Large Telescopes and Why We Need Them Transcript

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Edwin Powell Hubble Papers: Finding Aid

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/tf7b69n8rd Online items available Edwin Powell Hubble Papers: Finding Aid Processed by Ronald S. Brashear, completed December 12, 1997; machine-readable finding aid created by Xiuzhi Zhou and updated by Diann Benti in June 2017. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens Manuscripts Department 1151 Oxford Road San Marino, California 91108 Phone: (626) 405-2191 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.huntington.org © 1998 The Huntington Library. All rights reserved. Edwin Powell Hubble Papers: mssHUB 1-1098 1 Finding Aid Overview of the Collection Title: Edwin Powell Hubble Papers Dates (inclusive): 1900-1989 Collection Number: mssHUB 1-1098 Creator: Hubble, Edwin, 1889-1953. Extent: 1300 pieces, plus ephemera in 34 boxes Repository: The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens. Manuscripts Department 1151 Oxford Road San Marino, California 91108 Phone: (626) 405-2191 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.huntington.org Abstract: This collection contains the papers of Edwin P. Hubble (1889-1953), an astronomer at the Mount Wilson Observatory near Pasadena, California. as well as the diaries and biographical memoirs of his wife, Grace Burke Hubble. Language: English. Access Open to qualified researchers by prior application through the Reader Services Department. For more information, contact Reader Services. Publication Rights The Huntington Library does not require that researchers request permission to quote from or publish images of this material, nor does it charge fees for such activities. The responsibility for identifying the copyright holder, if there is one, and obtaining necessary permissions rests with the researcher. Preferred Citation [Identification of item]. -

Telescopes and Binoculars

Continuing Education Course Approved by the American Board of Opticianry Telescopes and Binoculars National Academy of Opticianry 8401 Corporate Drive #605 Landover, MD 20785 800-229-4828 phone 301-577-3880 fax www.nao.org Copyright© 2015 by the National Academy of Opticianry. All rights reserved. No part of this text may be reproduced without permission in writing from the publisher. 2 National Academy of Opticianry PREFACE: This continuing education course was prepared under the auspices of the National Academy of Opticianry and is designed to be convenient, cost effective and practical for the Optician. The skills and knowledge required to practice the profession of Opticianry will continue to change in the future as advances in technology are applied to the eye care specialty. Higher rates of obsolescence will result in an increased tempo of change as well as knowledge to meet these changes. The National Academy of Opticianry recognizes the need to provide a Continuing Education Program for all Opticians. This course has been developed as a part of the overall program to enable Opticians to develop and improve their technical knowledge and skills in their chosen profession. The National Academy of Opticianry INSTRUCTIONS: Read and study the material. After you feel that you understand the material thoroughly take the test following the instructions given at the beginning of the test. Upon completion of the test, mail the answer sheet to the National Academy of Opticianry, 8401 Corporate Drive, Suite 605, Landover, Maryland 20785 or fax it to 301-577-3880. Be sure you complete the evaluation form on the answer sheet. -

Researchers Hunting Exoplanets with Superconducting Arrays

Cryocoolers, a Brief Overview .............................. 8 NASA Preps Four Telescope Missions .............. 37 Lake Shore Celebrates 50 Years ....................... 22 ICCRT Recap ..................................................... 38 Recovering Cold Energy and Waste Heat ............ 32 3-D Printing from Aqueous Materials .................. 40 Exoplanet Hunt with ADR-Cooled Superconducting Detector Arrays | 34 Volume 34 Number 3 Researchers Hunting Exoplanets with Superconducting Arrays The key to revealing the exoplanets tucked away around the universe may just be locked up in the advancement of Microwave Kinetic Inductance Detectors (MKIDs), an array of superconducting de- tectors made from platinum sillicide and housed in a cryostat at 100 mK. An astronomy team led by Dr. Benjamin Mazin at the University of California Santa Barbara is using MKID arrays for research on two telescopes, the Hale telescope at Palomar Observatory near San Diego and the Subaru telescope located at the Maunakea Observatory on Hawaii. Mazin began work on MKIDs nearly two decades ago while working under Dr. Jonas Zmuidzinas at Caltech, who co-pioneered the detectors for cosmic microwave background astronomy with Dr. Henry LeDuc at JPL. A look inside the DARKNESS cryostat. Image: Mazin Mazin has since adapted and ad- vanced the technology for the direct im- aging of exoplanets. With direct imaging, telescopes detect light from the planet itself, recording either the self-luminous thermal infrared light that young—and still hot—planets give off, or reflected light from a star that bounces off a planet and then towards the detector. Researchers have previously relied on indirect methods to search for exo- planets, including the radial velocity technique that looks at the spectrum of a star as it’s pushed and pulled by its planetary companions; and transit pho- tometry, where a dip in the brightness of a star is detected as planets cross in front The astronomy team working with Dr. -

