01-25-2020 Boheme Eve.Indd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Doctor Atomic

John Adams Doctor Atomic CONDUCTOR Opera in two acts Alan Gilbert Libretto by Peter Sellars, PRODUCTION adapted from original sources Penny Woolcock Saturday, November 8, 2008, 1:00–4:25pm SET DESIGNER Julian Crouch COSTUME DESIGNER New Production Catherine Zuber LIGHTING DESIGNER Brian MacDevitt CHOREOGRAPHER The production of Doctor Atomic was made Andrew Dawson possible by a generous gift from Agnes Varis VIDEO DESIGN and Karl Leichtman. Leo Warner & Mark Grimmer for Fifty Nine Productions Ltd. SOUND DESIGNER Mark Grey GENERAL MANAGER The commission of Doctor Atomic and the original San Peter Gelb Francisco Opera production were made possible by a generous gift from Roberta Bialek. MUSIC DIRECTOR James Levine Doctor Atomic is a co-production with English National Opera. 2008–09 Season The 8th Metropolitan Opera performance of John Adams’s Doctor Atomic Conductor Alan Gilbert in o r d e r o f v o c a l a p p e a r a n c e Edward Teller Richard Paul Fink J. Robert Oppenheimer Gerald Finley Robert Wilson Thomas Glenn Kitty Oppenheimer Sasha Cooke General Leslie Groves Eric Owens Frank Hubbard Earle Patriarco Captain James Nolan Roger Honeywell Pasqualita Meredith Arwady Saturday, November 8, 2008, 1:00–4:25pm This afternoon’s performance is being transmitted live in high definition to movie theaters worldwide. The Met: Live in HD series is made possible by a generous grant from the Neubauer Family Foundation. Additional support for this Live in HD transmission and subsequent broadcast on PBS is provided by the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation. Ken Howard/Metropolitan Opera Gerald Finley Chorus Master Donald Palumbo (foreground) as Musical Preparation Linda Hall, Howard Watkins, Caren Levine, J. -

UNITEL PROUDLY REPRESENTS the INTERNATIONAL TV DISTRIBUTION of Browse Through the Complete Unitel Catalogue of More Than 2,000 Titles At

UNITEL PROUDLY REPRESENTS THE INTERNATIONAL TV DISTRIBUTION OF Browse through the complete Unitel catalogue of more than 2,000 titles at www.unitel.de Date: March 2018 FOR CO-PRODUCTION & PRESALES INQUIRIES PLEASE CONTACT: Unitel GmbH & Co. KG Gruenwalder Weg 28D · 82041 Oberhaching/Munich, Germany Tel: +49.89.673469-613 · Fax: +49.89.673469-610 · [email protected] Ernst Buchrucker Dr. Thomas Hieber Dr. Magdalena Herbst Managing Director Head of Business and Legal Affairs Head of Production [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Tel: +49.89.673469-19 Tel: +49.89.673469-611 Tel: +49.89.673469-862 WORLD SALES C Major Entertainment GmbH Meerscheidtstr. 8 · 14057 Berlin, Germany Tel.: +49.30.303064-64 · [email protected] Elmar Kruse Niklas Arens Nishrin Schacherbauer Managing Director Sales Manager, Director Sales Sales Manager [email protected] & Marketing [email protected] [email protected] Nadja Joost Ira Rost Sales Manager, Director Live Events Sales Manager, Assistant to & Popular Music Managing Director [email protected] [email protected] CONTENT BRITTEN: GLORIANA Susan Bullock/Toby Spence/Kate Royal/Peter Coleman-Wright Conducted by: Paul Daniel OPERAS 3 Staged by: Richard Jones BALLETS 8 Cat. No. A02050015 | Length: 164' | Year: 2016 DONIZETTI: LA FILLE DU RÉGIMENT Natalie Dessay/Juan Diego Flórez/Felicity Palmer Conducted by: Bruno Campanella Staged by: Laurent Pelly Cat. No. A02050065 | Length: 131' | Year: 2016 OPERAS BELLINI: NORMA Sonya Yoncheva/Joseph Calleja/Sonia Ganassi/ Brindley Sherratt/La Fura dels Baus Conducted by: Antonio Pappano Staged by: Àlex Ollé Cat. -

