© 2014 Kara Murphy Schlichting ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

“From the Cracks in the Sidewalks of NYC”: The

“From the Cracks in the Sidewalks of N.Y.C.”: The Embodied Production of Urban Decline, Survival, and Renewal in New York’s Fiscal-Crisis-Era Streets, 1977-1983 by Elizabeth Healy Matassa B.A. in Italian and French Studies, May 2003, University of Delaware M.A. in Geography, May 2006, Louisiana State University A Dissertation submitted to The Faculty of The Columbian College of Arts and Sciences of The George Washington University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy January 31, 2014 Dissertation directed by Suleiman Osman Associate Professor of American Studies The Columbian College of Arts and Sciences of the George Washington University certifies that Elizabeth Healy Matassa has passed the Final Examination for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy as of August 21, 2013. This is the final and approved form of the dissertation. “From the Cracks in the Sidewalks of N.Y.C.”: The Embodied Production of Decline, Survival, and Renewal in New York’s Fiscal-Crisis-Era Streets, 1977-1983 Elizabeth Healy Matassa Dissertation Research Committee: Suleiman Osman, Associate Professor of American Studies, Dissertation Director Elaine Peña, Associate Professor of American Studies, Committee Member Elizabeth Chacko, Associate Professor of Geography and International Affairs, Committee Member ii ©Copyright 2013 by Elizabeth Healy Matassa All rights reserved iii Dedication The author wishes to dedicate this dissertation to the five boroughs. From Woodlawn to the Rockaways: this one’s for you. iv Abstract of Dissertation “From the Cracks in the Sidewalks of N.Y.C.”: The Embodied Production of Urban Decline, Survival, and Renewal in New York’s Fiscal-Crisis-Era Streets, 1977-1983 This dissertation argues that New York City’s 1970s fiscal crisis was not only an economic crisis, but was also a spatial and embodied one. -

Strategic Policy Statement 2014 Melinda Katz

THE OFFICE OF THE QUEENS BOROUGH PRESIDENT Strategic Policy Statement 2014 Melinda Katz Queens Borough President The Borough of Queens is home to more than 2.3 million residents, representing more than 120 countries and speaking more than 135 languages1. The seamless knit that ties these distinct cultures and transforms them into shared communities is what defines the character of Queens. The Borough’s diverse population continues to steadily grow. Foreign-born residents now represent 48% of the Borough’s population2. Traditional immigrant gateways like Sunnyside, Woodside, Jackson Heights, Elmhurst, Corona, and Flushing are now communities with the highest foreign-born population in the entire city3. Immigrant and Intercultural Services The immigrant population remains largely underserved. This is primarily due to linguistic and cultural barriers. Residents with limited English proficiency now represent 28% of the Borough4, indicating a need for a wide range of social service support and language access to City services. All services should be available in multiple languages, and outreach should be improved so that culturally sensitive programming can be made available. The Borough President is actively working with the Queens General Assembly, a working group organized by the Office of the Queens Borough President, to address many of these issues. Cultural Queens is amidst a cultural transformation. The Borough is home to some of the most iconic buildings and structures in the world, including the globally recognized Unisphere and New York State Pavilion. Areas like Astoria and Long Island City are establishing themselves as major cultural hubs. In early 2014, the New York City Council designated the area surrounding Kaufman Astoria Studios as the city’s first arts district through a City Council Proclamation The areas unique mix of adaptively reused residential, commercial, and manufacturing buildings serve as a catalyst for growth in culture and the arts. -

Aqueduct Racetrack Is “The Big Race Place”

Table of Contents Chapter 1: Welcome to The New York Racing Association ......................................................3 Chapter 2: My NYRA by Richard Migliore ................................................................................6 Chapter 3: At Belmont Park, Nothing Matters but the Horse and the Test at Hand .............7 Chapter 4: The Belmont Stakes: Heartbeat of Racing, Heartbeat of New York ......................9 Chapter 5: Against the Odds, Saratoga Gets a Race Course for the Ages ............................11 Chapter 6: Day in the Life of a Jockey: Bill Hartack - 1964 ....................................................13 Chapter 7: Day in the Life of a Jockey: Taylor Rice - Today ...................................................14 Chapter 8: In The Travers Stakes, There is No “Typical” .........................................................15 Chapter 9: Our Culture: What Makes Us Special ....................................................................18 Chapter 10: Aqueduct Racetrack is “The Big Race Place” .........................................................20 Chapter 11: NYRA Goes to the Movies .......................................................................................22 Chapter 12: Building a Bright Future ..........................................................................................24 Contributors ................................................................................................................26 Chapter 1 Welcome to The New York Racing Association On a -