The JWST/Nircam Coronagraph: Mask Design and Fabrication

The JWST/NIRCam coronagraph: mask design and fabrication John E. Krista, Kunjithapatham Balasubramaniana, Charles A. Beichmana, Pierre M. Echternacha, Joseph J. Greena, Kurt M. Liewera, Richard E. Mullera, Eugene Serabyna, Stuart B. Shaklana, John T. Traugera, Daniel W. Wilsona, Scott D. Hornerb, Yalan Maob, Stephen F. Somersteinb, Gopal Vasudevanb, Douglas M. Kellyc, Marcia J. Riekec aJet Propulsion Laboratory/California Institute of Technology, 4800 Oak Grove Drive, Pasasdena, CA, USA 91109; bLockheed Martin Advanced Technology Center, Palo Alto, CA, USA 94303; cUniversity of Arizona, Tucson, AZ, USA 85721 ABSTRACT The NIRCam instrument on the James Webb Space Telescope will provide coronagraphic imaging from λ=1-5 µm of high contrast sources such as extrasolar planets and circumstellar disks. A Lyot coronagraph with a variety of circular and wedge-shaped occulting masks and matching Lyot pupil stops will be implemented. The occulters approximate grayscale transmission profiles using halftone binary patterns comprising wavelength-sized metal dots on anti-reflection coated sapphire substrates. The mask patterns are being created in the Micro Devices Laboratory at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory using electron beam lithography. Samples of these occulters have been successfully evaluated in a coronagraphic testbed. In a separate process, the complex apertures that form the Lyot stops will be deposited onto optical wedges. The NIRCam coronagraph flight components are expected to be completed this year. Keywords: NIRCam, JWST, James Webb Space Telescope, coronagraph 1. INTRODUCTION 1.1 The planet/star contrast problem Observations of extrasolar planet formation (e.g. protoplanetary disks) and planetary systems are hampered by the large contrast differences between these targets and their much brighter stars. -

Nova Report 2006-2007

NOVA REPORTNOVA 2006 - 2007 NOVA REPORT 2006-2007 Illustration on the front cover The cover image shows a composite image of the supernova remnant Cassiopeia A (Cas A). This object is the brightest radio source in the sky, and has been created by a supernova explosion about 330 year ago. The star itself had a mass of around 20 times the mass of the sun, but by the time it exploded it must have lost most of the outer layers. The red and green colors in the image are obtained from a million second observation of Cas A with the Chandra X-ray Observatory. The blue image is obtained with the Very Large Array at a wavelength of 21.7 cm. The emission is caused by very high energy electrons swirling around in a magnetic field. The red image is based on the ratio of line emission of Si XIII over Mg XI, which brings out the bi-polar, jet-like, structure. The green image is the Si XIII line emission itself, showing that most X-ray emission comes from a shell of stellar debris. Faintly visible in green in the center is a point-like source, which is presumably the neutron star, created just prior to the supernova explosion. Image credits: Creation/compilation: Jacco Vink. The data were obtained from: NASA Chandra X-ray observatory and Very Large Array (downloaded from Astronomy Digital Image Library http://adil.ncsa.uiuc. edu). Related scientific publications: Hwang, Vink, et al., 2004, Astrophys. J. 615, L117; Helder and Vink, 2008, Astrophys. J. in press. -

Demonstration of Vortex Coronagraph Concepts for On-Axis Telescopes on the Palomar Stellar Double Coronagraph

