Chapter Outline Thinking Ahead 6 ASTRONOMICAL INSTRUMENTS

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Edwin Powell Hubble Papers: Finding Aid

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/tf7b69n8rd Online items available Edwin Powell Hubble Papers: Finding Aid Processed by Ronald S. Brashear, completed December 12, 1997; machine-readable finding aid created by Xiuzhi Zhou and updated by Diann Benti in June 2017. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens Manuscripts Department 1151 Oxford Road San Marino, California 91108 Phone: (626) 405-2191 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.huntington.org © 1998 The Huntington Library. All rights reserved. Edwin Powell Hubble Papers: mssHUB 1-1098 1 Finding Aid Overview of the Collection Title: Edwin Powell Hubble Papers Dates (inclusive): 1900-1989 Collection Number: mssHUB 1-1098 Creator: Hubble, Edwin, 1889-1953. Extent: 1300 pieces, plus ephemera in 34 boxes Repository: The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens. Manuscripts Department 1151 Oxford Road San Marino, California 91108 Phone: (626) 405-2191 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.huntington.org Abstract: This collection contains the papers of Edwin P. Hubble (1889-1953), an astronomer at the Mount Wilson Observatory near Pasadena, California. as well as the diaries and biographical memoirs of his wife, Grace Burke Hubble. Language: English. Access Open to qualified researchers by prior application through the Reader Services Department. For more information, contact Reader Services. Publication Rights The Huntington Library does not require that researchers request permission to quote from or publish images of this material, nor does it charge fees for such activities. The responsibility for identifying the copyright holder, if there is one, and obtaining necessary permissions rests with the researcher. Preferred Citation [Identification of item]. -

Telescopes and Binoculars

Continuing Education Course Approved by the American Board of Opticianry Telescopes and Binoculars National Academy of Opticianry 8401 Corporate Drive #605 Landover, MD 20785 800-229-4828 phone 301-577-3880 fax www.nao.org Copyright© 2015 by the National Academy of Opticianry. All rights reserved. No part of this text may be reproduced without permission in writing from the publisher. 2 National Academy of Opticianry PREFACE: This continuing education course was prepared under the auspices of the National Academy of Opticianry and is designed to be convenient, cost effective and practical for the Optician. The skills and knowledge required to practice the profession of Opticianry will continue to change in the future as advances in technology are applied to the eye care specialty. Higher rates of obsolescence will result in an increased tempo of change as well as knowledge to meet these changes. The National Academy of Opticianry recognizes the need to provide a Continuing Education Program for all Opticians. This course has been developed as a part of the overall program to enable Opticians to develop and improve their technical knowledge and skills in their chosen profession. The National Academy of Opticianry INSTRUCTIONS: Read and study the material. After you feel that you understand the material thoroughly take the test following the instructions given at the beginning of the test. Upon completion of the test, mail the answer sheet to the National Academy of Opticianry, 8401 Corporate Drive, Suite 605, Landover, Maryland 20785 or fax it to 301-577-3880. Be sure you complete the evaluation form on the answer sheet. -

Researchers Hunting Exoplanets with Superconducting Arrays

Cryocoolers, a Brief Overview .............................. 8 NASA Preps Four Telescope Missions .............. 37 Lake Shore Celebrates 50 Years ....................... 22 ICCRT Recap ..................................................... 38 Recovering Cold Energy and Waste Heat ............ 32 3-D Printing from Aqueous Materials .................. 40 Exoplanet Hunt with ADR-Cooled Superconducting Detector Arrays | 34 Volume 34 Number 3 Researchers Hunting Exoplanets with Superconducting Arrays The key to revealing the exoplanets tucked away around the universe may just be locked up in the advancement of Microwave Kinetic Inductance Detectors (MKIDs), an array of superconducting de- tectors made from platinum sillicide and housed in a cryostat at 100 mK. An astronomy team led by Dr. Benjamin Mazin at the University of California Santa Barbara is using MKID arrays for research on two telescopes, the Hale telescope at Palomar Observatory near San Diego and the Subaru telescope located at the Maunakea Observatory on Hawaii. Mazin began work on MKIDs nearly two decades ago while working under Dr. Jonas Zmuidzinas at Caltech, who co-pioneered the detectors for cosmic microwave background astronomy with Dr. Henry LeDuc at JPL. A look inside the DARKNESS cryostat. Image: Mazin Mazin has since adapted and ad- vanced the technology for the direct im- aging of exoplanets. With direct imaging, telescopes detect light from the planet itself, recording either the self-luminous thermal infrared light that young—and still hot—planets give off, or reflected light from a star that bounces off a planet and then towards the detector. Researchers have previously relied on indirect methods to search for exo- planets, including the radial velocity technique that looks at the spectrum of a star as it’s pushed and pulled by its planetary companions; and transit pho- tometry, where a dip in the brightness of a star is detected as planets cross in front The astronomy team working with Dr. -