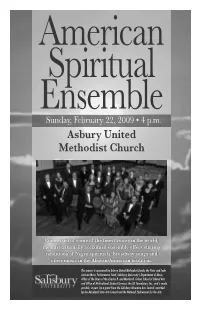

American Spiritual Program Spring 2009

American Spiritual Ensemble Sunday, February 22, 2009 • 4 p.m. Asbury United Methodist Church Comprised of some of the finest voices in the world, the internationally acclaimed ensemble offers stirring renditions of Negro spirituals, Broadway songs and other music in the African-American tradition. The concert is sponsored by Asbury United Methodist Church; the Peter and Judy Jackson Music Performance Fund; Salisbury University’s Department of Music, Office of the Dean of the Charles R. and Martha N. Fulton School of Liberal Arts and Office of Multicultural Student Services; the SU Foundation, Inc.; and is made possible, in part, by a grant from the Salisbury Wicomico Arts Council, awarded by the Maryland State Arts Council and the National Endowment for the Arts. AMERICAN SPIRITUAL ENSEMBLE EVERETT MCCORVEY , F OUNDER AND MUSIC DIRECTOR www.americanspiritualensemble.com PROGRAM Walk Together, Children ............................................................arr. William Henry Smith We Shall Walk Through the Valley in Peace ............................................arr. Moses Hogan Plenty Good Room ......................................................................arr. William Henry Smith Oh, What A Beautiful City! ........................................................................arr. Johnie Dean Mari-Yan Pringle, Jeryl Cunningham, Sopranos I Want Jesus to Walk With Me ....................arr. Eurydice Osterman/Tedrin Blair Lindsay Ricky Little, Baritone Fi-yer, Fi-yer Lord (from the operetta Fi-yer! )......................Hall -

Network Notebook

Network Notebook Fall Quarter 2018 (October - December) 1 A World of Services for Our Affiliates We make great radio as affordable as possible: • Our production costs are primarily covered by our arts partners and outside funding, not from our affiliates, marketing or sales. • Affiliation fees only apply when a station takes three or more programs. The actual affiliation fee is based on a station’s market share. Affiliates are not charged fees for the selection of WFMT Radio Network programs on the Public Radio Exchange (PRX). • The cost of our Beethoven and Jazz Network overnight services is based on a sliding scale, depending on the number of hours you use (the more hours you use, the lower the hourly rate). We also offer reduced Beethoven and Jazz Network rates for HD broadcast. Through PRX, you can schedule any hour of the Beethoven or Jazz Network throughout the day and the files are delivered a week in advance for maximum flexibility. We provide highly skilled technical support: • Programs are available through the Public Radio Exchange (PRX). PRX delivers files to you days in advance so you can schedule them for broadcast at your convenience. We provide technical support in conjunction with PRX to answer all your distribution questions. In cases of emergency or for use as an alternate distribution platform, we also offer an FTP (File Transfer Protocol), which is kept up to date with all of our series and specials. We keep you informed about our shows and help you promote them to your listeners: • Affiliates receive our quarterly Network Notebook with all our program offerings, and our regular online WFMT Radio Network Newsletter, with news updates, previews of upcoming shows and more. -

