"Lehrstücke" and the Nazi

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jonathan Berger, an Introduction to Nameless Love

For Immediate Release Contact: [email protected], 646-492- 4076 Jonathan Berger, An Introduction to Nameless Love In collaboration with Mady Schutzman, Emily Anderson, Tina Beebe, Julian Bittiner, Matthew Brannon, Barbara Fahs Charles, Brother Arnold Hadd, Erica Heilman, Esther Kaplan, Margaret Morton, Richard Ogust, Maria A. Prado, Robert Staples, Michael Stipe, Mark Utter, Michael Wiener, and Sara Workneh February 23 – April 5, 2020 Opening Sunday, February 23, noon–7pm From February 23 – April 5, 2020, PARTICIPANT INC is pleased to present Jonathan Berger, An Introduction to Nameless Love, co-commissioned and co-organized with the Carpenter Center for the Visual Arts at Harvard University. Taking the form of a large-scale sculptural installation that includes over 533,000 tin, nickel, and charcoal parts, Berger’s exhibition chronicles a series of remarkable relationships, creating a platform for complex stories about love to be told. The exhibition draws from Berger’s expansive practice, which comprises a spectrum of activity — brought together here for the first time — including experimental approaches to non-fiction, sculpture and installation, oral history and biography-based narratives, and exhibition-making practices. Inspired by a close friendship with fellow artist Ellen Cantor (1961-2013), An Introduction to Nameless Love charts a series of six extraordinary relationships, each built on a connection that lies outside the bounds of conventional romance. The exhibition is an examination of the profound intensity and depth of meaning most often associated with “true love,” but found instead through bonds based in work, friendship, religion, service, mentorship, community, and family — as well as between people and themselves, places, objects, and animals. -

Schulchronik Kalenborn

- 1 - Schulchronik Kalenborn transkribiert und kommentiert von Peter Leuschen Stand: 17. November 2016 - 2 - Vorbemerkung Im Archiv der Grundschule Gerolstein wird als "Schulchronik Kalenborn" ein Satz von Dokumenten geführt, der ursprünglich in der Schule Kalenborn verwahrt wurde und die Jahre von 1.5.1919 bis zum 1.8.1973 umfasst, zu welchem Datum die Schule aufgelöst wurde und die Unterlagen an die Rechtsnachfolgerin übergingen, nämlich die Grundschule Gerolstein. Deren Hausmeister, Herr Dahm, stellte die Originale dankenswerterweise zur Einsicht zur Verfügung. Als ich meinen erwachsenen Kindern die älteren Bände zeigte, gab es nur verständnisloses Kopfschütteln – die Sütterlinschrift1 ist größtenteils schon für meine Generation nicht mehr entzifferbar. Insofern hätte ein einfaches Einscannen der Hefte zwar deren visuellen Zugang vorerst gesichert, aber keinesfalls deren Rezipierbarkeit. Daher entschloss ich mich zu der zeitraubenden Prozedur, die Texte zu transkribieren und digital für das Internet zugänglich zu machen. Bei der Texterfassung wurde deutlich, dass die Fülle des Materials durch Orts-2, Personen-3 und Sachregister4 erschließbar gemacht werden sollte, woraus folgerte, dass die sechs Einzelteile zu einem Gesamtband zusammenzufassen sind, damit die von der Software zur Textverarbeitung bereitgestellte automatische Indexierung Seitenreferenzen über den Gesamttext erstellen kann. Andererseits sollte der Seitenlauf beibehalten werden, damit an jeder Stelle zitierbar ist, um welche Seite aus welchem der sechs Teile es sich handelt. -