LEGEND Location of Facilities on NOAA/NYSDOT Mapping

(! Case 10-T-0139 Hearing Exhibit 2 Page 45 of 50 St. Paul's Episcopal Church and Rectory Downtown Ossining Historic District Highland Cottage (Squire House) Rockland Lake (!304 Old Croton Aqueduct Stevens, H.R., House inholding All Saints Episcopal Church Complex (Church) Jug Tavern All Saints Episcopal Church (Rectory/Old Parish Hall) (!305 Hook Mountain Rockland Lake Scarborough Historic District (!306 LEGEND Nyack Beach Underwater Route Rockefeller Park Preserve Rockefeller Park Preserve Rockefeller Park Preserve CP Railroad ROW Rockefeller Park Preserve Rockefeller Park Preserve CSX Railroad ROW Rockefeller Park Preserve (!307 Rockefeller Park Preserve Rockefeller Park Preserve NYS Canal System, Underground (! Rockefeller Park Preserve Milepost Rockefeller Park Preserve Rockefeller Park Preserve Rockefeller Park Preserve )" Sherman Creek Substation Rockefeller Park Preserve Rockefeller Park Preserve Methodist Episcopal Church at Nyack *# Yonkers Converter Station Rockefeller Park Preserve Upper Nyack Firehouse ^ Mine Rockefeller Park Preserve Van Houten's Landing Historic District (!308 Park Rockefeller Park Preserve Union Church of Pocantico Hills State Park Hopper, Edward, Birthplace and Boyhood Home Philipse Manor Railroad Station Untouched Wilderness Dutch Reformed Church Rockefeller, John D., Estate Historic Site Tappan Zee Playhouse Philipsburg Manor St. Paul's United Methodist Church US Post Office--Nyack Scenic Area Ross-Hand Mansion McCullers, Carson, House Tarrytown Lighthouse (!309 Harden, Edward, Mansion Patriot's Park Foster Memorial A.M.E. Zion Church Irving, Washington, High School Music Hall North Grove Street Historic District DATA SOURCES: NYS DOT, ESRI, NOAA, TDI, TRC, NEW YORK STATE DEPARTMENT OF Christ Episcopal Church Blauvelt Wayside Chapel (Former) First Baptist Church and Rectory ENVIRONMENTAL CONSERVATION (NYDEC), NEW YORK STATE OFFICE OF PARKS RECREATION AND HISTORICAL PRESERVATION (OPRHP) Old Croton Aqueduct Old Croton Aqueduct NOTES: (!310 1. -

Delano Family Papers 1568

DELANO FAMILY PAPERS 1568 - 1919 Accession Numbers: 67-20, 79-5 The majority of these papers from "Steen Valetje", the Delano house at Barrytown, New York, were received at the Library from Warren Delano on April 21 and May 8, 1967. A small accretion to the papers was received from Mr. Delano on May 22, 1978. Literary property rights have been donated to the United States Government. Quantity: 22.1inear feet (approximately 55,000 pages) Restrictions: None Related Material: Additional Delano family material, given to the Library by President Roosevelt and other donors, has been filed with the Roosevelt Family Papers. The papers of Frederic Adrian Delano also contain family material dating from the 1830's. Correspondence from various Delano family members may also be found in the papers of Franklin D. and Eleanor Roosevelt. <,''- BIOGRAPHICAL SKETCH Many members of the Delano family in the United States, descended from Philippe de la Noye who arrived in Plymouth, Massachusetts in 1621, were involved in the New England sea trade. Captain Warren Delano (1779-1866), Franklin Delano Roosevelt's great-grandfather, was a sea captain and ship owner who sailed from Fairhaven, Massachusetts. He and his first wife, Deborah Perry Church (1783-1827), had the following children: Warren II 1809-1898 Frederick A. 1811-1857 Franklin Hughes 1813-1893 Louisa Church 1816-1846 Edward 1818-1881 Deborah Perry 1820-1846 Sarah Alvey 1822-1880 Susan Maria 1825-1841 Warren Delano II, President Roosevelt's grandfather, born July 13, 1809 in Fairhaven, also embarked upon a maritime career. In 1833, he sailed to China as supercargo on board the Commerce bound for Canton where he became associated with the shipping firm, Russell Sturgis and Company. -

