Lahor and Technology in the Book Trades

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

IBM Selectric IT, with Manual, Ribbon, and Correction Tape

BART Q2B2 No. 1-2 Typewriters. No.1 Manual typewriter: Remington, 1965 with library keyboard. 23 x 36 x 49 em. No. 2 Electric typewriter: IBM Selectric IT, with manual, ribbon, and correction tape. 19 X 39 X 52 Cffi., in box, 32 X 46 X 66 CIDo BART Q2C3 No.1 Computers No. la Apple lie computer, CPU with drives 1 and 2, and cable connections No. lal Owner's manual No. la2 Installation manual No. la3 DOS User's manual No. la4 DOS Programmer's manual No. laS Appleworks Tutorial No. la6 80-Column Text card manual No. la7 Extended SO-Column Text and supplement No. laS Applesoft Tutorial No. la9 Appleworks startup training discs No. lalO Screenwriter II word processing manual No. lall Hayes Micro-modem lie manual No. 1b Apple Monitor ill No. lbl Owner's manual No. lc Daisy wheel printer: Brother HR 15, with tractor feed, cable, and ribbons No. lcl Instruction manual No. lc2 Instruction manual model HR 15 No. lc3 User's manual No. lc4 Tractor Feeder instruction manual I ART c No. la- lb in box, 54x49x56 em. Q2(il3 No. le in box, 19x39x48 em. No.1 Gift ofRiehard Ogar. BART Q2C34 No.1 Computer software manuals. No.1 WordPerfect. No.la Reference version 5.2 No.lb Shared applications version 1.3 No.lc Workbook for Windows version 5.2 No. ld Program discs In box, 23 x 10 x 20 em. BART Q2S2 No.1 Supplies. No.1 Carbon paper, black, standard weight and size, 8 x 11 inches/Middletown, CT.: Remington Rand, 1960? On manufacturer's box: reproduction in blue of seal bearing legend: THE UNNERSITY OF CALIFORNIA 1868 LET THERE BE LIGHT. -

Guide to Book Manufacturing Building Relationships for a Quality Experience

GUIDE TO BOOK MANUFACTURING BUILDING RELATIONSHIPS FOR A QUALITY EXPERIENCE Thomson Reuters, Guide to Book Manufacturing is a reference book intended for Thomson Reuters Core Publishing Solutions customers to give them a better understanding of the processes involved in creating, shipping, warehousing and distributing millions of books, pamphlets and newsletters produced annually. Project Lead Greg Groenjes Graphic Design Kelly Finco Vickie Jensen Janine Maxwell Contributing Writers Kelly Aune, Lori Clancy, Greg Groenjes, Brian Grunklee, Bob Holthe, Val Howard, Christine Hunter, Vickie Jensen, Sandi Krell, Linda Larson, Jerry Leyde, Kris Lundblad, Janine Maxwell, Walt Niemiec, John Reandeau, Nancy Roth, Jody Schmidt, Alex Siebenaler, Estelle Vruno Contributing Editor Christine Hunter Copy Editor Anne Kelley Conklin © 2018 Thomson Reuters. All rights reserved. July edition. TABLE OF CONTENTS Thomson Reuters Press Core Publishing Solutions Overview • Printing Background 7-1 • Thomson Reuters CPS 1-2 • Offset Presses 7-2 • Single-Color Web Press 7-2 Manufacturing Client Services • Web Press Components 7-3 (Planning & Scheduling) • Multi-Color Sheet-Fed Presses 7-6 • Service and Support 2-1 • Sheet-fed Press Description 7-6 • Roles and Responsibilities 2-2 • Sheet-fed Press Components 7-7 • Job Planning Process 2-3 • Color Printing 7-8 • Teamwork Is the Key to Success 2-5 • Colored Ink 7-8 • Considerations (Sheet-fed vs. Web) 7-9 Material Sourcing • Thomson Reuters Web Press Specifications 7-10 (Purchasing & Receiving) • Purchasing 3-1 Bindery -