The JWST/Nircam Coronagraph: Mask Design and Fabrication

The JWST/NIRCam coronagraph: mask design and fabrication John E. Krista, Kunjithapatham Balasubramaniana, Charles A. Beichmana, Pierre M. Echternacha, Joseph J. Greena, Kurt M. Liewera, Richard E. Mullera, Eugene Serabyna, Stuart B. Shaklana, John T. Traugera, Daniel W. Wilsona, Scott D. Hornerb, Yalan Maob, Stephen F. Somersteinb, Gopal Vasudevanb, Douglas M. Kellyc, Marcia J. Riekec aJet Propulsion Laboratory/California Institute of Technology, 4800 Oak Grove Drive, Pasasdena, CA, USA 91109; bLockheed Martin Advanced Technology Center, Palo Alto, CA, USA 94303; cUniversity of Arizona, Tucson, AZ, USA 85721 ABSTRACT The NIRCam instrument on the James Webb Space Telescope will provide coronagraphic imaging from λ=1-5 µm of high contrast sources such as extrasolar planets and circumstellar disks. A Lyot coronagraph with a variety of circular and wedge-shaped occulting masks and matching Lyot pupil stops will be implemented. The occulters approximate grayscale transmission profiles using halftone binary patterns comprising wavelength-sized metal dots on anti-reflection coated sapphire substrates. The mask patterns are being created in the Micro Devices Laboratory at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory using electron beam lithography. Samples of these occulters have been successfully evaluated in a coronagraphic testbed. In a separate process, the complex apertures that form the Lyot stops will be deposited onto optical wedges. The NIRCam coronagraph flight components are expected to be completed this year. Keywords: NIRCam, JWST, James Webb Space Telescope, coronagraph 1. INTRODUCTION 1.1 The planet/star contrast problem Observations of extrasolar planet formation (e.g. protoplanetary disks) and planetary systems are hampered by the large contrast differences between these targets and their much brighter stars. -

Large Telescopes and Why We Need Them Transcript

Large telescopes and why we need them Transcript Date: Wednesday, 9 May 2012 - 1:00PM Location: Museum of London 9 May 2012 Large Telescopes And Why we Need Them Professor Carolin Crawford Astronomy is a comparatively passive science, in that we can’t engage in laboratory experiments to investigate how the Universe works. To study any cosmic object outside of our Solar System, we can only work with the light it emits that happens to fall on Earth. How much we can interpret and understand about the Universe around us depends on how well we can collect and analyse that light. This talk is about the first part of that problem: how we improve the collection of light. The key problem for astronomers is that all stars, nebulae and galaxies are so very far away that they appear both very small, and very faint - some so much so that they can’t be seen without the help of a telescope. Its role is simply to collect more light than the unaided eye can, making astronomical sources appear both bigger and brighter, or even just to make most of them visible in the first place. A new generation of electronic detectors have made observations with the eye redundant. We now have cameras to record the images directly, or once it has been split into its constituent wavelengths by spectrographs. Even though there are a whole host of ingenious and complex instruments that enable us to record and analyse the light, they are still only able to work with the light they receive in the first place. -

Demonstration of Vortex Coronagraph Concepts for On-Axis Telescopes on the Palomar Stellar Double Coronagraph

