MSC Newsletter 4-2017

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MSC Newsletter 04-2016

The MidMid----SouthSouth Flyer Spring 2016 A Quarterly Publication of the Mid-South Chapter of the Railway & Locomotive Historical Society, Inc April Meeting Highlight Presenting Frank Ardrey — in color! Anyone familiar with the name of Frank Ardrey knows of Frank’s reputation as one of the South’s leading black & white photographers from the post-WWII era. Pick up most any book of Southeastern railroad pho- tography from the period, and you’ll find examples of Frank’s classic shots of steam and first-generation die- sel power in an around the Birmingham District. With the passing of steam, Frank laid down his camera and retired to his photo lab, where he spent many happy hours developing untold prints from his large format negative collection to sell and trade with other photographers. Then in the mid-1960s, Frank picked up a 35mm cam- era and set out to document the remaining small-town On one of his depot junkets, Frank grabbed this well-framed shot of railroad depots before they, too, had all disappeared. Southern’s “Birmingham Special” at Attalla, AL in January 1967 What isn’t generally known is that during his depot rambles, Frank also photographed the trains that happened by, much as he did back in the day when he would shoot the occasional diesel-powered train as he waited to take a steam shot. But with one significant differ- ence: While the bulk of his early photography was black & white, Frank’s later shots were taken in color! According to son Carl, from the mid-60s to mid-70s, Frank catalogued around 2,500 Kodachrome slides of freight and passenger trains across the Southeast. -

Report on Streamline, Light-Weight, High-Speed Passenger Trains

T F 570 .c. 7 I ~38 t!of • 3 REPORT ON STREAMLINE, LIGHT-WEIGHT, HIGH-SPEED PASSENGER TRAINS June 30, 1938 • DEC COVE RDALE & COL PITTS CONSULTING ENGINEERS 120 WALL STREE:T, N ltW YORK REPORT ON STREAMLINE, LIGHT-WEIGHT HIGH-SPEED PASSENGER TRAINS June 30. 1938 COVERDALE & COLPITTS " CONSUL..TING ENGINEERS 1a0 WALL STREET, NEW YORK INDEX PAOES J NTRODUC'r!ON • s-s PR£FATORY R£MARKS 9 uNION PAC! FIC . to-IJ Gen<ral statement City of Salina >ioRTH WESTERN-UNION PAcln c City of Portland City of Los Angd<S Cit)' of Denve'r NoRTH W£sTERN-l.:~<IOS P \ l"IIIC-Sm 1HrR" PACirJc . '9"'~1 Cit)' of San Francisco Forty Niner SouTHERN PAclnC. Sunbeam Darlight CHICAco, BuR~lNGTON & QuiN<'' General statement Origin:tl Zephyr Sam Houston Ourk State Mark Twain Twin Citi<S Zephyn Den\'tr Zephyrs CHICACO, ~ULWACK.EE, ST. l'AUL AND PACit' lt• Hiawatha CHICAOO AND NoRTH \Yss·rr;J<s . ,; -tOO" .•hCHISON, T orEKJ\ AND SAN'rA FE General statement Super Chief 1:.1 Capitan Son Diegon Chicagoan and Kansas Cityon Golden Gate 3 lJID£X- COIIIinutd PACES CmCAco, RocK IsLAND AND PACIFIC 46-50 General statement Chicago-Peoria Rocket Chicago-Des Moines Rocket Kansas City-Minneapolis Rocket Kansas City-Oklahoma City Rocket Fort Worth-Dallas-Houston Rocket lLuNOJS CENTRAL • Green Diamond GULF, MOBlL£ AI<D NORTHERN 53-55 Rebels New YoRK Cesr&AI•. Mercury Twentieth Century Limited, Commodore Vanderbilt PENNSYLVANiA . 57 Broadway Lirruted, Liberty Limited, General, Spirit of St. Louis BALTIMORE AND 0HJO • ss Royal Blue BALTIMORE AND OHIO-ALTO!\ • Abraham Lincoln Ann Rutledge READ!KC Crusader New YoRK, NEw HAvEN A~'l> HARTFORD Comet BosToN AND MAINE-MAt"£ CeNTRAL Flying Yankee CONCLUSION 68 REPORT ON STREA M LINE, LIGHT-WEIGHT, HIGH-SPEED PASSENGER TRA INS As of June 30, 1938 BY CovERDALE & COLPITTS INTRODUCTION N January 15, 1935, we made a the inauguration ofservice by the Zephyr O report on the performance of and a statement comparing the cost of the first Zephyr type, streamline, operation of the Zephyr with that of the stainless steel, light-weight, high-speed, trains it replaced. -

