How Venture Capital Changes the Laws of Economics Working Paper

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Leaving Reality Behind Etoy Vs Etoys Com Other Battles to Control Cyberspace By: Adam Wishart Regula Bochsler ISBN: 0066210763 See Detail of This Book on Amazon.Com

Leaving Reality Behind etoy vs eToys com other battles to control cyberspace By: Adam Wishart Regula Bochsler ISBN: 0066210763 See detail of this book on Amazon.com Book served by AMAZON NOIR (www.amazon-noir.com) project by: PAOLO CIRIO paolocirio.net UBERMORGEN.COM ubermorgen.com ALESSANDRO LUDOVICO neural.it Page 1 discovering a new toy "The new artist protests, he no longer paints." -Dadaist artist Tristan Tzara, Zh, 1916 On the balmy evening of June 1, 1990, fleets of expensive cars pulled up outside the Zurich Opera House. Stepping out and passing through the pillared porticoes was a Who's Who of Swiss society-the head of state, national sports icons, former ministers and army generals-all of whom had come to celebrate the sixty-fifth birthday of Werner Spross, the owner of a huge horticultural business empire. As one of Zurich's wealthiest and best-connected men, it was perhaps fitting that 650 of his "close friends" had been invited to attend the event, a lavish banquet followed by a performance of Romeo and Juliet. Defiantly greeting the guests were 200 demonstrators standing in the square in front of the opera house. Mostly young, wearing scruffy clothes and sporting punky haircuts, they whistled and booed, angry that the opera house had been sold out, allowing itself for the first time to be taken over by a rich patron. They were also chanting slogans about the inequity of Swiss society and the wealth of Spross's guests. The glittering horde did its very best to ignore the disturbance. The protest had the added significance of being held on the tenth anniversary of the first spark of the city's most explosive youth revolt of recent years, The Movement. -

PORTABLE MBA in PROJECT MANAGEMENT the Portable MBA Series

PORTABLE MBA in PROJECT MANAGEMENT The Portable MBA Series The Portable MBA, Fourth Edition, Robert Bruner, Mark Eaker, R. Edward Freeman, Robert Spekman, Elizabeth Teisberg, and S. Venkataraman The Portable MBA Desk Reference, Second Edition, Nitin Nohria The Portable MBA in Economics, Philip K. Y. Young The Portable MBA in Entrepreneurship, Second Edition, William D. Bygrave The Portable MBA in Entrepreneurship Case Studies, William D. Bygrave The Portable MBA in Finance and Accounting, Third Edition, John Leslie Livingstone and Theodore Grossman The Portable MBA in Investment, Peter L. Bernstein The Portable MBA in Management, Second Edition, Allan R. Cohen The Portable MBA in Market-Driven Management: Using the New Marketing Concept to Create a Customer-Oriented Company, Frederick E. Webster The Portable MBA in Marketing, Second Edition, Alexander Hiam and Charles Schewe The Portable MBA in New Product Development: Managing and Forecasting for Strategic Success, Robert J. Thomas The Portable MBA in Psychology for Leaders, Dean Tjosvold The Portable MBA in Real-Time Strategy: Improvising Team-Based Planning for a Fast-Changing World, Lee Tom Perry, Randall G. Stott, and W. Norman Smallwood The Portable MBA in Strategy, Second Edition, Liam Fahey and Robert Randall The Portable MBA in Total Quality Management: Strategies and Techniques Proven at Today’s Most Successful Companies, Stephen George and Arnold Weimerskirch PORTABLE MBA in PROJECT MANAGEMENT EDITED BY ERIC VERZUH John Wiley & Sons, Inc. This book is printed on acid-free paper. ➇ Copyright © 2003 by John Wiley & Sons, Inc. All rights reserved. Published by John Wiley & Sons, Inc., Hoboken, New Jersey. Published simultaneously in Canada. -