Demonstration of vortex coronagraph concepts for on-axis telescopes on the Palomar Stellar Double Coronagraph Dimitri Maweta, Chris Sheltonb, James Wallaceb, Michael Bottomc, Jonas Kuhnb, Bertrand Mennessonb, Rick Burrussb, Randy Bartosb, Laurent Pueyod, Alexis Carlottie, and Eugene Serabynb aEuropean Southern Observatory, Alonso de C´ordova 3107, Vitacura, Casilla 19001, Chile; bJet Propulsion Laboratory, California Institute of Technology, Pasadena, CA 91109, USA; cCalifornia Institute of Technology, Pasadena, CA 91106, USA; dSpace Telescope Science Institute, 3700 San Martin Drive, Baltimore, MD 21218, USA; eInstitut de Plan´etologieet d'Astrophysique de Grenoble (IPAG), University Joseph Fourier, CNRS, BP 53, 38041, Grenoble, France; ABSTRACT Here we present preliminary results of the integration of two recently proposed vortex coronagraph (VC) concepts for on-axis telescopes on the Stellar Double Coronagraph (SDC) bench behind PALM-3000, the extreme adaptive optics system of the 200-inch Hale telescope of Palomar observatory. The multi-stage vortex coronagraph (MSVC) uses the ability of the vortex to move light in and out of apertures through multiple VC in series to restore the nominal attenuation capability of the charge 2 vortex regardless of the aperture obscurations. The ring-apodized vortex coronagraph (RAVC) is a one-stage apodizer exploiting the VC Lyot-plane amplitude distribution in order to perfectly null the diffraction from any central obscuration size, and for any vortex topological charge. The RAVC is thus a simple concept that makes the VC immune to diffraction effects of the secondary mirror. It combines a vortex phase mask in the image plane with a single pupil-based amplitude ring apodizer, tailor-made to exploit the unique convolution properties of the VC at the Lyot-stop plane. -

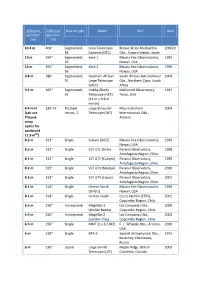

Effective Aperture 3.6–4.9 M) 4.7 M 186″ Segmented, MMT (6×1.8 M) F

Effective Effective Mirror type Name Site Built aperture aperture (m) (in) 10.4 m 409″ Segmented, Gran Telescopio Roque de los Muchachos 2006/9 36 Canarias (GTC) Obs., Canary Islands, Spain 10 m 394″ Segmented, Keck 1 Mauna Kea Observatories, 1993 36 Hawaii, USA 10 m 394″ Segmented, Keck 2 Mauna Kea Observatories, 1996 36 Hawaii, USA 9.8 m 386″ Segmented, Southern African South African Astronomical 2005 91 Large Telescope Obs., Northern Cape, South (SALT) Africa 9.2 m 362″ Segmented, Hobby-Eberly McDonald Observatory, 1997 91 Telescope (HET) Texas, USA (11 m × 9.8 m mirror) 8.4 m×2 330″×2 Multiple Large Binocular Mount Graham 2004 (can use mirror, 2 Telescope (LBT) Internationals Obs., Phased- Arizona array optics for combined 11.9 m[2]) 8.2 m 323″ Single Subaru (JNLT) Mauna Kea Observatories, 1999 Hawaii, USA 8.2 m 323″ Single VLT UT1 (Antu) Paranal Observatory, 1998 Antofagasta Region, Chile 8.2 m 323″ Single VLT UT2 (Kueyen) Paranal Observatory, 1999 Antofagasta Region, Chile 8.2 m 323″ Single VLT UT3 (Melipal) Paranal Observatory, 2000 Antofagasta Region, Chile 8.2 m 323″ Single VLT UT4 (Yepun) Paranal Observatory, 2001 Antofagasta Region, Chile 8.1 m 318″ Single Gemini North Mauna Kea Observatories, 1999 (Gillett) Hawaii, USA 8.1 m 318″ Single Gemini South Cerro Pachón (CTIO), 2001 Coquimbo Region, Chile 6.5 m 256″ Honeycomb Magellan 1 Las Campanas Obs., 2000 (Walter Baade) Coquimbo Region, Chile 6.5 m 256″ Honeycomb Magellan 2 Las Campanas Obs., 2002 (Landon Clay) Coquimbo Region, Chile 6.5 m 256″ Single MMT (1 x 6.5 M1) F. -

