Pnabr133.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Regional Project/Programme Proposal

REGIONAL PROJECT/PROGRAMME PROPOSAL PART I: PROJECT/PROGRAMME INFORMATION Title of Project/Programme: Improved Resilience of Coastal Communities in Côte d’Ivoire and Ghana. Countries: Côte d’Ivoire and Ghana. Thematic Focal Area: Disaster risk reduction and early warning systems Type of Implementing Entity: MIE Implementing Entity United Nations Human Settlements Programme Executing Entities: Ghana: LUSPA; NGO Côte d’Ivoire: Ministry of the Environment and Sustainable Development, Ministry of Planning and Development; NGOs Amount of Financing Requested: US$ 13,951,159 PROJECT BACKGROUND AND CONTEXT I. Problem statement Coastal cities and communities in West Africa are facing the combined challenges of rapid urbanisation and climate change, especially sea level rise and related increased risks of erosion, inundation and floods. For cities and communities in West Africa not to be flooded or submerged, and critically exposed to rising seas and storm surges in the next decade(s), they urgently need to increase the protection of their coastline and infrastructure, adapt to create alternative livelihoods in the inland and promote a climate change resilient urban development path. This can be done by using a combination of climate change sensitive spatial planning strategies and innovative and ecosystem-based solutions to protect land, people and assets, by implementing nature-based solutions and ‘living shorelines,’ which redirect the forces of nature rather than oppose them. The Governments of Ghana and Côte d’Ivoire have requested UN-Habitat to support coastal (and riverine / delta) cities and communities to better adapt to climate change. This project proposal aims at responding to this request by addressing the main challenges in these coastal zones: coastal erosion, coastal inundation / flooding and livelihoods’ resilience. -

Côte D'ivoire

CÔTE D’IVOIRE COI Compilation August 2017 United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees Regional Representation for West Africa - RSD Unit UNHCR Côte d’Ivoire UNHCR Regional Representation for West Africa - RSD Unit UNHCR Côte d’Ivoire Côte d’Ivoire COI Compilation August 2017 This report collates country of origin information (COI) on Côte d’Ivoire up to 15 August 2017 on issues of relevance in refugee status determination for Ivorian nationals. The report is based on publicly available information, studies and commentaries. It is illustrative, but is neither exhaustive of information available in the public domain nor intended to be a general report on human-rights conditions. The report is not conclusive as to the merits of any individual refugee claim. All sources are cited and fully referenced. Users should refer to the full text of documents cited and assess the credibility, relevance and timeliness of source material with reference to the specific research concerns arising from individual applications. UNHCR Regional Representation for West Africa Immeuble FAALO Almadies, Route du King Fahd Palace Dakar, Senegal - BP 3125 Phone: +221 33 867 62 07 Kora.unhcr.org - www.unhcr.org Table of Contents List of Abbreviations .............................................................................................................. 4 1 General Information ....................................................................................................... 5 1.1 Historical background ............................................................................................ -

DRENET KATIOLA : Statistiques Scolaires De Poche 2019-2020: Région Du Hambol 1 AVANT-PROPOS

DRENET KATIOLA : Statistiques scolaires de poche 2019-2020: Région du Hambol 1 AVANT-PROPOS AVANT- PROPOS La publication des données statistiques contribue au pilotage du système éducatif. Elle participe à la planification des besoins recensés au niveau du Ministère de l’Education Nationale, de l’Enseignement Technique et de la Formation Professionnelle sur l’ensemble du territoire National. A cet effet, la Direction des Stratégies, de la Planification et des Statistiques (DSPS) publie, tous les ans, les statistiques scolaires par degré d’enseignement (Préscolaire, Primaire, Secondaire général et technique). Compte tenu de l’importance des données statistiques scolaires, la DSPS, après la publication du document « Statistiques Scolaires de Poche » publié au niveau national, a jugé nécessaire de proposer aux usagers, le même type de document au niveau de chaque région administrative. Ce document comportant les informations sur l’éducation est le miroir expressif de la réalité du système éducatif régional. La possibilité pour tous les acteurs et partenaires de l’école ivoirienne de pouvoir disposer, en tout temps et en tout lieu, des chiffres et indicateurs présentant une vision d’ensemble du système éducatif d’une région donnée, constitue en soi une valeur ajoutée. La DSPS est résolue à poursuivre la production des statistiques scolaires de poche nationales et régionales de façon régulière pour aider les acteurs et partenaires du système éducatif dans les prises de décisions adéquates et surtout dans ce contexte de crise sanitaire liée à la COVID-19. DRENET KATIOLA : Statistiques scolaires de poche 2019-2020: Région du Hambol 2 PRESENTATION La Direction des Stratégies, de la Planification et des Statistiques (DSPS) est heureuse de mettre à la disposition de la communauté éducative les statistiques scolaires de poche 2019- 2020 de la Région. -

