Draft Environmental Assessment Kalaeloa East Energy Corridor

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Typescript List of Images in Album

Inventory of volume 16. Lady Annie Brassey Photograph Collection, The Huntington Library, San Marino, California Sixteen ..... Page One Ve,rl Dyk~ e~ttached la The originEtl :srass shack which \vas the fi!'st \TolcB.-DO Eouse Hotel,rir.:: of Kiluea voltra.y~.o, islaYlc1 of tlS,;,7aii, 1'1..0.• , TI. ~0hotog., o'Tal 21hot.o n H 5 x 7 • Ib A "{Tolaano ''"1f'intin~, pTob2.. bly Kiluee, by Jules Tavernier* n.d., TI. unouog.,.v, . ~ '" 1_, /S"r X?.2- .... " '" 28. Lgva flow he8.din.:p: tovlarc1s Hj.lo, Hawaj.. ~t perh8/~s 1884 cr 1887 .. n. :0hotog",9 1/8n x 6 3/4n .. 2b Rainbow }I'alls to the rear of the ci ty o~ Hilo, Hawaii, n.d .. , n. 1Jhotog.,9 1/8a x 6 5/8n • 3 !!"odel of a double outrigger canoe and in front a single out:rigger canoe.. Gauoes 8.re c2yllec1 ·VAl,.. ::"l .. d.,. n .. p~","·"ho+oC1" Lr ~.:::>. 'J 9 -"-,,4 X 6 '/R"j '--' .. A v-voman i:1. riding hgbi t caJ..led a E'A 'U--a are.wing either by Bur~ess or Enoch "'iood TlerrJl-. nsd .. , n ~hoto~ 7/St! -~ .. .i::-'-- ~.)., 8" x 4' , , . 4b Native type 'weE':,ri'ng a heed lei of -vvhi te ginger blossoms and a neck lei of the same. The leaves are fragrant and I!luch :?rized even tod.ay called HT:TAII.En., n .. d.., ~J.L.. ~"ho~o~\.) ....1. u t:) .. , 6-"-"2 x Qv 3/11"/, • 'Dosed studio -r,ortrF;..i t of nat:Lve t~.'""0es 8-S they would be sitti.ng at 8. -

Hawai'i State Archives, Geneology #44, Cover Page. Mokuna I Eia Ka

Hawai‘i State Archives, Geneology #44, Cover page. Mokuna I Eia ka lani ke koi pae moku ka lauhulu paoki o ka aina. Hawai‘i State Archives, Geneology #44, page 1 Ka buke kuauhau o na lii a me na kanaka o ka lalani mamuli o ka hanau ana a Kumuhonua. Ka Kane Ka wahine 1 Kumuhonua Haloiho* 2 Ahukai Holehana 3 Kupili Alonainai 4 Kawakupua Heleaeiluna 5 Kawakahiko Kahohaia* 6 Kahikolupa Lukaua 7 Kahikolaikau Kupomakaikaelene* 8 Kahikolaiulu Kanemakaikaelene* 9 Kahikolaihonua Haakoakoaikeaukahonua* 10 Haakoakoalauleia Kaneiakoakanioe 11 Kupo Lanikupo 12 Nahaeikekaua Haneeiluna(Hanuiluna)* 13 Keakenui Laheamanu 14 Kahianahinakiiakea Luahinakii 15 Koluana Hana 16 Lima'na Onoana* 17 Hikuana* Waluana 18 Iwaana Lohanahinakiipapa 19 Welawahilaninui Owe 20 Kahiko Kupulanakehau 21 Wakea Papa He pono kakou e kamailio iki ma keia wahi, no ka mea, mai ka wa o Kumuhonua i hai ia aeneimaluna a hiki i ka wa o Wakoa, aole i hanau he kaikamahine, a i ka noho ana o Wakea ma laua o Papa, alaila e ike auanei kakou ua hanau ka laua keiki he kaikamahine oia hoi o Hoohokukalani, aka ma ka moolelo o keia pae moku hookahi no keia wahine mai ka wa o Kumuhonua mai no a ua kapaia oia o Kauahulihonua, o Papa kahi. A ma keia Hawai‘i State Archives, Geneology #44, page 2 wahi e ike ai kakou ua hanau o Hoohokukalani he wahine o Wakeano nae ke kane. Kane Wahine 1 Wakea Hoohokukalani 2 Haloa Hinamanouluae 3 Waiakalani Huhune 4 Hinanalo Haunuu 5 Nakehili Haulani 6 Wailoa Hikopuanea 7 Kio Kamole 8 Ole Hai Ma keia wahi e kamailio hou kakou no Ole a me Hai * i haiia aela maluna, no ka mea, mai ka wa o Kumuhonua a hiki i ka wa o Ole a me Hai *, aole he wahine–e hookahi noia wahine, o ka wahine no kakou i kamailio pu mai nei ma kela aoao, e waiho iki kakoua mahope aku alaila e hoopiha kakou ma keia i kona kamailio ana. -

