Home Village in 1949. The film industry’s heyday came Kim Jong- some insights obligatory statue of Kim Il-sung. A drama about a North Korean in the two decades that followed, This one shows the man the North who escapes from a Japanese- through the 1970s and 1980s, when il’s book into the Koreans call the Great Leader with a administered prison and becomes some of the country’s best-loved group of filmmakers, an old-style an underground operative for the movies were made. -

Coréia & Artes Marciais

Centro Filosófico do Kung Fu - Internacional CORÉIA & ARTES MARCIAIS História e Filosofia Volume 3 www.centrofilosoficodokungfu.com.br “Se atravessarmos a vida convencidos de que a nossa é a única maneira de pensar que existe, vamos acabar perdendo todas as oportunidades que surgem a cada dia” (Akio Morita) Editorial Esta publicação é o 3° volume da coletânea “História e Filosofia das Artes Marciais”, selecionada para cada país que teve destaque na sua formação. Aqui o foco é a Coréia. Todo conteúdo é original da “Wikipédia”, editado e fornecido gratuitamente pelo Centro Filosófico do Kung Fu - Internacional. É muito importante divulgar esta coletânea no meio das artes marciais, independente do praticante; pois estaremos contribuindo para a formação de uma classe de artistas marciais de melhor nível que, com certeza, nosso meio estará se enriquecendo. Bom trabalho ! CORÉIA & ARTES MARCIAIS História e Filosofia Conteúdo 1 Coreia 1 1.1 História ................................................ 1 1.1.1 Gojoseon (2333 a.C. - 37a.C.) ................................ 2 1.1.2 Era dos Três Reinos da Coreia (37 a.C. - 668 d.C.)/ Balhae (713 d.C. - 926 d.C.) ..... 2 1.1.3 Silla Unificada (668 d.C. - 935 d.C.) e Balhae ........................ 2 1.2 Ciência e tecnologia .......................................... 3 1.3 Imigração para o Brasil ........................................ 3 1.4 Ver também .............................................. 3 1.5 Ligações externas ........................................... 3 2 História da Coreia 4 2.1 Ver também .............................................. 7 3 Cronologia da história da Coreia 8 3.1 Pré-História .............................................. 8 3.2 Proto-Três Reinos ........................................... 8 3.3 Três Reinos .............................................. 8 3.4 Silla e Balhae unificada ........................................ 9 3.5 Coreia Dividida ........................................... -

North Korea: Human Rights Update and International Abduction Issues

NORTH KOREA: HUMAN RIGHTS UPDATE AND INTERNATIONAL ABDUCTION ISSUES JOINT HEARING BEFORE THE SUBCOMMITTEE ON ASIA AND THE PACIFIC AND THE SUBCOMMITTEE ON AFRICA, GLOBAL HUMAN RIGHTS AND INTERNATIONAL OPERATIONS OF THE COMMITTEE ON INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES ONE HUNDRED NINTH CONGRESS SECOND SESSION APRIL 27, 2006 Serial No. 109–167 Printed for the use of the Committee on International Relations ( Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.house.gov/international—relations U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 27–228PDF WASHINGTON : 2006 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2250 Mail: Stop SSOP, Washington, DC 20402–0001 VerDate Mar 21 2002 17:18 Jul 11, 2006 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 F:\WORK\AP\042706\27228.000 HINTREL1 PsN: SHIRL COMMITTEE ON INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS HENRY J. HYDE, Illinois, Chairman JAMES A. LEACH, Iowa TOM LANTOS, California CHRISTOPHER H. SMITH, New Jersey, HOWARD L. BERMAN, California Vice Chairman GARY L. ACKERMAN, New York DAN BURTON, Indiana ENI F.H. FALEOMAVAEGA, American ELTON GALLEGLY, California Samoa ILEANA ROS-LEHTINEN, Florida DONALD M. PAYNE, New Jersey DANA ROHRABACHER, California SHERROD BROWN, Ohio EDWARD R. ROYCE, California BRAD SHERMAN, California PETER T. KING, New York ROBERT WEXLER, Florida STEVE CHABOT, Ohio ELIOT L. ENGEL, New York THOMAS G. TANCREDO, Colorado WILLIAM D. DELAHUNT, Massachusetts RON PAUL, Texas GREGORY W. MEEKS, New York DARRELL ISSA, California BARBARA LEE, California JEFF FLAKE, Arizona JOSEPH CROWLEY, New York JO ANN DAVIS, Virginia EARL BLUMENAUER, Oregon MARK GREEN, Wisconsin SHELLEY BERKLEY, Nevada JERRY WELLER, Illinois GRACE F. -