Gender and Fairy Tales

Issue 2013 44 Gender and Fairy Tales Edited by Prof. Dr. Beate Neumeier ISSN 1613-1878 About Editor Prof. Dr. Beate Neumeier Gender forum is an online, peer reviewed academic University of Cologne journal dedicated to the discussion of gender issues. As English Department an electronic journal, gender forum offers a free-of- Albertus-Magnus-Platz charge platform for the discussion of gender-related D-50923 Köln/Cologne topics in the fields of literary and cultural production, Germany media and the arts as well as politics, the natural sciences, medicine, the law, religion and philosophy. Tel +49-(0)221-470 2284 Inaugurated by Prof. Dr. Beate Neumeier in 2002, the Fax +49-(0)221-470 6725 quarterly issues of the journal have focused on a email: [email protected] multitude of questions from different theoretical perspectives of feminist criticism, queer theory, and masculinity studies. gender forum also includes reviews Editorial Office and occasionally interviews, fictional pieces and poetry Laura-Marie Schnitzler, MA with a gender studies angle. Sarah Youssef, MA Christian Zeitz (General Assistant, Reviews) Opinions expressed in articles published in gender forum are those of individual authors and not necessarily Tel.: +49-(0)221-470 3030/3035 endorsed by the editors of gender forum. email: [email protected] Submissions Editorial Board Target articles should conform to current MLA Style (8th Prof. Dr. Mita Banerjee, edition) and should be between 5,000 and 8,000 words in Johannes Gutenberg University Mainz (Germany) length. Please make sure to number your paragraphs Prof. Dr. Nilufer E. Bharucha, and include a bio-blurb and an abstract of roughly 300 University of Mumbai (India) words. -

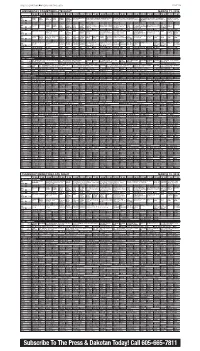

Subscribe to the Press & Dakotan Today!

PRESS & DAKOTAN n FRIDAY, MARCH 6, 2015 PAGE 9B WEDNESDAY PRIMETIME/LATE NIGHT MARCH 11, 2015 3:00 3:30 4:00 4:30 5:00 5:30 6:00 6:30 7:00 7:30 8:00 8:30 9:00 9:30 10:00 10:30 11:00 11:30 12:00 12:30 1:00 1:30 BROADCAST STATIONS Arthur Å Odd Wild Cyber- Martha Nightly PBS NewsHour (N) (In Suze Orman’s Financial Solutions for You 50 Years With Peter, Paul and Mary Perfor- John Sebastian Presents: Folk Rewind NOVA The tornado PBS (DVS) Squad Kratts Å chase Speaks Business Stereo) Å Finding financial solutions. (In Stereo) Å mances by Peter, Paul and Mary. (In Stereo) Å (My Music) Artists of the 1950s and ’60s. (In outbreak of 2011. (In KUSD ^ 8 ^ Report Stereo) Å Stereo) Å KTIV $ 4 $ Meredith Vieira Ellen DeGeneres News 4 News News 4 Ent Myst-Laura Law & Order: SVU Chicago PD News 4 Tonight Show Seth Meyers Daly News 4 Extra (N) Hot Bench Hot Bench Judge Judge KDLT NBC KDLT The Big The Mysteries of Law & Order: Special Chicago PD Two teen- KDLT The Tonight Show Late Night With Seth Last Call KDLT (Off Air) NBC (N) Å Å Judy Å Judy Å News Nightly News Bang Laura A star athlete is Victims Unit Å (DVS) age girls disappear. News Starring Jimmy Fallon Meyers (In Stereo) Å With Car- News Å KDLT % 5 % (N) Å News (N) (N) Å Theory killed. Å Å (DVS) (N) Å (In Stereo) Å son Daly KCAU ) 6 ) Dr. -

Stephen R. Grimm Curriculum Vitae Philosophy Department Office: 718-817-3282 Fordham University [email protected] Bronx, NY 10458 Stephenrgrimm.Com

