Printing Presses in the Graphic Arts Collection

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Collection Development Policy Statement Rare Books Collection Subject Specialist Responsible

Collection Development Policy Statement Rare Books Collection Subject Specialist responsible: Doug McElrath, 301‐405‐9210, [email protected] I. Purpose The Rare Books Collection in the University of Maryland Libraries preserves physical evidence of the most successful format for recording and disseminating human knowledge: the printed codex. From the invention of printing with movable type in Asia to its widespread adoption and explosive growth in 15th century Europe, the printed book in all its forms has had an inestimable impact on the way information has been organized, spread, and consumed. The invention of printing is one of the critical technological advances that made possible the modern world. At the University of Maryland, the Rare Books Collection serves multiple purposes: As a teaching collection that preserves physical examples of the way the book has evolved over the centuries, from a hand‐crafted artifact to a mass‐produced consumable. As a research collection for targeted concentrations of printed text supporting scholarly investigation (see collection scope below). As an historical repository for outstanding examples of human accomplishment as preserved in printed formats, including seminal works in the arts, humanities, social sciences, physical and biological sciences. As a research repository for noteworthy examples of the art and craft of the book: typography, bindings, paper making, illustration, etc. As a secure storehouse for works that because of their scarcity, fragility, age, ephemerality, provenance, controversial content, or high monetary value are not appropriate for the general circulating collection. The Rare Books Collection seeks to enable researchers to interact with the physical artifact as much as possible. -

Styro-Prints Printmaking

LESSON 18 LEVEL B STYRO-PRINTS PRINTMAKING WHAT YOU WILL LEARN: learning the basic techniques of relief printmaking WHAT YOU WILL NEED: sheets of styrofoam about 13x15.5 cm.(5”x 6”) (clean flat sided styrofoam meat trays with the sides cut off) or commercial styrofoam such as Scratch-Foam Board (TM); ballpoint pen or dull pencil; black or colored water-based printing ink; one or two rubber brayers for ink, available at crafts or art supply stores; a small sheet of formica or a smooth plastic mat for an ink pad; a variety of kinds and colors of papers; damp sponge or towel; newspapers to cover work surface. Relief Print Teacher Example “TIPS”: Set up your work table as indicated in the diagram. You will Getting Started: Relief printing draw on your styrofoam “plate” some began thousands of years ago in where else and then move to the China. Much later, in Europe, wood printing place. If you have never blocks were smoothed and then cut printed before, you may want a into with sharp tools. They were then inked to make prints that grownup to help you the first time. were handed out like posters and It will be fun for both of you! handbills or flyers. In the 1500s, Important: read through all the John Gutenberg put rows of little directions before you begin to print. wooden block letters into a printing press, and the first modern books were made. In relief printing. “the ups print and the downs don’t.” That means that the surface that is inked will print and the part of the block Lesson18 A ©Silicon Valley Art Museum that is cut away or pushed down, will not. -

Abstracts Povzetki

PLACES, SPACES AND THE PRINTING PRESS: IMPRINTING REGIONAL IDENTITIES KRAJI, PROSTORI IN TISKARNE: ODTISI REGIONALNIH IDENTITET INTERNATIONAL SCIENTIFIC ONLINE CONFERENCE MEDNARODNA ZNANSTVENA KONFERENCA NA SPLETU 24. MAREC 2021 EDITORIAL BOARD dr. Ines Vodopivec dr. Caroline Archer-Parré Žiga Cerkvenik Maj Blatnik Jana Mahorčič Tomaž Bešter ORGANIZING COMMITTEE Žiga Cerkvenik Maj Blatnik ORGANIZERS Centre for Printing History and Culture at Birmingham City University at University of Birmingham, United Kingdom / Center za tiskarsko zgodovino in kulturo na Mestni univerzi Birmingham, Združeno kraljestvo National and University Library, Ljubljana, Slovenia / Narodna in univerzitetna knjižnica, Ljubljana, Slovenija. PUBLISHED BY NATIONAL AND UNIVERSITY LIBRARY, LJUBLJANA, SLOVENIA Publication is available online in PDF format at: Publikacija je dostopna v PDF formatu na spletni strani: http://www.dlib.si/details/URN:NBN:SI:doc-PDMSAPDI/ 24. 3. 2021 National and University Library, Ljubljana, copyright 2021 This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ or send a letter to Creative Commons, PO Box 1866, Mountain View, CA 94042, USA. 2 THE CONFERENCE THEME ‘Place’ is a physical entity and relates to specific locations—geographical or architectural—where particular activities are conducted. ‘Space’, on the other hand, is abstract; it is the intellectual, cultural and experiential environment in which individuals or groups congregate and collaborate. Place and space are significant to the progress of all trades, but, with the exception of the James Raven’s Bookscape: geographies of printing and publishing in London, these concepts have generally been overlooked when it comes to printing and the products of the press. -