March Nrhs.Pub

was planned well in a small town so there were some things to do to Paducah Chapter pass the time. Then the overnight National Railway Historical Society hours were spent much like the March 2013 Our Column this month was writ- way out. ten by Tammy Wood ,( Bill Wood’s I know there were people to the lounge car looking for that daughter –in-law), featuring her angry and frustrated by the delay, open booth to play games. Eating perspective of their first trip on however it was out of the hands of in the Dining car was fun also, the Amtrak with family: Amtrak and they did a great job of meals although a little pricey were accommodating us. rather good. First Trip on Amtrak The most enjoyable part about the Making friends with other Tammy Wood trip is being able to travel that dis- kids that sat around us was another tance and really spending time vis- great adventure. They played and Our first trip on Amtrak iting and enjoying the scenery of shared snacks most of the trip out was exciting and a great experi- the mountains instead of navigat- and had different games they made ence. As a mother of three boys it ing them for ourselves. It would up with toys they had brought. As seemed like I would need to in- be worth doing again. clude quite a bit of entertainment, we got closer to Glacier they did however even though we did use look out and watch the scenery some of it they seemed to enjoy some, but this soon lost its spark. -

Chapter 13: North and South, 1820-1860

North and South 1820–1860 Why It Matters At the same time that national spirit and pride were growing throughout the country, a strong sectional rivalry was also developing. Both North and South wanted to further their own economic and political interests. The Impact Today Differences still exist between the regions of the nation but are no longer as sharp. Mass communication and the migration of people from one region to another have lessened the differences. The American Republic to 1877 Video The chapter 13 video, “Young People of the South,” describes what life was like for children in the South. 1826 1834 1837 1820 • The Last of • McCormick • Steel-tipped • U.S. population the Mohicans reaper patented plow invented reaches 10 million published Monroe J.Q. Adams Jackson Van Buren W.H. Harrison 1817–1825 1825–1829 1829–1837 1837–1841 1841 1820 1830 1840 1820 1825 • Antarctica • World’s first public discovered railroad opens in England 384 CHAPTER 13 North and South Compare-and-Contrast Study Foldable Make this foldable to help you analyze the similarities and differences between the development of the North and the South. Step 1 Mark the midpoint of the side edge of a sheet of paper. Draw a mark at the midpoint. Step 2 Turn the paper and fold the outside edges in to touch at the midpoint. Step 3 Turn and label your foldable as shown. Northern Economy & People Economy & People Southern The Oliver Plantation by unknown artist During the mid-1800s, Reading and Writing As you read the chapter, collect and write information under the plantations in southern Louisiana were entire communities in themselves. -