Elenco Titoli Non Complessi

Codice prodotto/ISIN Denominazione Tipo prodotto IT0004746647 BNL FRN 29/07/2016 Obbligazione FR0010859967 BNP PARIBAS PS 3,75% 26/02/2020 Obbligazione XS0653885961 BMW FINANCE 3,625% 29/01/2018 Obbligazione XS0490567616 BIRS 3,75% 19/05/2017 Obbligazione AN8068571086 SCHLUMBERGER (NEW YORK) Azione ANN963511061 WHN WORLD HEALTH NETWORK Azione AT00000BENE6 BENE Azione AT0000609631 ALLGEMEINE BAUGESELLSCHAFT Azione AT0000617808 AUSTRIA ANTRIEBESTECHNIK G Azione AT0000624739 BSK BANK PRIV Azione IT0004647522 BP FRIULADRIA FRN 29/08/2017 STEP UP Obbligazione AT0000652201 DIE ERSTE IMMOBILIEN AG AOR Azione GB00B2QM7Y61 BARCLAYS SU BRC RMF DIVERS MAG17 (NQ) Warrant AT0000728209 MANNER JOSEF & CO Azione AT0000734835 MIBA AG Azione AT0000741301 KAPITAL & WERT VERM. SVERWALTUNG Azione AT0000746409 OESTERREICHISCHE ELEKTRIZITAETSW Azione AT0000747555 UPDATE COM SOFTWARE Azione AT0000758305 PALFINGER AG Azione AT0000776307 SANOCHEMIA PHARMAZEUTIKA AG AOR Azione AT0000779038 SCHLUMBERGER AG AOR PREFERRED Azione AT0000793658 ADCON TELEMETRY AG AOR Azione AT0000808209 SW UMWELTTECHNIK STOISER & WOLSCH Azione AT0000816301 UNTERNEHMENS INVEST. AG AOR Azione AT0000820659 BRAIN FORCE SOFTWARE AG Azione AT0000834007 WOLFORD AG Azione AT0000837307 ZUMTOBEL Azione AT0000908520 WIENER STAEDTISCHE VERSICHERUNG AG Azione AT0000A02177 BDI BIODIESEL INT Azione AT0000A08968 AUSTRIA 4,35% 15/03/2019 Obbligazione AT0000A0MS25 CA-IMMOBILIEN ANLAGEN Azione IE00B95FFX04 ETF UBS MAP BALANCED 7 UCITS EUR CL. A (XETRA) Fondo AU000000AMP6 AMP LIMITED Azione AU000000ANZ3 -

The Great Telecom Meltdown for a Listing of Recent Titles in the Artech House Telecommunications Library, Turn to the Back of This Book

The Great Telecom Meltdown For a listing of recent titles in the Artech House Telecommunications Library, turn to the back of this book. The Great Telecom Meltdown Fred R. Goldstein a r techhouse. com Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data A catalog record for this book is available from the U.S. Library of Congress. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Goldstein, Fred R. The great telecom meltdown.—(Artech House telecommunications Library) 1. Telecommunication—History 2. Telecommunciation—Technological innovations— History 3. Telecommunication—Finance—History I. Title 384’.09 ISBN 1-58053-939-4 Cover design by Leslie Genser © 2005 ARTECH HOUSE, INC. 685 Canton Street Norwood, MA 02062 All rights reserved. Printed and bound in the United States of America. No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. All terms mentioned in this book that are known to be trademarks or service marks have been appropriately capitalized. Artech House cannot attest to the accuracy of this information. Use of a term in this book should not be regarded as affecting the validity of any trademark or service mark. International Standard Book Number: 1-58053-939-4 10987654321 Contents ix Hybrid Fiber-Coax (HFC) Gave Cable Providers an Advantage on “Triple Play” 122 RBOCs Took the Threat Seriously 123 Hybrid Fiber-Coax Is Developed 123 Cable Modems -

