By ROSLYN OADES

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

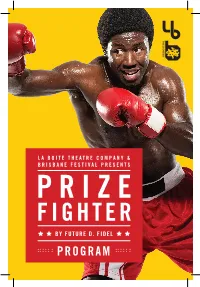

PROGRAM Prize Fighter

LA BOITE THEATRE COMPANY & BRISBANE FESTIVAL PRESENTS PRIZE FIGHTER BY FUTURE D. FIDEL PROGRAM Presented by La Boite Theatre Company & Brisbane Festival 5 - 26 September 2015 at the Roundhouse Theatre CAST Luke, Ensemble Margi Brown-Ash Rita, Nyota, Sofia, Ensemble Sophia Emberson-Bain Kadogo, Tim, Ensemble Thuso Lekwape Moses, Matete, Jeff Wilkie, Ensemble Gideon Mzembe Isa Pacharo Mzembe Aunty, Alaki, Old Man, Wayne Durain, Ensemble Kenneth Ransom PRODUCTION TEAM Writer Future D Fidel Director Todd MacDonald Dramaturg Chris Kohn Designer Bill Haycock Lighting Designer David Walters Composer/Sound Designer Felix Cross Video Designer optikal bloc Movement & Fight Director Nigel Poulton Design Intern Hahnie Goldfinch Lighting Design Secondment Christine Felmingham Stage Manager Heather O’Keeffe Assistant Stage Manager Ariana O’Brien Rehearsal Photography Dylan Evans Special thanks to Emmanuel Otti, Brisbane Boxing, Coleman Tyre Company Wacol and Corporate Box Gym. 1 WRITER’S NOTES Future D. Fidel In the world that depends on technology, it is hard to miss breaking news on an 8.9 Magnitude Earthquake that kills 19 people or the news about a massacre of five people in the middle of Europe. Surprisingly enough, if I asked you about one of the greatest mass killings in the world after WWII, I wouldn’t be surprised if you said the war in Iraq, Afghanistan or Pakistan. The death toll in these three countries combined is recorded to be approximately 371,000 people since 2001according to Watson Institute – Cost of War. This is not close to half the great genocide of Rwanda that claimed almost a million lives. The Democratic Republic of Congo is well known for its richness in natural resources and minerals such as gold, diamond, coltan, petroleum to name a few. -

50 Years of the Stables Griffin Theatre Podcast Series

50 Years of the Stables Griffin Theatre Podcast Series Episode Ten: Writing from the Heart With David Berthold and Tommy Murphy Director David Berthold and playwright Tommy Murphy discuss the pressures of adapting Timothy Conigrave’s beautiful memoir Holding the Man for the Stables stage, the deep emotional currency that the piece holds, and their interactions with Timothy’s family in the process. Host: AC - Angela Catterns Guests: DB - David Berthold TM - Tommy Murphy Angela Catterns: 2020 marks the 50th birthday of Griffin Theatres Company home: the Stables Theatre. I’m Angela Catterns. Join us as we celebrate the anniversary in this special series of podcasts, where we’ll hear about the theatre’s history and talk to some of the country’s most celebrated artists. Angela Catterns (AC): In more than 30 years of Griffin Theatre Company at the Stables Theatre, no production has been more successful than Holding the Man. The original production, adapted for the stage by Tommy Murphy, and directed by David Berthold, premiered in 2006 in a critically- acclaimed, sold out season. Tommy Murphy and David Berthold, both on tight travel schedules, joined us separately, but within hours of each other for this podcast; part of the series celebrating 50 Years of the Stables. AC: Welcome David, thank you for finding time to join our podcast series. David Berthold (DB): Great to be here Angela. AC: Thank you. So, you grew up in the theatre I read, is that right? DB: Um, well only to the extent that quite early on in my life I became involved in amateur drama in um, in Newcastle. -