INDEX to VOLUMES 1 and 2

INDEX TO VOLUMES 1 and 2 All contents of publications indexed © 1999, 2000, and 2001 by Kalmbach Publishing Co., Waukesha, Wis. TRAINS CLASSIC 1999 (1 issue) CLASSIC TRAINS Spring 2000 – Winter 2001 (8 issues) 932 pages HOW TO USE THIS INDEX: Feature material has been indexed three or more times—once by the title under which it was published, again under the author’s last name, and finally under one or more of the subject categories or railroads. Photographs standing alone are indexed (usually by railroad), but photographs within a feature article are not separately indexed. Brief items are indexed under the appropriate railroad and/or category. Most references to people are indexed under the company with which they are easily identified; if there is no easy identification, they may be indexed under the per- son’s last name. Items from countries from other than the U.S. and Canada are indexed under the appropriate country. Abbreviations: TC = TRAINS CLASSIC 1999, Sp = Spring CLASSIC TRAINS, Su = Summer CLASSIC TRAINS, Fa = Fall CLASSIC TRAINS, Wi = Winter CLASSIC TRAINS, 00 = 2000, 01 = 2001. Colorado and Beyond, with Dick Kindig, Su00, 50 Tom o r row ’ s Train … Tod a y , Fa00, 80 A Di s p a t c h e r ’s Dilemma, Wi01, 29 Bu f falo Switch, Fa00, 95 Ab b e y , Wallace W., article by: E8 1447 at Grand Central Station, Chicago, Sp00, 106 Bullock, Heaton L., articles by: Class by Itself, TC 14 EM D ’ s Shock Troops, Wi01, 74 Rutland: A Salesman’s Vie w , Wi00, 60 ACF Talgo, Fa00, 86 Ends passenger service on Old Main Line, Wi00, 88 Bumping Post: ACL No. -

Reflections of a White Southerner in the Freedom Struggle Bob Zellner Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee

Volume 2 Living With Others / Crossroads Article 9 2018 Reflections of a White Southerner in the Freedom Struggle Bob Zellner Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee Follow this and additional works at: https://encompass.eku.edu/tcj Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons, Education Commons, Physical Sciences and Mathematics Commons, and the Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Zellner, Bob (2018) "Reflections of a White Southerner in the Freedom Struggle," The Chautauqua Journal: Vol. 2 , Article 9. Available at: https://encompass.eku.edu/tcj/vol2/iss1/9 This Essay is brought to you for free and open access by Encompass. It has been accepted for inclusion in The hC autauqua Journal by an authorized editor of Encompass. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Zellner: Reflections of a White Southerner in the Freedom Struggle BOB ZELLNER REFLECTIONS OF A WHITE SOUTHERNER IN THE FREEDOM STRUGGLE Preamble Eastern Kentucky University's Chautauqua Lecture Series theme, “Living with Others: Challenges and Promises,” certainly resonates with my life, my experiences and my work for human rights. I have found that a proactive approach to living with others provides a strong antidote to close-mindedness, hate and violence. Living with others peacefully, harmoniously and joyfully broadens and liberates one’s life. This sharply contrasts with my Southern upbringing during the forties and fifties, when white supremacy and male chauvinism led many southerners to be narrow minded and reactionary. Juxtaposing challenge with promise, as the Chautauqua theme does, is also compatible with my philosophy of life, relying as I do on dialectics, the unity of opposites and the social gospel. -

![|5Helt%Ri]H LE 20 Mobile Pip 10 Mobile Sudden MARQUIS MENS LOW CUTS, COME 4:50 Changes $2.95](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2374/5helt-ri-h-le-20-mobile-pip-10-mobile-sudden-marquis-mens-low-cuts-come-4-50-changes-2-95-782374.webp)

|5Helt%Ri]H LE 20 Mobile Pip 10 Mobile Sudden MARQUIS MENS LOW CUTS, COME 4:50 Changes $2.95

