Tantra Enlightenment to Revolution Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Delhi on the Second Consecu- “Seriously Damaging Impact” Imise Extremist Activism,” the December 7, Awards Will Be Tive Day

( B2 $ A # '% C % C C VRGR '%&((!1#VCEB R BP A"'!#$#1!$"#0$"T utqBVQWBuxy( 35&63% ., 2$1213 42 , 5$2 /6 A $/4O2"EE H-2-5587"E/824/5-7&E-2&/4 &4$&-"-2-8E9 $"71&780?4/6 1/A-718-4"E6-5 6&21-5"5E /&E5-"72&"E/54/6 584E&4E22,> 5-401&5-&A85 01-4$&3-51 $"15-$84 19$"5--$ &G-96-$- D7 0 $2+>334 ++: D-E " #- 7 ) " 0 1-1- ! 1/ R R R ! " ( ! 4"6$"71& soon. In the meeting tomorrow our main agenda will be to he farmers on Friday called know if the Government is Tfor “Bharat Bandh” on rolling back laws or not. The December 8 to mark their protests are going on country- authorities to highlight our protest against the new farm wide against the law, even in # # # concerns.” laws if their talks with the Andhra Pradesh and Telangana Q % & R The External Affairs Centre fail. Thousands of farm- and this protest is just not lim- Ministry said these comments ers remained at the national ited to northern States but have encouraged gatherings of Capital’s border points amid across the country,” said '() “extremist activities” in front of heavy police deployment. Ranjeet Singh Raju from our High Commission and “The Government has to Rajasthan. 4"6$"71& Consulates in Canada that raise revoke these laws in a meeting Farmers from western issues of safety and security. scheduled for December 5, Uttar Pradesh and Uttarakhand tepping up its protest against “We expect the Canadian otherwise we have decided to stayed put at Ghazipur border SCanadian Prime Minister Government to ensure the give ‘Bharat bandh’ call on (UP Gate) to mark their Justin Trudeau’s remarks about fullest security of Indian December 8 and we will also protest. -

Music Initiative Jka Peer - Reviewed Journal of Music

VOL. 01 NO. 01 APRIL 2018 MUSIC INITIATIVE JKA PEER - REVIEWED JOURNAL OF MUSIC PUBLISHED,PRINTED & OWNED BY HIGHER EDUCATION DEPARTMENT, J&K CIVIL SECRETARIAT, JAMMU/SRINAGAR,J&K CONTACT NO.S: 01912542880,01942506062 www.jkhighereducation.nic.in EDITOR DR. ASGAR HASSAN SAMOON (IAS) PRINCIPAL SECRETARY HIGHER EDUCATION GOVT. OF JAMMU & KASHMIR YOOR HIGHER EDUCATION,J&K NOT FOR SALE COVER DESIGN: NAUSHAD H GA JK MUSIC INITIATIVE A PEER - REVIEWED JOURNAL OF MUSIC INSTRUCTION TO CONTRIBUTORS A soft copy of the manuscript should be submitted to the Editor of the journal in Microsoft Word le format. All the manuscripts will be blindly reviewed and published after referee's comments and nally after Editor's acceptance. To avoid delay in publication process, the papers will not be sent back to the corresponding author for proof reading. It is therefore the responsibility of the authors to send good quality papers in strict compliance with the journal guidelines. JK Music Initiative is a quarterly publication of MANUSCRIPT GUIDELINES Higher Education Department, Authors preparing submissions are asked to read and follow these guidelines strictly: Govt. of Jammu and Kashmir (JKHED). Length All manuscripts published herein represent Research papers should be between 3000- 6000 words long including notes, bibliography and captions to the opinion of the authors and do not reect the ofcial policy illustrations. Manuscripts must be typed in double space throughout including abstract, text, references, tables, and gures. of JKHED or institution with which the authors are afliated unless this is clearly specied. Individual authors Format are responsible for the originality and genuineness of the work Documents should be produced in MS Word, using a single font for text and headings, left hand justication only and no embedded formatting of capitals, spacing etc. -

The KNIGHT REVISION of HORNBOSTEL-SACHS: a New Look at Musical Instrument Classification