List of Presidents of the Presidents United Nations General Assembly

Sixty-seventh session of the General Assembly To convene on United Nations 18 September 2012 List of Presidents of the Presidents United Nations General Assembly Session Year Name Country Sixty-seventh 2012 Mr. Vuk Jeremić (President-elect) Serbia Sixty-sixth 2011 Mr. Nassir Abdulaziz Al-Nasser Qatar Sixty-fifth 2010 Mr. Joseph Deiss Switzerland Sixty-fourth 2009 Dr. Ali Abdussalam Treki Libyan Arab Jamahiriya Tenth emergency special (resumed) 2009 Father Miguel d’Escoto Brockmann Nicaragua Sixty-third 2008 Father Miguel d’Escoto Brockmann Nicaragua Sixty-second 2007 Dr. Srgjan Kerim The former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia Tenth emergency special (resumed twice) 2006 Sheikha Haya Rashed Al Khalifa Bahrain Sixty-first 2006 Sheikha Haya Rashed Al Khalifa Bahrain Sixtieth 2005 Mr. Jan Eliasson Sweden Twenty-eighth special 2005 Mr. Jean Ping Gabon Fifty-ninth 2004 Mr. Jean Ping Gabon Tenth emergency special (resumed) 2004 Mr. Julian Robert Hunte Saint Lucia (resumed twice) 2003 Mr. Julian Robert Hunte Saint Lucia Fifty-eighth 2003 Mr. Julian Robert Hunte Saint Lucia Fifty-seventh 2002 Mr. Jan Kavan Czech Republic Twenty-seventh special 2002 Mr. Han Seung-soo Republic of Korea Tenth emergency special (resumed twice) 2002 Mr. Han Seung-soo Republic of Korea (resumed) 2001 Mr. Han Seung-soo Republic of Korea Fifty-sixth 2001 Mr. Han Seung-soo Republic of Korea Twenty-sixth special 2001 Mr. Harri Holkeri Finland Twenty-fifth special 2001 Mr. Harri Holkeri Finland Tenth emergency special (resumed) 2000 Mr. Harri Holkeri Finland Fifty-fifth 2000 Mr. Harri Holkeri Finland Twenty-fourth special 2000 Mr. Theo-Ben Gurirab Namibia Twenty-third special 2000 Mr. -

The United Nations at 70 Isbn: 978-92-1-101322-1

DOUBLESPECIAL DOUBLESPECIAL asdf The magazine of the United Nations BLE ISSUE UN Chronicle ISSUEIS 7PMVNF-**t/VNCFSTt Rio+20 THE UNITED NATIONS AT 70 ISBN: 978-92-1-101322-1 COVER.indd 2-3 8/19/15 11:07 AM UNDER-SECRETARY-GENERAL FOR COMMUNICATIONS AND PUBLIC INFORMATION Cristina Gallach DIRECTOR OF PUBLICATION Maher Nasser EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Ramu Damodaran EDITOR Federigo Magherini ART AND DESIGN Lavinia Choerab EDITORIAL ASSISTANTS Lyubov Ginzburg, Jennifer Payulert, Jason Pierce SOCIAL MEDIA ASSISTANT Maria Laura Placencia The UN Chronicle is published quarterly by the Outreach Division of the United Nations Department of Public Information. Please address all editorial correspondence: By e-mail [email protected] By phone 1 212 963-6333 By fax 1 917 367-6075 By mail UN Chronicle, United Nations, Room S-920 New York, NY 10017, USA Subscriptions: Customer service in the USA: United Nations Publications Turpin Distribution Service PO Box 486 New Milford, CT 06776-0486 USA Email: [email protected] Web: ebiz.turpin-distribution.com Tel +1-860-350-0041 Fax +1-860-350-0039 Customer service in the UK: United Nations Publications Turpin Distribution Service Pegasus Drive, Stratton Business Park Biggleswade SG18 8TQ United Kingdom Email: [email protected] Web: ebiz.turpin-distribution.com Tel +1 44 (0) 1767 604951 Fax +1 44 (0) 1767 601640 Reproduction: Articles contained in this issue may be reproduced for educational purposes in line with fair use. Please send a copy of the reprint to the editorial correspondence address shown above. However, no part may be reproduced for commercial purposes without the expressed written consent of the Secretary, Publications Board, United Nations, Room S-949 New York, NY 10017, USA © 2015 United Nations. -

High-Level Seminar on Peacebuilding, National Reconciliation and Democratization in Asia (Venue: UN University) General Chairman: Mr

High-Level Seminar on Peacebuilding, National Reconciliation and Democratization in Asia (Venue: UN University) General Chairman: Mr. Yasushi Akashi Introductory remarks: Mr. Yasushi Akashi, Representative of the Government of Japan on Peace-Building, Rehabilitation 9:00- Opening and Reconstruction of Sri Lanka Session 9:05- Keynote Speech: H.E. Mr. Fumio Kishida, Minister for Foreign Affairs, Japan H.E. Dr. José Ramos-Horta, Former President , The Democratic Republic of Timor-Leste (Chair of the High-Level Independent Panel on UN Peace Operations) 9:20 - 10:20 Mr. Mangala Samaraweera, Minister of Foreign Affairs , the Government of Sri Lanka Speech session H.E. Al Haj Murad Ebrahim, Chairman of Moro Islamic Liberation Front (MILF) Mr. Yohei Sasakawa, Special Envoy of the Government of Japan for National Reconciliation in Myanmar Morning Chair: Dr. David Malone, Rector of the United Nations University Session H.E. Dr. Surin Pitsuwan, Former Secretary-General of ASEAN 10:30 - 12:00 Dr. Akihiko Tanaka, President of the Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) Interactive session Ms. Noeleen Heyzer, Special Advisor of the UN Secretary-General for Timor-Leste Dr. Takashi Shiraishi, President of the National Graduate Institute for Policy Studies Prof. Akiko Yamanaka, Special Ambassador for Peacebuilding, Japan Panel Discussion 1 Panel Discussion 2 Panel Discussion 3 Consolidation of Peace and Socio- Harmonization in Diversity and Peacebuilding and Women and Children Economic Development (Politico- Moderation (Socio-Cultural Aspect) Economic Aspect) 【Moderator】 【Moderator】 【Moderator】 Dr. Toshiya Hoshino, Professor, Vice Mr. Sebastian von Einsiedel, Director, Prof. Akiko Yuge, Professor, Hosei President, Osaka University the Centre for Policy Research, United University (Former Director, Bureau of Nations University Management, UNDP) 【Panelists】 【Panelists】 【Panelists】 <Cambodia> <Malaysia> <Philippines> H.E.