Demonstration of vortex coronagraph concepts for on-axis telescopes on the Palomar Stellar Double Coronagraph Dimitri Maweta, Chris Sheltonb, James Wallaceb, Michael Bottomc, Jonas Kuhnb, Bertrand Mennessonb, Rick Burrussb, Randy Bartosb, Laurent Pueyod, Alexis Carlottie, and Eugene Serabynb aEuropean Southern Observatory, Alonso de C´ordova 3107, Vitacura, Casilla 19001, Chile; bJet Propulsion Laboratory, California Institute of Technology, Pasadena, CA 91109, USA; cCalifornia Institute of Technology, Pasadena, CA 91106, USA; dSpace Telescope Science Institute, 3700 San Martin Drive, Baltimore, MD 21218, USA; eInstitut de Plan´etologieet d'Astrophysique de Grenoble (IPAG), University Joseph Fourier, CNRS, BP 53, 38041, Grenoble, France; ABSTRACT Here we present preliminary results of the integration of two recently proposed vortex coronagraph (VC) concepts for on-axis telescopes on the Stellar Double Coronagraph (SDC) bench behind PALM-3000, the extreme adaptive optics system of the 200-inch Hale telescope of Palomar observatory. The multi-stage vortex coronagraph (MSVC) uses the ability of the vortex to move light in and out of apertures through multiple VC in series to restore the nominal attenuation capability of the charge 2 vortex regardless of the aperture obscurations. The ring-apodized vortex coronagraph (RAVC) is a one-stage apodizer exploiting the VC Lyot-plane amplitude distribution in order to perfectly null the diffraction from any central obscuration size, and for any vortex topological charge. The RAVC is thus a simple concept that makes the VC immune to diffraction effects of the secondary mirror. It combines a vortex phase mask in the image plane with a single pupil-based amplitude ring apodizer, tailor-made to exploit the unique convolution properties of the VC at the Lyot-stop plane. -

The GLENDAMA Database

Technical Report & User's Guide The GLENDAMA Database Luis J. Goicoechea, Vyacheslav N. Shalyapin? and Rodrigo Gil-Merino Universidad de Cantabria, Santander, Spain ABSTRACT This is the first version (v1) of the Gravitational LENses and DArk MAtter (GLENDAMA) database accessible at http://grupos.unican.es/glendama/database The new database contains more than 6000 ready-to-use (processed) astronomical frames corresponding to 15 objects that fall into three classes: (1) lensed QSO (8 objects), (2) binary QSO (3 objects), and (3) accretion-dominated radio-loud QSO (4 objects). Data are also divided into two categories: freely available and available upon request. The second category includes observations related to our yet unpublished analyses. Although this v1 of the GLENDAMA archive incorporates an X-ray monitoring campaign for a lensed QSO in 2010, the rest of frames (imaging, polarimetry and spectroscopy) were taken with NUV, visible and NIR facilities over the period 1999−2014. The monitorings and follow-up observations of lensed QSOs are key tools for discussing the accretion flow in distant QSOs, the redshift and structure of intervening (lensing) galaxies, and the physical properties of the Universe as a whole. Subject headings: astronomical databases | gravitational lensing: strong and micro | quasars: general | quasars: supermassive black holes | quasars: ac- cretion | galaxies: general | galaxies: distances and redshifts | galaxies: halos arXiv:1505.04317v2 [astro-ph.IM] 19 May 2015 | cosmological parameters ?permanent address: Institute for Radiophysics and Electronics, Kharkov, Ukraine { 2 { 1. Target objects and facilities At present, the Gravitational LENses and DArk MAtter (GLENDAMA) project at the Universidad de Cantabria (UC) is conducting a programme of observation of eight lensed QSOs with facilities at the European Northern Observatory (ENO). -

9. Instruments and Techniques (Instruments Et Techniques)

9. INSTRUMENTS AND TECHNIQUES (INSTRUMENTS ET TECHNIQUES) PRESIDENT: E.H. Richardson VICE-PRESIDENT: W. C. Livingston ORGANIZING COMMITTEE: T. Bolton, W. B. Burton, P. Connes, J. Davis, J. L. Heudier, I. M. Kopylov, A. Labeyrie, D. McMullan, A. B. Meinel, N. N. Mikhel'son, J. Ring, J. Rosch, N. Steshenko, G.A.H. Walker, M. F. Walker. I. MEETING AT THE 6 METRE TELESCOPE The major activity organized by Commission 9 was IAU Colloquium 67, Instrumentation for Large Telescopes, held 8-10 Sept., 1981, on a portion of the observing floor of the 6 metre telescope of the Special Astrophysical Observatory, USSR. The cooling coils in the floor were turned off and a rug laid. The enormous BTA (Bolshoi Altazimuth Telescope) provided a spectacular back drop to the 88 participants. Between sessions, the particpants were shown every detail of the telescope by its Chief Designer, Dr. B. K. Ioannisiani, and SAO staff. Night observations continued: speckle interferometry. The Proceedings, edited by C. M. Humphries, and consisting of some 40 titles and three photographs at the BTA, will be published by Reidel as "Instrumentation for Astronomy with Large Optical Telescopes." There are four sections. 1) Telescopes (existing, e.g. 6 metre, MMT and CFHT; under construction, e.g. 4.2 metre Herschel and Iraqi 3.5 metre; and planned, e.g. 7.6 metre Texas and USSR 6 metre polar); 2) Spectrographs (including multi-object, wide field, and with and without slit); 3) Interferometers; and 4) Detectors. The smallest telescope described, 5 cm, is located at the most extreme site, the South Pole, and is used to measure solar oscillations by the Observatoire de Nice. -