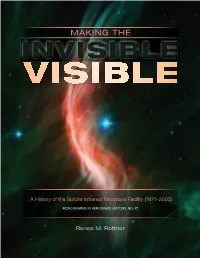

Making the Invisible Visible: a History of the Spitzer Infrared Telescope Facility (1971–2003)/ by Renee M

MAKING THE INVISIBLE A History of the Spitzer Infrared Telescope Facility (1971–2003) MONOGRAPHS IN AEROSPACE HISTORY, NO. 47 Renee M. Rottner MAKING THE INVISIBLE VISIBLE A History of the Spitzer Infrared Telescope Facility (1971–2003) MONOGRAPHS IN AEROSPACE HISTORY, NO. 47 Renee M. Rottner National Aeronautics and Space Administration Office of Communications NASA History Division Washington, DC 20546 NASA SP-2017-4547 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Rottner, Renee M., 1967– Title: Making the invisible visible: a history of the Spitzer Infrared Telescope Facility (1971–2003)/ by Renee M. Rottner. Other titles: History of the Spitzer Infrared Telescope Facility (1971–2003) Description: | Series: Monographs in aerospace history; #47 | Series: NASA SP; 2017-4547 | Includes bibliographical references. Identifiers: LCCN 2012013847 Subjects: LCSH: Spitzer Space Telescope (Spacecraft) | Infrared astronomy. | Orbiting astronomical observatories. | Space telescopes. Classification: LCC QB470 .R68 2012 | DDC 522/.2919—dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2012013847 ON THE COVER Front: Giant star Zeta Ophiuchi and its effects on the surrounding dust clouds Back (top left to bottom right): Orion, the Whirlpool Galaxy, galaxy NGC 1292, RCW 49 nebula, the center of the Milky Way Galaxy, “yellow balls” in the W33 Star forming region, Helix Nebula, spiral galaxy NGC 2841 This publication is available as a free download at http://www.nasa.gov/ebooks. ISBN 9781626830363 90000 > 9 781626 830363 Contents v Acknowledgments -

Frontiers in Space: Official Publication of the Mount Wilson and Palomar

Mount W ilson Observatory is situated near the summit of a 5,713-foot peak of the San Gabriel range. Astronomical instru ments at the Observatory comprise three solar telescopes, the largest of which is the 150-foot tower visible at the left, and two star telescopes, the 60-inch reflector and the well-known 100-inch Hooker reflector. Palomar Observatory is built on a 5,600-foot-high plateau near the top of Palomar Mountain. Its in struments, all stellar telescopes, are the 18-inch and 48-inch MOUNT WILSON LA CANADA schmidt-type wide-angle astro ~. IDIVI DED ~GY nomical cameras and the 200-inch PASADENA --.,~ CLAREMONT Hale reflector. / , ~ ...........----- lOS ANGElB • ....... FRH'h~t ONTARIOI ~ ""'""·~.. !G U.KE H(NSHAW SAN DIEGO The California Institute of Technology ASTROPHYSICS LIBRARY Mount Wilson and Palomar Observatories The Mount Wilson and Palomar Observa tories are situated on two Southern California mountains: the one, Mount Wilson, about 30 miles by road north of Pasadena; and the other, Palomar Mountain, about 130 miles to the southeast. The two observatories, together with the adnz.inistrative and research centers in Pasa dena, are operated jointly by the Carnegie Institution of Washington and the California Institute of Technology in a broad, coordi nated program of astronomical research. It is because the two observatories take part in this one unified program that both are included in this one hook. It would be impossible to talk about the past, present, or fuh~re of one without refere'nce to the other. Both observatories are largely the result of the lifework of one man: the astronomer George Ellery Hale. -