2013 NIDA Annual Report

NATIONAL INSTITUTE OF DRAMATIC ART THEATRE FILM TELEVISION 215 ANZAC PARADE KENSINGTON NSW 2033 POST NIDA UNSW SYDNEY NSW 2052 PHONE 02 9697 7600 2013 NIDA Annual Report FAX 02 9662 7415 EMAIL [email protected] ABN 99 000 257 741 NATIONAL INSTITUTE OF DRAMATIC ART Theatre, Film, Television WWW.NIDA.EDU.AU ABOUT NIDA The National Institute of Dramatic Art (NIDA) is a public, not-for-profit company and is accorded its national status as an elite training institution by the Australian Government. CONTENTS We continue our historical association with the University of New South Wales and maintain FROM THE CHAIRMAN 4 strong links with national and international arts training organisations, particularly through membership of the Australian Roundtable for Arts Training Excellence (ARTATE) and through FROM THE DIRECTOR / CEO 5 industry partners, which include theatre, dance and opera companies, cultural festivals and UNDERGRADUATE STUDIES 8 film and television producers. NIDA delivers education and training that is characterised by quality, diversity, innovation GRADUATE STUDIES 10 and equity of access. Our focus on practice-based teaching and learning is designed to HIGHER EDUCATION STATISTICS 11 provide the strongest foundations for graduate employment across a broad range of career opportunities and contexts. NIDA OPEN 12 Entry to NIDA’s higher education courses is highly competitive, with around 2,000 NIDA OPEN STATISTICS 13 applicants from across the country competing for an annual offering of approximately 75 places across undergraduate and graduate disciplines. The student body for these PRODUCTIONS AND EVENTS AT courses totalled 166 in 2013. NIDA PARADE THEATRES 14 NIDA is funded by the Australian Government through the Ministry for the Arts, DEVELOPMENT 15 Attorney-General’s Department, and is specifically charged with the delivery of performing arts education and training at an elite level. -

CAST BIOGRAPHIES TOBY STEPHENS (Captain Flint)

-Season Three- CAST BIOGRAPHIES TOBY STEPHENS (Captain Flint) Toby Stephens was born in London, England and trained at the London Academy of Music and Dramatic Art (LAMDA). He has gained critical acclaim as a stage and screen actor and upcoming work includes the feature film 13 Hours: The Secret Soldiers of Benghazi directed by Michael Bay, and And Then There Were None for the BBC. He will also star opposite Timothy Spall and John Hurt in Nick Hamm’s The Journey. Previous television roles include: “Vexed” (BBC), “Robin Hood” (BBC), “Wired” (ITV), “The Wild West” (BBC 1), “Jane Eyre” (BBC 1), “Sharpe’s Challenge” (ITV), “The Best Man” (ITV), “The Queen’s Sister” (Channel 4), “Waking the Dead” (BBC 1), “Poirot” (ITV), “Cambridge Spies” (BBC 2), “Perfect Strangers” (BBC 2), and “The Tenant of Wildfell Hall” (BBC 1). Recent film credits include: Believe with Natasha McElhone and Brian Cox, All Things to All Men alongside Gabriel Byrne and Rufus Sewell, and the lead role in The Machine for Content Film. Other film work includes: Severance, The Rising: Ballad of Mangal Pandey, Die Another Day, Possession, The Announcement, Onegin, Photographing Fairies, Sunset Heights, Cousin Bette, The Great Gatsby, Twelfth Night, and Orlando. Toby is an accomplished stage actor, both in London’s West End and on Broadway. Theater credits include ‘Elyot’ opposite Anna Chancellor in “Noel Coward’s Private Lives,” ‘Georges Danton’ in “Danton’s Death” (National Theatre Olivier), ‘Henry’ in “The Real Thing” (The Old Vic), ‘Thomas’ in “A Doll’s House,” ‘Jerry’ in -