Spatio-Temporal Analysis of the Impact of Rainfall Dynamics on the Water Resources of the N'zi Watershed in Côte D'ivoire

Spatio-temporal analysis of the impact of rainfall dynamics on the water resources of the N'zi watershed in Côte d'Ivoire ABSTRACT This study aims to analyze impacts of rainfall dynamic on the water resources (surface water and groundwater) of N'zi watershed in Côte d'Ivoire. It justifies use of monthly average climatological data (rainfall, temperature) and hydrometric data of the watershed. The methodology is to interpolate by kriging rainfall, to highlight relationship between the spatial variability of rainfall and the surface water flow, and to evaluate groundwater recharge of fractured aquifers in the watershed. At the end of the study, it appears that the ten-year average rainfall of the N'zi watershed has decreased significantly. From 1233 mm during the decade 1951-1960, it lowered to 1074 mm during the decade 1991-2000. During the decades 1961-1970, 1971-1980 and 1981-1990, average rainfall is estimated at 1213 mm, 1068 mm and 1050 mm, respectively. From a spatial point of view, decrease in rainfall intensity was strongly felt in the central and northern localities, as in those located in the south of the watershed. Evolution of stream flow and rainfall is similar in the upper and middle N'zi, with maximum flow period in september corresponding mainly to the period of high rainfall. However, two peaks of different amplitude and a slight shift are observed between the peaks of rain and those of flow mainly in low N'zi. Water quantity streamed in the N’zi watershed during the period of 1972 to 2000 is of 40.7 mm. -

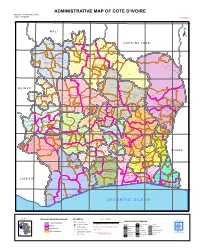

ADMINISTRATIVE MAP of COTE D'ivoire Map Nº: 01-000-June-2005 COTE D'ivoire 2Nd Edition