Valuation and Start-Up Strategies Class News

290T: The Business of Software: Valuation and Start-up Strategies Professor Kurt Keutzer Fall 2003 EECS [email protected] 1 Class News • Sorry, can’t make my office hour this week 3-4PM Tuesday, I’ll move it to Wed 2-3PM 2 landay 1 Valuation • The key common element between these: Start-up/ Entry Valuation Exit 3 Valuable Business Skills 1. The ability to predict the future 2. The ability to judge people 3. The ability to identify the value (and its direction arrow) of a technology, product, company, market or industry 4. The ability to develop a valuable technology, product, company, market or industry 4 landay 2 So, let’s get started! How do we value these? • A pen? • The cost to replace it • A diamond? • Table look up on size, cut, index of refraction, color (the 4C’s) • An oil well? • The value of seven years production • A year of your work life • Comparable salaries • Opportunity cost!!! 5 So, let’s get started! How do we value these? • A house? • Market comparison (comparables) • Cost of land and construction • Income: • Estimated_rental_income – mortgage - taxes – maintenance * 12 * 30 • Includes: risk, maintenance • What other factors could affect the sale? • Unique features of the property (house provides access to other valuable property) • Disposition of buyers • Disposition of sellers 6 landay 3 Buyers and Sellers • How many sellers have a comparable product? • Disposition of seller • Doesn’t want to sell • Willing to sell, but in no hurry • In the mood to sell • Anxious to sell • How many buyers are there? • Disposition of the buyer • Disinterested • Interested, but passively so • Actively interested • MUST HAVE! 7 Why do we need to value start-ups? • To raise capital • Invested capital buys some portion of company • Need to value start-up to determine how much money will buy • For example: myNewStartup, Inc. -

Shuchita Times August 2019

ISSN : 0972-7124 August 2019 Volume 20 No. 8 ISSN : 0972-7124 August 2019 Volume 20 No. 8 Freedom is never more than one generation away from extinction. We didn't pass it to our children in the bloodstream. It must be fought for, protected, and handed on for them to do the same. - Ronald Reagan Contents Page No. Dear Friends, Dot-Com Bubble (1997 - 2001) 3 Freedom doesn’t mean you decide the way you Commerce Quiz 5 want. Freedom means responsibility, and the Hasta La Vista Monsoon Flu 5 independence is maintained by responsible freedom. Personality of the Month-Mr. Pranav Yadav 13 Freedom is nothing but a chance to be better and The Mother & the Wolf 13 earn peace. You can't separate peace from freedom Our Booksellers 24 because no one can be at peace unless he has his Cynosure of the Month 26 freedom. Being free is not merely to cast off one’s own shackles, but to live in a way that respects and enriches the freedom of others as well. Executive Editor Prof. Arun Kumar Freedom is always precarious, but it is the safest Editor thing we have. Respect your people who work hard for Dr. Priyadarshani Singh your freedom and ensure your part in this elevation. Happy Independence Day! Dr. K. K. Patra Prof. B. M. Agrawal Prof. M. P. Gupta CA Shashwat Singhal Dr. Pavan Jaiswal, CWA Sri Gaurab Ghosh Dr. Arpita Ghosh CA Ganpat Kumar CA Amar Omar CA Dilip Badlani CS (Dr.) Himanshu Srivastava CA Mohit Bahal Graphics Sai Graphics Editorial Office 25/19, L.I.C. -

HOW DID SILICON VALLEY BECOME SILICON VALLEY? Three Surprising Lessons for Other Cities and Regions

HOW DID SILICON VALLEY BECOME SILICON VALLEY? Three Surprising Lessons for Other Cities and Regions a report from: supported by: 2 / How Silicon Valley Became "Silicon Valley" This report was created by Rhett Morris and Mariana Penido. They wish to thank Jona Afezolli, Fernando Fabre, Mike Goodwin, Matt Lerner, and Han Sun who provided critical assistance and input. For additional information on this research, please contact Rhett Morris at [email protected]. How Silicon Valley Became "Silicon Valley" / 3 INTRODUCTION THE JOURNALIST Don Hoefler coined the York in the chip industry.4 No one expected the term “Silicon Valley” in a 1971 article about region to become a hub for these technology computer chip companies in the San Francisco companies. Bay Area.1 At that time, the region was home to Silicon Valley’s rapid development offers many prominent chip businesses, such as Intel good news to other cities and regions. This and AMD. All of these companies used silicon report will share the story of its creation and to manufacture their chips and were located in analyze the steps that enabled it to grow. While a farming valley south of the city. Hoefler com- it is impossible to replicate the exact events that bined these two facts to create a new name for established this region 50 years ago, the devel- the area that highlighted the success of these opment of Silicon Valley can provide insights chip businesses. to leaders in communities across the world. Its Silicon Valley is now the most famous story illustrates three important lessons for cul- technology hub in the world, but it was a very tivating high-growth companies and industries: different place before these businesses devel- oped. -

