Penn Central Decision

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

LEGEND Location of Facilities on NOAA/NYSDOT Mapping

(! Case 10-T-0139 Hearing Exhibit 2 Page 45 of 50 St. Paul's Episcopal Church and Rectory Downtown Ossining Historic District Highland Cottage (Squire House) Rockland Lake (!304 Old Croton Aqueduct Stevens, H.R., House inholding All Saints Episcopal Church Complex (Church) Jug Tavern All Saints Episcopal Church (Rectory/Old Parish Hall) (!305 Hook Mountain Rockland Lake Scarborough Historic District (!306 LEGEND Nyack Beach Underwater Route Rockefeller Park Preserve Rockefeller Park Preserve Rockefeller Park Preserve CP Railroad ROW Rockefeller Park Preserve Rockefeller Park Preserve CSX Railroad ROW Rockefeller Park Preserve (!307 Rockefeller Park Preserve Rockefeller Park Preserve NYS Canal System, Underground (! Rockefeller Park Preserve Milepost Rockefeller Park Preserve Rockefeller Park Preserve Rockefeller Park Preserve )" Sherman Creek Substation Rockefeller Park Preserve Rockefeller Park Preserve Methodist Episcopal Church at Nyack *# Yonkers Converter Station Rockefeller Park Preserve Upper Nyack Firehouse ^ Mine Rockefeller Park Preserve Van Houten's Landing Historic District (!308 Park Rockefeller Park Preserve Union Church of Pocantico Hills State Park Hopper, Edward, Birthplace and Boyhood Home Philipse Manor Railroad Station Untouched Wilderness Dutch Reformed Church Rockefeller, John D., Estate Historic Site Tappan Zee Playhouse Philipsburg Manor St. Paul's United Methodist Church US Post Office--Nyack Scenic Area Ross-Hand Mansion McCullers, Carson, House Tarrytown Lighthouse (!309 Harden, Edward, Mansion Patriot's Park Foster Memorial A.M.E. Zion Church Irving, Washington, High School Music Hall North Grove Street Historic District DATA SOURCES: NYS DOT, ESRI, NOAA, TDI, TRC, NEW YORK STATE DEPARTMENT OF Christ Episcopal Church Blauvelt Wayside Chapel (Former) First Baptist Church and Rectory ENVIRONMENTAL CONSERVATION (NYDEC), NEW YORK STATE OFFICE OF PARKS RECREATION AND HISTORICAL PRESERVATION (OPRHP) Old Croton Aqueduct Old Croton Aqueduct NOTES: (!310 1. -

Manhattan N.V. Map Guide 18

18 38 Park Row. 113 37 101 Spring St. 56 Washington Square Memorial Arch. 1889·92 MANHATTAN N.V. MAP GUIDE Park Row and B kman St. N. E. corner of Spring and Mercer Sts. Washington Sq. at Fifth A ve. N. Y. Starkweather Stanford White The buildings listed represent ali periods of Nim 38 Little Singer Building. 1907 19 City Hall. 1811 561 Broadway. W side of Broadway at Prince St. First erected in wood, 1876. York architecture. In many casesthe notion of Broadway and Park Row (in City Hall Perk} 57 Washington Mews significant building or "monument" is an Ernest Flagg Mangin and McComb From Fifth Ave. to University PIobetween unfortunate format to adhere to, and a portion of Not a cast iron front. Cur.tain wall is of steel, 20 Criminal Court of the City of New York. Washington Sq. North and E. 8th St. a street or an area of severatblocks is listed. Many glass,and terra cotta. 1872 39 Cable Building. 1894 58 Housesalong Washington Sq. North, Nos. 'buildings which are of historic interest on/y have '52 Chambers St. 1-13. ea. )831. Nos. 21-26.1830 not been listed. Certain new buildings, which have 621 Broadway. Broadway at Houston Sto John Kellum (N.W. corner], Martin Thompson replaced significant works of architecture, have 59 Macdougal Alley been purposefully omitted. Also commissions for 21 Surrogates Court. 1911 McKim, Mead and White 31 Chembers St. at Centre St. Cu/-de-sac from Macdouga/ St. between interiorsonly, such as shops, banks, and 40 Bayard-Condict Building. -