Embargoed to 7Pm 3 Sept

MEDIA RELEASE August 2016 EMBARGOED TO 7PM 3 SEPT. Belvoir’s Artistic Director Eamon Flack has unveiled an optimistic and wildly entertaining season of plays for the company’s 2017 Season. There are inventive new plays from Australia and around the world, there are return seasons and tours of popular plays and two of our favourite stage actors in two great classics. Toby Schmitz returns to the Belvoir stage, after a three year absence, in The Rover by Aphra Behn. Schmitz takes the swashbuckling titular role in this raucous and outrageous battle of the sexes from the woman widely considered the first professional female playwright. Flack has reunited his award-winning team from his 2014 sell out hit The Glass Menagerie to find the same freshness and beauty in Henrik Ibsen’s Ghosts. Pamela Rabe stars as the fierce mother Helene Alving. ‘Our 2016 Season has been very much about reflecting on our past, both for Belvoir and in a wider cultural sense,’ says Flack. ‘With the 2017 Season we are taking an imaginative leap into the future. In this season, characters dream big in the midst of disaster and confusion. They fight passionately for a brighter future. This is a season of plays that unleashes the possibility that maybe the 21st century won’t be an unmitigated disaster.’ Two of the most inventive and exciting plays out of New York’s Playwrights Horizons in recent years are Hir by Taylor Mac and Anne Washburn’s Mr Burns, a Post-Electric Play, and they are both in our 2017 Season. -

Season Two- CAST BIOGRAPHIES TOBY STEPHENS (Captain Flint)

-Season Two- CAST BIOGRAPHIES TOBY STEPHENS (Captain Flint) Toby Stephens was born in London, England and trained at the London Academy of Music and Dramatic Art (LAMDA). He has gained critical acclaim as a stage and screen actor. In 2011, Toby starred as ‘Jack Armstrong’ in the BBC Comedy Drama “Vexed.” Previous television roles include “Robin Hood” (BBC), “Wired” (ITV), “The Wild West” (BBC 1), “Jane Eyre” (BBC 1), “Sharpe’s Challenge” (ITV), “The Best Man” (ITV), “The Queen’s Sister” (Channel 4), “Waking the Dead” (BBC 1), “Poirot” (ITV), “Cambridge Spies” (BBC 2), “Perfect Strangers” (BBC 2), and “The Tenant of Wildfell Hall” (BBC 1). In 2012 Toby filmed Believe with Natasha McElhone and Brian Cox, and in 2013 starred as one of the leads in All Things to All Men alongside Gabriel Byrne and Rufus Sewell. Toby also wrapped filming in Caradog James’ The Machine for Content Film. Other film work includes: Severance, The Rising: Ballad of Mangal Pandey, Die Another Day, Possession, The Announcement, Onegin, Photographing Fairies, Sunset Heights, Cousin Bette, The Great Gatsby, Twelfth Night, and Orlando. Toby is an accomplished stage actor – both in London’s West End and on Broadway. Theater credits include ‘Elyot’ opposite Anna Chancellor in “Noel Coward’s Private Lives,” ‘Georges Danton’ in “Danton’s Death” (National Theatre Olivier), ‘Henry’ in “The Real Thing” (The Old Vic), ‘Thomas’ in “A Doll’s House” and ‘Jerry’ in “Betrayal” (Donmar Warehouse), ‘Mr. Horner’ in “The Country Wife,” ‘Anthony Cavendish’ in “The Royal Family,” ‘Japes’ -