South Pacific Beats PDF

Connected South Pacific Beats Level 3 by Veronika Meduna 2018 Overview This article describes how Wellington designer Rachael Hall developed a modern version of the traditional Tongan lali. Called Patō, Rachael’s drum keeps the traditional sound of a lali but incorporates digital capabilities. Her hope is that Patō will allow musicians to mix traditional Pacific sounds with modern music. A Google Slides version of this article is available at www.connected.tki.org.nz This text also has additional digital content, which is available online at www.connected.tki.org.nz Curriculum contexts SCIENCE: Physical World: Physical inquiry and Key Nature of science ideas physics concepts Sound is a form of energy that, like all other forms of energy, can be transferred or transformed into other types of energy. Level 3 – Explore, describe, and represent patterns and trends for everyday examples of physical phenomena, Sound is caused by vibrations of particles in a medium (solid, such as movement, forces … sound, waves … For liquid, or gas). example, identify and describe the effect of forces (contact Sound waves can be described by their wavelength, frequency, and non-contact) on the motion of objects … and amplitude. The pitch of a sound is related to the wavelength and frequency – Science capabilities long or large vibrating objects tend to produce low sounds; short or small vibrating objects tend to produce high sounds. This article provides opportunities to focus on the following science capabilities: The volume of a sound depends on how much energy is used to create the sound – louder sounds have a bigger amplitude but the Use evidence frequency and pitch will be the same whether a given sound is Engage with science. -

Kiva Street Master Inventory Short 1 10/12/2016 1:54:22 PM Kiva Street Master Inventory

10/12/2016 1:54:22 PM Kiva Street Master Inventory Street Name Location . ALAHULA ST KIHEI . KAMA ST WAILUKU . KEAWE ST LAHAINA . KUHINIA ST WAILUKU . NAIO PL KAPALUA . PULELEHUA ST KAPALUA + KILOU PL WAIEHU A PULEHU RD KEAHUA/PUUNENE AAAHI ST WAIKAPU AAHI PL MOLOKAI AALA PL MAKAWAO AALELE ST KAHULUI AIRPORT AALII WAY LAHAINA AAPUEO PKWY PUKALANI AE PL LOWER PAIA AEA PL LAHAINA AEKAI PL LAHAINA AELOA RD PUKALANI AEWA PL PUKALANI AHA ST LANAI AHAAINA WAY KIHEI AHAIKI ST KIHEI AHAKEA ST LANAI AHEAHE PL PUKALANI AHEKOLO PL KIHEI AHEKOLO ST KIHEI AHINA PL MAKAWAO AHINAHINA PL KULA AHIU RD MOLOKAI AHOLEHOLE MAKENA AHOLO RD LAHAINA AHONUI PL PAUWELA AHUA RD PEAHI AHUALANI PL MAKAWAO AHULUA PL KULA AHULUA ST KULA AHUULA PL KIHEI AHUWALE PL MAKAWAO AI KAU ST WAIEHU AI ST MAKAWAO Kiva Street Master Inventory Short 1 10/12/2016 1:54:22 PM Kiva Street Master Inventory Street Name Location AIA PL NAPILI AIAI ST KAHULUI AIKANE PL KOKOMO AILANA PL KIHEI AILOA ST MOLOKAI AILUNA ST MOLOKAI AINA LANI DR PUKALANI AINA MAHIAI PL LAHAINA AINA MAHIAI ST LAHAINA AINA MANU ST MAKAWAO AINA O KANE LANE KAHULUI AINA PL KIHEI AINAHOU PL WAILUKU AINAKEA RD LAHAINA AINAKULA RD KULA AINAOLA ST WAILUKU AINOA ST MOLOKAI AIPUNI ST LAHAINA AKA PL MOLOKAI AKAAKA ST HALIIMAILE AKAHAI PL PAUWELA AKAHELE ST LAHAINA AKAHI PL LANAI AKAI ST KIHEI AKAIKI PL WAILUKU AKAKE ST WAIEHU AKAKUU PL WAILUKU AKAKUU ST WAILUKU AKALA DR KIHEI AKALANI LOOP PUKALANI AKALEI PL KAHULUI AKALEWA PL KIHEI AKAULA WAY WAILEA AKEA PL KULA AKEALAMA CIR KULA AKEKE PL LAHAINA AKEU PL KIHEI AKEU WAY KALAE, -