1 UNITED STATES SECURITIES and EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C

1 UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20549 FORM 13F FORM 13F COVER PAGE Report for the Calendar Year or Quarter Ended: September 30, 2000 Check here if Amendment [ ]; Amendment Number: This Amendment (Check only one.): [ ] is a restatement. [ ] adds new holdings entries Institutional Investment Manager Filing this Report: Name: AMERICAN INTERNATIONAL GROUP, INC. Address: 70 Pine Street New York, New York 10270 Form 13F File Number: 28-219 The Institutional Investment Manager filing this report and the person by whom it is signed represent that the person signing the report is authorized to submit it, that all information contained herein is true, correct and complete, and that it is understood that all required items, statements, schedules, lists, and tables, are considered integral parts of this form. Person Signing this Report on Behalf of Reporting Manager: Name: Edward E. Matthews Title: Vice Chairman -- Investments and Financial Services Phone: (212) 770-7000 Signature, Place, and Date of Signing: /s/ Edward E. Matthews New York, New York November 14, 2000 - ------------------------------- ------------------------ ----------------- (Signature) (City, State) (Date) Report Type (Check only one.): [X] 13F HOLDINGS REPORT. (Check if all holdings of this reporting manager are reported in this report.) [ ] 13F NOTICE. (Check if no holdings reported are in this report, and all holdings are reported in this report and a portion are reported by other reporting manager(s).) [ ] 13F COMBINATION REPORT. (Check -

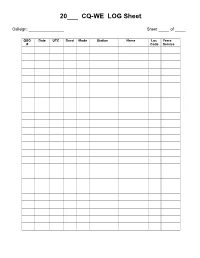

CQWE Contest Packet

20___ CQ-WE LOG Sheet Callsign: ________________ Sheet _____ of _____ QSO Date UTC Band Mode Station Name Loc Years # Code Service 2020 CQ-WE LOCATION CHECK SHEET (Duplicate this sheet as needed.) Your Call___________________________ Circle one: CW PHONE DIGITAL These are the only Locations valid for this year's contest. Any additions will not be accepted. A Location Check Sheet must be filled out for each Category of operation. Enter the call letters of the first station worked for each location. Call Location Call Location Call Location __________ AC AT&T Headquarters __________ LJ AT&T Communications __________ QJ C&P Telephone Co VA __________ AE Alcatel-Lucent, Europe __________ LZ Avaya – Lincroft __________ QK Ameritech Services __________ AK Atlanta Works-Norcross __________ MD Morris Township Fac __________ QM Bell South __________ AL Allentown Works __________ MG Montgomery Works __________ QN Ohio Bell Telephone __________ AT Atlanta Works __________ MH Bell Labs-Murray Hill __________ QP Cincinnati Bell __________ BA Baltimore Works __________ MI Miami Service Ctr __________ QR Indiana Bell __________ BB PLPM Trans Eqpt __________ MN Michigan Service Ctr __________ QS Michigan Bell __________ BC Bellcore/SAIC-NJ __________ MP Minneapolis Svc Ctr __________ QT Illinois Bell __________ BH Birmingham, AL __________ MR Mountain NE Region __________ QV Southwestern Bell __________ BK Berkeley Heights, NJ __________ MS Northwest Bell Inst __________ QW Mountain States Tel __________ CA California Service Ctr __________ MT AT&T – -

Role of Venture Capital in Economic Growth of United States

Role of Venture Capital in Economic Growth of United States - Maria Ben ________________________________________________________________________________ Venture capital is a form of financing used by startups and young companies at different stages of their growth. At early stages of development, raising debt capital is extremely difficult for young companies owing to the huge uncertainties involved. Young companies, especially those with business models that aren’t fully proven, or firms that haven’t reached their break even, find it extremely difficult to access funding. This is where VCs play a huge role by making risky investments in startups and young companies in return for equity ownership. The role that VCs play is not limited to capital contribution, they also provide mentorship, industry connect and an entire network of support systems which enables in large scale expansion of young business models. Not only is it beneficial to entrepreneurs, but it also has several other positive impacts. This article explores one such aspect of venture capital; how it is a fuel for innovation and economic growth in countries like the United States. In 2018, out of the ten most valuable companies in the world, seven of them were startups that had humble beginnings and were funded by venture capital. These include – Apple, Amazon, Alphabet(Google), Microsoft, Facebook, Alibaba and Tencent. Interestingly, five out of these seven companies belong to the United States which is also home to Silicon Valley, the hub of 1 entrepreneurship and venture capitalism . According to a study conducted by Stanford University, public companies in the United States with venture capital backing, employ about four million people and account for one-fifth of the total market capitalization.(Stanford) (World’s most valuable companies in terms of market capitalisation in 2018) Source: statistica.com 1 "Investing and Economics Blog." The 20 Most Valuable Companies in the World – Jan 2019 at Curious Cat Investing and Economics Blog. -