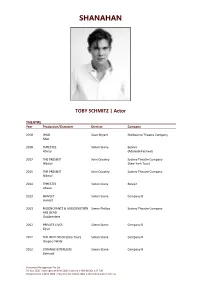

Toby Schmitz CV

SHANAHAN TOBY SCHMITZ | Actor THEATRE Year Production/Character Director Company 2018 DANCE OF DEATH Judy Davis Belvoir Kurt 2018 WILD Dean Bryant Melbourne Theatre Company Man 2018 THYESTES Simon Stone Belvoir Atreus (Adelaide Festival) 2017 THE PRESENT John Crowley Sydney Theatre Company Nikolai (New York Tour) 2015 THE PRESENT John Crowley Sydney Theatre Company Nikolai 2014 THYESTES Simon Stone Belvoir Atreus 2013 HAMLET Simon Stone Company B Hamlet 2013 ROSENCRANTZ & GUILDENSTERN Simon Phillips Sydney Theatre Company ARE DEAD Guildenstern 2012 PRIVATE LIVES Simon Stone Company B Elyot 2012 THE WILD DUCK (Oslo Tour) Simon Stone Company B Gregers Werle Shanahan Management Pty Ltd PO Box 1509 | Darlinghurst NSW 1300 Australia | ABN 46 001 117 728 Telephone 61 2 8202 1800 | Facsimile 61 2 8202 1801 | [email protected] SHANAHAN 2012 STRANGE INTERLUDE Simon Stone Company B Edmund 2012 THE WILD DUCK Simon Stone Malthouse Season Gregers Werle 2011 MUCH ADO ABOUT NOTHING John Bell Bell Shakespeare Benedick 2011 THE WILD DUCK Simon Stone Company B Gregers Werle 2010 MEASURE FOR MEASURE Benedict Andrews Company B Lucio 2010 HAMLET David Berthold La Boite Theatre Company Hamlet 2009 TRAVESTIES Richard Cottrell Sydney Theatre Company Tristan Tzara 2009 RUBEN GUTHRIE Wayne Blair Company B Ruben Guthrie 2008 RABBIT Brendan Cowell Sydney Theatre Company Richard 2008 THE GREAT Peter Evans Sydney Theatre Company Peter & Didi 2008 RUBEN GUTHRIE Wayne Blair Company B Ruben Guthrie 2007 SELF ESTEEM Brendan Cowell Sydney Theatre Company Chad 2006 -

Chloe Armstrong

SHANAHAN DALE FERGUSON | Designer Dale graduated from the National Institute of Dramatic Art in with a Diploma of Dramatic Art, Design in 1989 and a Bachelor of Dramatic Art, Design in 2002. He was Resident Designer at the Queensland Theatre Company from 1990 to 1994 and Resident Designer at the Melbourne Theatre Company from 1995 to 1998 THEATRE Year Production/Position Director Company 2020 EMERALD CITY Sam Strong Queensland Theatre Company Designer 2019 COSI Sarah Goodes Sydney Theatre Company Set Designer 2019 L’APPARTEMENT Joanna Murray-Smith Queensland Theatre Company Designer 2018 COUNTING AND CRACKING Eamon Flack Belvoir St Theatre Set and Costume Designer 2018 AN IDEAL HUSBAND Dean Bryant Melbourne Theatre Company Set and Costume Designer 2018 THE DRESSMAKER Suzanne Chaundy Monash University Theatrical, Scenic and Set Designer Alexander Theatre 2018 BROTHER’S WRECK Jada Alberts Malthouse Theatre Set and Costume Designer 2018 SAMI IN PARADISE Eamon Flack Belvoir St Theatre Set and Costume Designer Shanahan Management Pty Ltd PO Box 1509 | Darlinghurst NSW 1300 Australia | ABN 46 001 117 728 Telephone 61 2 8202 1800 | Facsimile 61 2 8202 1801 | [email protected] SHANAHAN 2017 DI & VIV & ROSE Marion Potts Melbourne Theatre Company Designer 2017 BORN YESTERDAY Dean Bryant Melbourne Theatre Company Set and Costume Designer 2017 AWAY Matthew Lutton Sydney Theatre Company Designer 2016 THE BEAST Simon Phillips Ambassador Theatre Group Designer 2016 SKYLIGHT Dean Bryant Melbourne Theatre Company Designer 2016 THE BLIND GIANT IS DANCING -

