Free People of Color in the Vieux Carré of New

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Program from the Production

STC Board of Trustees Board of Trustees Stephen A. Hopkins Emeritus Trustees Michael R. Klein, Chair Lawrence A. Hough R. Robert Linowes*, Robert E. Falb, Vice Chair W. Mike House Founding Chairman John Hill, Treasurer Jerry J. Jasinowski James B. Adler Pauline Schneider, Secretary Norman D. Jemal Heidi L. Berry* Michael Kahn, Artistic Director Scott Kaufmann David A. Brody* Kevin Kolevar Melvin S. Cohen* Trustees Abbe D. Lowell Ralph P. Davidson Nicholas W. Allard Bernard F. McKay James F. Fitzpatrick Ashley M. Allen Eleanor Merrill Dr. Sidney Harman* Stephen E. Allis Melissa A. Moss Lady Manning Anita M. Antenucci Robert S. Osborne Kathleen Matthews Jeffrey D. Bauman Stephen M. Ryan William F. McSweeny Afsaneh Beschloss K. Stuart Shea V. Sue Molina William C. Bodie George P. Stamas Walter Pincus Landon Butler Lady Westmacott Eden Rafshoon Dr. Paul Carter Rob Wilder Emily Malino Scheuer* Chelsea Clinton Suzanne S. Youngkin Lady Sheinwald Dr. Mark Epstein Mrs. Louis Sullivan Andrew C. Florance Ex-Officio Daniel W. Toohey Dr. Natwar Gandhi Chris Jennings, Sarah Valente Miles Gilburne Managing Director Lady Wright Barbara Harman John R. Hauge * Deceased 3 Dear Friend, Table of Contents I am often asked to choose my favorite Shakespeare play, and Henry IV, Parts 1 and 2 Title Page 5 it is very easy for me to answer immediately Henry IV, Parts 1 The Play of History and 2. In my opinion, there is by Drew Lichtenberg 6 no other play in the English Synopsis: Henry IV, Part 1 9 language which so completely captures the complexity and Synopsis: Henry IV, Part 2 10 diversity of an entire world. -

Pdf2019.04.08 Fontana V. City of New Orleans.Pdf

Case 2:19-cv-09120 Document 1 Filed 04/08/19 Page 1 of 16 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT EASTERN DISTRICT OF LOUISIANA LUKE FONTANA, Plaintiff, CIVIL ACTION NO.: v. JUDGE: The CITY OF NEW ORLEANS; MAYOR LATOYA CANTRELL, in her official capacity; MICHAEL HARRISON, FORMER MAGISTRATE JUDGE: SUPERINTENDENT OF THE NEW ORLEANS POLICE DEPARTMENT, in his official capacity; SHAUN FERGUSON, SUPERINTENDENT OF THE NEW ORLEANS POLICE DEPARTMENT, in his official capacity; and NEW ORLEANS POLICE OFFICERS BARRY SCHECHTER, SIDNEY JACKSON, JR. and ANTHONY BAKEWELL, in their official capacities, Defendants. COMPLAINT INTRODUCTION 1. For more than five years, the City of New Orleans (the “City”) has engaged in an effort to stymie free speech in public spaces termed “clean zones.” Beginning with the 2013 Super Bowl, the City has enacted zoning ordinances to temporarily create such “clean zones” in which permits, advertising, business transactions, and commercial activity are strictly prohibited. Clean zones have been enacted for various public events including the 1 Case 2:19-cv-09120 Document 1 Filed 04/08/19 Page 2 of 16 Superbowl, French Quarter Festival, Satchmo Festival and Essence Festival. These zones effectively outlaw the freedom of expression in an effort to protect certain private economic interests. The New Orleans Police Department (“NOPD”) enforces the City’s “clean zones” by arresting persons engaged in public speech perceived as inimical to those interests. 2. During the French Quarter Festival in April 2018, Plaintiff Luke Fontana was doing what he has done for several years: standing behind a display table on the Moonwalk near Jax Brewery by the Mississippi riverfront. -