ADMINISTRATIVE MAP OF COTE D'IVOIRE Map Nº: 01-000-June-2005 COTE D'IVOIRE 2nd Edition 8°0'0"W 7°0'0"W 6°0'0"W 5°0'0"W 4°0'0"W 3°0'0"W 11°0'0"N 11°0'0"N M A L I Papara Débété ! !. Zanasso ! Diamankani ! TENGRELA [! ± San Koronani Kimbirila-Nord ! Toumoukoro Kanakono ! ! ! ! ! !. Ouelli Lomara Ouamélhoro Bolona ! ! Mahandiana-Sokourani Tienko ! ! B U R K I N A F A S O !. Kouban Bougou ! Blésségué ! Sokoro ! Niéllé Tahara Tiogo !. ! ! Katogo Mahalé ! ! ! Solognougo Ouara Diawala Tienny ! Tiorotiérié ! ! !. Kaouara Sananférédougou ! ! Sanhala Sandrégué Nambingué Goulia ! ! ! 10°0'0"N Tindara Minigan !. ! Kaloa !. ! M'Bengué N'dénou !. ! Ouangolodougou 10°0'0"N !. ! Tounvré Baya Fengolo ! ! Poungbé !. Kouto ! Samantiguila Kaniasso Monogo Nakélé ! ! Mamougoula ! !. !. ! Manadoun Kouroumba !.Gbon !.Kasséré Katiali ! ! ! !. Banankoro ! Landiougou Pitiengomon Doropo Dabadougou-Mafélé !. Kolia ! Tougbo Gogo ! Kimbirila Sud Nambonkaha ! ! ! ! Dembasso ! Tiasso DENGUELE REGION ! Samango ! SAVANES REGION ! ! Danoa Ngoloblasso Fononvogo ! Siansoba Taoura ! SODEFEL Varalé ! Nganon ! ! ! Madiani Niofouin Niofouin Gbéléban !. !. Village A Nyamoin !. Dabadougou Sinémentiali ! FERKESSEDOUGOU Téhini ! ! Koni ! Lafokpokaha !. Angai Tiémé ! ! [! Ouango-Fitini ! Lataha !. Village B ! !. Bodonon ! ! Seydougou ODIENNE BOUNDIALI Ponondougou Nangakaha ! ! Sokoro 1 Kokoun [! ! ! M'bengué-Bougou !. ! Séguétiélé ! Nangoukaha Balékaha /" Siempurgo ! ! Village C !. ! ! Koumbala Lingoho ! Bouko Koumbolokoro Nazinékaha Kounzié ! ! KORHOGO Nongotiénékaha Togoniéré ! Sirana -

GAFSP Proposal NAIP 2 Programs

Global Agriculture and Food Security Program (GAFSP) Public Sector Window 2019 Call for Proposals Country: Republic of Cote d'Ivoire Project Name: Strengthening smallholders and women’s livelihoods and resilience in the N'ZI region 0 Abstract Two decades of political instability and armed conflict in Côte d’Ivoire resulted in more than 3,000 deaths and hundreds of thousands of displaced persons, and profoundly changed the country. The post-election crisis of 2010-11 exacerbated the social fragility that previously existed, leading to the deployment of the United Nations Operations in Côte d’Ivoire for 13 years, from 2004 to 2017. While the country experienced rapid economic recovery and sustained economic growth leading to the withdrawal of the UN mission in 2017, economic success must not mask the fragility of Côte d'Ivoire. The country continues to experience community conflicts, armed mutinies, and rising political tensions ahead of presidential elections scheduled for 2020. The root causes of previous conflicts have not been addressed and conflicts. In addition, instability in the region with terrorist threats in the neighbouring countries continue to put the country at risks of conflicts. The country ranked 170th out of 189 countries in the 2018 Human Development Index Report. More than 10 million people, or about 46.3% (55.4% in rural areas) of the population live below the poverty line. Hunger and malnutrition are on the rise as the result of conflicts, climate change and lack of investment in the agricultural sector. The effects of this crisis have significantly affected the livelihoods of the population, constraining small scale farmers to produce enough food. -