3 Flushing Meadows Corona Park Strategic Framework Plan

Possible reconfiguration of the Meadow Lake edge with new topographic variation Flushing Meadows Corona Park Strategic Framework Plan 36 Quennell Rothschild & Partners | Smith-Miller + Hawkinson Architects Vision & Goals The river and the lakes organize the space of the Park. Our view of the Park as an ecology of activity calls for a large-scale reorganization of program. As the first phase in the installation of corridors of activity we propose to daylight the Flushing River and to reconfigure the lakes to create a continuous ribbon of water back to Flushing Bay. RECONFIGURE & RESTORE THE LAKES Flushing Meadows Corona Park is defined by water. Today, the Park meets Flushing Bay at its extreme northern channel without significantly impacting the ecological characteristics of Willow and Meadow Lakes and their end. At its southern end, the Park is dominated by the two large lakes, Willow Lake and Meadow Lake, created for shorelines. In fact, additional dredged material would be valuable resource for the reconfiguration of the lakes’ the 1939 World’s Fair. shoreline. This proposal would, of course, require construction of a larger bridge at Jewel Avenue and a redesign of the Park road system. The hydrology of FMCP was shaped by humans. The site prior to human interference was a tidal wetland. Between 1906 and 1934, the site was filled with ash and garbage. Historic maps prior to the ‘39 Fair show the Flushing To realize the lakes’ ecological value and their potential as a recreation resource with more usable shoreline and Creek meandering along widely varying routes through what later became the Park. -

New York City Comprehensive Waterfront Plan

NEW YORK CITY CoMPREHENSWE WATERFRONT PLAN Reclaiming the City's Edge For Public Discussion Summer 1992 DAVID N. DINKINS, Mayor City of New lVrk RICHARD L. SCHAFFER, Director Department of City Planning NYC DCP 92-27 NEW YORK CITY COMPREHENSIVE WATERFRONT PLAN CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMA RY 1 INTRODUCTION: SETTING THE COURSE 1 2 PLANNING FRA MEWORK 5 HISTORICAL CONTEXT 5 LEGAL CONTEXT 7 REGULATORY CONTEXT 10 3 THE NATURAL WATERFRONT 17 WATERFRONT RESOURCES AND THEIR SIGNIFICANCE 17 Wetlands 18 Significant Coastal Habitats 21 Beaches and Coastal Erosion Areas 22 Water Quality 26 THE PLAN FOR THE NATURAL WATERFRONT 33 Citywide Strategy 33 Special Natural Waterfront Areas 35 4 THE PUBLIC WATERFRONT 51 THE EXISTING PUBLIC WATERFRONT 52 THE ACCESSIBLE WATERFRONT: ISSUES AND OPPORTUNITIES 63 THE PLAN FOR THE PUBLIC WATERFRONT 70 Regulatory Strategy 70 Public Access Opportunities 71 5 THE WORKING WATERFRONT 83 HISTORY 83 THE WORKING WATERFRONT TODAY 85 WORKING WATERFRONT ISSUES 101 THE PLAN FOR THE WORKING WATERFRONT 106 Designation Significant Maritime and Industrial Areas 107 JFK and LaGuardia Airport Areas 114 Citywide Strategy fo r the Wo rking Waterfront 115 6 THE REDEVELOPING WATER FRONT 119 THE REDEVELOPING WATERFRONT TODAY 119 THE IMPORTANCE OF REDEVELOPMENT 122 WATERFRONT DEVELOPMENT ISSUES 125 REDEVELOPMENT CRITERIA 127 THE PLAN FOR THE REDEVELOPING WATERFRONT 128 7 WATER FRONT ZONING PROPOSAL 145 WATERFRONT AREA 146 ZONING LOTS 147 CALCULATING FLOOR AREA ON WATERFRONTAGE loTS 148 DEFINITION OF WATER DEPENDENT & WATERFRONT ENHANCING USES -