The Bellwether—A Passive House Tower Renews a Public Housing Campus

ctbuh.org/papers Title: The Bellwether—A Passive House Tower Renews a Public Housing Campus Author: Daniel Kaplan, Senior Partner, FXCollaborative Subject: Architectural/Design Keywords: Affordable Housing Density Passive Design Vertical Urbanism Publication Date: 2019 Original Publication: 2019 Chicago 10th World Congress Proceedings - 50 Forward | 50 Back Paper Type: 1. Book chapter/Part chapter 2. Journal paper 3. Conference proceeding 4. Unpublished conference paper 5. Magazine article 6. Unpublished © Council on Tall Buildings and Urban Habitat / Daniel Kaplan The Bellwether—A Passive House Tower Renews a Public Housing Campus Abstract Daniel Kaplan Senior Partner This study examines issues and opportunities around The Bellwether, a 52-story tower located FXCollaborative New York, United States in a 1960s public housing campus in Manhattan. It is the first of the New York City Housing Authority’s “NextGen” program, where perimeter sites are being leased to the private sector to spur mixed-income development. The Bellwether incorporates about 400 apartments and Dan Kaplan, FAIA, LEED AP, is a Senior Partner an outward facing, non-profit athletic facility. Its design skillfully inserts a slender tower in a at FXCollaborative, and serves in a design and “left-over” triangular parcel and in doing so, creates a network of improved open spaces on the leadership capacity for many of the firm’s complex, award-winning urban buildings. Adept at creating campus. About to start construction, the project is planned to be the world’s tallest Passivhaus large-scale, high-performance buildings and tower. The Bellwether is emblematic of the type of creative planning and design needed to repair urban designs, Kaplan approaches each project— and elevate these challenged conditions, resulting in a smarter, greener, better integrated, more from individual buildings to large-scale urban efficient and more humane city. -

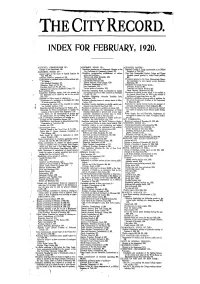

1920-02-00 Index

HE CITY RECORD. INDEX FOR FEBRUARY, 1920. ACCOUNTS, COMMISSIONER OF- ALDERMEN, BOARD OF- APPROVED PAPERS- Changes, in the department, 969. Resolution granting use of Aldermanic Chamber to the Marshall, Charles A., fixing compensation of, as Official ALDERMEN, BOARD OF- City Parliament of Community Council, 723. Examiner of Title, 891. Annual report of the Court of Special Sessions for Resolution recommending establishment of various . New York Homeopathic Medical College and Flower Year 1919, 97$. grades and positions- Hospital, permit granted to collect funds publicly, Aldermen, Board of, sympathy of, 73. Bellevue and Allied Hospitals, 1233. 889. Authorization to purchase various articles without pub- City Departments, 1232. Permission granted to the Oscar Hammerstein Memo- lic letting- City Record, Board of, 1231. rial Association to erect banner across Broadway, Chief Medical Examiner, 721. District Attorney, Kings County, 1230. Manhattan, 891. Education, Board of, 714, 715. Education, Department of, 1231. Resolution for special revenue bonds- Purchase, Board of, 715, 721, 1112. Law Department, 1231. Aldermen, Board of, 887. Supreme Court Library, Richmond County, 715. Various grades of positions, 1232. Committee on General Welfare, 887. ' Board meetings, 651. Resolution requesting Board of Education to explain Street Cleaning, Department of, 886. Comptroller, statement setting forth the, amount by non-payment of bonus to Men Teachers on Schedules Resolution for special revenue bonds, to be credited to law authorized to be raised by tax in the . current VI. and VII., 723. the General School Fund for 1919 to pay salaries of year, 1223. Resolution designating Alexander Hamilton Park, teaching and supervising force, etc., 887. Committee on Rules, report of, relating to-- Manhattan, 1120. -

Municipal Asphalt Plant

Landmarks Preservation Corr~ission January 27, 197 6, Number 2 LP-0905 ~ruNICIPAL ASPHALT PLANT, Between 90th and 9lst Street at the East River Drive, Borough of Hanhattan. Built 1941-44; architect s Ely Jacques Kahn and Robert Allan Jacobs; industri al design by the Department of Borough harks of the Office of the Borough President of Manhattan. Landmark Site: Borough of Manhattan Tax ~lap Block 1587, Lot 1 in part consisting of the land on which the descri bed building is situated. On November 25, 1975, the Landmarks Preservation Commission held a public hearing on the proposed designation as a Landmark of the ~Iunicipal Asphalt Plant and the proposed designation of the related Landmark Site (Item No. 2). The hearing had been duly advertised in accordance with the provisions of la;.;. Fifteen witnesses, including Dr. George Murphy, Chairman of the Neighborhood Committee for Asphalt Green, spoke in favor of designation. Tnere He·re no speakers in opposition to designation. The witnesses favoring designation indicated that there is great support for this designation among the members of the community. The Commission has also received many letters a.11d. other expressions of support for this designation. DESCRIPTION AND .ANALYSIS The Municipal Asphalt Plant, built in 1941-44, was designed by the prominent New York City architects Ely Jacques Kahn and Robert Allan Jacobs for the Office of the Borough President of Manhattan. The asphalt plant originally consisted of the mixing plant--- the main building which is still standi ng--and storage buildings for raw materials which were transported by means of a conveyor to the mixing plant. -