Truly Miscellaneous Sssss

Provided by the author(s) and NUI Galway in accordance with publisher policies. Please cite the published version when available. Title Roger Fry and the art of the book: Celebrating the centenary of the Hogarth Press 1917-2017 Author(s) Byrne, Anne Publication Date 2018 Publication Byrne, Anne. (2018). Roger Fry and the Art of the Book: Information Celebrating the Centenary of the Hogarth Press 1917-2017. Virginia Woolf Miscellany, 92 (Winter/Fall), 25-29. Publisher International Virginia Woolf Society Link to https://virginiawoolfmiscellany.wordpress.com/virginia-woolf- publisher's miscellany-archive-issue-84-fall-2013-through-issue-92-fall- version 2017-winter-2018/ Item record http://hdl.handle.net/10379/15951 Downloaded 2021-09-25T22:35:05Z Some rights reserved. For more information, please see the item record link above. Space Consumes Me The hoop dancer dance...demonstrating how the people live in motion within the circling...spirals of time and space. They are no more limited than water and sky. Byrne, Anne. 2018. Roger Fry and the Paula Gunn Allen, The Sacred Hoop Truly Miscellaneous Art of the Book, Virginia Woolf Life is not a series of gig lamps symmetrically arranged, life is a luminous halo sssss Miscellany, No 92, Winter/Spring a semi-transparent envelope surrounding us from the 2018, 25-29. beginning of consciousness to the end.” Virginia Woolf, “Modern Fiction” Roger Fry and the Art of the Book: Celebrating the Centenary of the Hogarth Press 1917-20171 The earliest SPACE WAS MOTHER Making an Impression I join the friendly, excited queue around the hand-operated press, Her womb a circle of all waiting in line for an opportunity to experience the act of inking the And entry as well, a circle haloed by freshly inked plate. -

Kemble Z3 Ephemera Collection

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c818377r No online items Kemble Ephemera Collection Z3 Finding aid prepared by Jaime Henderson California Historical Society 678 Mission Street San Francisco, CA, 94105-4014 (415) 357-1848 [email protected] 2013 Kemble Ephemera Collection Z3 Kemble Z3 1 Title: Kemble Z3 Ephemera Collection Date (inclusive): 1802-2013 Date (bulk): 1900-1970 Collection Identifier: Kemble Z3 Extent: 185 boxes, 19 oversize boxes, 4 oversize folder (137 linear feet) Repository: California Historical Society 678 Mission Street San Francisco, CA 94105 415-357-1848 [email protected] URL: http://www.californiahistoricalsociety.org Location of Materials: Collection is stored onsite. Language of Materials: Collection materials are primarily in English. Abstract: The collection comprises a wide variety of ephemera pertaining to printing practice, culture, and history in the Western Hemisphere. Dating from 1802 to 2013, the collection includes ephemera created by or relating to booksellers, printers, lithographers, stationers, engravers, publishers, type designers, book designers, bookbinders, artists, illustrators, typographers, librarians, newspaper editors, and book collectors; bookselling and bookstores, including new, used, rare and antiquarian books; printing, printing presses, printing history, and printing equipment and supplies; lithography; type and type-founding; bookbinding; newspaper publishing; and graphic design. Types of ephemera include advertisements, announcements, annual reports, brochures, clippings, invitations, trade catalogs, newspapers, programs, promotional materials, prospectuses, broadsides, greeting cards, bookmarks, fliers, business cards, pamphlets, newsletters, price lists, bookplates, periodicals, posters, receipts, obituaries, direct mail advertising, book catalogs, and type specimens. Materials printed by members of Moxon Chappel, a San Francisco-area group of private press printers, are extensive. Access Collection is open for research. -