Title: Title: Title

Title: 45 Seconds from Broadway Author: Simon, Neil Publisher: Samuel French 2003 Description: roy comedy - friendship - Broadway twelve characters six male; six female two acts interior set; running time: more than 120 minutes; 1 setting From America's master of Contemporary Broadway Comedy, here is another revealing comedy behind the scenes in the entertainment world, this time near the heart of the theatre district. 45 Seconds from Broadway takes place in the legendary "Polish Tea Room" on New York's 47th Street. Here Broadway theatre personalities washed-up and on-the-rise, gather to schmooz even as they Title: Aberhart Summer, The Author: Massing, Conni Publisher: NeWest Press 1999 Description: roy comedy - historical - Alberta playwright - Canadian eleven characters eight male; three female two acts "Based on Bruce Allen Powe's 1984 novel [of the same name], Massing's marvelous play is at once a gripping Alberta history lesson, a sweetly nostalgic comedy and a cracking-good-murder-mystery, all rolled up into one big, bright ball of theatrical energy and verve..." Calgary Herald "At its best, Aberhart Summer is a vivid and unsentimental depiction of small-town Canadian life in Title: Accidents Happen Seven short plays Author: DeAngelis, J. Michael Barry, Pete Publisher: Samuel French 2010 Description: roy comedy large cast flexible casting seven one acts Seven of The Porch Room's best short plays collected together into an evening of comedy that proves that no matter what you plan for - accidents happen. The shorts can be performed together as a full-length show or on their own as one acts. -

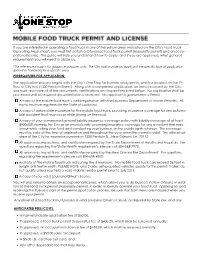

If You Are Interested in Operating a Food Truck in Any of the Yellow Areas

If you are interested in operating a food truck in any of the yellow areas indicated on the City’s Food Truck Operating Areas map*, you must first obtain a City-issued food truck permit (mayoralty permit) and an occu- pational license. This guide will help you understand how to apply, and if you are approved, what general requirements you will need to abide by. *The referenced map is for guidance purposes only. The City shall provide an applicant the specific type of application (permit or franchise) for a specific area. PREREQUISITES FOR APPLICATION: The application process begins with the City’s One Stop for licenses and permits, which is located on the 7th floor of City Hall (1300 Perdido Street). Along with a completed application, on forms provided by the City, you must also have all of the documents, certifications and inspections listed below. No application shall be processed until all required documentation is received. No applicant is guaranteed a Permit. A copy of the mobile food truck’s valid registration with the Louisiana Department of Motor Vehicles. All trucks must be registered in the State of Louisiana. A copy of automobile insurance for the mobile food truck, providing insurance coverage for any automo- bile accident that may occur while driving on the road. A copy of your commercial general liability insurance coverage policy with liability coverage of at least $500,000, naming the City as an insured party, providing insurance coverage for any accident that may occur while selling your food and conducting your business on the public rights-of-ways. -

Guide to Gwens Databases

THE LOUISIANA SLAVE DATABASE AND THE LOUISIANA FREE DATABASE: 1719-1820 1 By Gwendolyn Midlo Hall This is a description of and user's guide to these databases. Their usefulness in historical interpretation will be demonstrated in several forthcoming publications by the author including several articles in preparation and in press and in her book, The African Diaspora in the Americas: Regions, Ethnicities, and Cultures (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, forthcoming 2000). These databases were created almost entirely from original, manuscript documents located in courthouses and historical archives throughout the State of Louisiana. The project lasted 15 years but was funded for only five of these years. Some records were entered from original manuscript documents housed in archives in France, in Spain, and in Cuba and at the University of Texas in Austin as well. Some were entered from published books and journals. Some of the Atlantic slave trade records were entered from the Harvard Dubois Center Atlantic Slave Trade Dataset. Information for a few records was supplied from unpublished research of other scholars. 2 Each record represents an individual slave who was described in these documents. Slaves were listed, and descriptions of them were recorded in documents in greater or lesser detail when an estate of a deceased person who owned at least one slave was inventoried, when slaves were bought and sold, when they were listed in a will or in a marriage contract, when they were mortgaged or seized for debt or because of the criminal activities of the master, when a runaway slave was reported missing, or when slaves, mainly recaptured runaways, testified in court. -

MACBETH Classic Stage Company JOHN DOYLE, Artistic Director TONI MARIE DAVIS, Chief Operating Officer/GM Presents MACBETH by WILLIAM SHAKESPEARE

MACBETH Classic Stage Company JOHN DOYLE, Artistic Director TONI MARIE DAVIS, Chief Operating Officer/GM presents MACBETH BY WILLIAM SHAKESPEARE WITH BARZIN AKHAVAN, RAFFI BARSOUMIAN, NADIA BOWERS, N’JAMEH CAMARA, ERIK LOCHTEFELD, MARY BETH PEIL, COREY STOLL, BARBARA WALSH, ANTONIO MICHAEL WOODARD COSTUME DESIGN LIGHTING DESIGN SOUND DESIGN ANN HOULD-WARD SOLOMON WEISBARD MATT STINE FIGHT DIRECTOR PROPS SUPERVISOR THOMAS SCHALL ALEXANDER WYLIE ASSOCIATE ASSOCIATE ASSOCIATE SCENIC DESIGN COSTUME DESIGN SOUND DESIGN DAVID L. ARSENAULT AMY PRICE AJ SURASKY-YSASI PRESS PRODUCTION CASTING REPRESENTATIVES STAGE MANAGER TELSEY + COMPANY BLAKE ZIDELL AND BERNITA ROBINSON KARYN CASL, CSA ASSOCIATES ASSISTANT DESTINY LILLY STAGE MANAGER JESSICA FLEISCHMAN DIRECTED AND DESIGNED BY JOHN DOYLE MACBETH (in alphabetical order) Macduff, Captain ............................................................................ BARZIN AKHAVAN Malcolm ......................................................................................... RAFFI BARSOUMIAN Lady Macbeth ....................................................................................... NADIA BOWERS Lady Macduff, Gentlewoman ................................................... N’JAMEH CAMARA Banquo, Old Siward ......................................................................ERIK LOCHTEFELD Duncan, Old Woman .........................................................................MARY BETH PEIL Macbeth..................................................................................................... -