Printing Presses in the Graphic Arts Collection

Printing Presses in the Graphic Arts Collection THE NATIONAL MUSEUM OF AMERICAN HISTORY 1996 This page blank Printing Presses in the Graphic Arts Collection PRINTING, EMBOSSING, STAMPING AND DUPLICATING DEVICES Elizabeth M. Harris THE NATIONAL MUSEUM OF AMERICAN HISTORY, SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION WASHINGTON D.C. 1996 Copies of this catalog may be obtained from the Graphic Arts Office, NMAH 5703, Smithsonian Institution, Washington D.C. 20560 Contents Type presses wooden hand presses 7 iron hand presses 18 platen jobbers 29 card and tabletop presses 37 galley proof and hand cylinder presses 47 printing machines 50 Lithographic presses 55 Copperplate presses 61 Braille printers 64 Copying devices, stamps 68 Index 75 This page blank Introduction This catalog covers printing apparatus from presses to rubber stamps, as well as some documentary material relating to presses, in the Graphic Arts Collection of the National Museum of American History. Not listed here are presses outside the accessioned collections, such as two Vandercook proof presses (a Model 4T and a Universal III) that are now earning an honest living in the office printing shop. At some future time, no doubt, they too will be retired into the collections. The Division of Graphic Arts was established in 1886 as a special kind of print collection with the purpose of representing “art as an industry.” For many years collecting was centered around prints, together with the plates and tools that made them. Not until the middle of the twentieth century did the Division begin to collect printing presses systematically. Even more recently, the scope of collecting has been broadened to include printing type and type-making apparatus. -

The Building of a Book

•^. f. THE BUILDING OF A BOOK THE BUILDING OF A BOOK A SEKIES OF PRACTICAL ARTI- CLES WRITTEN BY EXPERTS IN THE VARIOUS DEPARTMENTS OF BOOK MAKING AND DISTRIBUTING WITH AN INTRODUCTION BY THEODORE L. DE VINNE EDITED BY FREDERICK H. HITCHCOCK THE GRAITON PRESS PUBLISHERS NEW YORK COPTEIGHT, 1906, Bt the GRAFTON PRESS. Published December, 1906. ©etiicatctj TO RE.VDERS AND LOVERS OF BOOKS THROUGHOUT THE COUNTRY FOREWORD " The Building of a Book " had its origin in the wish to give practical, non-technical infor- mation to readers and lovers of books. I hope it will also be interesting and valuable to those persons who are actually engaged in book mak- ing and selUng. All of the contributors are experts in thoir respective departments, and hence write with authority. I am exceedingly grateful to them for their very generous efforts to make the book a success. THE EDITOR. vU ARTICLES AND CONTRIBUTORS Introduction 1 By Theodore L. De Vinne, of Theodore L. De Vinne & Company, Printers, New York. The Author 4 By George W. Cable, Author of " Grandissimes," "The Cavalier," and other books. Resident of Northampton, Massachusetts. The Literary Agent 9 By Paul R. Reynolds, Literary Agent, New York, representing several English publishing houses and American authors. The Literary Adviser 16 By Francis W. Halsey, formerly Editor of the Nexo York Times Saturday Itevieio of Books, and literary adviser for D. Appleton & Company. Now literary adviser for Funk & Wagnalls Company, New York. The Manufacturing Department ... 25 By Lawton L. Walton, in charge of the manu- facturing department of The Macmillan Company, Publishers, New York. -

Gilpin Family Rich.Ard De Gylpyn Joseph Gilpin The

THE GILPIN FAMILY FROM RICH.ARD DE GYLPYN IN 1206 IN A LINE TO JOSEPH GILPIN THE EMIGRANT TO AMERICA AND SOMETHING OF THE KENTUCKY GILPINS AND THEIR DESCENDANTS To 1916 Copyrighted in 1927 by Geor(Je Gilpin Perkins PRESS OF W, F- ROBERTS COMPANY WASHJNGTON, D, C. THE KENTUCKY GILPINS By GEORGE GILPIN PERKINS HIS genealogical study of the Gilpin families, covering the period of twenty generations prior to the Gil pin emigration to Kentucky, is gathered solely, so far as the simple line of descent goes, from an elaborate parchment pedi gree chart taken from the papers of Joshua Gilpin, Esquire, by his brother, Thomas Gilpin, Philadelphia, March, 1845, and in part, textu ally, from the work: by Dr. Joseph Elliott Gilpin, Baltimore, 1897, whose father and the Kentucky emigrants were brothers. His authority was a Genealogical Chart accompanying a manuscript published 1879 by the Cumberland and West moreland Antiquarian and Archreological Society of England entitled "Memoirs of Dr. Richard Gilpin of Scaleby Castle in Cumberland, written in the year 1791 by the Rev. William Gilpin, Vicar of Boldre, together with an account of the author by himself; and a pedigree of the Gilpin family." [ 5 ] T H E KENTUCKY GILPINS Richard de Gylpyn, the first of the name of whom there is authentic knowledge, was a scholar. He gave the family history a vigorous beginning, by becoming the Secretary and Adviser of the Baron of Kendal, who was unlearned, as were many in that day of superstition and igno rance, and accompanying him to Runnemede, where the Barons of England, after previous long parleys with the unscrupulous and tyrannical King John, forced him to grant to his oppressed people Magna Charta and, themselves, voluntarily lifted from their dependants many feudal op pressions. -

