Asynchronous Evolution of Interdependent Nest Characters Across the Avian Phylogeny

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dieter Thomas Tietze Editor How They Arise, Modify and Vanish

Fascinating Life Sciences Dieter Thomas Tietze Editor Bird Species How They Arise, Modify and Vanish Fascinating Life Sciences This interdisciplinary series brings together the most essential and captivating topics in the life sciences. They range from the plant sciences to zoology, from the microbiome to macrobiome, and from basic biology to biotechnology. The series not only highlights fascinating research; it also discusses major challenges associated with the life sciences and related disciplines and outlines future research directions. Individual volumes provide in-depth information, are richly illustrated with photographs, illustrations, and maps, and feature suggestions for further reading or glossaries where appropriate. Interested researchers in all areas of the life sciences, as well as biology enthusiasts, will find the series’ interdisciplinary focus and highly readable volumes especially appealing. More information about this series at http://www.springer.com/series/15408 Dieter Thomas Tietze Editor Bird Species How They Arise, Modify and Vanish Editor Dieter Thomas Tietze Natural History Museum Basel Basel, Switzerland ISSN 2509-6745 ISSN 2509-6753 (electronic) Fascinating Life Sciences ISBN 978-3-319-91688-0 ISBN 978-3-319-91689-7 (eBook) https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-91689-7 Library of Congress Control Number: 2018948152 © The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s) 2018. This book is an open access publication. Open Access This book is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made. -

AOU Classification Committee – North and Middle America

AOU Classification Committee – North and Middle America Proposal Set 2016-C No. Page Title 01 02 Change the English name of Alauda arvensis to Eurasian Skylark 02 06 Recognize Lilian’s Meadowlark Sturnella lilianae as a separate species from S. magna 03 20 Change the English name of Euplectes franciscanus to Northern Red Bishop 04 25 Transfer Sandhill Crane Grus canadensis to Antigone 05 29 Add Rufous-necked Wood-Rail Aramides axillaris to the U.S. list 06 31 Revise our higher-level linear sequence as follows: (a) Move Strigiformes to precede Trogoniformes; (b) Move Accipitriformes to precede Strigiformes; (c) Move Gaviiformes to precede Procellariiformes; (d) Move Eurypygiformes and Phaethontiformes to precede Gaviiformes; (e) Reverse the linear sequence of Podicipediformes and Phoenicopteriformes; (f) Move Pterocliformes and Columbiformes to follow Podicipediformes; (g) Move Cuculiformes, Caprimulgiformes, and Apodiformes to follow Columbiformes; and (h) Move Charadriiformes and Gruiformes to precede Eurypygiformes 07 45 Transfer Neocrex to Mustelirallus 08 48 (a) Split Ardenna from Puffinus, and (b) Revise the linear sequence of species of Ardenna 09 51 Separate Cathartiformes from Accipitriformes 10 58 Recognize Colibri cyanotus as a separate species from C. thalassinus 11 61 Change the English name “Brush-Finch” to “Brushfinch” 12 62 Change the English name of Ramphastos ambiguus 13 63 Split Plain Wren Cantorchilus modestus into three species 14 71 Recognize the genus Cercomacroides (Thamnophilidae) 15 74 Split Oceanodroma cheimomnestes and O. socorroensis from Leach’s Storm- Petrel O. leucorhoa 2016-C-1 N&MA Classification Committee p. 453 Change the English name of Alauda arvensis to Eurasian Skylark There are a dizzying number of larks (Alaudidae) worldwide and a first-time visitor to Africa or Mongolia might confront 10 or more species across several genera. -