The Port of New Orleans: an Economic History, 1821-1860. (Volumes I and Ii)

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1985 The orP t of New Orleans: an Economic History, 1821-1860. (Volumes I and II) (Trade, Commerce, Slaves, Louisiana). Thomas E. Redard Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Redard, Thomas E., "The orP t of New Orleans: an Economic History, 1821-1860. (Volumes I and II) (Trade, Commerce, Slaves, Louisiana)." (1985). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 4151. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/4151 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This reproduction was made from a copy of a manuscript sent to us for publication and microfilming. While the most advanced technology has been used to pho tograph and reproduce this manuscript, the quality of the reproduction Is heavily dependent upon the quality of the material submitted. Pages In any manuscript may have Indistinct print. In all cases the best available copy has been filmed. The following explanation of techniques Is provided to help clarify notations which may appear on this reproduction. 1. Manuscripts may not always be complete. When It Is not possible to obtain missing pages, a note appears to Indicate this. 2. When copyrighted materials are removed from the manuscript, a note ap pears to Indicate this. -

African Reflections on the American Landscape

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior National Center for Cultural Resources African Reflections on the American Landscape IDENTIFYING AND INTERPRETING AFRICANISMS Cover: Moving clockwise starting at the top left, the illustrations in the cover collage include: a photo of Caroline Atwater sweeping her yard in Orange County, NC; an orthographic drawing of the African Baptist Society Church in Nantucket, MA; the creole quarters at Laurel Valley Sugar Plantation in Thibodaux, LA; an outline of Africa from the African Diaspora Map; shotgun houses at Laurel Valley Sugar Plantation; details from the African Diaspora Map; a drawing of the creole quarters at Laurel Valley Sugar Plantation; a photo of a banjo and an African fiddle. Cover art courtesy of Ann Stephens, Cox and Associates, Inc. Credits for the illustrations are listed in the publication. This publication was produced under a cooperative agreement between the National Park Service and the National Conference of State Historic Preservation Officers. African Reflections on the American Landscape IDENTIFYING AND INTERPRETING AFRICANISMS Brian D. Joyner Office of Diversity and Special Projects National Center for Cultural Resources National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior 2003 Ta b le of Contents Executive Summary....................................................iv Acknowledgments .....................................................vi Chapter 1 Africa in America: An Introduction...........................1 What are Africanisms? ......................................2 -

Asides Magazine

2014|2015 SEASON Issue 5 TABLE OF Dear Friend, Queridos amigos: CONTENTS Welcome to Sidney Harman Bienvenidos al Sidney Harman Hall y a la producción Hall and to this evening’s de esta noche de El hombre de La Mancha. Personalmente, production of Man of La Mancha. 2 Title page The opening line of Don esta obra ocupa un espacio cálido pero enreversado en I have a personally warm and mi corazón al haber sido testigo de su nacimiento. Era 3 Musical Numbers complicated spot in my heart Quixote is as resonant in el año 1965 en la Casa de Opera Goodspeed en East for this show, since I was a Latino cultures as Dickens, Haddam, Connecticut. Estaban montando la premier 5 Cast witness to its birth. It was in 1965, at the Goodspeed Twain, or Austen might mundial, dirigida por Albert Marre. Se suponía que Opera House in East Haddam, CT. They were Albert iba a dirigir otra premier para ellos, la cual iba 7 About the Author mounting the world premiere, directed by Albert be in English literature. a presentarse en repertorio con La Mancha, pero Albert Marre. Now, Albert was supposed to direct another 10 Director’s Words world premiere for them, which was going to run In recognition of consiguió un trabajo importante en Hollywood y les recomendó a otro director: a mí. 12 The Impossible Musical in repertory with La Mancha, but he got a big job in Cervantes’ legacy, we at Hollywood, and he recommended another director. by Drew Lichtenberg That was me. STC want to extend our Así que fui a Goodspeed y dirigí la otra obra. -

