La Cenerentola

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

01-25-2020 Boheme Eve.Indd

GIACOMO PUCCINI la bohème conductor Opera in four acts Marco Armiliato Libretto by Giuseppe Giacosa and production Franco Zeffirelli Luigi Illica, based on the novel Scènes de la Vie de Bohème by Henri Murger set designer Franco Zeffirelli Saturday, January 25, 2020 costume designer 8:00–11:05 PM Peter J. Hall lighting designer Gil Wechsler revival stage director Gregory Keller The production of La Bohème was made possible by a generous gift from Mrs. Donald D. Harrington Revival a gift of Rolex general manager Peter Gelb This season’s performances of La Bohème jeanette lerman-neubauer and Turandot are dedicated to the memory music director Yannick Nézet-Séguin of Franco Zeffirelli. 2019–20 SEASON The 1,344th Metropolitan Opera performance of GIACOMO PUCCINI’S la bohème conductor Marco Armiliato in order of vocal appearance marcello muset ta Artur Ruciński Susanna Phillips rodolfo a customhouse serge ant Roberto Alagna Joseph Turi colline a customhouse officer Christian Van Horn Edward Hanlon schaunard Elliot Madore* benoit Donald Maxwell mimì Maria Agresta Tonight’s performances of parpignol the roles of Mimì Gregory Warren and Rodolfo are underwritten by the alcindoro Jan Shrem and Donald Maxwell Maria Manetti Shrem Great Singers Fund. Saturday, January 25, 2020, 8:00–11:05PM MARTY SOHL / MET OPERA Roberto Alagna as Chorus Master Donald Palumbo Rodolfo and Maria Musical Preparation Caren Levine*, Joshua Greene, Agresta as Mimì in Jonathan C. Kelly, and Patrick Furrer Puccini’s La Bohème Assistant Stage Directors Mirabelle Ordinaire and J. Knighten Smit Met Titles Sonya Friedman Stage Band Conductor Joseph Lawson Children’s Chorus Director Anthony Piccolo Italian Coach Loretta Di Franco Prompter Joshua Greene Associate Designer David Reppa Scenery, properties, and electrical props constructed and painted in Metropolitan Opera Shops Costumes executed by Metropolitan Opera Costume Department Wigs and Makeup executed by Metropolitan Opera Wig and Makeup Department Ladies millinery by Reggie G. -

La Sonnambula 3 Content

Florida Grand Opera gratefully recognizes the following donors who have provided support of its education programs. Study Guide 2012 / 2013 Batchelor MIAMI BEACH Foundation Inc. Dear Friends, Welcome to our exciting 2012-2013 season! Florida Grand Opera is pleased to present the magical world of opera to the diverse audience of © FLORIDA GRAND OPERA © FLORIDA South Florida. We begin our season with a classic Italian production of Giacomo Puccini’s La bohème. We continue with a supernatural singspiel, Mozart’s The Magic Flute and Vincenzo Bellini’s famous opera La sonnam- bula, with music from the bel canto tradition. The main stage season is completed with a timeless opera with Giuseppe Verdi’s La traviata. As our RHWIEWSRÁREPI[ILEZIEHHIHERI\XVESTIVEXSSYVWGLIHYPIMRSYV continuing efforts to be able to reach out to a newer and broader range of people in the community; a tango opera María de Buenoa Aires by Ástor Piazzolla. As a part of Florida Grand Opera’s Education Program and Stu- dent Dress Rehearsals, these informative and comprehensive study guides can help students better understand the opera through context and plot. )EGLSJXLIWIWXYH]KYMHIWEVIÁPPIH[MXLLMWXSVMGEPFEGOKVSYRHWWXSV]PMRI structures, a synopsis of the opera as well as a general history of Florida Grand Opera. Through this information, students can assess the plotline of each opera as well as gain an understanding of the why the librettos were written in their fashion. Florida Grand Opera believes that education for the arts is a vital enrich- QIRXXLEXQEOIWWXYHIRXW[IPPVSYRHIHERHLIPTWQEOIXLIMVPMZIWQSVI GYPXYVEPP]JYPÁPPMRK3RFILEPJSJXLI*PSVMHE+VERH3TIVE[ILSTIXLEX A message from these study guides will help students delve further into the opera. -