Stephen R. Grimm Curriculum Vitae Philosophy Department Office: 718-817-3282 Fordham University [email protected] Bronx, NY 10458 stephenrgrimm.com Employment Fordham University: Professor (2016—), Associate Professor (2012—2016), Assistant Professor (2008—2012); Chair of Department (2017—) University of Montana: Assistant Professor (2006—2008) University of Notre Dame, Edward Sorin Postdoctoral Fellow (2005—2006) Education University of Notre Dame: Philosophy, Ph.D., 2005 University of Toronto, St. Michael's College: Theology, M.A., 1996 Williams College: B.A., 1993 Areas of Specialization Epistemology • Philosophy of Science (incl. Philosophy of Social Science) Areas of Competence Ethics • Philosophy of Religion • Wittgenstein Publications Books Varieties of Understanding: New Perspectives from Philosophy, Psychology, and Theology. Ed. Stephen R. Grimm. New York: Oxford University Press. (2019) Making Sense of the World: New Essays in the Philosophy of Understanding. Ed. Stephen R. Grimm. New York: Oxford University Press. (2018) 2 Explaining Understanding: New Essays in Epistemology and Philosophy of Science. Eds. Stephen R. Grimm, Christoph Baumberger, & Sabine Ammon. New York: Routledge. (2016) Series Editor for Oxford University Press line Guides to the Good Life (a new series of trade books on various figures and traditions, featuring the idea of “philosophy as a way of life”) Special Journal Issue Wisdom and Adversity. Special Issue of The Journal of Value Inquiry. Eds. Laura Blackie, Stephen R. Grimm, Eranda Jayawickreme. (2019) Articles “Transmitting Understanding and Know How." In What the Ancients Offer to Contemporary Epistemology. Eds. Stephen Hetherington and Nicholas Smith. New York: Routledge. (2020) "Does Adversity Make Us Wiser than Before? Addressing a Foundational Question Through Interdisciplinary Engagement." (with Laura Blackie and Eranda Jayawickreme) The Journal of Value Inquiry 53: 343-48. -

And When I Die and Other Prose

And When I Die and Other Prose A Thesis Presented for the Master of Arts Degree The University of Tennessee at Chattanooga Ralph Brandon Buckner III December 2010 Copyright © 2010 by Ralph Brandon Buckner III The Graduate School of the University of Tennessee at Chattanooga All rights reserved. ii Dedication: The chapter of the novel, the short stories, and the essays would not have been possible without: My family, for their love and for their neuroses. And especially to my little sister, Shipley, I miss her very much. iii Abstract This thesis consists of the first chapter of my novel, two short stories, and two nonfiction essays. These pieces explore the tensions of family, love, and sexual orientation. The most prominent theme that connects each work is the main character’s search for control in his life. In the introduction to this thesis, I critically analyze three novels that focus on characters trying to regain stability in their lives after the death of someone close to them, and then I have discussed how these novels shaped my thesis in terms of theme, mood, and conflict. iv Table of Contents Introduction 1 First Chapter of And When I Die 11 Windup 24 Almost Here 37 Shattered Machine 53 Blackout 64 Bibliography 75 v Introduction In the introduction to my thesis, I will focus on three novels that portray protagonists coping with the aftermath of a loved one’s death and the reconstruction of their lives. These themes resonate with my thesis as my protagonists search for a sense of control in their lives, either with dealing with death, love, or relationships. -

Kinsella Feb 13

MORPHEUS: A BILDUNGSROMAN A PARTIALLY BACK-ENGINEERED AND RECONSTRUCTED NOVEL MORPHEUS: A BILDUNGSROMAN A PARTIALLY BACK-ENGINEERED AND RECONSTRUCTED NOVEL JOHN KINSELLA B L A Z E V O X [ B O O K S ] Buffalo, New York Morpheus: a Bildungsroman by John Kinsella Copyright © 2013 Published by BlazeVOX [books] All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced without the publisher’s written permission, except for brief quotations in reviews. Printed in the United States of America Interior design and typesetting by Geoffrey Gatza First Edition ISBN: 978-1-60964-125-2 Library of Congress Control Number: 2012950114 BlazeVOX [books] 131 Euclid Ave Kenmore, NY 14217 [email protected] publisher of weird little books BlazeVOX [ books ] blazevox.org 21 20 19 18 17 16 15 14 13 12 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 B l a z e V O X trip, trip to a dream dragon hide your wings in a ghost tower sails crackling at ev’ry plate we break cracked by scattered needles from Syd Barrett’s “Octopus” Table of Contents Introduction: Forging the Unimaginable: The Paradoxes of Morpheus by Nicholas Birns ........................................................ 11 Author’s Preface to Morpheus: a Bildungsroman ...................................................... 19 Pre-Paradigm .................................................................................................. 27 from Metamorphosis Book XI (lines 592-676); Ovid ......................................... 31 Building, Night ...................................................................................................... -