New Marigny” GMAC Cingular Wireless Verizon Wireless Sprint/Sprint PCS Tion of I-10 Over a Main 1831 Pontchartrain Railroad (A.K.A

Annual Neighborhood Events • August: Night Out Against Crime LIVING WITH HISTORY • October: Preservation Resource Center’s IN NEW ORLEANS’ NEIGHBORHOODS Rebuilding Together program Neighborhood Organizations eeww • Crescent City Peace Alliance NN • Faubourg Franklin Foundation rriiggnnyy • Faubourg St. Roch Improvement Association MMaa onvenient to both New Orleans’ Central 1798 Pierre Philippe de Marigny acquires Business District and the Vieux Carré, historic New Dubreuil Plantation Circle Food Store 1800 Marquis Antoine Xavier Bernard 1522 St. Bernard Avenue Marigny, also called Faubourg St. Roch, has all the Philippe de Marigny de Mandeville A TRADITION IN NEW ORLEANS makings of a desirable inherits from Pierre Philippe de Marigny We are still here and still serving the community. C downtown neighbor- 1803 Louisiana Purchase Saving You Money on Groceries 1806 Nicholas de Finiels develops street Services, Bill Payments hood. Industrialization plan for Marigny; engineer Barthelemy BellSouth • Entergy • Sewer & Water Board and flight to the suburbs Lafon contracts to lay out the street grid We Accept Payment For: hit this area hard, how- 1810 Marigny extends original subdivision, American Express E Mobil (formerly Voicestream) MCI/MCI Worldcom Wireless Ford Motor Credit asking Lafon to plot area now known Chevron Toyota Financial Services Shell Gas Card Macy’s ever, and the construc- Discover Card AT & T Target Visa Card Sam’s Club as “New Marigny” GMAC Cingular Wireless Verizon Wireless Sprint/Sprint PCS tion of I-10 over a main 1831 Pontchartrain Railroad (a.k.a. “Smoky Mervyn’s Dish Network Capital One Credit Card Texaco Sears JC Penney Dillard’s Wal-Mart thoroughfare in the Mary”), 2nd oldest railroad in U.S., opens on Elysian Fields 1960s sent many resi- 1832 World’s largest cotton press opens on dents and businesses present Press Street packing. -

Press Street: a Concept for Preserving, Reintroducing and Fostering Local History Brian J

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Master's Theses Graduate School 2005 Press Street: a concept for preserving, reintroducing and fostering local history Brian J. McBride Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses Part of the Landscape Architecture Commons Recommended Citation McBride, Brian J., "Press Street: a concept for preserving, reintroducing and fostering local history" (2005). LSU Master's Theses. 2952. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses/2952 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Master's Theses by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. PRESS STREET: A CONCEPT FOR PRESERVING, REINTRODUCING, AND FOSTERING LOCAL HISTORY A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agriculture and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Landscape Architecture in The School of Landscape Architecture by Brian J. McBride B.S., Louisiana State University, 1994 May 2005 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The author would like to recognize a number of people for providing assistance, insight and encouragement during the research and writing of this thesis. Special thanks to the faculty and staff of the School of Landscape Architecture, especially to Max Conrad, Van Cox and Kevin Risk. To all without whom I could not have completed this process, especially my parents for their persistence; and my wife, for her continued love and support. -

The Enslaved Families of Fontainebleau

THE ENSLAVED FAMILIES OF FONTAINEBLEAU A Summary for the 2019 Dedication of the Historic Marker FEBRUARY 19, 2019 RESEARCH BY JACKSON CANTRELL, IMAGES COLLATED BY LEANNE CANTRELL P a g e | 1 Introduction Before we can discuss the lives of the enslaved families who once resided at Fontainebleau, it is helpful to know how and why the plantation was created in the first place. For residents of the city of Mandeville, Louisiana, stories about the town’s founding father, Bernard de Marigny de Mandeville are widely known. When he and his siblings inherited their father’s vast estate (some historians claim his holdings may have been worth $7 million or around $200 million in today’s value) he was just shy of 16 years old. Bernard had seen a life of indulgence and privilege like few other teenagers ever had. His mentors did their best to educate him and help him mature before he arrived at the legal age of maturity. As a 21-year-old in 1806 New Orleans, he began subdividing the family’s plantation there into residential lots that would become the suburb known as the Fauberg Marigny. Two decades later, Bernard had by then helped facilitate the winning of The War of 1812 and served as President of the Louisiana State Senate. He began looking toward the north shore of Lake Pontchartrain as an area where he might purchase and again subdivide land. His goal was to create a resort town near pine forests, the lakefront, and fresh-water bayous. While laying out the plans for his little city, he created street names to honor various statesmen and war heroes.