Aureliano in Palmira Gioachino Rossini (1792-1868) : Felice Romani (1788-1865)

1/3 Data Livret de Aureliano in Palmira Gioachino Rossini (1792-1868) : Felice Romani (1788-1865) Langue : Italien Genre ou forme de l’œuvre : Œuvres musicales Date : 1813 Note : "Dramma serio" en 2 actes créé à Milan, Teatro alla Scala, le 26 décembre 1813. - Livret de Felice Romani d'après "Zenobia di Palmira" d'Anfossi Éditions de Aureliano in Palmira (19 ressources dans data.bnf.fr) Partitions (13) Cavatina del maestro , Gioachino Rossini Quartetto pastorale , Gioachino Rossini Rossini nell' Aureliano in (1792-1868), Paris : Pacini nell'Aureliano in Palmira. (1792-1868), Paris : Pacini Palmira. [Chant et piano] , [s.d.] Composto dal maestro , [s.d.] Rossini. [Chant et accompagnement de piano] Aureliano in Palmira, opéra , Gioachino Rossini Cavatina nell'Aureliano in , Gioachino Rossini in due atti, musica di (1792-1868), Paris : Palmira, musica del (1792-1868), Paris : Pacini Rossini [Partition chant et Schonenberger , [s.d.] maestro Rossini. [Chant et , [s.d.] piano] piano] Terzettino nel Aureliano in , Gioachino Rossini Cavatina nell'Aureliano in , Gioachino Rossini Palmira del maestro (1792-1868), Paris : Pacini Palmira del maestro (1792-1868), Paris : Pacini Rossini. [Chant et piano] , [s.d.] Rossini. [Chant et piano] , [s.d.] Aureliano in Palmira. Mille sospiri e lagrimé. - [7] Aureliano in Palmira , Felice Romani (2019) (1788-1865), Gioachino Rossini (1792-1868), Pesaro : Fondazione Rossini data.bnf.fr 2/3 Data Aureliano in Palmira, opera , Felice Romani Mille sospiri e Lagrime. Air , Gioachino Rossini in 2 atti (1788-1865), Gioachino à 2 v. tiré d'Aureliano in (1792-1868), Paris : [s.n.] , (1855) Rossini (1792-1868), Paris Palmira 1823 : Schonenberger , [1855] (1823) Ecco mi, ingiustinumi. -

Metropolitan Opera 19-20 Season Press Release

Updated: November 12, 2019 New Productions of Porgy and Bess, Der Fliegende Holländer, and Wozzeck, and Met Premieres of Agrippina and Akhnaten Headline the Metropolitan Opera’s 2019–20 Season Yannick Nézet-Séguin, in his second season as Music Director, conducts the new William Kentridge production of Wozzeck, as well as two revivals, Met Orchestra concerts at Carnegie Hall, and a New Year’s Eve Puccini Gala starring Anna Netrebko Sunday matinee performances are offered for the first time From Roberto Alagna to Sonya Yoncheva, favorite Met singers return Debuting conductors are Karen Kamensek, Antonello Manacorda, and Vasily Petrenko; returning maestros include Valery Gergiev and Sir Simon Rattle New York, NY (February 20, 2019)—The Metropolitan Opera today announced its 2019–20 season, which opens on September 23 with a new production of the Gershwins’ classic American opera Porgy and Bess, last performed at the Met in 1990, starring Eric Owens and Angel Blue, directed by James Robinson and conducted by David Robertson. Philip Glass’s Akhnaten receives its Met premiere with Anthony Roth Costanzo as the title pharaoh and J’Nai Bridges as Nefertiti, in a celebrated staging by Phelim McDermott and conducted by Karen Kamensek in her Met debut. Acclaimed visual artist and stage director William Kentridge directs a new production of Berg’s Wozzeck, starring Peter Mattei and Elza van den Heever, and led by the Met’s Jeanette Lerman-Neubauer Music Director Yannick Nézet-Séguin. In another Met premiere, Sir David McVicar stages the black comedy of Handel’s Agrippina, starring Joyce DiDonato as the conniving empress with Harry Bicket on the podium. -