See Full Prospectus

G20 COMPACT WITHAFRICA CÔTE D’IVOIRE Investment Opportunities G20 Compact with Africa 8°W To 7°W 6°W 5°W 4°W 3°W Bamako To MALI Sikasso CÔTE D'IVOIRE COUNTRY CONTEXT Tengrel BURKINA To Bobo Dioulasso FASO To Kampti Minignan Folon CITIES AND TOWNS 10°N é 10°N Bagoué o g DISTRICT CAPITALS a SAVANES B DENGUÉLÉ To REGION CAPITALS Batie Odienné Boundiali Ferkessedougou NATIONAL CAPITAL Korhogo K RIVERS Kabadougou o —growth m Macroeconomic stability B Poro Tchologo Bouna To o o u é MAIN ROADS Beyla To c Bounkani Bole n RAILROADS a 9°N l 9°N averaging 9% over past five years, low B a m DISTRICT BOUNDARIES a d n ZANZAN S a AUTONOMOUS DISTRICT and stable inflation, contained fiscal a B N GUINEA s Hambol s WOROBA BOUNDARIES z a i n Worodougou d M r a Dabakala Bafing a Bere REGION BOUNDARIES r deficit; sustainable debt Touba a o u VALLEE DU BANDAMA é INTERNATIONAL BOUNDARIES Séguéla Mankono Katiola Bondoukou 8°N 8°N Gontougo To To Tanda Wenchi Nzerekore Biankouma Béoumi Bouaké Tonkpi Lac de Gbêke Business friendly investment Mont Nimba Haut-Sassandra Kossou Sakassou M'Bahiakro (1,752 m) Man Vavoua Zuenoula Iffou MONTAGNES To Danane SASSANDRA- Sunyani Guemon Tiebissou Belier Agnibilékrou climate—sustained progress over the MARAHOUE Bocanda LACS Daoukro Bangolo Bouaflé 7°N 7°N Daloa YAMOUSSOUKRO Marahoue last four years as measured by Doing Duekoue o Abengourou b GHANA o YAMOUSSOUKRO Dimbokro L Sinfra Guiglo Bongouanou Indenie- Toulepleu Toumodi N'Zi Djuablin Business, Global Competitiveness, Oumé Cavally Issia Belier To Gôh CÔTE D'IVOIRE Monrovia -

Emergences Endémiques De Fièvre Jaune Dans La Région

LABORATOIRE D'ENTOMOLOGIE MEDICALE O.R.S.T.O.M. DE L'INSTITUT PASTEUR DE COTE D'IVOIRE O1 BP V-51 Abid.jan O1 O1 BP 490 Abidjan O1 EPERGENCES ENDEMIQUES DE FIEVRE JAUNE DANS LA REGION DE NIAKARAMANDOUGOU REPUBLIQUE DE COTE D'IVOIRE. ENQUETE ENTOMO - EPIDEMIOLOGIQUE -. Roger CORDELLIER Bernard BOUCHITE Dr. es-Sciences Technicien supérieur Entomologiste médical ORSTOM d''Entomologie médicale ORSTOM . c I- 1 1. INTRODUCTION . Le décès le 28 novembre 1982 à l'hôpital de Bouaké, après son trans- fert depuis l'hôpital de Niakaramandougou, d'un Instituteur de 24 ans, a pu être rapporté 2 la fièvre jaune par le Dr. M. LHUILLIER (IgM sur un sé- rumpparvenu seulement le 10 décembre à l'Institut Pasteur). Une enquête conjointe IPCI/ORSTOM a été aussitôt décidée. En ce qui concernc le Laboratoire d'Entomologie médicale, elle s'est inscrite dans le cadre de la mission mensuelle effectuée à Dabakala (Surveillance de la fièvre jaune, de la dengue, et:autres arboviroses humaines dans la zone des sava- nes semi-humides), et ses différentes phases réalisées le 14, le 17 et le 19 décembre, B partir de la station de Dabakala, avec le personnel perma- nent du Laboratoire, et le personnel embauché localement sur la station. Les renseignements obtenus, et les observations faites sur place, 1. B l'hôpital de Niakaramandougou, dès le 14 décembre, nous ont conduit à centrer les prospections sur le village de OUREGUEKAHA (nouveau village), situé à environ 25 Km au sud de Niakaramandougou, et sur ARIKOKAHA, village de l'instituteur décédé, 2' 18 Km au nord. -