Stilles Meer 4K PRODUCTIONS Hamburg Opera | Length: 105 Min

Gioachino Rossini RichaRd StRauSS LA GAzzeTTA AriAdne Nicola Alaimo • Hasmik Torosyan • Vito Priante • Raffaella Lupinacci OTTORINO RESPIGHI Auf nAxos CHARLES GOUNOD sOile isOkOski ∙ sOphie kOch LA CAMPANA JOchen schmeckenBecher ∙ JOhan BO tha SOMMERSA FAUST ANGELO VILLARI · VALENTINA FARCAS · THOMAS GAZHELI · MARIA LUIGIA BORSI CONDUCTED BY DONATO RENZETTI · STAGED BY PIER FRANCESCO MAESTRINI TEATRO LIRICO DI CAGLIARI Orchester der Wiener staatsOper PIOTR BECZAŁA∙ILDAR ABDRAZAKOV Orchestra del Teatro Comunale di Bologna conducted by enrique Mazzola conducted by christian thielemann MARIA AGRESTA∙ALEXEY MARKOV∙TARA ERRAUGHT staged by Marco Carniti staged by sven-eric BechtOlf WIENER PHILHARMONIKER CONDUCTED BY ALEJO PÉREZ STAGED BY REINHARD VON DER THANNEN Wiener staatsOper GIUSEPPE VERDI SEMPEROPER DRESDEN RICHARD WAGNER GAETANO DONIZETTI CARLO COLOMBARAAIDA | ANITA RACHVELISHVILI | KRISTIN LEWIS | FABIO SARTORI CONDUCTED BY ZUBIN MEHTA | STAGED BY PETER STEIN LOHENGRIN LA FAVORITE DANIEL ELĪNA GARANČA∙MATTHEW POLENZANI BARENBOIM MARIUSZ KWIECIEŃ∙MIKA KARES THE COMPLETE SCHUBERT PIANO SONATAS ARRIGO BOITO RENÉ PAPE · JOSEPH CALLEJA · KRISTINE OPOLAIS · KARINE BABAJANYAN BAYERISCHES STAATSORCHESTER CONDUCTED BY OMER MEIR WELLBER Evelyn Georg Piotr Anna Tomasz STAGED BY ROLAND SCHWAB · BAYERISCHE STAATSOPER HERLITZIUS ZEPPENFELD BECZAŁA NETREBKO KONIECZNY STAATSKAPELLE DRESDEN CHRISTIAN THIELEMANN CONDUCTED BY KAREL MARK CHICHON STAGED BY AMÉLIE NIERMEYER BAYERISCHE STAATSOPER FESTIVAL VERDI PARMA GIUSEPPE VERDI GIACOMO PUCCINI GIUSEPPE -

Dayton Opera Artistic Director Thomas Bankston to Retire at the Conclusion of His 25Th Season with Dayton Opera in June 2021

Dayton Opera Artistic Director Thomas Bankston to Retire at the Conclusion of His 25th Season with Dayton Opera in June 2021 CONTACT: ANGELA WHITEHEAD Communications & Media Manager Dayton Performing Arts Alliance Phone 937-224-3521 x 1138 [email protected] DAYTON, OH (February 7, 2020) – The Dayton Performing Arts Alliance (DPAA) has announced today that Thomas Bankston, Artistic Director of Dayton Opera, will retire in June 2021, at the conclusion of the newly announced 2020–2021 Celebrate Season, Dayton Opera’s 60th anniversary season. “The coming together of three especially celebratory events in the 2020-21 season – Dayton Opera’s 60th anniversary, my 25th season, and the closing of that season with a world premiere opera production, Finding Wright – seemed like a fitting time at which to bring to a close my 41 year career in the professional opera business. Dayton Opera has been a huge part of my life and will always hold a special place in my heart. Especially all the wonderful friendships and associations I have made with artists, staff and volunteers that will make my retirement a truly bittersweet one,” said Tom Bankston. The 2020–2021 season will mark Bankston’s 25th season providing artistic leadership for Dayton Opera, the longest term of artistic leadership in the company’s history. In 1996, he began his work with the company, sharing his wide-ranging knowledge of the field of opera between Dayton Opera and Cincinnati Opera, the company where in 1982 he began his work as an opera administrator. At the start of the 2001–2002 season, he left Cincinnati Opera and assumed the position of Artistic Director for Dayton Opera on a full-time basis, and then was named General & Artistic Director of Dayton Opera in 2004. -