Il Trovatore Was Made Stage Director Possible by a Generous Gift from Paula Williams the Annenberg Foundation

ilGIUSEPPE VERDItrovatore conductor Opera in four parts Marco Armiliato Libretto by Salvadore Cammarano and production Sir David McVicar Leone Emanuele Bardare, based on the play El Trovador by Antonio García Gutierrez set designer Charles Edwards Tuesday, September 29, 2015 costume designer 7:30–10:15 PM Brigitte Reiffenstuel lighting designed by Jennifer Tipton choreographer Leah Hausman The production of Il Trovatore was made stage director possible by a generous gift from Paula Williams The Annenberg Foundation The revival of this production is made possible by a gift of the Estate of Francine Berry general manager Peter Gelb music director James Levine A co-production of the Metropolitan Opera, Lyric Opera of Chicago, and the San Francisco principal conductor Fabio Luisi Opera Association 2015–16 SEASON The 639th Metropolitan Opera performance of GIUSEPPE VERDI’S il trovatore conductor Marco Armiliato in order of vocal appearance ferr ando Štefan Kocán ines Maria Zifchak leonor a Anna Netrebko count di luna Dmitri Hvorostovsky manrico Yonghoon Lee a zucena Dolora Zajick a gypsy This performance Edward Albert is being broadcast live on Metropolitan a messenger Opera Radio on David Lowe SiriusXM channel 74 and streamed at ruiz metopera.org. Raúl Melo Tuesday, September 29, 2015, 7:30–10:15PM KEN HOWARD/METROPOLITAN OPERA A scene from Chorus Master Donald Palumbo Verdi’s Il Trovatore Musical Preparation Yelena Kurdina, J. David Jackson, Liora Maurer, Jonathan C. Kelly, and Bryan Wagorn Assistant Stage Director Daniel Rigazzi Italian Coach Loretta Di Franco Prompter Yelena Kurdina Assistant to the Costume Designer Anna Watkins Fight Director Thomas Schall Scenery, properties, and electrical props constructed and painted by Cardiff Theatrical Services and Metropolitan Opera Shops Costumes executed by Lyric Opera of Chicago Costume Shop and Metropolitan Opera Costume Department Wigs and Makeup executed by Metropolitan Opera Wig and Makeup Department Ms. -

L'italiana in ALGERI Di Gioacchino Rossini a TEATRO CON LA LUTE

A TEATRO CON LA LUTE L’ITALIANA IN ALGERI Di Gioacchino Rossini L'italiana in Algeri Dramma giocoso in due atti Musica di Gioachino Rossini Libretto di Angelo Anelli Direttore Gabriele Ferro Regia Maurizio Scaparro Regista collaboratore Orlando Forioso Scene Emanuele Luzzati Costumi Santuzza Calì Luci Bruno Ciulli Assistente ai costumi Paola Tosti Maestro al fortepiano Giuseppe Cinà Orchestra e Coro del Teatro Massimo Allestimento del Teatro Massimo Cast Mustafà Luca Tittoto Elvira Maria Francesca Mazzara Zulma Isabel De Paoli Haly Giovanni Romeo Lindoro Levy Segkpane Isabella Teresa Iervolino Taddeo Francesco Vultaggio Direttore D’Orchestra Gabriele Ferro Ha compiuto gli studi musicali, pianoforte e composizione, diplomandosi presso il Conservatorio Santa Cecilia di Roma. Nel 1970 ha vinto il concorso per giovani direttori d’orchestra della Rai, collaborando da allora con le sue orchestre, quella dell’Accademia di Santa Cecilia e della Scala di Milano per i concerti sinfonici. Ha riscosso un ampio successo internazionale dirigendo i Wiener Symphoniker, i Bamberg Symphoniker, l’Orchestre de la Suisse Ro- mande, l’Orchestre Philharmonique de Radio France, la BBC Symphony Orchestra, l’Orchestra WDR, la Cleveland Orchestra, e la Gewandhaus di Lipsia. Ha inoltre collaborato per molti anni con l’Orchestre National de France. È stato Direttore stabile dell’Orchestra Sinfonica Siciliana (1979-1997), Direttore principale dell’Orchestra della Rai di Roma (1987-1991), Generalmusikdirektor dello Stuttgart Staatstheater (1991-1997), Direttore musicale del Teatro San Carlo di Napoli (1999-2004) e Direttore principale del Teatro Massimo di Palermo (2001-2006). Il suo repertorio spazia dalla musica classica alla contemporanea, nell’ambito della quale ha diretto in prima mondiale opere di Berio, Clementi, Maderna, Stockhausen, Lieti, Nono, Rihm, Battistelli, Betta etc. -