République De Cote D'ivoire

R é p u b l i q u e d e C o t e d ' I v o i r e REPUBLIQUE DE COTE D'IVOIRE C a r t e A d m i n i s t r a t i v e Carte N° ADM0001 AFRIQUE OCHA-CI 8°0'0"W 7°0'0"W 6°0'0"W 5°0'0"W 4°0'0"W 3°0'0"W Débété Papara MALI (! Zanasso Diamankani TENGRELA ! BURKINA FASO San Toumoukoro Koronani Kanakono Ouelli (! Kimbirila-Nord Lomara Ouamélhoro Bolona Mahandiana-Sokourani Tienko (! Bougou Sokoro Blésségu é Niéllé (! Tiogo Tahara Katogo Solo gnougo Mahalé Diawala Ouara (! Tiorotiérié Kaouara Tienn y Sandrégué Sanan férédougou Sanhala Nambingué Goulia N ! Tindara N " ( Kalo a " 0 0 ' M'Bengué ' Minigan ! 0 ( 0 ° (! ° 0 N'd énou 0 1 Ouangolodougou 1 SAVANES (! Fengolo Tounvré Baya Kouto Poungb é (! Nakélé Gbon Kasséré SamantiguilaKaniasso Mo nogo (! (! Mamo ugoula (! (! Banankoro Katiali Doropo Manadoun Kouroumba (! Landiougou Kolia (! Pitiengomon Tougbo Gogo Nambonkaha Dabadougou-Mafélé Tiasso Kimbirila Sud Dembasso Ngoloblasso Nganon Danoa Samango Fononvogo Varalé DENGUELE Taoura SODEFEL Siansoba Niofouin Madiani (! Téhini Nyamoin (! (! Koni Sinémentiali FERKESSEDOUGOU Angai Gbéléban Dabadougou (! ! Lafokpokaha Ouango-Fitini (! Bodonon Lataha Nangakaha Tiémé Villag e BSokoro 1 (! BOUNDIALI Ponond ougou Siemp urgo Koumbala ! M'b engué-Bougou (! Seydougou ODIENNE Kokoun Séguétiélé Balékaha (! Villag e C ! Nangou kaha Togoniéré Bouko Kounzié Lingoho Koumbolokoro KORHOGO Nongotiénékaha Koulokaha Pign on ! Nazinékaha Sikolo Diogo Sirana Ouazomon Noguirdo uo Panzaran i Foro Dokaha Pouan Loyérikaha Karakoro Kagbolodougou Odia Dasso ungboho (! Séguélon Tioroniaradougou -

Annuaire Statistique D'état Civil 2018

1 2 3 REPUBLIQUE DE CÔTE D’IVOIRE Union – Discipline – Travail MINISTERE DE L'INTERIEUR ET DE LA SECURITE ----------------------------------- DIRECTION DES ETUDES, DE LA PROGRAMMATION ET DU SUIVI-EVALUATION ANNUAIRE STATISTIQUE D'ETAT CIVIL 2018 Les personnes ci-après ont contribué à l’élaboration de cet annuaire : MIS/DEPSE - Dr Amoncou Fidel YAPI - Ange-Lydie GNAHORE Epse GANNON - Taneaucoa Modeste Eloge KOYE MIS/DGAT - Roland César GOGO MIS/DGDDL - Botty Maxime GOGONE-BI - Simon Pierre ASSAMOI MJDH/DECA - Rigobert ZEBA - Kouakou Charles-Elie YAO MIS/ONECI - Amone KOUDOUGNON Epse DJAGOURI MSHP/DIIS - Daouda KONE MSHP/DCPEV - Moro Janus AHI SOUS-PREFECTURE DE - Affoué Jeannette KOUAKOU Epse GUEI JACQUEVILLE SOUS-PREFECTURE DE KREGBE - Hermann TANO MPD/INS - Massoma BAKAYOKO - N'Guethas Sylvie Koutoua GNANZOU - Brahima TOURE MPD/ONP - Bouangama Didier SEMON INTELLIGENCE MULTIMEDIA - Gnekpié Florent YAO - Cicacy Kwam Belhom N’GORAN UNICEF - Mokie Hyacinthe SIGUI 1 2 PREFACE Dans sa marche vers le développement, la Côte d’Ivoire s’est dotée d’un Plan National de Développement (PND) 2016-2020 dont l’une des actions prioritaires demeure la réforme du système de l’état civil. A ce titre, le Gouvernement ivoirien a pris deux (02) lois portant sur l’état civil : la loi n°2018-862 du 19 novembre 2018 relative à l’état civil et la loi n°2018-863 du 19 novembre 2018 instituant une procédure spéciale de déclaration de naissance, de rétablissement d’identité et de transcription d’acte de naissance. La Côte d’Ivoire attache du prix à l’enregistrement des faits d’état civil pour la promotion des droits des individus, la bonne gouvernance et la planification du développement. -