Weymouth Centered on Literature and Hunting That Continued up to James Boyd’S Death in 1944

Cultural Landscape Report for Weymouth Southern Pines, NC Davyd Foard Hood Landscape Historian & Glenn Thomas Stach Preservation Landscape Architect August 2011 Cultural Landscape Report for Weymouth Southern Pines, NC August 2011 Client: Town of Southern Pines This study was funded in part from the Historic Preservation Fund grant from the U.S. National Park Service through the North Carolina State Historic Preservation Office, with additional funding and support by the Southern Pines Garden Club Preparers: Davyd Foard Hood, Landscape Historian Glenn Thomas Stach, Preservation Landscape Architect Table of Contents List of Figures & Plans Introduction…………………………………………………………………….…….….…….viii Chapter I: History Narrative & Supporting Imagery………………………….….……I-1 thru 61 Chapter II: Existing Conditions & Supporting Imagery ………..…………....………II-1 thru 23 Chapter III: Analysis & Evaluation with Supporting Imagery……………………….III1 thru 20 Appendix A: Period, Existing, and Analysis Plans and Diagrams Appendix B: Boyd Family Genealogical Table Appendix C: Floor Plans Appendix D. Street Map of Southern Pines Weymouth Cultural Landscape Report List of Figures Chapter I I/1 View of Weymouth, looking southwest along the brick lined path in the lower terrace, showing plantings along the path by students in the Sandhills horticultural program launched in 1968, the cold frame, and dense shrub plantings in the lower terrace, the tall Japanese privet hedge separating the upper and lower terraces, and the manner by which Alfred B. Yeomans closed the axial view with the corner of the loggia in his ca. 1932 addition, ca. 1970. Weymouth Archives. I/2 Photograph of James Boyd, seated, ca. 1890‐1900, Weymouth Archives. I/3 Hand‐colored postal view, “Vermont Avenue, Southern Pines, N.C.”, by E. -

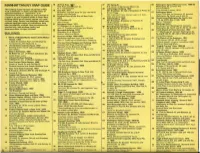

Manhattan N.V. Map Guide 18

18 38 Park Row. 113 37 101 Spring St. 56 Washington Square Memorial Arch. 1889·92 MANHATTAN N.V. MAP GUIDE Park Row and B kman St. N. E. corner of Spring and Mercer Sts. Washington Sq. at Fifth A ve. N. Y. Starkweather Stanford White The buildings listed represent ali periods of Nim 38 Little Singer Building. 1907 19 City Hall. 1811 561 Broadway. W side of Broadway at Prince St. First erected in wood, 1876. York architecture. In many casesthe notion of Broadway and Park Row (in City Hall Perk} 57 Washington Mews significant building or "monument" is an Ernest Flagg Mangin and McComb From Fifth Ave. to University PIobetween unfortunate format to adhere to, and a portion of Not a cast iron front. Cur.tain wall is of steel, 20 Criminal Court of the City of New York. Washington Sq. North and E. 8th St. a street or an area of severatblocks is listed. Many glass,and terra cotta. 1872 39 Cable Building. 1894 58 Housesalong Washington Sq. North, Nos. 'buildings which are of historic interest on/y have '52 Chambers St. 1-13. ea. )831. Nos. 21-26.1830 not been listed. Certain new buildings, which have 621 Broadway. Broadway at Houston Sto John Kellum (N.W. corner], Martin Thompson replaced significant works of architecture, have 59 Macdougal Alley been purposefully omitted. Also commissions for 21 Surrogates Court. 1911 McKim, Mead and White 31 Chembers St. at Centre St. Cu/-de-sac from Macdouga/ St. between interiorsonly, such as shops, banks, and 40 Bayard-Condict Building. -