Microsoftxwordx ... Gexversjonenxx20.06.07.Pdf

The Consequences of Eating With Men Hawaiian Women and the Challenges of Cultural Transformation By Paulina Natalia Dudzinska A thesis submitted for the Cand. Philol. Degree in History of Religions Department of Culture Studies and Oriental Languages University of Oslo Spring 2007 2 Summary Before 1819 Hawaiian society was ruled by a system of ritual laws called kapu. One of these, the aikapu (sacred eating), required men and women to eat separately. Because eating was ritual, some food items, symbolically associated with male deities, were forbidden to women. It was believed that women had a “haumia” (traditionally translated as “defiling”) effect on the male manifestations of the divine and were, as a consequence, barred from direct worship of male gods and work tasks such as agriculture and cooking. In Western history writing, Hawaiian women always presented a certain paradox. Although submitted to aikapu ideology, that was considered devaluing by Western historians, women were nevertheless always present in public affairs. They engaged in the same activities as men, often together with men. They practised sports, went to war and assumed public leadership roles competing with men for power. Ruling queens and other powerful chiefesses appear frequently in Hawaiian history, chants and myths. The Hawaiians did not seem to expect different behaviour of men and women, except perhaps in ritual contexts. Rank transcended any potential asymmetry of genders and sometimes the highest-ranking women were considered above the kapu system, even the aikapu. In 1819, after 40 years of contact with the foreigners, powerful Hawaiian queens decided to abolish the kapu system, including the aikapu. -

'Āinahau: the Genealogy of Ka'iulani's Banyan

ralph thomas kam The Legacy of ‘Āinahau: The Genealogy of Ka‘iulani’s Banyan “And I, in her dear banyan shade, Look vainly for my little maid.” —Robert Louis Stevenson ‘Āinahau, the home of Archibald Scott Cleghorn, his wife, Princess Miriam Kapili Likelike and their daughter, Princess Victoria Ka‘iu- lani, no longer stands, the victim of the transformation of Waikīkī from the playground of royalty to a place of package tours, but one storied piece of its history continues to literally spread its roots through time in the form of the ‘Āinahau banyan. The ‘Āinahau ban- yan has inspired poets, generated controversy and influenced leg- islation. Hundreds of individuals have rallied to help preserve the ‘Āinahau banyan and its numerous descendants. It is fitting that Archibald Cleghorn (15 November 1835–1 Novem- ber 1910), brought the banyan to Hawai‘i, for the businessman con- tinued the legacy of the traders from whom the banyan derives it etymology. The word banyan comes from the Sanskrit “vaniyo” and originally applied to a particular tree of this species near which the traders had built a booth. The botanical name for the East Indian fig tree, ficus benghalensis, refers to the northeast Indian province of Ralph Kam holds an M.A. and a Ph.D. in American Sudies from the University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa and an M.A. in Public Relations from the University of Southern California. The Hawaiian Journal of History, vol. 45 (2011) 49 50 the hawaiian journal of history Bengal, now split between India and Bangladesh. That the tree was introduced in Hawai‘i after Western contact is reflected in its Hawai- ian name: “paniana,” a transliteration of the English word. -