The Radio Urbanism of Robert C. Weinberg, 1966–71 by Christopher Neville for the New York Preservation Archive Project

“Building and Rebuilding New York:” The Radio Urbanism of Robert C. Weinberg, 1966–71 by Christopher Neville for the New York Preservation Archive Project “...This is Robert C. Weinberg, critic-at-large in architecture and planning for WNYC.” Introduction: Robert Weinberg, Department of Parks (under Robert Moses), New York City, and WNYC and at the Department of City Planning. Robert C. Weinberg was an architect and urban planner active in New York from the He taught courses in planning and related early 1930s until his death in 1974. Over four fields at New York University, the Pratt Insti- decades of vigorous engagement with preser- tute, the New School for Social Research, and vation and planning issues, he was both an ac- Yale, and published roughly 150 articles and tive participant in or astute observer of almost reviews. He was also the co-editor, with every major development in New York urban- Henry Fagin, of the important 1958 report, ism. Between 1966 and 1971, near the end of Planning and Community Appearance, jointly his career, he served as radio station WNYC’s sponsored by the New York chapters of the “critic-at-large in architecture and planning,” American Institute of Architects and the and his broadcasts are a window onto his re- American Institute of Planners. markable career and the transformations he But over his long career, Weinberg devoted witnessed in the city he loved. Weinberg’s the bulk of his considerable energies to a long personal history in the trenches and be- broad range of public-spirited efforts covering hind the scenes gave him unique perspective almost every aspect of urban development and on these changes—an insider’s overview, with city life, including historic preservation, zon- a veteran’s hindsight. -

Chapter 2 Description of Facility Sites

CHAPTER 2 DESCRIPTION OF FACILITY SITES 2.1 Introduction 2.1.1 Overview This chapter describes the sites and operations for which the results of environmental reviews are presented in Chapters 4 through 11. Sections 2.2 through 2.9 describe Existing Conditions at each site. Each site description contains a Site Location figure that identifies the approximate boundaries of the site and shows the surrounding neighborhood and a Facility Footprint figure that provides an aerial view of the existing site with a footprint of the facility superimposed on the site. A Cross Section View of the processing building interior is also included. These graphics are provided to facilitate the readers’ understanding of existing site conditions and any changes that would occur with development of the facility. The site description also identifies the approximate distance of residential districts, schools and parks from the site. Zoning maps and other figures or tables that locate the zoning districts, schools, and parks are in the appropriate subsections of the environmental review chapters on each site. The sites under consideration may include multiple parcels under varied ownership and may extend beyond the property boundaries of parcels on which the subject waste transfer facility is located. For purposes of analysis, the primary and related parcels are considered a single entity. All of the Converted MTS sites contain existing MTSs that, in all cases except for Southwest Brooklyn, the existing MTSs will be demolished and replaced with a new MTS that is designated to containerize waste for disposal at out-of-City locations. Three sites also contain existing incinerators—Southwest Brooklyn, Greenpoint, and Hamilton Avenue. -