Long Island Sound and East River NOAA Chart 12366

BookletChart™ Long Island Sound and East River NOAA Chart 12366 A reduced-scale NOAA nautical chart for small boaters When possible, use the full-size NOAA chart for navigation. Published by the shore are several villages. A 5 mph speed limit is enforced in the harbor. Glen Cove Creek, 0.6 mile southward of the breakwater, has a dredged National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration channel from Mosquito Cove to the head. In 1994, the controlling depth National Ocean Service was 2½ feet in the right half of the channel with shoaling to less than a Office of Coast Survey foot in the left half for about 0.6 mile above the entrance. The remainder of the project is not being maintained. The entrance is www.NauticalCharts.NOAA.gov buoyed. 888-990-NOAA Manhasset Bay, between Barker Point and Hewlett Point, affords excellent shelter for vessels of about 12 feet or less draft, and is much What are Nautical Charts? frequented by yachts in the summer. The depths in the outer part of the bay range from 12 to 17 feet, and 7 to 12 feet in the inner part inside Nautical charts are a fundamental tool of marine navigation. They show Plum Point. The extreme south end of the bay is shallow with extensive water depths, obstructions, buoys, other aids to navigation, and much mudflats. Depths of about 6 to 2 feet can be taken through a natural more. The information is shown in a way that promotes safe and channel almost to the head of the bay. A 5 mph speed limit is enforced. -

Landmarks Preservation Commission June 22, 2010, Designation List 430 LP-2388

Landmarks Preservation Commission June 22, 2010, Designation List 430 LP-2388 HAFFEN BUILDING, 2804-2808 Third Avenue (aka 507 Willis Avenue), the Bronx Built 1901-02; Michael J. Garvin, architect Landmark Site: Borough of the Bronx Tax Map Block 2307, Lot 59 On December 15, 2009, the Landmarks Preservation Commission held a public hearing on the proposed designation as a Landmark of the Haffen Building and the proposed designation of the related Landmark Site (Item No. 3). The hearing had been duly advertised in accordance with the provisions of law. Three people spoke in favor of designation, including representatives of the Historic Districts Council and the New York Landmarks Conservancy. Summary The Haffen Building is a seven-story Beaux-Arts style office building designed by architect Michael J. Garvin and erected in 1901 to 1902 by brewery owner Mathias Haffen. The building is located in the western Bronx neighborhood of Melrose, an area predominantly populated by German- Americans during the 19th and early 20th centuries. The Haffen Building was part of the rapid development of the “the Hub,” the commercial center of Melrose, which centered on the intersection of East 149th Street, Melrose, Willis and Third Avenues. By the turn of the 20th century, the Haffen family was one of the main families of the Bronx, having made essential contributions to the physical and social infrastructure of the Bronx including surveying and laying out of parks and the streets, developing real estate, and organizing of a number of civic, social, and financial institutions. Mathias Haffen was active in real estate development in Melrose and, in 1901, chose a prominent, through- block site between Third and Willis Avenues in the Hub to erect a first- class office building for banking and professional tenants. -

Tomorrow's World

Tomorrow’s World: The New York World’s Fairs and Flushing Meadows Corona Park The Arsenal Gallery June 26 – August 27, 2014 the “Versailles of America.” Within one year Tomorrow’s World: 10,000 trees were planted, the Grand Central Parkway connection to the Triborough Bridge The New York was completed and the Bronx-Whitestone Bridge well underway.Michael Rapuano’s World’s Fairs and landscape design created radiating pathways to the north influenced by St. Peter’s piazza in the Flushing Meadows Vatican, and also included naturalized areas Corona Park and recreational fields to the south and west. The Arsenal Gallery The fair was divided into seven great zones from Amusement to Transportation, and 60 countries June 26 – August 27, 2014 and 33 states or territories paraded their wares. Though the Fair planners aimed at high culture, Organized by Jonathan Kuhn and Jennifer Lantzas they left plenty of room for honky-tonk delights, noting that “A is for amusement; and in the interests of many of the millions of Fair visitors, This year marks the 50th and 75th anniversaries amusement comes first.” of the New York World’s Fairs of 1939-40 and 1964-65, cultural milestones that celebrated our If the New York World’s Fair of 1939-40 belonged civilization’s advancement, and whose visions of to New Dealers, then the Fair in 1964-65 was for the future are now remembered with nostalgia. the baby boomers. Five months before the Fair The Fairs were also a mechanism for transform- opened, President Kennedy, who had said, “I ing a vast industrial dump atop a wetland into hope to be with you at the ribbon cutting,” was the city’s fourth largest urban park.