Metropolitan Opera 19-20 Season Press Release

Updated: November 12, 2019 New Productions of Porgy and Bess, Der Fliegende Holländer, and Wozzeck, and Met Premieres of Agrippina and Akhnaten Headline the Metropolitan Opera’s 2019–20 Season Yannick Nézet-Séguin, in his second season as Music Director, conducts the new William Kentridge production of Wozzeck, as well as two revivals, Met Orchestra concerts at Carnegie Hall, and a New Year’s Eve Puccini Gala starring Anna Netrebko Sunday matinee performances are offered for the first time From Roberto Alagna to Sonya Yoncheva, favorite Met singers return Debuting conductors are Karen Kamensek, Antonello Manacorda, and Vasily Petrenko; returning maestros include Valery Gergiev and Sir Simon Rattle New York, NY (February 20, 2019)—The Metropolitan Opera today announced its 2019–20 season, which opens on September 23 with a new production of the Gershwins’ classic American opera Porgy and Bess, last performed at the Met in 1990, starring Eric Owens and Angel Blue, directed by James Robinson and conducted by David Robertson. Philip Glass’s Akhnaten receives its Met premiere with Anthony Roth Costanzo as the title pharaoh and J’Nai Bridges as Nefertiti, in a celebrated staging by Phelim McDermott and conducted by Karen Kamensek in her Met debut. Acclaimed visual artist and stage director William Kentridge directs a new production of Berg’s Wozzeck, starring Peter Mattei and Elza van den Heever, and led by the Met’s Jeanette Lerman-Neubauer Music Director Yannick Nézet-Séguin. In another Met premiere, Sir David McVicar stages the black comedy of Handel’s Agrippina, starring Joyce DiDonato as the conniving empress with Harry Bicket on the podium. -

Il Trovatore Was Made Stage Director Possible by a Generous Gift from Paula Williams the Annenberg Foundation

ilGIUSEPPE VERDItrovatore conductor Opera in four parts Marco Armiliato Libretto by Salvadore Cammarano and production Sir David McVicar Leone Emanuele Bardare, based on the play El Trovador by Antonio García Gutierrez set designer Charles Edwards Tuesday, September 29, 2015 costume designer 7:30–10:15 PM Brigitte Reiffenstuel lighting designed by Jennifer Tipton choreographer Leah Hausman The production of Il Trovatore was made stage director possible by a generous gift from Paula Williams The Annenberg Foundation The revival of this production is made possible by a gift of the Estate of Francine Berry general manager Peter Gelb music director James Levine A co-production of the Metropolitan Opera, Lyric Opera of Chicago, and the San Francisco principal conductor Fabio Luisi Opera Association 2015–16 SEASON The 639th Metropolitan Opera performance of GIUSEPPE VERDI’S il trovatore conductor Marco Armiliato in order of vocal appearance ferr ando Štefan Kocán ines Maria Zifchak leonor a Anna Netrebko count di luna Dmitri Hvorostovsky manrico Yonghoon Lee a zucena Dolora Zajick a gypsy This performance Edward Albert is being broadcast live on Metropolitan a messenger Opera Radio on David Lowe SiriusXM channel 74 and streamed at ruiz metopera.org. Raúl Melo Tuesday, September 29, 2015, 7:30–10:15PM KEN HOWARD/METROPOLITAN OPERA A scene from Chorus Master Donald Palumbo Verdi’s Il Trovatore Musical Preparation Yelena Kurdina, J. David Jackson, Liora Maurer, Jonathan C. Kelly, and Bryan Wagorn Assistant Stage Director Daniel Rigazzi Italian Coach Loretta Di Franco Prompter Yelena Kurdina Assistant to the Costume Designer Anna Watkins Fight Director Thomas Schall Scenery, properties, and electrical props constructed and painted by Cardiff Theatrical Services and Metropolitan Opera Shops Costumes executed by Lyric Opera of Chicago Costume Shop and Metropolitan Opera Costume Department Wigs and Makeup executed by Metropolitan Opera Wig and Makeup Department Ms. -