A Dictionary of Typography and Its Accessory Arts. Presented to the Subscribers of the "Printers' Register," 1870

: Supplement to tin- "^rtnters 1 Register," September vt, mdccclxxi. "*>. > % V V .. X > X V X V * X X V s X X X V S X S X V X X S X X V X .X X X\x X X .X X X N .N .X X S A t. y littimrarg uprjrajjlur i f / / 4 / / / AND / I '/ ITS ACCESSORY ARTS /• - I / / i 7 ': BY / / I /; r JOHN SOUTHWARD. / /. / / / i ^rescntcb to the Subscribers of the "^printers' T^cgistcr. 1870-1871. / n V / gonfcon JOSEPH M. POWELL, "PRINTERS' REGISTER" OFFICE, 3, BOUVERIE STREET, E.( . / PRINTED 9Y DANIEL & CO., ST. LEONARDS-ON-SEA j — 2? 113 %\%\ of JutjiOUtlCS. Among the various works on the Art of Printing, consulted in the compilation ol this Dictionary, may be named the following : Abridgments of Specifications relating to Printing. Johnson's Typographia. Andrews's History of British Journalism. Knight's Caxton. Annales de la Typographic Francaise et etrangere. Knight's Knowledge is Powei Annales de ITmprimerie. knight's Old Printer and the Modern Pres> xviii. Annals of Our Time. London Encyclopedia. Printing— vol. p , Annuaire de la Librairie et de ITmprimerie. Mi' {Cellar's American Printer. Cabbage's Economy of Machinery and Manufactures. Marahren's Handbuch der Typographic Bullhorn's Grammatography. Maverick's Henry J. Raymund and the New York IV---. Beadnell's Guide to Typography. McCreery's Press, a Poem. Biographical Memoirs of William (Jed. Morgan's Dictionary of Terms u.sed in Printing. Buckingham's Personal Memoirs and Recollections of Editorial Life. Moxon's Mechanick Exercis Buckingham's Specimens of Newspaper Literature. -

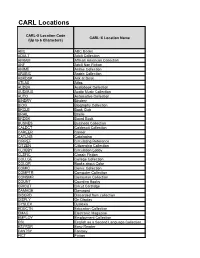

CARL Locations

CARL Locations CARL•X Location Code CARL•X Location Name (Up to 6 Characters) ABC ABC Books ADULT Adult Collection AFRAM African American Collection ANF Adult Non Fiction ANIME Anime Collection ARABIC Arabic Collection ASKDSK Ask at Desk ATLAS Atlas AUDBK Audiobook Collection AUDMUS Audio Music Collection AUTO Automotive Collection BINDRY Bindery BIOG Biography Collection BKCLB Book Club BRAIL Braille BRDBK Board Book BUSNES Business Collection CALDCT Caldecott Collection CAREER Career CATLNG Cataloging CIRREF Circulating Reference CITZEN Citizenship Collection CLOBBY Circulation Lobby CLSFIC Classic Fiction COLLGE College Collection COLOR Books about Color COMIC Comic Collection COMPTR Computer Collection CONSMR Consumer Collection COUNT Counting Books CRICUT Cricut Cartridge DAMAGE Damaged DISCRD Discarded from collection DISPLY On Display DYSLEX Dyslexia EDUCTN Education Collection EMAG Electronic Magazine EMPLOY Employment Collection ESL English as a Second Language Collection ESYRDR Easy Reader FANTSY Fantasy FICT Fiction CARL•X Location Code CARL•X Location Name (Up to 6 Characters) GAMING Gaming Collection GENEAL Genealogy Collection GOVDOC Government Documents Collection GRAPHN Graphic Novel Collection HISCHL High School Collection HOLDAY Holiday HORROR Horror HOURLY Hourly Loans for Pontiac INLIB In Library INSFIC Inspirational Fiction INSROM Inspirational Romance INTFLM International Film INTLNG International Language Collection JADVEN Juvenile Adventure JAUDBK Juvenile Audiobook Collection JAUDMU Juvenile Audio Music Collection -