TOBY SCHMITZ | Actor

SHANAHAN TOBY SCHMITZ | Actor THEATRE Year Production/Character Director Company 2018 WILD Dean Bryant Melbourne Theatre Company Man 2018 THYESTES Simon Stone Belvoir Atreus (Adelaide Festival) 2017 THE PRESENT John Crowley Sydney Theatre Company Nikolai (New York Tour) 2015 THE PRESENT John Crowley Sydney Theatre Company Nikolai 2014 THYESTES Simon Stone Belvoir Atreus 2013 HAMLET Simon Stone Company B Hamlet 2013 ROSENCRANTZ & GUILDENSTERN Simon Phillips Sydney Theatre Company ARE DEAD Guildenstern 2012 PRIVATE LIVES Simon Stone Company B Elyot 2012 THE WILD DUCK (Oslo Tour) Simon Stone Company B Gregers Werle 2012 STRANGE INTERLUDE Simon Stone Company B Edmund Shanahan Management Pty Ltd PO Box 1509 | Darlinghurst NSW 1300 Australia | ABN 46 001 117 728 Telephone 61 2 8202 1800 | Facsimile 61 2 8202 1801 | [email protected] SHANAHAN 2012 THE WILD DUCK Simon Stone Malthouse Season Gregers Werle 2011 MUCH ADO ABOUT NOTHING John Bell Bell Shakespeare Benedick 2011 THE WILD DUCK Simon Stone Company B Gregers Werle 2010 MEASURE FOR MEASURE Benedict Andrews Company B Lucio 2010 HAMLET David Berthold La Boite Theatre Company Hamlet 2009 TRAVESTIES Richard Cottrell Sydney Theatre Company Tristan Tzara 2009 RUBEN GUTHRIE Wayne Blair Company B Ruben Guthrie 2008 RABBIT Brendan Cowell Sydney Theatre Company Richard 2008 THE GREAT Peter Evans Sydney Theatre Company Peter & Didi 2008 RUBEN GUTHRIE Wayne Blair Company B Ruben Guthrie 2007 SELF ESTEEM Brendan Cowell Sydney Theatre Company Chad 2006 THE EMPEROR OF SYDNEY David Berthold Griffin -

Anthony Phelan

ANTHONY PHELAN THEATRE 2019 BOY SWALLOWS UNIVERSE Queensland Theatre Dir: Sam Strong (Creative Development) 2017 MIRACLE CITY (Millard Sizemore) Sydney Opera House Studio Dir: Darren Yap 2016 TWELFTH NIGHT (Aguecheek) Company B. Belvoir St Dir: Eamon Flack THE WILD DUCK (Ekdal) Perth Intl Arts Festival Dir: Anne-Louise Sarks 2015 MOTHER COURAGE AND HER CHILDREN Company B. Belvoir St Dir: Eamon Flack (Chaplain and as cast) 2014 ONCE IN ROYAL DAVID’S CITY Company B Belvoir St Dir: Eamon Flack (Bill, Wally) 2013 HAMLET (Hamlet’s Ghost) Company B Belvoir St Dir: Simon Stone THE WILD DUCK (Ekdal) Vienna and Amsterdam Dir: Simon Stone 2012 THE WILD DUCK (Ekdal) The Ibsen Festival, Oslo Dir: Simon Stone THE WILD DUCK (Ekdal) Malthouse Theatre Dir: Simon Stone UNCLE VANYA Lincoln Centre Festival, NYCDir: Tamas Ascher STRANGE INTERLUDE (Father) Company B. Belvoir St. Dir: Simon Stone 2011 UNCLE VANYA (Telegin) The Kennedy Centre Festival, Washington D.C. Dir: Simon Stone. **THE WILD DUCK (Ekdal) Company B. Belvoir St. Dir: Simon Stone 2010 UNCLE VANYA (Telegin) Sydney Theatre Co. Dir: Tamas Ascher KING LEAR (Duke of Cornwell/Ensemble) Bell Shakespeare Co. Dir: Marion Potts 2009 THE WHITE EARTH (John Mclvor) LaBoite Theatre Co. Dir: Shaun Charles 2008 STRANGERS IN BETWEEN (Peter) Griffin Theatre Co. Dir: David Berthold FEMALE OF THE SPECIES (Theo Hanover) Queensland Theatre Co. Dir: Kate Cherry 2006 THE SEED (Reading) Company B Belvoir Street Theatre 2005 MARVELLOUS BOY Griffin Theatre Co. Dir: David Berthold JULIUS CAESAR (Casca) The Sydney Theatre Co. Dir: Benedict Andrews STRANGERS IN BETWEEN (Peter) Griffin Theatre Co. -