The KNIGHT REVISION of HORNBOSTEL-SACHS: a new look at musical instrument classification by Roderic C. Knight, Professor of Ethnomusicology Oberlin College Conservatory of Music, © 2015, Rev. 2017 Introduction The year 2015 marks the beginning of the second century for Hornbostel-Sachs, the venerable classification system for musical instruments, created by Erich M. von Hornbostel and Curt Sachs as Systematik der Musikinstrumente in 1914. In addition to pursuing their own interest in the subject, the authors were answering a need for museum scientists and musicologists to accurately identify musical instruments that were being brought to museums from around the globe. As a guiding principle for their classification, they focused on the mechanism by which an instrument sets the air in motion. The idea was not new. The Indian sage Bharata, working nearly 2000 years earlier, in compiling the knowledge of his era on dance, drama and music in the treatise Natyashastra, (ca. 200 C.E.) grouped musical instruments into four great classes, or vadya, based on this very idea: sushira, instruments you blow into; tata, instruments with strings to set the air in motion; avanaddha, instruments with membranes (i.e. drums), and ghana, instruments, usually of metal, that you strike. (This itemization and Bharata’s further discussion of the instruments is in Chapter 28 of the Natyashastra, first translated into English in 1961 by Manomohan Ghosh (Calcutta: The Asiatic Society, v.2). The immediate predecessor of the Systematik was a catalog for a newly-acquired collection at the Royal Conservatory of Music in Brussels. The collection included a large number of instruments from India, and the curator, Victor-Charles Mahillon, familiar with the Indian four-part system, decided to apply it in preparing his catalog, published in 1880 (this is best documented by Nazir Jairazbhoy in Selected Reports in Ethnomusicology – see 1990 in the timeline below). -

Sapta Matrikas Bharati Pal

Orissa Review September - 2009 Sapta Matrikas Bharati Pal The Sapta Matrikas or the seven divine mothers, weild the trisula in one of her hands and carry a representing the saktis, or the energies of the kapala in another. All the Matrikas are to be important familiar deities are Brahmani (Saraswati) seated images and should have two of their hands Mahesvari (Raudani) Kaumari (Karttikeyani) held in the Varada and Abhaya poses, while the Vaishnavi (Lakshmi) Varahi, Indrani and other two hands carry weapons appropriate to Chamunda (Chamundi). According to a legend the male counterparts of the female powers. described in the Isanasivagurudevapaddhati, The Varaha Purana states that these the Matrikas were created to help Lord Siva in mother-goddesses are eight in number and his fight against Andhakasura. When the Lord includes among them the goddess Yogesvari. It inflicted wounds on Andhaka, blood began to flow further says that these Matrikas represent eight profusely from his body. Each drop which touched mental qualities which are morally bad. the ground assumed the shape of another Accordingly, Yogesvari represents kama or Andhaka. Thus there were innumerable Asuras desire; Mahesvari, krodh or anger; Vaishnavi, fighting Siva. To stop the flow of the blood, Siva lobha or covetousness; Brahmani; mada or created a goddess called Yogesvari from the pride; Kaumari moha or illusion; Indrani, flames issuing out of his mouth. Brahma, Vishnu, matsarya or fault finding; Yami or Chumunda Maheswara, Kumara, Varaha, Indra and Yama paisunya, that is tale bearing; and Varahi asuya also sent their saktis to follow Yogesvari in or envy. stopping the flow of blood. -

Guide to 275 SIVA STHALAMS Glorified by Thevaram Hymns (Pathigams) of Nayanmars

Guide to 275 SIVA STHALAMS Glorified by Thevaram Hymns (Pathigams) of Nayanmars -****- by Tamarapu Sampath Kumaran About the Author: Mr T Sampath Kumaran is a freelance writer. He regularly contributes articles on Management, Business, Ancient Temples and Temple Architecture to many leading Dailies and Magazines. His articles for the young is very popular in “The Young World section” of THE HINDU. He was associated in the production of two Documentary films on Nava Tirupathi Temples, and Tirukkurungudi Temple in Tamilnadu. His book on “The Path of Ramanuja”, and “The Guide to 108 Divya Desams” in book form on the CD, has been well received in the religious circle. Preface: Tirth Yatras or pilgrimages have been an integral part of Hinduism. Pilgrimages are considered quite important by the ritualistic followers of Sanathana dharma. There are a few centers of sacredness, which are held at high esteem by the ardent devotees who dream to travel and worship God in these holy places. All these holy sites have some mythological significance attached to them. When people go to a temple, they say they go for Darsan – of the image of the presiding deity. The pinnacle act of Hindu worship is to stand in the presence of the deity and to look upon the image so as to see and be seen by the deity and to gain the blessings. There are thousands of Siva sthalams- pilgrimage sites - renowned for their divine images. And it is for the Darsan of these divine images as well the pilgrimage places themselves - which are believed to be the natural places where Gods have dwelled - the pilgrimage is made. -