Art and Political Ideology : the Bauhaus As Victim

/ART AND POLITICAL IDEOLOGY: THE BAUHAUS AS VICTIM by LACY WOODS DICK A., Randolph-Macon Woman's College, 1959 A MASTER'S THESIS submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree MASTER OF ARTS Department of History KANSAS STATE UNIVERSITY Manhattan, Kansas 1984 Approved by: Donald J. ftrozek A113D5 bSllSfl T4 vM4- c. 3~ TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Preface iii Chapter I Introduction 1 Chapter II The Bauhaus Experience: In Pursuit of the Aesthetic Chapter III The Bauhaus Image: Views of the Outsiders 48 Chapter IV Nazi Culture: Art and Ideology 92 Chapter V Conclusion 119 Endnotes 134 Selected Bibliography 150 -PREFACE- The Bauhaus, as a vital entity of the Weimar Republic and as a concept of modernity and the avant-garde, has been the object of an ongoing study for me during the months I have spent in the History Depart- ment at Kansas State University. My appreciation and grateful thanks go to the faculty members who patiently encouraged me in the historical process: to Dr. Marion Gray, who fostered my enthusiasm for things German; to Dr. George Kren, who closely followed my investigations of both intellectual thought and National Socialism; to Dr. LouAnn Culley who brought to life the nineteenth and twentieth century art world; and to Dr. Donald Mrozek who guided this historical pursuit and through- out demanded explicit definition and precise expression. I am also indebted to the Interlibrary Loan Department of the Farrell Library who tirelessly and cheerfully searched out and acquired many of the materials necessary for this study. Chapter I Introduction John Ruskin and William Morris, artist-philosophers of raid-nine- teenth century England, recognized and deplored the social isolation of art with artists living and working apart from society. -

Dialogues Between Media

Dialogues between Media The Many Languages of Comparative Literature / La littérature comparée: multiples langues, multiples langages / Die vielen Sprachen der Vergleichenden Literaturwissenschaft Collected Papers of the 21st Congress of the ICLA Edited by Achim Hölter Volume 5 Dialogues between Media Edited by Paul Ferstl ISBN 978-3-11-064153-0 e-ISBN (PDF) 978-3-11-064205-6 e-ISBN (EPUB) 978-3-11-064188-2 DOI https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110642056 This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial-No Derivatives 4.0 International Licence. For details go to http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. Library of Congress Control Number: 2020943602 Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available on the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de. © 2021 Paul Ferstl, published by Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston The book is published open access at www.degruyter.com Cover: Andreas Homann, www.andreashomann.de Typesetting: Dörlemann Satz, Lemförde Printing and binding: CPI books GmbH, Leck www.degruyter.com Table of Contents Paul Ferstl Introduction: Dialogues between Media 1 1 Unsettled Narratives: Graphic Novel and Comics Studies in the Twenty-first Century Stefan Buchenberger, Kai Mikkonen The ICLA Research Committee on Comics Studies and Graphic Narrative: Introduction 13 Angelo Piepoli, Lisa DeTora, Umberto Rossi Unsettled Narratives: Graphic Novel and Comics -

Shakespeare and British Occupation Policy in Germany, 1945-1949

SHAKESPEARE AND BRITISH OCCUPATION POLICY IN GERMANY, 1945-1949 by Katherine Elizabeth Weida B.A. (Washington College) 2011 THESIS / CAPSTONE Submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in HUMANITIES in the GRADUATE SCHOOL of HOOD COLLEGE May 2019 Accepted: ____________________ Dr. Mark Sandona Committee Member ____________________ Dr. Corey Campion ____________________ Program Director Dr. Noel Verzosa, Jr. Committee Member ____________________ ____________________ April M. Boulton, Ph.D Dr. Corey Campion Dean of the Graduate School Capstone Adviser TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction………………………………....3 Chapter 1: Demilitarizing Germany………...22 Chapter 2: Restoring Religion……………....31 Chapter 3: Fostering Humanity…………..…38 Conclusion…………………………………..48 Works Cited………………………………...51 1 ―Shakespeare and British Occupation Policy in Germany, 1945-1949‖ Abstract: Following World War II, the United Kingdom was responsible for occupying a section of Germany. While the British were initially focused on demilitarization and reparations, their goals quickly changed to that of rehabilitation and democratization. In order to accomplish their policy goals, they enlisted the help William Shakespeare, a playwright who had always found favor on the German stage. The British, recognizing that the Germans were hungry for entertainment and were looking for escape, capitalized on this love for Shakespeare by putting his plays back on the stage. Their hope was to influence the Germans into being better members of society by showing them classic plays that aligned with their occupation goals of restoring religion and promoting democracy in the region. Shakespeare‘s timelessness, his ability to reach a broad audience, and the German familiarity with the playwright is the reason why his plays were especially influential in post-World War II Germany. -