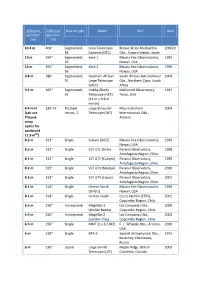

Effective Aperture 3.6–4.9 M) 4.7 M 186″ Segmented, MMT (6×1.8 M) F

Effective Effective Mirror type Name Site Built aperture aperture (m) (in) 10.4 m 409″ Segmented, Gran Telescopio Roque de los Muchachos 2006/9 36 Canarias (GTC) Obs., Canary Islands, Spain 10 m 394″ Segmented, Keck 1 Mauna Kea Observatories, 1993 36 Hawaii, USA 10 m 394″ Segmented, Keck 2 Mauna Kea Observatories, 1996 36 Hawaii, USA 9.8 m 386″ Segmented, Southern African South African Astronomical 2005 91 Large Telescope Obs., Northern Cape, South (SALT) Africa 9.2 m 362″ Segmented, Hobby-Eberly McDonald Observatory, 1997 91 Telescope (HET) Texas, USA (11 m × 9.8 m mirror) 8.4 m×2 330″×2 Multiple Large Binocular Mount Graham 2004 (can use mirror, 2 Telescope (LBT) Internationals Obs., Phased- Arizona array optics for combined 11.9 m[2]) 8.2 m 323″ Single Subaru (JNLT) Mauna Kea Observatories, 1999 Hawaii, USA 8.2 m 323″ Single VLT UT1 (Antu) Paranal Observatory, 1998 Antofagasta Region, Chile 8.2 m 323″ Single VLT UT2 (Kueyen) Paranal Observatory, 1999 Antofagasta Region, Chile 8.2 m 323″ Single VLT UT3 (Melipal) Paranal Observatory, 2000 Antofagasta Region, Chile 8.2 m 323″ Single VLT UT4 (Yepun) Paranal Observatory, 2001 Antofagasta Region, Chile 8.1 m 318″ Single Gemini North Mauna Kea Observatories, 1999 (Gillett) Hawaii, USA 8.1 m 318″ Single Gemini South Cerro Pachón (CTIO), 2001 Coquimbo Region, Chile 6.5 m 256″ Honeycomb Magellan 1 Las Campanas Obs., 2000 (Walter Baade) Coquimbo Region, Chile 6.5 m 256″ Honeycomb Magellan 2 Las Campanas Obs., 2002 (Landon Clay) Coquimbo Region, Chile 6.5 m 256″ Single MMT (1 x 6.5 M1) F. -

From the Director

The Official Publication of the Amateur Astronomers Association of Princeton Director Treasurer Program Chairman John Miller Michael Mitrano Ludy D’Angelo (609) 252-1223 609-737-6518 (609) 882-9336 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Assistant Director Secretary Editors John Church Larry Kane Bryan Hubbard and Ira Polans (609) 799-0723 (609) 276-1456 (732) 469-7698 and (609) 448-8644 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Volume 37 Midsummer 2008 Number 7 From the Director one point, a twenty foot limousine pulled up to the curb, and four occupants interrupted their evening to take a look through several Summer time…and the observin’s easy. Perhaps if Gershwin was scopes. To heck with the theatre – this was a better show! an astronomer, that’s how the tune would have been written. Both astronomers and the public were thrilled with the success of this Have you taken advantage of the balmy weather and occasional experiment, with an estimated hundred or more locals learning about clear night to get reacquainted with the July sky? astronomy, engaging questions and discovering the Moon, Jupiter and Saturn and Mars (having caught up to Saturn and lying very close binaries through two refractors and one Newtonian scope. as this is written), are far to the west as evening sets in. Sorry to A meeting to discuss plans for the AAAP 2008 – 2009 season is see the Ringed Planet leave for the evening season. Replacing scheduled for Tuesday, August 5th at 7:30PM. As of this writing, the him is his grand neighbor Jupiter, now better positioned earlier in location is uncertain due to Peyton Hall renovation. -