Read-Aloud Chapter Books for Younger Children for Children Through 3 Rd Grade Remember to Choose a Story That You Will Also Enjoy

Read-Aloud Chapter Books for Younger Children rd for children through 3 grade Remember to choose a story that you will also enjoy The Wolves of Willoughby Chase by Joan Aiken: Surrounded by villains of the first order, brave Bonnie and gentle cousin Sylvia conquer all obstacles in this Victorian melodrama. Poppy by Avi: Poppy the deer mouse urges her family to move next to a field of corn big enough to feed them all forever, but Mr. Ocax, a terrifying owl, has other ideas. The Indian in the Cupboard by Lynne Reid Banks: A nine-year-old boy receives a plastic Indian, a cupboard, and a little key for his birthday and finds himself involved in adventure when the Indian comes to life in the cupboard and befriends him. Double Fudge by Judy Blume: His younger brother's obsession with money and the discovery of long-lost cousins Flora and Fauna provide many embarrassing moments for twelve-year-old Peter. The Mouse and the Motorcycle by Beverly Cleary: A reckless young mouse named Ralph makes friends with a boy in room 215 of the Mountain View Inn and discovers the joys of motorcycling. How to Train Your Dragon by Cressida Cowell : Chronicles the adventures and misadventures of Hiccup Horrendous Haddock the Third as he tries to pass the important initiation test of his Viking clan, the Tribe of the Hairy Hooligans, by catching and training a dragon. Understood Betsy by Dorothy Canfield Fisher: Timid and small for her age, nine- year-old Elizabeth Ann discovers her own abilities and gains a new perception of the world around her when she goes to live with relatives on a farm in Vermont. -

IBM Selectric IT, with Manual, Ribbon, and Correction Tape

BART Q2B2 No. 1-2 Typewriters. No.1 Manual typewriter: Remington, 1965 with library keyboard. 23 x 36 x 49 em. No. 2 Electric typewriter: IBM Selectric IT, with manual, ribbon, and correction tape. 19 X 39 X 52 Cffi., in box, 32 X 46 X 66 CIDo BART Q2C3 No.1 Computers No. la Apple lie computer, CPU with drives 1 and 2, and cable connections No. lal Owner's manual No. la2 Installation manual No. la3 DOS User's manual No. la4 DOS Programmer's manual No. laS Appleworks Tutorial No. la6 80-Column Text card manual No. la7 Extended SO-Column Text and supplement No. laS Applesoft Tutorial No. la9 Appleworks startup training discs No. lalO Screenwriter II word processing manual No. lall Hayes Micro-modem lie manual No. 1b Apple Monitor ill No. lbl Owner's manual No. lc Daisy wheel printer: Brother HR 15, with tractor feed, cable, and ribbons No. lcl Instruction manual No. lc2 Instruction manual model HR 15 No. lc3 User's manual No. lc4 Tractor Feeder instruction manual I ART c No. la- lb in box, 54x49x56 em. Q2(il3 No. le in box, 19x39x48 em. No.1 Gift ofRiehard Ogar. BART Q2C34 No.1 Computer software manuals. No.1 WordPerfect. No.la Reference version 5.2 No.lb Shared applications version 1.3 No.lc Workbook for Windows version 5.2 No. ld Program discs In box, 23 x 10 x 20 em. BART Q2S2 No.1 Supplies. No.1 Carbon paper, black, standard weight and size, 8 x 11 inches/Middletown, CT.: Remington Rand, 1960? On manufacturer's box: reproduction in blue of seal bearing legend: THE UNNERSITY OF CALIFORNIA 1868 LET THERE BE LIGHT. -