Printing History News 20

Printingprinting History history news 20 News 1 The Newsletter of the National Printing Heritage Trust, Printing Historical Society and Friends of St Bride Library Number 20 Autumn 2008 ST BRIDE EVENTS booking form, or for more information, please contact: Antiquarian Book- Glasgow 501: out of print, lecture, sellers Association, Sackville House, w1j 0dr Tuesday 21 October, Bridewell Hall, 40 Piccadilly, London . Tel: 7:00 p.m. Steve Rigley and Edwin Pick- 020 7439 3118. Fax: 020 7439 3119. stone will be talking about some of the Email: [email protected]. Wesbite: extraordinary letterpress work to have www.aba.org.uk. emerged from the University of Glas- gow’s research unit entitled ‘Out of Advance notice. The twenty-sixth Print print’ in the context of a year of cele- Networks Conference for the British brations of 500 years of printing in Book Trade Seminar will be held Scotland (see also page 2 below). between Tuesday 28 and Thursday 30 July 2009 at Trinity Hall, Cambridge. Letterpress: a celebration, one-day Further details will appear in a forth- conference, Friday 7 November, 9:30 coming issue of PHN. a.m.–5:00 p.m. There will be a packed Detail of a woodcut by Ian Mortimer, programme of talks, demonstrations I.M. Imprimit and displays of work from those keen Designer Bookbinders to share their infectious enthusiasm for Book trade conferences events letterpress in the twenty-first century. Come and join in the debates that are Books for sale: the advertising and Unless otherwise noted, the following sure to emerge. Speakers: Phil Abel promotion of print from the fifteenth events will be held at the Art Workers (Hand & Eye Letterpress), Claire century. -

Progress in Printing and the Graphic Arts During the Victorian

CORNELL UNIVERSITY LIBRARY BOUGHT WITH THE INCOME OF THE SAGE ENDOWMENT FUND GIVEN IN 1891 BY HENRY WILLIAMS SAGE Ik Cornell University Library The original of this book is in the Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31924032192373 Sir G. Hayter, R./l. Bet* Majesty Queen Tictorta in Coronation Robes. : progress in printing and the 6raphic Hrts during the Victorian Gra. "i BY John Southward, Author of "Practical Printing"; "Modern Printing"; "The Principles and Progress of Printing Machinery"; the Treatise on "Modern Typography" in the " EncyclopEedia Britannica" Cgtii Edition); "Printing" and "Types" in "Chambers's Encyclopaedia" (New Edition); "Printing" in "Cassell's Storehouse of General Information"; "Lessons on Printing" in Cassell's New Technical Educator," &c. &c. LONDON SiMPKiN, Marshall, Hamilton, Kent & Co. Ltd. 1897. X^he whole of the Roman Cypc in tbta Booh has been set up by the Linotj^pe Composing Machine, and machined direct from the Linotj'pc Bars by 6eo. CH. loncs, Saint Bride Rouse, Dean Street, fetter Lane, London, e.C. ^ ^ ^ ^ ^ ^ ^ W Contents. ^^ Progress in Jobbing Printing Chapter I. Progress in Newspaper Printing Chapter II. Progress in Book Printing - Chapter III. Printing by Hand Press Chapter IV. Printing by Power Press Chapter V. The Art of the Compositor Chapter VI. Type-Founding Chapter VII. Stereotyping and Electrotyping Chapter VIII. Process Blocks Chapter IX. Ink Manufacture Chapter X. Paper-Making Chapter XI. Description of the Illustrations Chapter XII. ^pj progress in printing peculiarity about it It is not paid for by the person who is to become its possessor. -