The Italian Girl in Algiers

Opera Box Teacher’s Guide table of contents Welcome Letter . .1 Lesson Plan Unit Overview and Academic Standards . .2 Opera Box Content Checklist . .8 Reference/Tracking Guide . .9 Lesson Plans . .11 Synopsis and Musical Excerpts . .32 Flow Charts . .38 Gioachino Rossini – a biography .............................45 Catalogue of Rossini’s Operas . .47 2 0 0 7 – 2 0 0 8 S E A S O N Background Notes . .50 World Events in 1813 ....................................55 History of Opera ........................................56 History of Minnesota Opera, Repertoire . .67 GIUSEPPE VERDI SEPTEMBER 22 – 30, 2007 The Standard Repertory ...................................71 Elements of Opera .......................................72 Glossary of Opera Terms ..................................76 GIOACHINO ROSSINI Glossary of Musical Terms .................................82 NOVEMBER 10 – 18, 2007 Bibliography, Discography, Videography . .85 Word Search, Crossword Puzzle . .88 Evaluation . .91 Acknowledgements . .92 CHARLES GOUNOD JANUARY 26 –FEBRUARY 2, 2008 REINHARD KEISER MARCH 1 – 9, 2008 mnopera.org ANTONÍN DVOˇRÁK APRIL 12 – 20, 2008 FOR SEASON TICKETS, CALL 612.333.6669 The Italian Girl in Algiers Opera Box Lesson Plan Title Page with Related Academic Standards lesson title minnesota academic national standards standards: arts k–12 for music education 1 – Rossini – “I was born for opera buffa.” Music 9.1.1.3.1 8, 9 Music 9.1.1.3.2 Theater 9.1.1.4.2 Music 9.4.1.3.1 Music 9.4.1.3.2 Theater 9.4.1.4.1 Theater 9.4.1.4.2 2 – Rossini Opera Terms Music -

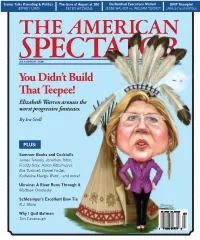

You Didn't Build That Teepee!

Trump Talks Parenting & Politics The Guns of August at 100 Do Botched Executions Matter? UKIP Triumphs! JEFFREY LORD PETER HITCHENS JESSE WALKER vs. WILLIAM TUCKER JAMES DELINGPOLE JULY/AUGUST 2014 A MONTHLY REVIEW EDITED BY R. EMMETT TYRRELL, JR. You Didn’t Build That Teepee! Elizabeth Warren arouses the worst progressive fantasies. By Ira Stoll PLUS: Summer Books and Cocktails James Taranto, Jonathan Tobin, Freddy Gray, Helen Rittelmeyer, Eve Tushnet, Daniel Foster, Katherine Mangu-Ward…and more! Ukraine: A River Runs Through It Matthew Omolesky Schlesinger’s Excellent Bow Tie R.J. Stove Why I Quit Batman Tim Cavanaugh 1 5 1 5 1 5 1 5 25 50 75 95 25 50 75 95 25 50 75 95 25 50 75 95 100 100 100 100 “ The best detector is not merely the one that can pick up radar from the farthest distance, although the Valentine One continues to score best.” — Autoweek Now V1 comes to a touchscreen near you. Introducing the Threat Picture You can see the arrows at work on your compatible iPhone® or AndroidTM device. Check it out… The app is free! Yo u can download V1connection, the app Where’s the radar? It’s in the Box. for free. Go to the app store on your device. When installed, the app automatically runs in Demo Mode. No need to link to V1. Analyze preloaded threat situations on three different screens: on the V1 screen, Arrow in the Box means a threat in the radar zone. on Picture, and on List. Then when you’re ready to put the Threat Picture on duty in your car, order the Bluetooth® communication module directly from us. -