Putting Hamlet in a Hoodie: Critical Issues in Contemporising Shakespeare Through Costume Design

98 Putting Hamlet in a hoodie: Critical issues in contemporising Shakespeare through costume design Madeline Taylor Madeline Taylor is a Sessional Lecturer and Tutor at the Queensland University of Technology and a Co-Director of the stitchery collective. She is both a researcher and creator of theatre. Beginning her theatre industry career at 17, she has since worked on over 75 productions in theatre, dance, opera, circus, contemporary performance and film around Australia and the UK. In 2010 she completed a research internship at the Victoria & Albert Museum under Donatella Barbier. Alongside this she is developing her academic career, completing a dissertation at QUT focused on contemporary costume practice in Australia in 2011 and since taught there in costume and fashion theory. She is also a co- director for fashion and design collective the stitchery and Australian Editor for the World Scenography Project Vol II. Context, argument and approach It is now rare to see a Shakespearean production in Australia performed in doublet and hose. Constantly revived and adapted, over the past few decades these plays have become increasingly likely to be set some time in the 20th or 21st century or in a purposefully vague ‘now’. The reverence with which these texts are treated often means that the scenography carries the burden of conveying the updated time, with costuming frequently bearing the brunt of this weight. In justifying the programming of these revivals this design and directional decision is consistently connected to ideas about universal accessibility, currency and relevancy to contemporary audiences. This paper adds to the longstanding industry and academic debate that surrounds staging Shakespeare and his contemporaries, and which has been written about since at least the 1920s.1 Each time one of these plays is revived the choice of time setting and location must be made by the creative team, usually the director and set and costume designer/s. -

Tess Schofield [email protected] APDG

tess schofield [email protected] APDG . AACTA . MEAA project YEAR director / producer CREDIT FILM & TV THE KETTERING INCIDENT 2014 Directors : Rowan Woods / Tony Krawitz costume designer prod. Vincent Sheehan / Fiona MCConaghy / Andy Walker THE WATER DIVINER 2014 Director : Russell Crowe costume designer Prod. Troy Lum | Andrew Mason | Keith Rodger THE SAPPHIRES 2011 Director : Wayne Blair costume designer Goalpost Pictures DIRTY DEEDS 2001 Director : David Caesar costume designer Prod. Deborah Balderstone & Bryan Brown SUBTERANO 2000 Director : Esben Storm costume designer Prod. Richard Becker and Barbi Taylor BOOTMEN 1999 Director : Dein Perry costume designer Prod. Hilary Linstead MUMBO JUMBO 1998 Director : Catherine Millar costume designer (telefeature) Prod. Helen Watts RADIANCE 1997 Director : Rachel Perkins costume designer Prod. Ned Lander & Andrew Meyer DIANA AND ME 1996 Director : David Parker costume designer Prod. Matt Carroll MR RELIABLE 1995 Director : Nadia Tass costume designer Prod. Jim McElroy & Terry Hayes COSI 1994 Director : Mark Joffe costume designer Prod. Tim White & Richard Brennan GREENKEEPING 1991 Director : David Caesar costume designer Prod. Glenys Rowe SPOTSWOOD 1990 Director : Mark Joffe costume designer Prod. Tim White & Richard Brennan OPERA LA TRAVIATA 2011 Director : Francesca Zambello costume designer (HANDA Opera on Sydney Harbour) Opera Australia PETER GRIMES 2010 Director : Neil Armfield costume designer (remount / Houston Grand Opera) Houston Grand Opera & OA PETER GRIMES 2009 Director