An Update of Wallacels Zoogeographic Regions of the World

REPORTS To examine the temporal profile of ChC produc- specification of a distinct, and probably the last, 3. G. A. Ascoli et al., Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 9, 557 (2008). tion and their correlation to laminar deployment, cohort in this lineage—the ChCs. 4. J. Szentágothai, M. A. Arbib, Neurosci. Res. Program Bull. 12, 305 (1974). we injected a single pulse of BrdU into pregnant A recent study demonstrated that progeni- CreER 5. P. Somogyi, Brain Res. 136, 345 (1977). Nkx2.1 ;Ai9 females at successive days be- tors below the ventral wall of the lateral ventricle 6. L. Sussel, O. Marin, S. Kimura, J. L. Rubenstein, tween E15 and P1 to label mitotic progenitors, (i.e., VGZ) of human infants give rise to a medial Development 126, 3359 (1999). each paired with a pulse of tamoxifen at E17 to migratory stream destined to the ventral mPFC 7. S. J. Butt et al., Neuron 59, 722 (2008). + 18 8. H. Taniguchi et al., Neuron 71, 995 (2011). label NKX2.1 cells (Fig. 3A). We first quanti- ( ). Despite species differences in the develop- 9. L. Madisen et al., Nat. Neurosci. 13, 133 (2010). fied the fraction of L2 ChCs (identified by mor- mental timing of corticogenesis, this study and 10. J. Szabadics et al., Science 311, 233 (2006). + phology) in mPFC that were also BrdU+. Although our findings raise the possibility that the NKX2.1 11. A. Woodruff, Q. Xu, S. A. Anderson, R. Yuste, Front. there was ChC production by E15, consistent progenitors in VGZ and their extended neurogenesis Neural Circuits 3, 15 (2009). -

Verbalizing Phylogenomic Conflict: Representation of Node Congruence Across Competing Reconstructions of the Neoavian Explosion

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/233973; this version posted December 14, 2017. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC 4.0 International license. 1 Tempe, December 12, 2017 RESEARCH ARTICLE (1st submission) Verbalizing phylogenomic conflict: Representation of node congruence across competing reconstructions of the neoavian explosion Nico M. Franz1*, Lukas J. Musher2, Joseph W. Brown3, Shizhuo Yu4, Bertram Ludäscher5 1 School of Life Sciences, Arizona State University, Tempe, Arizona, United States of America 2 Richard Gilder Graduate School and Department of Ornithology, American Museum of Natural History, New York, New York, United States of America 3 Department of Animal and Plant Sciences, University of Sheffield, Sheffield, United Kingdom 4 Department of Computer Science, University of California at Davis, Davis, California, United States of America 5 School of Information Sciences, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, Champaign, Illinois, United States of America * Corresponding author E-mail: [email protected] Short title: Verbalizing phylogenomic conflict Abstract Phylogenomic research is accelerating the publication of landmark studies that aim to resolve deep divergences of major organismal groups. Meanwhile, systems for identifying and integrating the novel products of phylogenomic inference – such as newly supported clade concepts – have not kept pace. However, the ability to verbalize both node concept congruence and conflict across multiple, (in effect) simultaneously endorsed phylogenomic hypotheses, is a critical prerequisite for building synthetic data environments for biological systematics, thereby also benefitting other domains impacted by these (conflicting) inferences. -

A Model of Avian Genome Evolution

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/034710; this version posted April 30, 2016. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license. A Model of Avian Genome Evolution LiaoFu LUO Faculty of Physical Science and Technology, Inner Mongolia University, Hohhot 010021, China email: [email protected] Abstract Based on the reconstruction of evolutionary tree for avian genome a model of genome evolution is proposed. The importance of k-mer frequency in determining the character divergence among avian species is demonstrated. The classical evolutionary equation is written in terms of nucleotide frequencies of the genome varying in time. The evolution is described by a second-order differential equation. The diversity and the environmental potential play dominant role on the genome evolution. Environmental potential parameters, evolutionary inertial parameter and dissipation parameter are estimated by avian genomic data. To describe the speciation event the quantum evolutionary equation is proposed which is the generalization of the classical equation through correspondence principle. The Schrodinger wave function is the probability amplitude of nucleotide frequencies. The discreteness of quantum state is deduced and the ground-state wave function of avian genome is obtained. As the evolutionary inertia decreasing the classical phase of evolution is transformed into quantum phase. New species production is described by the quantum transition between discrete quantum states. The quantum transition rate is calculated which provides a clue to understand the law of the rapid post-Cretaceous radiation of neoavian birds. -