|What to Expect from L'elisir D'amore

| WHAT TO EXPECT FROM L’ELISIR D’AMORE AN ANCIENT LEGEND, A POTION OF QUESTIONABLE ORIGIN, AND THE WORK: a single tear: sometimes that’s all you need to live happily ever after. When L’ELISIR D’AMORE Gaetano Donizetti and Felice Romani—among the most famous Italian An opera in two acts, sung in Italian composers and librettists of their day, respectively—joined forces in 1832 Music by Gaetano Donizetti to adapt a French comic opera for the Italian stage, the result was nothing Libretto by Felice Romani short of magical. An effervescent mixture of tender young love, unforget- Based on the opera Le Philtre table characters, and some of the most delightful music ever written, L’Eli s ir (The Potion) by Eugène Scribe and d’Amore (The Elixir of Love) quickly became the most popular opera in Italy. Daniel-François-Esprit Auber Donizetti’s comic masterpiece arrived at the Metropolitan Opera in 1904, First performed May 12, 1832, at the and many of the world’s most famous musicians have since brought the opera Teatro alla Cannobiana, Milan, Italy to life on the Met’s stage. Today, Bartlett Sher’s vibrant production conjures the rustic Italian countryside within the opulence of the opera house, while PRODUCTION Catherine Zuber’s colorful costumes add a dash of zesty wit. Toss in a feisty Domingo Hindoyan, Conductor female lead, an earnest and lovesick young man, a military braggart, and an Bartlett Sher, Production ebullient charlatan, and the result is a delectable concoction of plot twists, Michael Yeargan, Set Designer sparkling humor, and exhilarating music that will make you laugh, cheer, Catherine Zuber, Costume Designer and maybe even fall in love. -

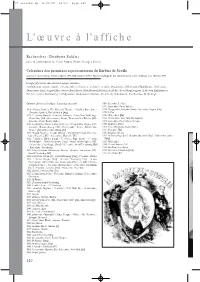

L'œuvre À L'affiche

37 affiche xp 2/06/05 10:13 Page 120 L'œuvre à l'affiche Recherches: Elisabetta Soldini avec la contribution de César Arturo Dillon, Georges Farret Calendrier des premières représentations du Barbier de Séville d’après A. Loewenberg, Annals of Opera 1597-1940, Londres 1978 et Pipers Enzyklopädie des Musiktheaters, éd. C. Dahlhaus et S. Döhring, 1991 Le signe [▼] renvoie aux tableaux des pages suivantes. Sauf indication contraire signalée entre parenthèses, l’œuvre a été chantée en italien: [Ang] anglais, [All] allemand, [Bulg] bulgare, [Cro] croate, [Dan] danois, [Esp] espagnol, [Est] estonien, [Finn] finnois, [Flam] flamand, [Fr] français, [Héb] hébreu, [Hong] hongrois, [Lett] letton, [Lit] Lituanien, [Née] néerlandais, [Nor] norvégien, [Pol] polonais, [Rou] roumain, [Ru] russe, [Serb] serbe, [Slov] slovène, [Sué] suédois, [Tch] tchèque CRÉATION: 20 février 1816, Rome, Teatro Argentina. [▼] 1869: décembre, Le Caire. 1871: 3 novembre, Paris, Athénée. 1818: 10 mars, Londres, Her Majesty’s Theatre. - 16 juillet, Barcelone. - 1874: 29 septembre, Helsinki. [Finn] - 2 décembre, Zagreb. [Cro] 13 octobre, Londres, Covent Garden. [Ang] 1875: Le Cap. 1819: 1er janvier, Munich. - Carnaval, Lisbonne. - 3 mai, New York [Ang] - 1876: Tiflis. - Kiev. [Ru] 27 mai, Graz. [All] - 28 septembre, Vienne, Theater auf der Wieden. [All] - 1883: 23 novembre, New York, Metropolitan. 26 octobre, Paris, Théâtre-Italien. 1884: 8 novembre, Paris, Opéra-Comique. 1820: 6 septembre, Milan, Teatro alla Scala. - 29 septembre, Prague. [All] - 1905 : Ljubljana. [Slov] 3 octobre, Braunschweig. [All] - 16 décembre, Vienne, Kärntnertor- 1913 : 3 mai, Christiania (Oslo). [Norv] Theater. [All] - 18 décembre, Brünn. [All] 1918 : Shanghai. [Ru] 1821: 25 août, Madrid. - 31 août, Odessa. - 19 septembre, Lyon. -