(68346) 2001 KZ66 from Combined Radar and Optical Observations

MNRAS 000,1–13 (2021) Preprint 1 September 2021 Compiled using MNRAS LATEX style file v3.0 Detection of the YORP Effect on the contact-binary (68346) 2001 KZ66 from combined radar and optical observations Tarik J. Zegmott,1¢ S. C. Lowry,1 A. Rożek,1,2 B. Rozitis,3 M. C. Nolan,4 E. S. Howell,4 S. F. Green,3 C. Snodgrass,2,3 A. Fitzsimmons,5 and P. R. Weissman6 1Centre for Astrophysics and Planetary Science, University of Kent, Canterbury, CT2 7NH, UK 2Institute for Astronomy, University of Edinburgh, Royal Observatory, Edinburgh, EH9 3HJ, UK 3Planetary and Space Sciences, School of Physical Sciences, The Open University, Milton Keynes, MK7 6AA, UK 4Lunar and Planetary Laboratory, University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ 85721, USA 5Astrophysics Research Centre, Queens University Belfast, Belfast, BT7 1NN, UK 6Planetary Sciences Institute, Tucson, AZ 85719, USA Accepted XXX. Received YYY; in original form ZZZ ABSTRACT The YORP effect is a small thermal-radiation torque experienced by small asteroids, and is considered to be crucial in their physical and dynamical evolution. It is important to understand this effect by providing measurements of YORP for a range of asteroid types to facilitate the development of a theoretical framework. We are conducting a long-term observational study on a selection of near-Earth asteroids to support this. We focus here on (68346) 2001 KZ66, for which we obtained both optical and radar observations spanning a decade. This allowed us to perform a comprehensive analysis of the asteroid’s rotational evolution. Furthermore, radar observations from the Arecibo Observatory enabled us to generate a detailed shape model. -

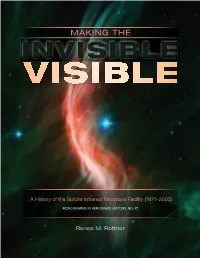

Making the Invisible Visible: a History of the Spitzer Infrared Telescope Facility (1971–2003)/ by Renee M

MAKING THE INVISIBLE A History of the Spitzer Infrared Telescope Facility (1971–2003) MONOGRAPHS IN AEROSPACE HISTORY, NO. 47 Renee M. Rottner MAKING THE INVISIBLE VISIBLE A History of the Spitzer Infrared Telescope Facility (1971–2003) MONOGRAPHS IN AEROSPACE HISTORY, NO. 47 Renee M. Rottner National Aeronautics and Space Administration Office of Communications NASA History Division Washington, DC 20546 NASA SP-2017-4547 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Rottner, Renee M., 1967– Title: Making the invisible visible: a history of the Spitzer Infrared Telescope Facility (1971–2003)/ by Renee M. Rottner. Other titles: History of the Spitzer Infrared Telescope Facility (1971–2003) Description: | Series: Monographs in aerospace history; #47 | Series: NASA SP; 2017-4547 | Includes bibliographical references. Identifiers: LCCN 2012013847 Subjects: LCSH: Spitzer Space Telescope (Spacecraft) | Infrared astronomy. | Orbiting astronomical observatories. | Space telescopes. Classification: LCC QB470 .R68 2012 | DDC 522/.2919—dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2012013847 ON THE COVER Front: Giant star Zeta Ophiuchi and its effects on the surrounding dust clouds Back (top left to bottom right): Orion, the Whirlpool Galaxy, galaxy NGC 1292, RCW 49 nebula, the center of the Milky Way Galaxy, “yellow balls” in the W33 Star forming region, Helix Nebula, spiral galaxy NGC 2841 This publication is available as a free download at http://www.nasa.gov/ebooks. ISBN 9781626830363 90000 > 9 781626 830363 Contents v Acknowledgments