9002 Genealogy 2 Lillian Kekoolani EXCEL

Kekoolani Family Genealogy No. 2 The Second Chiefly Lineage of Lillian Kaeo Kanakaole Kekoolani and her Great Grandchildren 98 Generations This genealogy is similar to Genealogy No. 1, The First Chiefly Genealogy of Lillian Kanakaole Kaeo Kekoolani. It is the same up to generation 67. There it branches off and follows the lineage of the Maui high chiefs and kings, until rejoining Genealogy No. 1 at Generation 89 (Makakkaualii). The generations in our genealogies are calculated at 25 years each. This is a Maui and Big Island genealogy so in the time before Wakea and Papa, the generations are given as they appear in the Kumulipo Chant, the most esteemed genealogy in the eyes of these chiefs. Na Makuakane (Father) Na Makuahine (Mother) Na Keiki (Child) From the Kumulipo Genealogy (Beginning in the Kumulipo Chant at line 1713) 1 513 B.C. Kumuhonua Haloiho Ahukai (Kaloiho) 2 488 B.C. Ahukai Holehana Kapili 3 463 B.C. Kapili Alonainai Kawakupua 4 438 B.C. Kawakupua Heleaeiluna Kawakahiko 5 413 B.C. Kawakahiko Kahohaia Kahikolupa 6 388 B.C. Kahikolupa Lukaua Kahikoleikau 7 363 B.C. Kahikoleikau Kupomakaikaelene Kahikoleiulu 8 338 B.C. Kahikoleiulu Kanemakaikaelene Kahikoleihonua 9 313 B.C. Kahikoleihonua Haakookeau Haakoakoalaulani 10 288 B.C. Haakoakoalaulani Kaneiakoakanioe Kupo 11 263 B.C. Kupo Lanikupo Nahaeikekua 12 238 B.C. Nahaeikekua Hanailuna Keakenui 13 213 B.C. Keakenui Laheamanu Kahianahinakii-Akea 14 188 B.C. Kahianahinakii-Akea Luanahinakiipapa Koluanahinakii 15 163 B.C. Koluanahinakii Hanahina Limanahinakii 9002 Genealogy 2 Lillian Kekoolani EXCEL Corrected Version edited, revised and reset by Dean Kekoolani (12-19-2007) Page 1 of 16 Uncorrected version submitted to the LDS Family History Center (Kalihi, Honolulu) by Alberta Nalimu Harris (1997) Kekoolani Family Genealogy No. -

2019 O'ahu Bike Plan Update

Department of Transportation Services City and County of Honolulu December 2019 This report was funded in part through grants from the Federal Highway Administration and Federal Transit Administration, U.S. Department of Transportation. The views and opinions of the agency expressed herein do not necessarily state or reflect those of the U.S. Department of Transportation. Prepared by City and County of Honolulu, Department of Transportation Services in cooperation with the O‘ahu Metropolitan Planning Organization and the United States Department of Transportation. Consultant Team: HHF Planners, Honolulu, HI in association with Toole Design, Portland Oregon The Authors would like to acknowledge the leadership and contributions provided by the City’s Bicycle Coordinator and the Technical Advisory Committee. TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter 1: Introduction 1-1 1.1: Planning and policy context 1-2 1.2: Existing bicycling conditions 1-4 1.3: Why should we invest in bicycling? 1-6 1.4: Plan Organization 1-8 Chapter 2: Planning Process 2-1 2.1: Honolulu Complete Streets 2-2 2.2: A focus on “interested but concerned” riders 2-3 2.3: What we heard from you 2-4 Chapter 3: Key Recommendations 3-1 3.1: Commit to Vision Zero 3-2 3.2: Develop Seamless connections between bikes and transit 3-4 3.3: Expand encouragement and education efforts 3-6 3.4: Establish a comprehensive bikeway maintenance program 3-8 3.5: Implement a Consistent signage and wayfinding program 3-10 3.6: Evaluate Bicycle Facilities and Programs 3-11 Chapter 4: Proposed -