The Big Eye Vol 4 No 2

Celebrate the International Year of Astronomy In celebration of the 400th anniversary of Galileo’s first astronomical observations, the International Astronomical Union and the United Nations have designated 2009 as the International Year of Astronomy (IYA). There are many ways to celebrate the IYA. The best way is to get outside under the night sky. Even better, spend some time looking through a telescope. The Friends of Palomar will have at least six observing nights in 2009 (details are coming soon), but if that isn’t enough, seek out your local astronomy club and look to see when they are holding star parties. There will be lots of star parties in conjunction with the IYA’s 100 Hours of Astronomy (100HA) event to be held April 2 – 5. It is a four-day, round the world star party. Visit their website at http://www.100hoursofastronomy.org/ to find local events. Embedded within the 100HA event is Around the World in 80 Telescopes. It is a 24-hour live webcast event that will take place from the control rooms of research telescopes located around the globe. Included in the mix will be Palomar Observatory. Most people have no idea what happens during the night at a research observatory. The expectation is that astronomers are looking through telescopes – a concept that is 100 years out of date. The Around the World in 80 Telescopes event will give people an inside look to what really happens by letting them take their own trip to observatories located across the globe (and in space too). -

Brown Dwarf Seen Jupiter - an Abundance of Methane

(like Markarian 421, known to emit astrophysics could enter a new but too small and cool to shine like a high-energy gamma rays), it would exciting phase. star. At least 250,000 times dimmer give important insight into the mecha than Earth's Sun, the long-sought nisms of acceleration of the highest Lars Bergstrom (Stockholm and brown dwarf is the faintest object energy cosmic rays. Uppsala Universities) and Hector ever seen orbiting another star. There is also the possibility of an Rubinstein (Uppsala University) The infrared spectroscopic isotropic, "diffuse" high-energy observations of GL229B, made with neutrino component arising from the Palomar's 200-inch Hale telescope, result of all AGNs in the Universe. show that the dwarf has the same Although rate estimates are beset spectral 'fingerprint' as the planet with large uncertainties, AMANDA Brown dwarf seen Jupiter - an abundance of methane. could detect some tens of events per Methane is not seen in ordinary year, based on the measured gamma stronomers have made the first stars, but is present in Jupiter and ray flux. A unambiguous sighting of a other giant gaseous planets in our High-energy neutrinos may also 'brown dwarf' star. Solar System. give clues to the dark matter mystery. The evidence consists of an image The Hubble data obtained and Perhaps the most promising from the 60-inch Mount Palomar analysed so far show the object is far candidate for the dark matter in observatory and a spectrum from dimmer, cooler (no more than 750 galactic halos is the lightest the 200-inch Hale telescope on degrees) and less massive than supersymmetric particle. -

Mt. Palomar: Nebula Seeker Conceived Over 100 Years Ago, Palomar Observatory, Located on Mt

Mt. Palomar: Nebula Seeker Conceived over 100 years ago, Palomar Observatory, located on Mt. Palomar in northern San Diego, California is owned and run by Caltech. The Observatory has three active telescopes and partners with others in the U.S.A. and internationally. George Ellery Hale was responsible for its development. At that time, he was a graduate of MIT and founder of Caltech in Pasadena, California. The Rockefeller Foundation provided a grant for $6 million in 1928 to eventually have a 200‐inch reflecting telescope on site. Hale died in 1938, but his work was in building the world’s largest telescopes four times between 1897 and 1917. His passion for searching out into space made the grant possible. Hale’s technical skills made history and a new product called Pyrex by the Corning Glass Works, Corning NY. Through many stages, failures and success, in 1936, the 200‐inch optical glass was transported to Pasadena. It weighed approximately 4.5 tons and it would take 13 years to grind and configure the glass for the mirror telescope. During the early 1930s, Hale originally thought the 200‐inch telescope would be used at the Mt. Wilson Observatory near Los Angeles. However, light degradation in that city caused a new site to be considered. In 1934, Caltech purchased 120 acres of land including the top of the mountain. The cost for the land was $12,000. Construction began in 1936, but because of its location, electricity had to come from a generator built on site. On April 11, 1939 the dome and telescope were completed, but without its mirror.