RSTD OPERN Nov Dez 212X476 15.10.12 17:48 Seite 1

RSTD OPERN_Nov_Dez_212x476 15.10.12 17:48 Seite 1 Opernprogramm November 2012 November Franz Liszt Legende der heiligen Elisabeth 20.00 - 22.35 Hermann: Kolos Kováts, Sophie: Éva Farkas, Ludwig: Sándor Sólyom-Nagy, Elisabeth: Éva Marton, 1 Friedrich II. von Hohenstaufen: József Gregor, Ungarischer Magnat: István Gáti, Seneschal: István Gáti. Donnerstag Ungarische Nationalphilharmonie, Leitung: Árpád Joó, 1984. November Léo Delibes Lakmé 20.00 - 21.55 Nilakantha: Clifford Grant, Lakmé: Joan Sutherland, Mallika: Huguette Tourangeau, Hadji: Graeme Ewer, 3 Gerald: Henri Wilden, Frederick: John Pringle, Ellen: Isobel Buchanan. Samstag Australian Opera Chorus, Elizabethan Sydney Orchestra, Leitung: Richard Bonynge, 1976. November Bedrichˇ Smetana Die verkaufte Braut 20.00 - 22.25 Marenka: Dana Burešová, Jenik: Tomáš Juhás, Kecal: Jozef Benci, Vašek: Aleš Vorácek, 6 Mícha: Gustáv Belácek, Háta: Lucie Hilscherová, Krušina: Svatopluk Sem, Ludmila: Stanislava Jirku. Dienstag BBC Singers, BBC Symphony Orchestra, Leitung: Jirí Belohlávek, 2011. November Wolfgang Amadé Mozart Le nozze di Figaro 20.00 - 23.00 Almaviva: Tom Krause, Gräfin: Anna Tomowa-Sintow, Susanna: Ileana Cotrubas, Figaro: José van Dam, Cherubino: Frederica 8 von Stade, Bartolo: Jules Bastin, Marcellina: Jane Berbié, Basilio: Heinz Zednik, Don Curzio: Kurt Equiluz. Donnerstag Chor und Orchester der Wiener Staatsoper, Leitung: Herbert von Karajan, 1977. November Christoph Willibald Gluck Alceste 20.00 - 22.25 Admete: Paul Groves, Alceste: Anne Sofie von Otter, Oberpriester: Dietrich Henschel, Euandros: Yann Beuron, 10 Herakles: Dietrich Henschel, Herold: Ludovic Tézier, Orakel: Nicolas Testé, Apollo: Ludovic Tézier. Samstag Monteverdi Choir, English Baroque Soloists, Leitung: Sir John Eliot Gardiner, 1999. November Christoph Willibald Gluck Paride ed Elena 20.00 - 22.30 13 Paride: Magdalena Kožená, Elena: Susan Gritton, Amore: Carolyn Sampson, Pallade: Gillian Webster. -

Grand Finals

NATIONAL COUNCIL AUDITIONS grand finals conductor Metropolitan Opera Antony Walker National Council host Grand Finals Concert Deborah Voigt Sunday, March 13, 2016 guest artist 3:00 PM Eric Owens Metropolitan Opera Orchestra The Metropolitan Opera National Council is grateful to the Charles H. Dyson Endowment Fund for underwriting the Council’s Auditions Program. The 2016 Grand Finals Concert is dedicated to the memory of James S. Marcus. general manager Peter Gelb music director James Levine principal conductor Fabio Luisi 2015–16 SEASON NATIONAL COUNCIL AUDITIONS grand finals conductor Antony Walker host Deborah Voigt guest artist Eric Owens “Largo al factotum” from Il Barbiere di Siviglia (Rossini) Brian Vu, Baritone “Contro un cor” from Il Barbiere di Siviglia (Rossini) Emily D’Angelo, Mezzo-Soprano “Di Provenza il mar” from La Traviata (Verdi) Sol Jin, Baritone “Das war sehr gut, Mandryka” from Arabella (Strauss) Lauren Feider, Soprano “Bella siccome un angelo” from Don Pasquale (Donizetti) Today’s concert is Sean Michael Plumb, Baritone being recorded for “Ich baue ganz auf deine Stärke” from future broadcast Die Entführung aus dem Serail (Mozart) over many public Jonas Hacker, Tenor radio stations. Please check “Mein Sehnen, mein Wähnen” from Die Tote Stadt (Korngold) local listings. Theo Hoffman, Baritone Sunday, March 13, 2016, 3:00PM “I know a bank where the wild thyme blows” from A Midsummer Night’s Dream (Britten) Jakub Józef Orliński, Countertenor “Come scoglio” from Così fan tutte (Mozart) Yelena Dyachek, Soprano Intermission -