Index for December, 1946

THE CITY RECORD INDEX FOR DECEMBER, 1946 ART COMMISSION— CITY SHERIFF— COUNCIL, THE— Minutes of meeting held November 13, 1946, 5209. Changes in the department, 5612. General Welfare, Committee on, reports of the— Minutes of special meeting held November 20, 1946, 5210. COMPTROLLER, OFFICE OF THE— In favor of adopting a Local Law to amend the Ad- ASSESSORS, BOARD OF-- Abstract of transactions for weeks ended— ministrative Code of The City of New York, in Completion of assessments— November 16, 1946, 5210. relation to location of sewage disposal plants, 5572, Bronx, Borough of The, 5461. November 23, 1946, 5602. 5601. Brooklyn, Borough of, 5191, 5461. November 30, 1946, 5609. In favor of adopting a Local Law to amend the New Manhattan, Borough of, 5191, 5461. December 7, 1946, 5609 York City Charter, in relation to Deputy Fire Queens, Borough of, 5191. Changes in the department, 5214, 5561. Commissioner, 5572, 5602. Notices to present claims for damages—Notices of hear- Interest on City bonds and stock, 5511. In favor of adopting a Local Law to amend the Ad- Statement of the operations of the several Sinking Funds ministrative Code of The City of New York, rela- Brooklyn, Borough of, 5428. of The City of New York during the month of tive to the license fee imposed on dealers in second- Queens, Borough of, 5497, 5588. November, 1946, 5424. hand articles, 5572, 5602. BOARD MEETINGS, 5189. Statement summarizing the City's cash receipts and dis- In favor of filing a Local Law to amend the Ad- BRONX, PRESIDENT, BOROUGH OF THE— bursements during the month of November, 1946, ministrative Code of The City of New York, in Changes in the department, 5189, 5233, 5487. -

© 2014 Kara Murphy Schlichting ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

© 2014 Kara Murphy Schlichting ALL RIGHTS RESERVED “Among the Ash Heaps and Millionaires”: Shaping New York’s Periphery, 1840-1940 By Kara Murphy Schlichting A dissertation submitted to the Graduate School-New Brunswick Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey In partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Program in History Written Under the direction of Dr. Alison Isenberg And approved by ________________________________________________ ________________________________________________ ________________________________________________ ________________________________________________ ________________________________________________ New Brunswick, New Jersey May 2014 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION “Among the Ash Heaps and Millionaires”: Shaping New York’s Periphery, 1840-1940 By KARA MURPHY SCHLICHTING Dissertation Director: Dr. Alison Isenberg “‘Among the Ash Heaps and Millionaires’” offers a new model for understanding the invention of greater New York. It demonstrates that city-building took place through the collective work of regional actors on the urban edge. To explain New York’s dramatic expansion between 1840 and 1940, this project investigates the city-building work of diverse local actors—real estate developers, amusement park entrepreneurs, neighborhood benefactors, and property owners—in conjunction with the work of planners. Its regional perspective looks past political boundaries to reconsider the dynamic and evolving interconnections between city and suburb in the metropolitan region. Beginning in the mid-19th century, annexed territories served as laboratories for comprehensive planning ideas. In districts lacking powerful boosters, however, amusement park entrepreneurs and summer campers turned undeveloped waterfront into a self-built leisure corridor. The systematic decision-making of local actors produced informal development plans. Estate owners disliked the crowds at nearby working-class resorts; whites blocked black access to leisure amenities. -

SEAGRAM BUILDING, INCWDING the PIAZA, 375 Park Avenue, Manhattan

I.andrnarks Preservation Corrnnission October 3, 1989; resignation List 221 IP-1664 SEAGRAM BUILDING, INCWDING THE PIAZA, 375 Park Avenue, Manhattan. resigned by I.udwig Mies van der Rohe with Philip Johnson; Kahn & Jacobs, associate architects. Built 1956-58. Landmark Site: Borough of Manhattan Tax Map Block 1307, Lot 1. On May 17, 1988, the I.andrnarks Preservation Commission held a public hearing on the proposed designation as a I.andrnark of the Seagram Building including the plaza, and the proposed designation of the related Landmark Site (Item No. 1) . The hearing had been duly advertised in accordance with the pro visions of law. 'IWenty-one witnesses, including a representative of the building's owner, spoke in favor of designation. No witnesses spoke in opposition to designation. The Commission has received many letters in favor of designation. DFSCRIPI'ION AND ANALYSIS Surrnna:ry The Seagram Building, erected in 1956-58, is the only building in New York City designed by architectural master I.udwig Mies van der Rohe. carefully related to the tranquil granite and :marble plaza on its Park Avenue site, the elegant curtain wall of bronze and tinted glass enfolds the first fully modular modern office tower. Constructed at a time when Park Avenue was changing from an exclusive residential thoroughfare to a prestigious business address, the Seagram Building embodies the quest of a successful corporation to establish further its public image through architectural patronage. The president of Joseph E. Seagram & Sons, Samuel Bronfman, with the aid of his daughter Phyllis I.arnbert, carefully selected Mies, assisted by Philip Johnson, to design an office building later regarded by many, including Mies himself, as his crowning work and the apotheosis of International Style towers. -