Support and Administration Behind the Scenes

CHAPTER 4 Support and Administration Behind the Scenes 126 eeping a vast industrial shop like GPO conformity to published standards, made ink, press humming around the clock throughout rollers, and adhesives, and performed research K its history has required a supporting to find new and better methods and materials to staff as large and diverse as the skilled force who improve GPO’s economy and efficiency. The Testing composed, printed, and bound the documents Division staff were nationally known experts in themselves. From machinists to carpenters to paper analysis, metallurgy, printing processes, inks, chemists to stock keepers, GPO’s support units and adhesives. provided the infrastructure that made possible the production of high quality printed and bound With the growth of GPO after 1900, a program of documents with speed and efficiency. apprentice training was started in the 1920s that CHAPTER 4 provided trained journeypersons for the printing and Employees in the Engineering divisions kept binding ranks, as well as the skilled support areas. Support and Administration machinery repaired, often made necessary This chapter includes photos of apprentices at work Behind the Scenes parts, maintained and improved the buildings, throughout the plant. The apprentice school grew and provided light, heat, and motive power. The to be a “university of printing and binding,” turning Stores Division tallied and moved the vast stock out generations of GPO printers, proofreaders, of raw materials like paper and binding materials bookbinders, platemakers, compositors, and other throughout GPO’s plant. GPO carpenters and skilled craftspeople. cabinetmakers produced specialized furniture and fixtures. GPO was for much of its history almost In addition to operations that directly supported entirely self-sufficient. -

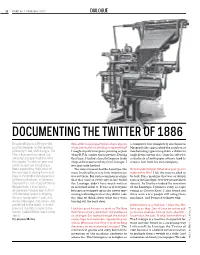

Print Magazine: February 2012 Documenting the Twitter of 1886

32 PRINT 66.1 FEBRUARY 2012 DIALOGUE DOCUMENTING THE TWITTER OF 1886 Douglas Wilson is a 29-year-old Why a film on Linotype? Did you have any pre- a computer but completely mechanical. graphic designer and letterpress vious connection to printing or typesetting? Mergenthaler approached the problem of printer by trade, and Linotype: The I taught myself letterpress printing as part mechanizing typesetting from a different Film, a documentary about the of my B.F.A. senior-thesis project. During angle from anyone else. Once he solved it, amazing Linotype machine, is his that time, I visited a local letterpress trade a syndicate of newspaper owners tried to first movie. For the last year and shop and encountered my first Linotype. I remove him from his own company. a half, he and two friends have was instantly hooked. been researching the history of The more I researched the Linotype, the That sounds familiar. What was your goal in the Linotype, traveling from rural more I realized how very little information making this film? I felt the story needed to Iowa to the modern headquarters was out there. For such a common machine be told. For a machine that was as ubiqui- of the manufacturer, in Germany. that was once in every city in the world, tous as the Linotype, very few people know The result is a rich study of Ottmar the Linotype didn't have much written about it. As I further studied the invention Mergenthaler’s contraption, or recorded about it. It was as if everyone of the Linotype, I found a story as capti- whose importance is next to that became so wrapped up in the newer type- vating as Citizen Kane. -

Machine for Outting Or Shortening Linotype Slugs. Application Filed Feb, 15, 1906