Stakeholder Engagement Plan Extension of Power Plant – CIPREL 5 Abidjan, Ivory Coast ATINKOU

Stakeholder Engagement Plan Extension of Power Plant – CIPREL 5 Abidjan, Ivory Coast ATINKOU - ERANOVE Version 1 - January 2019 The Business of Sustainability STAKEHOLDER ENGAGEMENT PLAN Project CIPREL 5, Power Station Final version For ERM France SAS Approved by: Juliette Ambroselli Signature: Date: January 2019 This document has been prepared by ERM France SAS with all due skill, care and reasonable diligence with respect to the terms of the contract with the customer, which incorporates the Terms of Service Delivery and taking into account the resources allocated to this work agreed with the Client. We disclaim any vis-à-vis the Client for any Another topic that is not part of the specification accepted by the Customer under the contract. This document is confidential and intended only for the client. Therefore, we assume no liability of any nature whatsoever vis-à- vis third parties to whom all or part of the document was communicated. Any third party wishing to rely on this document does so at its own risk. TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 INTRODUCTION AND DEVELOPMENT CONTEXT 6 1.1 BACKGROUND DOCUMENT 6 1.1.1 The Developer Project 7 1.1.2 The ERANOVE Project Phase 58 1.2 PRINCIPLES OF ENGAGEMENT PARTY STAKEHOLDERS 8 1.3 OVERVIEW PRAFT 9 1.4 STRUCTURE OF THE SEP 10 2 NATIONAL AND INTERNATIONAL STANDARDS FOR REQUIREMENTS COMMITMENT PARTIES STAKEHOLDERS 11 2.1 NATIONAL REQUIREMENT FOR CONSULTING THE PARTIES CONCERNED 11 2.1.1 The Code of the environment 11 2.1.2 Approval Process ESIA 11 2.2 PERFORMANCE STANDARDS SOCIETAL 12 2.3 SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT -

186 Structure De La Végétation Des Forêts De Dimbokro L'une Des

Afrique SCIENCE 15(2) (2019) 186 - 196 186 ISSN 1813-548X, http://www.afriquescience.net Structure de la végétation des forêts de Dimbokro l’une des régions les plus chaudes de la Côte d’Ivoire 1,3* 1,2 3 Rita Massa BIAGNE , François N’Guessan KOUAME et Edouard Kouakou N’GUESSAN 1 Centre d’Excellence Africain sur le Changement Climatique, la Biodiversité et l’Agriculture Durable, Bingerville, Côte d’Ivoire 2 Université Nangui Abrogoua, UFR Sciences de la Nature, 31 BP 165 Abidjan 31, Côte d’Ivoire 3 Université Félix Houphouët-Boigny, UFR Biosciences, Laboratoire de Botanique, 22 BP 582 Abidjan 22, Côte d’Ivoire _________________ * Correspondance, courriel : [email protected] Résumé La présente étude, menée au Centre-Est de la Côte d’Ivoire sur la végétation ligneuse, a pour objectif principal d’estimer la quantité de biomasse ligneuse, la densité et le potentiel de séquestration du carbone des forêts dans le Département de Dimbokro. Trois types de forêts constitués par les forêts galeries, les forêts classées et les forêts de plateaux ont été comparées à l’aide des données sur les diamètres à hauteur de poitrine (DHP) et les hauteurs totales des individus de DHP ≥ 10 cm. Les données ont été collectées dans 90 parcelles de 1000 m2 chacune dans l’ensemble des forêts, à raison de 30 parcelles dans chaque type de forêts. Les résultats montrent que la biomasse aérienne varie de 100,275 T / Ha, dans les forêts galeries, à 160,391 T / Ha, dans les forêts classées pendant que la densité varie de 323 tiges / Ha, dans les forêts de plateaux, à 517 tiges / Ha, dans les forêts classées.