An Analysis of Tantric Practices at Kamakhya and Tarapith

International Journal of Applied Research 2018; 4(4): 39-41 ISSN Print: 2394-7500 ISSN Online: 2394-5869 Impact Factor: 5.2 Re-examining the cult of the feminine: An analysis of IJAR 2018; 4(4): 39-41 www.allresearchjournal.com tantric practices at Kamakhya and Tarapith Received: 15-02-2018 Accepted: 17-03-2018 Dr. Chandni Sengupta Dr Chandni Sengupta Assistant Professor, Department of History, Amity Abstract School of Liberal Arts, Amity Tantricism is inextricably inter-linked with the cult of the feminine. Tantric rituals exalt the female University Haryana, Haryana, deity and celebrate the power (Shakti) of the female form of divinity. In India, alongside the Vedic India system of worship, Tantricism has co-existed for centuries. There are references to the Tantric tradition in the epics; similar references have also been found in the Indus Valley civilization. There are many shakti peeths in India but only a few are associated with Tantricism. This article aims to explore the Tantric rituals at the temples of Kamakhya in Assam and Tarapith in West Bengal, in order to establish the significance of the Tantric tradition even in the 21st century. Keywords: tantricism, tantra, ritual, goddess, Shakti, Devi, cult, practices Introduction In India, since the ancient time, two distinct and parallel forms of worship have existed- Vedic and Non-Vedic. Kallukabhatta, the first scholar who presented an exhaustive interpretation of the Manusmriti, made a clear distinction between two branches of Indian thought. He divided Indian wisdom into Vedic and Tantric [1]. The former was based on a male-centric social order, while the latter was based on the principles of matriarchy and consequently the notions of fertility. -

Tathagata-Garbha Sutra

Tathagata-garbha Sutra (Tripitaka No. 0666) Translated during the East-JIN Dynasty by Tripitaka Master Buddhabhadra from India Thus I heard one time: The Bhagavan was staying on Grdhra-kuta near Raja-grha in the lecture hall of a many-tiered pavilion built of fragrant sandalwood. He had attained buddhahood ten years previously and was accompanied by an assembly of hundred thousands of great bhikshus and a throng of bodhisattvas and great beings sixty times the number of sands in the Ganga. All had perfected their zeal and had formerly made offerings to hundred thousands of myriad legions of Buddhas. All could turn the Irreversible Dharma Wheel. If a being were to hear their names, he would become irreversible in the unsurpassed path. Their names were Bodhisattva Dharma-mati, Bodhisattva Simha-mati, Bodhisattva Vajra-mati, Bodhisattva Harmoniously Minded, bodhisattva Shri-mati, Bodhisattva Candra- prabha, Bodhisattva Ratna-prabha, Bodhisattva Purna-candra, Bodhisattva Vikrama, Bodhisattva Ananta-vikramin, Bodhisattva Trailokya-vikramin, Bodhisattva Avalokiteshvara, Bodhisattva Maha-sthama-prapta, Bodhisattva Gandha-hastin, Bodhisattva Sugandha, Bodhisattva Surpassing Sublime Fragrance, Bodhisattva Supreme matrix, Bodhisattva Surya-garbha, Bodhisattva Ensign Adornment, Bodhisattva Great Arrayed Banner, Bodhisattva Vimala-ketu, Bodhisattva Boundless Light, Bodhisattva Light Giver, Bodhisattva Vimala-prabha, Bodhisattva Pramudita-raja, Bodhisattva Sada-pramudita, Bodhisattva Ratna-pani, Bodhisattva Akasha-garbha, Bodhisattva King of the Light -

Health Providers in India

Downloaded by [University of Defence] at 01:14 24 May 2016 Health Providers in India Downloaded by [University of Defence] at 01:14 24 May 2016 (ii) Blank Downloaded by [University of Defence] at 01:14 24 May 2016 Health Providers in India On the Frontlines of Change Editors Kabir Sheikh and Asha George Downloaded by [University of Defence] at 01:14 24 May 2016 First published 2010 By Routledge 912–915 Tolstoy House, 15–17 Tolstoy Marg, New Delhi 110 001 Simultaneously published in UK by Routledge 2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, OX14 4RN Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business © 2010 Kabir Sheikh and Asha George Typeset by Bukprint India B-180A Guru Nanak Pura, Laxmi Nagar, Delhi 110 092 Printed and bound in India by Sanat Printers 312 EPIP Kundli, Haryana 131 028 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage and retrieval system without permission in writing from the publishers. Downloaded by [University of Defence] at 01:14 24 May 2016 British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data A catalogue record of this book is available from the British Library ISBN: 978-0-415-57977-3 Advance Praise for the Book This excellent collection of new work begins to fill a major gap in our understanding of key features of the Indian health system: Who fill its positions, formal and informal, public and private sector, trained and untrained? What are their motivations, their ideals, and the everyday realities of their experiences? And how do these accommodate to, coalesce with, or conflict with major national health goals? Sheikh and George are to be congratulated for their initiative in stimulating contributors to such a well- constructed volume — one that will undoubtedly set the agenda for health-related policy-relevant research in India over the next decade. -

The Practice of the Guru Who Holds the Power of Life ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !

! ! ! ! ! ! ! !,!!,]-3- 5K- .2%- :6B/- 0:A- =?- L%- 28$?- ?R,, The Practice of the Guru Who Holds the Power of Life ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! BUDDHA VISIONS PRESS Portland, Oregon www.buddhavisions.com [email protected] Copyright © 2015 by Eric Fry-Miller. All rights reserved. !,!!,5K:A- .2%- 0R- :6B/- 0- ]- 3- $?%- 2:A- 12- ,2?- GA- =?- L%- /A,!!$/?- .2J/- 0<- 0E- S$- 0R:C- VA?- {:A- 3./- .- $+R<- 3- 0.- :.2- 28A- 0:A- !J%- .,!<A=- 2- $?3- IA- !J%- .- <A=- 2- /R<- 2:A- .LA2?- &/- 28$- &A%- ,!!0E:A- 3,<- <A=- 2?- 2{R<- 2- .!<- .3<- IA?- 2o/- 0- .%- , (/- <!- 3(R.- $+R<- 2>3?,!!<R=- 3R:C- LJ- V$- :.- L?,!!12- 0R- #- zR- /2- +- KR$?- 0?,! As for the Secret Sadhana Practice of the Guru who holds the Power of Life, in a solitary place before a painting of the Wrathful Lotus Guru, Pema Dragpo, set out a torma with four petals. On the petals set three spheres. Above that set one sphere that has the shape of a jewel. Circle the perimeter of the lotuses with spheres and adorn with white and red. Set out the offerings of amrita, rakta, and torma. Bring together the various instruments. Facing the southwest, the practitioner goes for refuge. *2?- ?- :PR- 2- /A, Refuge >,!!<%- <A$- $.R.- /?- ]- 3:A- {,!!<A$- 3.%?- :$$- 3J.- =R%?- ,R.- mR$?,!!,<A$- l=- 3=- 0:A- {:A- <%- 28A/,!!,{- $?3- $4S- =- *2?- ?- 3(A,!!,=/- $?3,! HUNG RANG RIG DÖ NE LA MAI KU RIG DANG GAG ME LONG CHÖ DZOG RIG TSAL TRUL PAI KÜ RANG ZHIN KU SUM TSO LA KYAB SU CHI Hung Primordial self-awareness is the kaya of the Guru. -

South-Indian Images of Gods and Goddesses

ASIA II MB- • ! 00/ CORNELL UNIVERSITY* LIBRARY Date Due >Sf{JviVre > -&h—2 RftPP )9 -Af v^r- tjy J A j£ **'lr *7 i !! in ^_ fc-£r Pg&diJBii'* Cornell University Library NB 1001.K92 South-indian images of gods and goddesse 3 1924 022 943 447 AGENTS FOR THE SALE OF MADRAS GOVERNMENT PUBLICATIONS. IN INDIA. A. G. Barraud & Co. (Late A. J. Combridge & Co.)> Madras. R. Cambrav & Co., Calcutta. E. M. Gopalakrishna Kone, Pudumantapam, Madura. Higginbothams (Ltd.), Mount Road, Madras. V. Kalyanarama Iyer & Co., Esplanade, Madras. G. C. Loganatham Brothers, Madras. S. Murthv & Co., Madras. G. A. Natesan & Co., Madras. The Superintendent, Nazair Kanun Hind Press, Allahabad. P. R. Rama Iyer & Co., Madras. D. B. Taraporevala Sons & Co., Bombay. Thacker & Co. (Ltd.), Bombay. Thacker, Spink & Co., Calcutta. S. Vas & Co., Madras. S.P.C.K. Press, Madras. IN THE UNITED KINGDOM. B. H. Blackwell, 50 and 51, Broad Street, Oxford. Constable & Co., 10, Orange Street, Leicester Square, London, W.C. Deighton, Bell & Co. (Ltd.), Cambridge. \ T. Fisher Unwin (Ltd.), j, Adelphi Terrace, London, W.C. Grindlay & Co., 54, Parliament Street, London, S.W. Kegan Paul, Trench, Trubner & Co. (Ltd.), 68—74, iCarter Lane, London, E.C. and 25, Museum Street, London, W.C. Henry S. King & Co., 65, Cornhill, London, E.C. X P. S. King & Son, 2 and 4, Great Smith Street, Westminster, London, S.W.- Luzac & Co., 46, Great Russell Street, London, W.C. B. Quaritch, 11, Grafton Street, New Bond Street, London, W. W. Thacker & Co.^f*Cre<d Lane, London, E.O? *' Oliver and Boyd, Tweeddale Court, Edinburgh. -