Coos, Booms, and Hoots: the Evolution of Closed-Mouth Vocal Behavior in Birds

ORIGINAL ARTICLE doi:10.1111/evo.12988 Coos, booms, and hoots: The evolution of closed-mouth vocal behavior in birds Tobias Riede, 1,2 Chad M. Eliason, 3 Edward H. Miller, 4 Franz Goller, 5 and Julia A. Clarke 3 1Department of Physiology, Midwestern University, Glendale, Arizona 85308 2E-mail: [email protected] 3Department of Geological Sciences, The University of Texas at Austin, Texas 78712 4Department of Biology, Memorial University, St. John’s, Newfoundland and Labrador A1B 3X9, Canada 5Department of Biology, University of Utah, Salt Lake City 84112, Utah Received January 11, 2016 Accepted June 13, 2016 Most birds vocalize with an open beak, but vocalization with a closed beak into an inflating cavity occurs in territorial or courtship displays in disparate species throughout birds. Closed-mouth vocalizations generate resonance conditions that favor low-frequency sounds. By contrast, open-mouth vocalizations cover a wider frequency range. Here we describe closed-mouth vocalizations of birds from functional and morphological perspectives and assess the distribution of closed-mouth vocalizations in birds and related outgroups. Ancestral-state optimizations of body size and vocal behavior indicate that closed-mouth vocalizations are unlikely to be ancestral in birds and have evolved independently at least 16 times within Aves, predominantly in large-bodied lineages. Closed-mouth vocalizations are rare in the small-bodied passerines. In light of these results and body size trends in nonavian dinosaurs, we suggest that the capacity for closed-mouth vocalization was present in at least some extinct nonavian dinosaurs. As in birds, this behavior may have been limited to sexually selected vocal displays, and hence would have co-occurred with open-mouthed vocalizations. -

Whole-Genome Analyses Resolve Early Branches in the Tree of Life of Modern Birds Erich D

AFLOCKOFGENOMES 90. J. F. Storz, J. C. Opazo, F. G. Hoffmann, Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. RESEARCH ARTICLE 66, 469–478 (2013). 91. F. G. Hoffmann, J. F. Storz, T. A. Gorr, J. C. Opazo, Mol. Biol. Evol. 27, 1126–1138 (2010). Whole-genome analyses resolve ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Genome assemblies and annotations of avian genomes in this study are available on the avian phylogenomics website early branches in the tree of life (http://phybirds.genomics.org.cn), GigaDB (http://dx.doi.org/ 10.5524/101000), National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI), and ENSEMBL (NCBI and Ensembl accession numbers of modern birds are provided in table S2). The majority of this study was supported by an internal funding from BGI. In addition, G.Z. was 1 2 3 4,5,6 7 supported by a Marie Curie International Incoming Fellowship Erich D. Jarvis, *† Siavash Mirarab, * Andre J. Aberer, Bo Li, Peter Houde, grant (300837); M.T.P.G. was supported by a Danish National Cai Li,4,6 Simon Y. W. Ho,8 Brant C. Faircloth,9,10 Benoit Nabholz,11 Research Foundation grant (DNRF94) and a Lundbeck Foundation Jason T. Howard,1 Alexander Suh,12 Claudia C. Weber,12 Rute R. da Fonseca,6 grant (R52-A5062); C.L. and Q.L. were partially supported by a 4 4 4 4 7,13 14 Danish Council for Independent Research Grant (10-081390); Jianwen Li, Fang Zhang, Hui Li, Long Zhou, Nitish Narula, Liang Liu, and E.D.J. was supported by the Howard Hughes Medical Institute Ganesh Ganapathy,1 Bastien Boussau,15 Md. -

Avian Genomics : Fledging Into the Wild!