ONE CENT A WORD ONE CENT A WORD ONE GENT A WORD ONE CENT A WORD RATF.S—One cent a nor«l a bo ad. dayt RATES—Onf cent a word a day! no al. RATES—One pent a word n no ad. HATES—One eenf a nord a dayt no ad. taken for lens than ITio for first Inaer- flays taken for lean than We for first Inaer- tnken fop lean Shan 25c fop flpnt Inner- taken for lean than 25o for first Inser- tlnn. < n«li mm« opcompmir order. tlon. (wh tion mi*m m **»•#»*»» »*«« v «»r«Vf>r mint Nreompmiy order. tlf.ii, rnah moat nppompnny order, j* FOR SALE SALE RENT—ROOMS PERSONAL TALK WITH ALAN JEMISON. _FOR _FOR BALDWIN COUNTY THE AVALON—All outside fur- rooms? U.ADIES^iTooiTTewRrdyT'posTtlveTUguar^ __ 1003 Jeff. Bank Bldg. 8-8-tt Ha^suTna^^Orange ^ / Co. ! nace antee Orchards, 4 to 8 years old, paying $400 to heat; modern conveniences; my great successful E j ——R x g co $1000 per acre per year. Wish' to corre- l moderate price; bath free. 2100 oth remedy; safely relieves some of tne REAL ESTATE. PHONE 7W. with few sub- longest, most obstinate, abnormal oases Barbour spond parties who might I _?v«-___5-25-tf Wants County and io-4-tr scribe for acres in three to five days; no harm, pain or __-_ five each in 100-acre AT THE BIRMINGHAM HOTEfc, steaii? tract in Baldwin to be interference with work; mail. $1.50. FOR RENT OR SALE. -

20 18 Annual Report

20 Annual 18 Report Letter from the Executive Director Executive Committee Elisa Smith Kodish, President I always find myself a little reflective writing the letter for the Annual Jamala Sumaiya McFadden, Vice-President Report. After all, my purpose is to review the previous year. But this William P. Barnette, Treasurer year I feel more reflective than usual, perhaps because it is our 95th Laurice Rutledge Lambert, Secretary year, and our 100th birthday is right around the corner. Lillian Caudle, Immediate Past President Harold Anderson Ironically, what strikes me most is that after all these years, when one Yendelela Neely Holston could imagine Legal Aid might be getting old and stodgy, our advo- Luke A. Lantta cates’ passion and commitment to their work are as strong as ever. Michael T. Nations When I talk to our staff, they always seem to be coming up with new Chad Allan Shultz and exciting projects to benefit our clients. Robert J. Taylor, IV Ryan K. Walsh We have certainly already performed our share of significant and Cristiane R. Wolfe innovative work over the past century. We were the first in the country in home defense, brought the seminal case in disability rights Board of Directors (Olmstead), had the first legal aid project providing for people with Khadijah Abdur-Rahman HIV/AIDS and then for people with cancer, and we began the first Jane Arnold medical-legal collaborative in the southeast with lawyers in Children’s Mary T. Benton Healthcare of Atlanta hospitals. Jacqueline Boatwright-Daus Barbara Carrington But resting on our laurels just isn’t in our DNA! Robert N. -

East Coast Greenway Economic Development from Trails East Coast Greenway

East Coast Greenway Economic Development from Trails East Coast Greenway Connecting 65 million people in communities from Key West, Florida to Calais, Maine 2,900-mile trail linking cities, suburbs, schools, work places, cultural nodes, businesses and transit East Coast Greenway in Maryland 165.75 miles 52.89 miles on trail 3.62 miles in bike lanes 0.7 miles with sharrows 80.08 miles with narrow shoulders 29.55 miles with wide shoulders 27.97 miles of sidewalks Estimated investment to build out = 189 million East Coast Greenway in Maryland Trails create Personal and Community Economic Development Case Study • Silver Comet Trail Economic Impact Analysis and Planning Study. Alta Planning + Design, Econsult Solutions, Robert and Company 61 mile trail 13 miles northwest of Atlanta Connects to 33 mile Chief Ladiga Trail in Alabama Silver Comet Trail Economic Benefit Categories: Direct activity – Direct use results in user spending that benefits local merchants Economic Benefit Categories: Tourism Activity – Direct users can be residents, others are visitors. Expenditures include travel, accommodations, food and entertainment Economic Benefit Categories: Spillover Impacts – As trail use increases, small business and large ramp up operations and increase jobs. New employees spend a portion of earnings locally. Economic Benefit Categories: Unmet Demand – The new and increased demand creates existing business growth and new business opportunities Economic Benefit Categories: Fiscal Impacts – Economic expansions growth tax base Economic Benefit -