Lehman Brothers Holdings

SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION FORM 13F-HR/A Initial quarterly Form 13F holdings report filed by institutional managers [amend] Filing Date: 2004-12-01 | Period of Report: 2004-09-30 SEC Accession No. 0000806085-04-000212 (HTML Version on secdatabase.com) FILER LEHMAN BROTHERS HOLDINGS INC Mailing Address Business Address LEHMAN BROTHERS LEHMAN BROTHERS CIK:806085| IRS No.: 133216325 | State of Incorp.:DE | Fiscal Year End: 1130 745 SEVENTH AVENUE 745 SEVENTH AVENUE Type: 13F-HR/A | Act: 34 | File No.: 028-03182 | Film No.: 041177215 NEW YORK NY 10019 NEW YORK NY 10019 SIC: 6211 Security brokers, dealers & flotation companies 2125267000 Copyright © 2012 www.secdatabase.com. All Rights Reserved. Please Consider the Environment Before Printing This Document NON-CONFIDENTIAL <TABLE> <CAPTION> TITLE OF VALUE SHRS OR SH/ PUT/ INVESTMENT OTHER VOTING AUTHORITY NAME OF ISSUER CLASS CUSIP (X$1000) PRN AMT PRN CALL DISCRETION MANAGERS SOLE SHARED NONE <S> <C> <C> <C> <C> <C> <C> -------------------------------- -------- --------- -------- ------- --- ---- ---------- -------- -------- -------- -------- ***DAIMLERCHRYSLER A.G. COMMON D1668R123 9514 227843 SH DEFINED 01 227843 0 0 ***SANOFI AVENTIS COMMON F5548N101 34013 491666 SH DEFINED 01 491666 0 0 PNM RESOURCES COMMON GKD49H100 0 50000 SH DEFINED 01 0 0 50000 PNM RESOURCES COMMON GKD49H100 0 200000 SH DEFINED 01 200000 0 0 ***ACE LTD-ORD COMMON G0070K103 9964 248616 SH DEFINED 01 0 0 248616 ***ASPEN INSURANCE HOLDINGS COMMON G05384105 3950 171680 SH DEFINED 01 171680 0 0 ***ASSURED GUARANTY -

The Great Telecom Meltdown

4 The Internet Boom and the Limits to Growth Nothing says “meltdown” quite like “Internet.” For although the boom and crash cycle had many things feeding it, the Internet was at its heart. The Internet created demand for telecommunications; along the way, it helped create an expectation of demand that did not materialize. The Internet’s commercializa- tion and rapid growth led to a supply of “dotcom” vendors; that led to an expec- tation of customers that did not materialize. But the Internet itself was not at fault. The Internet, after all, was not one thing at all; as its name implies, it was a concatenation [1] of networks, under separate ownership, connected by an understanding that each was more valuable because it was able to connect to the others. That value was not reduced by the mere fact that many people overesti- mated it. The ARPAnet Was a Seminal Research Network The origins of the Internet are usually traced to the ARPAnet, an experimental network created by the Advanced Research Projects Agency, a unit of the U.S. Department of Defense, in conjunction with academic and commercial contrac- tors. The ARPAnet began as a small research project in the 1960s. It was pio- neering packet-switching technology, the sending of blocks of data between computers. The telephone network was well established and improving rapidly, though by today’s standards it was rather primitive—digital transmission and switching were yet to come. But the telephone network was not well suited to the bursty nature of data. 57 58 The Great Telecom Meltdown A number of individuals and companies played a crucial role in the ARPAnet’s early days [2].