La Bohème Cast 2020 Biography

La Bohème Cast 2020 Biography (Vallo della Lucania, Italy) Italian Soprano Maria Agresta began her vocal studies at the Salerno Conservatory as a mezzo-soprano, later switching to soprano and studying with Raina Kabaivanska. After winning several international competitions she made her professional operatic debut in 2007. Engagements include Mimì and Micaëla (Carmen) for the Metropolitan Opera, New York, Suor Angelica for Liceu, Barcelona, Marguerite (Faust) for Salzburg Festival, Leonora (Il trovatore), Liù (Turandot), Donna Elvira (Don Giovanni) and Leonora (Oberto) for La Scala, Milan, Norma for Théâtre des Champs- Élysées and in Madrid, Turin and Tel Aviv, Mimì for Arena di Verona, Paris Opéra, Bavarian State Opera, Teatro Regio, Teatro di San Carlo, Naples, and Torre del Lago Festival, Elvira (I puritani) for Paris Opéra, Violetta (La traviata) for Berlin State Opera and Bavarian State Opera, Elena (I vespri siciliani) in Turin, Leonora (Il trovatore) for Palau de les Arts Reina Sofía, Valencia, Amelia (Simon Boccanegra) for Rome Opera, La Fenice, Venice, Dresden Semperoper and Berlin State Opera with Daniel Barenboim, Amalia (I masnadieri) for La Fenice and Julia (La Vestale) for Dresden Semperoper. Agresta performs widely in concert with such conductors as Barenboim, Nicola Luisotti, Michele Mariotti, Zubin Mehta, Carlo Montanaro, Riccardo Muti, Noseda and Christian Thielemann. Source: Royal Opera House (Brașov, Romania) Aurelia Florian was born in Romania where she has completed her musical studies (singing and piano), she studied at the Music faculty of the university of Transylvania in Brasov and specialized herself in belcanto singing in master classes with the Romanian soprano Mariana Nicolesco. At the Romanian Atheneum Bucharest (with the George Enescu Philharmonic Orchestra) she was highly acclaimed for singing the soprano part in Mahler’s IV symphony (under M° David Gimenez Carreras), and in 2009 she had a big success with the contemporary opera “Celan” written and conducted by Peter Ruzicka. -

Engage Your Mind in Today’S World

2018 GLOBAL ISSUES SARASOTA INSTITUTE OF LIFETIME LEARNING Engage Your Mind in Today’s World NORTH KOREA CHINA AFRICA MEXICO WINNERR Voted the Best Local Non-Profit 2017 for intellectually enriching the region www.sillsarasota.org Sarasota Program A Message from the President Pages M4-M5 MONDAY MUSIC SESSIONS Welcome to SILL’s 47th season! MUSIC MONDAYS This year we’re dedicating the entire Music Mondays series to the memory of our beloved 12 Lectures January 8 - March 26, 10:30 am June LeBell. June’s popular Music Mondays Church of the Palms, 3224 Bee Ridge Road series has been a favorite of Sarasota music Pages G4-G5 TUESDAY LECTURE SERIES lovers for many years. Ed Alley, June’s part- ner in life and music, will carry on with the GLOBAL ISSUES SERIES I program that he and June planned together 12 Lectures January 9 - March 27, 10:30 am for the 2018 season. In addition to his star- First United Methodist Church, 104 S. Pineapple Ave. ring role as June’s husband, Ed, a conductor, Pages G6-G7 WEDNESDAY LECTURE SERIES was manager of the New York Philharmonic and Associate Director of the Julliard Opera Center. For a detailed rundown of the musical treats GLOBAL ISSUES SERIES II coming up this season, check the Music Mondays program on the flip 12 Lectures January 10 - March 28, 10:30 am side of this brochure. First United Methodist Church, 104 S. Pineapple Ave. SILL’s Global Issues series was launched in 1972 by a group of Saraso- Pages G8-G9 THURSDAY LECTURE SERIES tans intent on providing stimulating, informative lectures on the critical issues of the day.