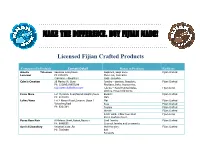

Make the Difference. Buy Fijian Made! ……………………………………………………….…

…….…………………………………………………....…. MAKE THE DIFFERENCE. BUY FIJIAN MADE! ……………………………………………………….…. Licensed Fijian Crafted Products Companies/Individuals Contact Detail Range of Products Emblems Amelia Yalosavu Sawarua Lokia,Rewa Saqamoli, Saqa Vonu Fijian Crafted Lesumai Ph:8332375 Mua i rua, Ramrama (Sainiana – daughter) Saqa -gusudua Cabe’s Creation 20 Marino St, Suva Jewelry - earrings, Bracelets, Fijian Crafted Ph: 3318953/9955299 Necklace, Belts, Accessories. [email protected] Fabrics – Hand Painted Sulus, Fijian Sewn Clothes, Household Items Finau Mara Lot 15,Salato Road,Namdi Heights,Suva Baskets Fijian Crafted Ph: 9232830 Mats Lolive Vana Lot 2 Navani Road,Suvavou Stage 1 Mat Fijian Crafted Votualevu,Nadi Kuta Fijian Crafted Ph: 9267384 Topiary Fijian Crafted Wreath Fijian Crafted Patch work- Pillow Case Bed Fijian Sewn Sheet Cushion Cover. Paras Ram Nair 6 Matana Street,Nakasi,Nausori Shell Jewelry Fijian Crafted Ph: 9049555 Coconut Jewelry and ornaments Seniloli Jewellery Veiseisei,Vuda ,Ba Wall Hanging Fijian Crafted Ph: 7103989 Belt Pendants Makrava Luise Lot 4,Korovuba Street,Nakasi Hand Bags Fijian Crafted Ph: 3411410/7850809 Fans [email protected] Flowers Selai Buasala Karova Settlement,Laucala bay Masi Fijian Crafted Ph:9213561 Senijiuri Tagi c/-Box 882, Nausori Iri-Buli Fijian Crafted Vai’ala Teruka Veisari Baskets, Place Mats Fijian Crafted Ph:9262668/3391058 Laundary Baskets Trays and Fruit baskets Jonaji Cama Vishnu Deo Road, Nakasi Carving – War clubs, Tanoa, Fijian Crafted PH: 8699986 Oil dish, Fruit Bowl Unik -

Kapa'a, Waipouli, Olohena, Wailua and Hanamā'ulu Island of Kaua'i

CULTURAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT FOR THE KAPA‘A RELIEF ROUTE; KAPA‘A, WAIPOULI, OLOHENA, WAILUA AND HANAMĀ‘ULU ISLAND OF KAUA‘I by K. W. Bushnell, B.A. David Shideler, M.A. and Hallett H. Hammatt, PhD. Prepared for Kimura International by Cultural Surveys Hawai‘i, Inc. May 2004 Acknowledgements ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Cultural Surveys Hawai‘i wishes to acknowledge, first and foremost, the kūpuna who willingly took the time to be interviewed and graciously shared their mana‘o: Raymond Aiu, Valentine Ako, George Hiyane, Kehaulani Kekua, Beverly Muraoka, Alice Paik, and Walter (Freckles) Smith Jr. Special thanks also go to several individuals who shared information for the completion of this report including Randy Wichman, Isaac Kaiu, Kemamo Hookano, Aletha Kaohi, LaFrance Kapaka-Arboleda, Sabra Kauka, Linda Moriarty, George Mukai, Jo Prigge, Healani Trembath, Martha Yent, Jiro Yukimura, Joanne Yukimura, and Taka Sokei. Interviews were conducted by Tina Bushnell. Background research was carried out by Tina Bushnell, Dr. Vicki Creed and David Shideler. Acknowledgements also go to Mary Requilman of the Kaua‘i Historical Society and the Bishop Museum Archives staff who were helpful in navigating their respective collections for maps and photographs. Table of Contents TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION............................................................................................................. 1 A. Scope of Work............................................................................................................ 1 B. Methods...................................................................................................................... -