Appendix EE.09 – Cultural Resources

Appendix EE.09 – Cultural Resources Tier 1 Final EIS Volume 1 NEC FUTURE Appendix EE.09 - Cultural Resources: Data Geography Affected Environment Environmental Consequences Context Area NHL NRHP NRE NHL NRHP NRE NHL NRHP NRE NHL NRHP NRE NHL NRHP NRE NHL NRHP NRE State County Existing NEC including Existing NEC including Existing NEC including Preferred Alternative Preferred Alternative Preferred Alternative Hartford/Springfield Line Hartford/Springfield Line Hartford/Springfield Line DC District of Columbia 10 21 0 10 21 0 0 3 0 0 4 0 49 249 0 54 248 0 MD Prince George's County 0 7 0 0 7 0 0 0 0 0 2 0 1 23 0 1 23 0 MD Anne Arundel County 0 3 0 0 3 0 0 0 0 0 1 0 0 8 0 0 8 0 MD Howard County 0 1 0 0 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 3 0 1 3 0 MD Baltimore County 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 9 0 0 10 0 MD Baltimore City 3 44 0 3 46 0 0 1 0 0 5 0 25 212 0 26 213 0 MD Harford County 0 5 0 0 7 0 0 0 0 0 2 0 1 12 0 1 15 0 MD Cecil County 0 6 2 0 8 2 0 0 2 0 1 2 0 11 2 0 11 2 DE New Castle County 3 64 2 3 67 2 0 2 1 0 5 2 3 187 1 4 186 2 PA Delaware County 0 4 0 1 5 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 18 0 1 18 0 PA Philadelphia County 9 85 1 10 87 1 0 2 1 3 4 1 57 368 1 57 370 1 PA Bucks County 3 8 1 3 8 1 0 1 1 1 1 1 3 15 1 3 15 1 NJ Burlington County 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 17 0 1 17 0 NJ Mercer County 1 9 1 1 10 1 0 0 2 0 0 2 5 40 1 6 40 1 NJ Middlesex County 1 20 2 1 20 2 0 0 1 0 1 1 1 42 2 1 42 2 NJ Somerset County 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 4 0 0 4 0 NJ Union County 1 9 1 1 10 1 0 1 1 0 2 1 2 17 1 2 17 1 NJ Essex County 1 24 1 1 26 1 0 1 1 0 1 1 1 65 1 1 65 1 NJ Hudson County -

THE CITY RECORD. Cr1 ,4 PUBLIC SERVICE COMMISSION, FIRST

THE CITY RECORD. Vol.. XLVII. NUMBER 14064. NEW YORK, TUESDAY, AUGUST 19, 1919. PRICE, 10 CENTS. Brighton ave., and Michael J. Sullivan, July 21; John Vti. Johnston, 56 Morning- THE CITY RECORD. 73 Cleveland st., S. I., Extra Drivers at side ave., at $1,800 per annum, July 22; $1,095.50 per annum, July 21. Louis Baumann, 72 Sand st., S. I., at cr1 ,4 Salaries Fixed—Clerk: Vincent P. Gilli- $1,420 per annum, July 25. OFFICIAL JOURNAL OF THE CITY OF NEW YORK. gan, 20 Stuyvesant st., at $600 per annum, CALVIN D. VAN NAME, President. Published Under Authority of Section 1526, Greater New York Charter. by tbs BOARD OF CITY RECORD. DEPARTMENT OF FINANCE. JOHN F. HYLAN, MAYOR. WILLIAM P. BURR, COIPOIATION COUNSEL CHARLES L CRAIG. Coxniou.n. WARRANTS MADE READY FOR PAYMENT IN DEPORTMENT OF FINANCE PETER J. BRADY, Surravisot. MONDAY, AUGUST 18, 1919. 13elow is a statement of warrants made ready for payment on the above date, Supervisor's Office, Municipal Building, SO floor. showing therein the Department of Finance voucher number, the dates of the invoices Published daily, at 9 a. m., except Sundays and legal holidays. Distributing Division, 125 and 127 Worth st., Manhattan, New York City. or the registered number of the contract, the date the voucher was filed in the Subscription, $20 a year, exclusive of supplements. Daily issue, 10 cents a coot. Department of Finance, the name of the payee and the amount of the warrant. SUPPLEMENTS: Civil Lis. (containing names, salaries, etc.,. of the City employees), $5; Where two or more bills are embraced in the warrant, the dates of the earliest Official Canvass of Votes, $1; Registry Lists, 10 cents each assembly district; Law Department Sup- and latest are given, excepting that, when such payments are made under a contract, plement, $1; Assessed Valuation of Real Estate, $2 each section; postage extra.