Erschienen in: Journal of Ornithology ; 156 (2015), 4. - S. 851-865 https://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10336-015-1253-y Avian genomics: fledging into the wild! Robert H. S. Kraus1,2 • Michael Wink3 Abstract Next generation sequencing (NGS) technolo- Zusammenfassung gies provide great resources to study bird evolution and avian functional genomics. They also allow for the iden- Die Ornithologie ist im Zeitalter der Genomik ange- tification of suitable high-resolution markers for detailed kommen analyses of the phylogeography of a species or the con- nectivity of migrating birds between breeding and winter- Neue Sequenziertechnologien (Next Generation Sequen- ing populations. This review discusses the application of cing; NGS) ero¨ffnen die Mo¨glichkeit, Evolution und DNA markers for the study of systematics and phylogeny, funktionelle Genomik bei Vo¨geln umfassend zu untersu- but also population genetics and phylogeography. chen. Weiterhin erlaubt die NGS-Technologie, geeignete, Emphasis in this review is on the new methodology of hochauflo¨sende Markersysteme fu¨r Mikrosatelliten und NGS and its use to study avian genomics. The recent Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms (SNPs) zu identifizieren, publication of the first phylogenomic tree of birds based on um detaillierte Analysen zur Phylogeographie einer Art genome data of 48 bird taxa from 34 orders is presented in oder zur Konnektivita¨t von Zugvo¨geln zwischen Brut- und more detail. Winterpopulationen durchzufu¨hren. Dieses Review widmet sich der Anwendung von DNA Markern fu¨r die Erfor- Keywords Next generation sequencing Á Genetics Á schung von Systematik und Phylogenie sowie Populati- Ornithology Á Whole genome Á Phylogenomics Á Single onsgenetik und Phylogeographie. -

The Origin and Diversification of Birds

Current Biology Review The Origin and Diversification of Birds Stephen L. Brusatte1,*, Jingmai K. O’Connor2,*, and Erich D. Jarvis3,4,* 1School of GeoSciences, University of Edinburgh, Grant Institute, King’s Buildings, James Hutton Road, Edinburgh EH9 3FE, UK 2Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing, China 3Department of Neurobiology, Duke University Medical Center, Durham, NC 27710, USA 4Howard Hughes Medical Institute, Chevy Chase, MD 20815, USA *Correspondence: [email protected] (S.L.B.), [email protected] (J.K.O.), [email protected] (E.D.J.) http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2015.08.003 Birds are one of the most recognizable and diverse groups of modern vertebrates. Over the past two de- cades, a wealth of new fossil discoveries and phylogenetic and macroevolutionary studies has transformed our understanding of how birds originated and became so successful. Birds evolved from theropod dino- saurs during the Jurassic (around 165–150 million years ago) and their classic small, lightweight, feathered, and winged body plan was pieced together gradually over tens of millions of years of evolution rather than in one burst of innovation. Early birds diversified throughout the Jurassic and Cretaceous, becoming capable fliers with supercharged growth rates, but were decimated at the end-Cretaceous extinction alongside their close dinosaurian relatives. After the mass extinction, modern birds (members of the avian crown group) explosively diversified, culminating in more than 10,000 species distributed worldwide today. Introduction dinosaurs Dromaeosaurus albertensis or Troodon formosus.This Birds are one of the most conspicuous groups of animals in the clade includes all living birds and extinct taxa, such as Archaeop- modern world. -

Temperature Drives the Evolution and Global Distribution of Avian Eggshell Colour 2

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/559435; this version posted February 24, 2019. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. 1 Temperature drives the evolution and global distribution of avian eggshell colour 2 3 Phillip A. Wisocki1, Patrick Kennelly1, Indira Rojas Rivera1, Phillip Cassey2, Daniel Hanley1* 4 5 1Long Island University – Post, 720 Northern Boulevard, Brookville, NY 11548, USA 6 2School of Earth and Environmental Sciences, University of Adelaide, SA 5005, Australia 7 8 *email: [email protected] 9 The survival of a bird’s egg depends upon their ability to maintain within strict thermal 10 limits. Avian eggshell colours have long been considered a phenotype that can help them stay 11 within these thermal limits, with dark eggs absorbing heat more rapidly than bright eggs. 12 Although long disputed, evidence suggests that darker eggs do increase in temperature more 13 rapidly than lighter eggs, explaining why dark eggs are often considered as a cost to trade- 14 off against crypsis. Although studies have considered whether eggshell colours can confer an 15 adaptive benefit, no study has demonstrated evidence that eggshell colours have actually 16 adapted for this function. This would require data spanning a wide phylogenetic diversity of 17 birds and a global spatial scale. Here we show evidence that darker and browner eggs have 18 indeed evolved in cold climes, and that the thermoregulatory advantage for avian eggs is a 19 stronger selective pressure in cold climates. -