Maria Teresa Grassi

M.T. Grassi, Zenobia, un mito assente, “LANX” 7 (2010), pp. 299-314 Maria Teresa Grassi Zenobia, un mito assente Tra i grandi personaggi femminili della storia romana vanno senza dubbio annoverate due regine straniere, l’egiziana Cleopatra e la siriana Zenobia: entrambe hanno avuto un ruolo di primo piano nelle vicende politiche della loro epoca, ma la fama della prima - una vera star dell’immaginario collettivo - non è neppure paragonabile a quella della seconda.1 La vicenda di Zenobia si svolge nel III secolo d.C., in soli cinque anni, tra il 267 e il 272 d.C., nel settore orientale dell’Impero Romano, ed ha come epicentro la Siria e Palmira, importante città carovaniera posta in un’oasi del deserto siriano, a mezza strada tra l’Eufrate e il Mediterraneo. Di Zenobia abbiamo solo poche immagini, “sfuocate”, dalle monete coniate a suo nome (monete peraltro di grande importanza per ricostruire l’ascesa politica della regina) e nella stessa Palmira ben poco si può ricondurre a Zenobia (qualche grande complesso è stato talora definito come il “palazzo di Zenobia”, ma si tratta di attribuzioni di fantasia2) e scarse sono anche le fonti letterarie ed epigrafiche da cui ricavare qualche dato. Dal punto di vista romanzesco, Zenobia è indubbiamente poco attraente: al contrario di Cleopatra non se ne conoscono gli amori e neppure le circostanze della morte, non ha avuto intorno a sé personaggi di primo piano come Giulio Cesare, Marco Antonio e Augusto. Il suo antagonista, l’imperatore Aureliano, non ha la stessa fama: malgrado le indubbie qualità politiche e militari, è uno dei tanti imperatori del turbolento III secolo d.C. -

Rossini: La Recepción De Su Obra En España

EMILIO CASARES RODICIO Rossini: la recepción de su obra en España Rossini es una figura central en el siglo XIX español. La entrada de su obra a través de los teatros de Barcelona y Madrid se produce a partir de 1815 y trajo como consecuencia su presen- cia en salones y cafés por medio de reducciones para canto de sus obras. Más importante aún es la asunción de la producción rossiniana corno símbolo de la nueva creación lírica europea y, por ello, agitadora del conservador pensamiento musical español; Rossini tuvo una influencia decisi- va en la producción lírica y religiosa de nuestro país, cuyo mejor ejemplo serían las primeras ópe- ras de Ramón Carnicer. Rossini correspondió a este fervor y se rodeó de numerosos españoles, comenzando por su esposa Isabel Colbrand, o el gran tenor y compositor Manuel García, termi- nando por su mecenas y amigo, el banquero sevillano Alejandro Aguado. Rossini is a key figure in nineteenth-century Spain. His output first entered Spain via the theatres of Barcelona and Madrid in 1815 and was subsequently present in salons and cafés in the form of vocal reduc- tions. Even more important is the championing of Rossini's output as a model for modern European stage music which slwok up conservative Spanish musical thought. Rossini liad a decisive influence on die sacred and stage-music genres in Spain, the best example of which are Ramón Carnicer's early operas. Rossini rec- ipricated this fervour and surrounded himself with numerous Spanish musicians, first and foremost, his wife Isabel Colbrand, as well as die great tenor and composer Manuel García and bis patron and friend, the Sevil- lan banker Alejandro Aguado.