No, 823,788, PATENTED JUNE 19, 1906. R., F. JACOBS, MACHINE FOR OUTTING OR SHORTENING LINOTYPE SLUGS. APPLICATION FILED FEB, 15, 1906. 2 SHEETS-SHEET , Rew. s. GRAA co, roto-irilogRAPHERS, WASklog, c. No. 823,788, w PATENTED JUNE 19, 1906. R. F. JACOBS, MACHINE FOR OUTTING OR SHORTENING LINOTYPE SLUGS, APPLICATION FILED FEB, 15, 1906. 2 SHEETS-SHEET 2. N . <Z% E. I t a - NS s % s seass Es 9s 3 see . NSbNN (s Sse 2x ae SNN a ity al SAzeSF'ss eae Elektklubs N2S es 2 a e. N s SNSS1 a a Y FOSS al X S 24% s : X- itsa a D - - - - - - E e O se/ RSSŠ sae w Š5 NS ASSs es s N f N s Š 8wewtot le-- Aa e g s . too es SR SS 3 6%a24. (22.22% Q4 2-z, / al?y %Coorg, UNITED STATES PATENT OFFICE. ROBERT F. JACOBS, OF BALTIMORE, MARYLAND, ASSIGNOR OF ONE-HALF TO CHARLES F. WALTHER, OF HOWARDWILLE, MARYLAND. MACHINE FOR cutting OR SHORTENING LINotype-slugs. No. 828,788. Specification of Letters Patent. Patented June 19, 1906. Application filed February 15, 1906, Serial No. 301,184, To all whom it may concern: provide a slug-cutting machine with a limit 55 Be it known that I, ROBERT F. JACOBs, a ed number of attached but movable spacers citizen of the United States, residing at Bal of varying widths, the variations being ac timore, in the State of Maryland, have in cording to the point system so that one or vented certain new and useful Improvements several spacers may be quickly moved into in Machines for Cutting or Shortening Lino position, and thereby locate a stop or abut type-Slugs, of which the following is a specifi ment where it will accurately represent a cation. -

MACHINERY for BOOK and GENERAL PRINTING. Until A

FEB. 1899. 103 MACHINERY FOR BOOK AND GENERAL PRINTING. - BY ME.WILLIAM POWRIE, Member, OF LONDON. Until a comparatively recent period Typography was almost the only process employed in the production of books and other readable matter ; but it is now largely supplemented by lithography, collotypy, &c., each requiring special machinery and appliances for their effective development. In fact the operations in a modern priuting factory are specialized and carried on in departments, in a similar way to work in an engineering establishment ; and a simple list of the various machines employed would fill several pages. As an excellent detailed description of a rotary newspaper-printing machine, and the method of producing a daily paper, has been given by Mr. John Jameson in the Proceedings of this Institution for 1881 (page 511), the author purposes dealing at present with the leading classes of Machines employed for Book and Job Printing. Although the art and method of printing from movable types was invented about the beginning of the fifteenth century, it mas not until the early part of the present century that printers’ engineers and tool-makers began to produce power-driven machinery. Since then the improvement and development of printing machinery has been continuous, and more especially during the last tLirty years, until the modern printing machine bears about the same comparison with the early ones that a first-class express locomotive does with the historic ‘‘ Rocket ;” and printers’ engineering is now an important department of mechanical work. There is great diversity of details in the presses and machines used by typographic printers: some are of the “platen” kind,printing the whole surface of the sheet at once; and others are of the ‘‘ cylinder ” class, printing one line at a time, but Downloaded from pme.sagepub.com at UNIV NEBRASKA LIBRARIES on June 4, 2016 104 TYPOGKAPAIC PRINTING QfACHINERY. -

Book of Mormon Editions

Journal of Book of Mormon Studies Volume 11 Number 2 Article 7 2002 Book of Mormon Editions Larry W. Draper Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/jbms BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Draper, Larry W. (2002) "Book of Mormon Editions," Journal of Book of Mormon Studies: Vol. 11 : No. 2 , Article 7. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/jbms/vol11/iss2/7 This Feature Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Book of Mormon Studies by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Title Book of Mormon Editions Author(s) Larry W. Draper Reference M. Gerald Bradford and Alison V. P. Coutts, eds., Uncovering the Original Text of the Book of Mormon: History and Findings of the Critical Text Project, 39–44 (published in lieu of Journal of Book of Mormon Studies 11/2 [2002]). ISBN 0-934893-68-3 Abstract Larry Draper describes his role in providing Royal Skousen with copies of various early editions of the Book of Mormon for use in the critical text project. Draper also describes the printing process of the Book of Mormon, which process was made clearer because of Skousen’s project. Draper explains the stereotyping method of printing that was used for the 1840 Cincinnati/Nauvoo edition and the 1852 Liverpool edition of the Book of Mormon. Book of Mormon Editions l a r ry w. d r a p e r I was employed in the Historical Department of the (2) knowledge of the physical methods of Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints for 18 years the printing process (in other words, (until 1997).