2. the Sinclairs of Pigeon Bay, Or ‘The Prehistory of the Robinsons of Ni’Ihau’: an Essay in Historiography, Or ‘Tales Their Mother Told Them’

2. The Sinclairs Of Pigeon Bay, or ‘The Prehistory of the Robinsons of Ni’ihau’: An essay in historiography, or ‘tales their mother told them’ Of the haole (i.e. European) settler dynasties of Hawai’i there is none grander than that of the Robinsons of the island of Ni’ihau and of Makaweli estate on neighbouring Kauai, 24 kilometres away, across the Kaulakahu Channel. The family is pre-eminent in its long occupancy of its lands, in the lofty distance that it maintains from the outside community and in its inventive ennobling of its past. It has owned Ni’ihau since 1864 and, increasingly from the 1880s, when a new generation led by Aubrey Robinson assumed control of the family’s ranching and planting operations, it has stringently discouraged visitors. Elsewhere in Hawai’i there is generally accepted public access to beaches below the high water or vegetation line, but—to the chagrin of some citizens—that is not so on Ni’ihau. There, according to the Robinsons, claiming the traditional rights of konohiki, or chiefly agents, private ownership extends at least as far as the low-water mark.1 Not surprisingly, this intense isolation has attracted considerable curiosity and controversy, not least because the island contains the last community of native-speaking Hawai’ians, which numbered 190 in 1998.2 Philosophical and moral questions have arisen among commentators determined to find profound meanings in the way the Ni’ihauns’ lives are strictly regulated (the use of liquor and tobacco, for instance, are forbidden) and their extra- insular contacts are restricted. -

Table 4. Hawaiian Newspaper Sources

OCS Study BOEM 2017-022 A ‘Ikena I Kai (Seaward Viewsheds): Inventory of Terrestrial Properties for Assessment of Marine Viewsheds on the Main Eight Hawaiian Islands U.S. Department of the Interior Bureau of Ocean Energy Management Pacific OCS Region August 18, 2017 Cover image: Viewshed among the Hawaiian Islands. (Trisha Kehaulani Watson © 2014 All rights reserved) OCS Study BOEM 2017-022 Nā ‘Ikena I Kai (Seaward Viewsheds): Inventory of Terrestrial Properties for Assessment of Marine Viewsheds on the Eight Main Hawaiian Islands Authors T. Watson K. Ho‘omanawanui R. Thurman B. Thao K. Boyne Prepared under BOEM Interagency Agreement M13PG00018 By Honua Consulting 4348 Wai‘alae Avenue #254 Honolulu, Hawai‘i 96816 U.S. Department of the Interior Bureau of Ocean Energy Management Pacific OCS Region August 18, 2016 DISCLAIMER This study was funded, in part, by the US Department of the Interior, Bureau of Ocean Energy Management, Environmental Studies Program, Washington, DC, through Interagency Agreement Number M13PG00018 with the US Department of Commerce, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Office of National Marine Sanctuaries. This report has been technically reviewed by the ONMS and the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management (BOEM) and has been approved for publication. The views and conclusions contained in this document are those of the authors and should not be interpreted as representing the opinions or policies of the US Government, nor does mention of trade names or commercial products constitute endorsement or recommendation for use. REPORT AVAILABILITY To download a PDF file of this report, go to the US Department of the Interior, Bureau of Ocean Energy Management, Environmental Studies Program Information System website and search on OCS Study BOEM 2017-022.