Richard Knussert Im National- Sozialismus

Richard Knussert im National- sozialismus Christina Rothenhäusler Inhalt 1. Einleitung ......................................................................................................................................................... 3 2. Knussert als Referent in der Landesstelle Schwaben des RMVP und dem Reichspropagandaamt Schwaben . 6 2.1. Umstrukturierung der Gaukulturarbeit 1936.............................................................................................. 6 2.2. Strukturierung und Aufgaben der Landesstelle Schwaben des RMVP und des Reichspropagandaamts Schwaben .......................................................................................................................................................... 8 2.3. Ernennung Knusserts zum Gaukulturhauptstellenleiter der NSDAP und Referenten für Kulturfragen bei der Landesstelle Schwaben RMVP................................................................................................................. 12 2.4. Programmleitung der Ersten Schwäbischen Gaukulturwoche ................................................................. 19 2.4.1. Die Einbindung der Gaukulturwoche in die nationalsozialistische Kulturpolitik ............................. 19 2.4.2. Knusserts antisemitischer Bericht zur Gaukulturwoche ................................................................... 26 2.5. Kontrolle des regionalen Kulturlebens .................................................................................................... 31 2.5.1. Unterstützung und Kontrolle -

Download Here

THE CAUCASIAN CHALK CIRCLE Written by Catherine Greenwood TEACHER RESOURCE PACK FOR TEACHERS WORKING WITH STUDENTS IN YEAR 7+ THE CAUCASIAN CHALK CIRCLE TERRIBLE IS THE TEMPTATION TO DO GOOD. By Bertolt Brecht A version by Frank McGuinness Directed by Amy Leach Blood runs through the streets and the Governor’s severed head is nailed to gates of the city. A young servant girl must make a choice: save her own skin or sacrifice everything to rescue an abandoned child… A time of terror, followed by a time of peace. Order has been restored and the Governor’s Wife returns to reclaim the son she left behind. Now the choice is the judge’s: who is the real mother of the forgotten child? A bold and inventive new production of Brecht’s moral masterpiece, accompanied by a live and original soundtrack. Page 2 THE CAUCASIAN CHALK CIRCLE CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 4 SECTION ONE: CONTEXT A SUMMARY OF THE PLAY 6 HISTORICAL CONTEXT 9 VIDEO INSIGHTS 10 BRECHT’S LIFE IN BRIEF: TIMELINE 11 BRECHTIAN THEATRE 12 MAKING THE PLAY: INTERVIEWS WITH THE CREATIVE TEAM 16 THE CAST 22 SECTION TWO: DRAMA SESSIONS INTRODUCTION 23 SESSION 1: BRECHT AND POLITICAL THEATRE 24 Resource: Agreement Line 26 SESSION 2: THE PROLOGUE 27 Resource: Prologue Story Whoosh 29 Resource: Information about the two collectives 30 SESSION 3: PERFORMING BRECHT 31 SESSION 4: THE STORY OF AZDAK 33 Resource: Story Whoosh - How Azdak Became Judge 35 SESSION 5: GRUSHA TAKES THE BABY 37 Resource: Story Whoosh - Grusha’s decision 38 Page 3 THE CAUCASIAN CHALK CIRCLE INTRODUCTION Welcome to the Unicorn teacher resources for The Caucasian Chalk Circle by Bertolt Brecht.