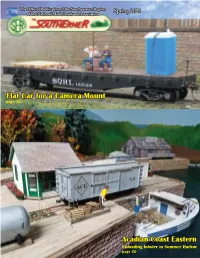

The Southerner Spring 2021

Th e eOffi Offi cial cial Publication Publication of theof theSoutheastern Southeastern Region Region Spring 2021 of the National Model Railroad Association Flat Car for a Camera Mount page 10 Acadian Coast Eastern Unloading lobster in Summer Harbor page 20 nice webinars that I hope you took The President’s Car advantage of, with more coming. Even after the pandemic wanes and in- Larry Burkholder person meetings are again practical, we need to keep virtual meetings and I hope everyone Chairman. His commitment to his clinics in our bag of tricks. It is the is keeping safe division, the SER, and the hobby will best way to bring members spread and getting be missed by all of us. widely in your division together and their Covid-19 maintain their interest. vaccinations SER elections will be held later this as soon as you year, see “Where is my Ballot” below. In 2020 we had a decrease of 98 can. With a successful vaccination Every candidate entered mentions members. Of the 1,139 members at the program, we should be able to get they want to promote more support start of 2021, 79 were new members together again to share our hobby in for regions and divisions. This is an and 22 were Railpass members. person. annual promise, but one that never seems to go very far. It is leadership’s responsibility to Already division sponsored train keep these new and trial members shows in Ashville and Cartersville The truth is that regional and coming back, but each individual have been announced and the division support is primarily a local member can help too by participating prospects for a successful SER responsibility. -

Hearthside Smyrna Senior Apartments

Market Feasibility Analysis HearthSide Smyrna Senior Apartments Smyrna, Cobb County, Georgia Prepared for: OneStreet Residential Effective Date: April 19, 2019 Site Inspection: April 23, 2019 HearthSide Smyrna | Table of Contents TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .................................................................................................... 1 2. INTRODUCTION .............................................................................................................. 8 A. Overview of Subject .............................................................................................................................................. 8 B. Purpose of Report ................................................................................................................................................. 8 C. Format of Report .................................................................................................................................................. 8 D. Client, Intended User, and Intended Use ............................................................................................................. 8 E. Applicable Requirements ...................................................................................................................................... 8 F. Scope of Work ...................................................................................................................................................... 8 G. Report Limitations ............................................................................................................................................... -

2034 Regional Mobility Plan

2009-2034 Knoxville Regional Mobility Plan Knoxville Regional Transportation Planning Organization 2009-2034 Knoxville Regional Mobility Plan Adopted by: East Tennessee South Rural Planning Organization on May 12, 2009 TPO Executive Board on May 27, 2009 This report was funded in part through grant[s] from the Federal Highway Administration and Federal Transit Administration, U.S. Department of Transportation and the Tennessee Department of Transportation. The views and opinions of the authors/ Knoxville Regional Transportation Planning Organization expressed herein do not necessarily state or refl ect those of the U. S. Department of Transportation and Tennessee Department of Transportation. This plan was prepared by: Knoxville Regional Transportation Planning Organization Suite 403, City County Building 400 Main Street Knoxville, TN 37902 Phone: 865-215-2500 Fax: 865-215-2068 Email: [email protected] www.knoxtrans.org 1 Acknowledgements Cover images: “Child in Car” © Charles White/Dreamstime.com “Child on Sidewalk” © Dimitrii/Dreamstime.com “Boy Watching Plane” © Wildcat78/Dreamstime.com “Kid with Bicycle” © Nanmoid/Dreamstime.com 2009-2034 Knoxville Regional Mobility Plan Table of Contents CHAPTER 1: Introduction ................................................................................................................................... 7 Purpose of the 2009 Regional Mobility Plan ......................................................................................... 7 Scope of the Plan ...................................................................................................................................