Rapid Laurasian Diversification of a Pantropical Bird Family During The

Ibis (2020), 162, 137–152 doi: 10.1111/ibi.12707 Rapid Laurasian diversification of a pantropical bird family during the Oligocene–Miocene transition CARL H. OLIVEROS,1,2* MICHAEL J. ANDERSEN,3 PETER A. HOSNER,4,7 WILLIAM M. MAUCK III,5,6 FREDERICK H. SHELDON,2 JOEL CRACRAFT5 & ROBERT G. MOYLE1 1Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology and Biodiversity Institute, University of Kansas, Lawrence, KS, USA 2Museum of Natural Science and Department of Biological Sciences, Louisiana State University, Baton Rouge, LA, USA 3Department of Biology and Museum of Southwestern Biology, University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, NM, USA 4Division of Birds, Department of Vertebrate Zoology, National Museum of Natural History, Washington, DC, USA 5Department of Ornithology, American Museum of Natural History, New York, NY, USA 6New York Genome Center, New York, NY, USA 7Natural History Museum of Denmark and Center for Macroecology, Evolution, and Climate; University of Copenhagen, Copenhagen, Denmark Disjunct, pantropical distributions are a common pattern among avian lineages, but dis- entangling multiple scenarios that can produce them requires accurate estimates of his- torical relationships and timescales. Here, we clarify the biogeographical history of the pantropical avian family of trogons (Trogonidae) by re-examining their phylogenetic rela- tionships and divergence times with genome-scale data. We estimated trogon phylogeny by analysing thousands of ultraconserved element (UCE) loci from all extant trogon gen- era with concatenation and coalescent approaches. We then estimated a time frame for trogon diversification using MCMCTree and fossil calibrations, after which we performed ancestral area estimation using BioGeoBEARS. We recovered the first well-resolved hypothesis of relationships among trogon genera. -

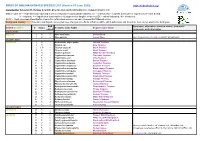

BIRDS of BOLIVIA UPDATED SPECIES LIST (Version 03 June 2020) Compiled By: Sebastian K

BIRDS OF BOLIVIA UPDATED SPECIES LIST (Version 03 June 2020) https://birdsofbolivia.org/ Compiled by: Sebastian K. Herzog, Scientific Director, Asociación Armonía ([email protected]) Status codes: R = residents known/expected to breed in Bolivia (includes partial migrants); (e) = endemic; NB = migrants not known or expected to breed in Bolivia; V = vagrants; H = hypothetical (observations not supported by tangible evidence); EX = extinct/extirpated; IN = introduced SACC = South American Classification Committee (http://www.museum.lsu.edu/~Remsen/SACCBaseline.htm) Background shading = Scientific and English names that have changed since Birds of Bolivia (2016, 2019) publication and thus differ from names used in the field guide BoB Synonyms, alternative common names, taxonomic ORDER / FAMILY # Status Scientific name SACC English name SACC plate # comments, and other notes RHEIFORMES RHEIDAE 1 R 5 Rhea americana Greater Rhea 2 R 5 Rhea pennata Lesser Rhea Rhea tarapacensis , Puna Rhea (BirdLife International) TINAMIFORMES TINAMIDAE 3 R 1 Nothocercus nigrocapillus Hooded Tinamou 4 R 1 Tinamus tao Gray Tinamou 5 H, R 1 Tinamus osgoodi Black Tinamou 6 R 1 Tinamus major Great Tinamou 7 R 1 Tinamus guttatus White-throated Tinamou 8 R 1 Crypturellus cinereus Cinereous Tinamou 9 R 2 Crypturellus soui Little Tinamou 10 R 2 Crypturellus obsoletus Brown Tinamou 11 R 1 Crypturellus undulatus Undulated Tinamou 12 R 2 Crypturellus strigulosus Brazilian Tinamou 13 R 1 Crypturellus atrocapillus Black-capped Tinamou 14 R 2 Crypturellus variegatus