Introduction to Printing Technologies

Edited with the trial version of Foxit Advanced PDF Editor To remove this notice, visit: www.foxitsoftware.com/shopping Introduction to Printing Technologies Study Material for Students : Introduction to Printing Technologies CAREER OPPORTUNITIES IN MEDIA WORLD Mass communication and Journalism is institutionalized and source specific. Itfunctions through well-organized professionals and has an ever increasing interlace. Mass media has a global availability and it has converted the whole world in to a global village. A qualified journalism professional can take up a job of educating, entertaining, informing, persuading, interpreting, and guiding. Working in print media offers the opportunities to be a news reporter, news presenter, an editor, a feature writer, a photojournalist, etc. Electronic media offers great opportunities of being a news reporter, news editor, newsreader, programme host, interviewer, cameraman,Edited with theproducer, trial version of Foxit Advanced PDF Editor director, etc. To remove this notice, visit: www.foxitsoftware.com/shopping Other titles of Mass Communication and Journalism professionals are script writer, production assistant, technical director, floor manager, lighting director, scenic director, coordinator, creative director, advertiser, media planner, media consultant, public relation officer, counselor, front office executive, event manager and others. 2 : Introduction to Printing Technologies INTRODUCTION The book introduces the students to fundamentals of printing. Today printing technology is a part of our everyday life. It is all around us. T h e history and origin of printing technology are also discussed in the book. Students of mass communication will also learn about t h e different types of printing and typography in this book. The book will also make a comparison between Traditional Printing Vs Modern Typography. -

Corrugated 101! ! !Corrugated Vs

Corrugated 101! ! !Corrugated vs. Cardboard! • The term "cardboard box" is commonly misused when referring to a corrugated box. The correct technical term is "corrugated fiberboard carton.”! • Cardboard boxes are really chipboard boxes, and used primarily for packaging lightweight products, such as cereal or board games.! • Corrugated fiberboard boxes are widely utilized in retail packaging, shipping cartons, product displays and many other applications ! requiring lightweight, but sturdy materials.! !Corrugated Composition! Corrugated fiberboard is comprised of linerboard and heavy paper medium. Linerboard is the flat, outer surface that adheres to the medium. The medium is the wavy, fluted paper between the liners. Both are made of a special kind of heavy paper called !containerboard. Board strength will vary depending on the various linerboard and medium combinations.! • Single Face: Medium glued to 1 linerboard; flutes exposed! • Single Wall: Medium between 2 liners! • Double Wall: Varying mediums layered between 3 liners! !• Triple Wall: Varying mediums layered between 4 liners! !Flute Facts! !Corrugated board can be created with several different flute profiles. The five most common flute profiles are:! • A-Flute: Original corrugated flute design. Contains about 33 flutes per foot.! • B-Flute: Developed primarily for packaging canned goods. Contains about 47 flutes per foot and measures 1/8" thick! • C-Flute: Commonly used for shipping cartons. Contains about 39 flutes per foot and measures 5/32" thick! • E-Flute: Contains about 90 flutes per foot and measures 1/16" thick! • F-Flute: Developed for small retail packaging. Contains about 125 flutes per foot and measures 1/32" thick! • Generally, larger flute profiles deliver greater vertical compression strength and cushioning. -

Manufacturing of Paperboard and Corrugated Board Packages

Lecture 9: Manufacturing of paperboard and corrugated board packages Converting operations: printing, die-cutting, folding, gluing, deep-drawing After lecture 9 you should be able to • describe the most important converting operations in paper and paperboard package manufacturing • discuss important runnability considerations in paperboard package handling • relate factors affecting runnability to pppaperboard app earance and pyphysical performance quality parameters 1 Literature • Pulp and Paper Chemistry and Technology - Volume 4, Paper Products Physics and Technology, Chapter 10 • Paperboard Reference Manual, p. 157-225 • Fundamentals of packaging technology Chapters 4, 6, 15 and 18 Paperboard Packaging Design is the result of • Personal creativity plus – Knowledge and understanding of packaging materials, including: • Structural properties • Graphic capabilities • Converting processes and converting properties • Customer packaging systems • Marketing objectives • Distribution requirements • Retail outlet expectations • Needs and desires of end user • How end user will use the product • Many people may contribute to the design 2 Overall, the design must provide: • Containment of product • Protection of product • Ease in handling through distribution • Prevention of product spoilage • Tamper evidence • Consumer convenience • Brand identification • Communications for the consumer: – Instructions for product use – Coding for quality assurance, expiration dates – Dietary and nutritional information The design should consider: 1. Converting