Mehran-University-Of-Engineering-Technology-First-Merit-List2 0.Pdf

Full Name Father NameCNIC Enrollemt No.DepartmentCampus Year ofHSC Study percentageLast Exam PercentageCGPA Merit StatusStudent Selection Status Ahmed Bux Nadeem Ahmed4530327652261 CE17AR32 ArchitectureCEAD, MUET, Jamshoro1 82.2 82.18 3.33 Selected Selected Student Khair MuhammadSohail Khalique4410188995737 F-CE17 AR22ArchitectureCEAD, MUET, Jamshoro1 82.1 82.09 3.33 Selected Selected Student Sohaib Qureshi Saifuddin Qureshi4150405257207 F-CE17-AR21ArchitectureCEAD, MUET, Jamshoro1 80.8 80.81 3.28 Selected Selected Student Touqeer Ul HaqueMohammad3810298220957 Arshad CE17AR23 ArchitectureCEAD, MUET, Jamshoro1 80.5 80.54 3.27 Selected Selected Student Tamoor Ali Liquat Ali 4410650947793 CE17AR40 ArchitectureCEAD, MUET, Jamshoro1 80.5 80.45 3.27 Selected Selected Student Ume Aeman Zulfiqar Ali 4120522942830 CE17AR02 ArchitectureCEAD, MUET, Jamshoro1 80.2 80 3.26 Selected Selected Student GH zohra alias pashminaAbdul Raheem4530193395302 memon CE17AR35 ArchitectureCEAD, MUET, Jamshoro1 78.1 78 3.18 Selected Selected Student Sana Laghari Allah Nawaz4410355870786 Laghari 47694 ArchitectureCEAD, MUET, Jamshoro1 77.7 77.72 3.17 Not SelectedNot Selected Iraj Maira BughioNabi Bakhsh4130533257536 Bughio CE17AR38 ArchitectureCEAD, MUET, Jamshoro1 77.8 77.81 3.17 Not SelectedNot Selected Farooq ahmed akhundJamil hyder akhund1412017560343 CE17AR30 ArchitectureCEAD, MUET, Jamshoro1 77.2 77.18 3.15 Not SelectedNot Selected Awais Ahmed Shakeel Ahmed4510288215979 CE17AR39 ArchitectureCEAD, MUET, Jamshoro1 76 76 3.1 Not SelectedNot Selected Aleeha Mehmood -

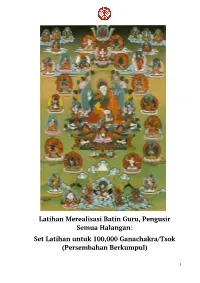

Set Latihan Untuk 100000 Ganachakra/Tsok

Latihan Merealisasi Batin Guru, Pengusir Semua Halangan: Set Latihan untuk 100,000 Ganachakra/Tsok (Persembahan Berkumpul) 1 Daftar Isi Doa Silsilah Doa Tujuh Baris................................................................................3 Doa kepada Para Guru Besar Silsilah Nyingma...............................4 Devosi Lapis Tiga Terang Sinar Matahari .......................................5 Doa kepada Guru Akar.....................................................................8 Sadhana Utama Latihan Harian Esensial༔..................................................................9 Ganachakra/Tsok (Persembahan Berkumpul)..............................15 Gumpalan Awan Dua Akumulasi....................................................15 Akumulasi.......................................................................................18 Dedikasi dan Aspirasi Dedikasi untuk Latihan Harian Esensial:......................................20 Aspirasi Mandala Vajradhātu (chokchu düzhi).............................22 Aspirasi Perkembangan Aktivitas Chokgyur Lingpa.....................32 Penghargaan........................................................................................33 2 DOA SILSILAH ༈ 歲ག་བ䝴ན་ག魼ལ་འ䝺བས་佲། Doa Tujuh Baris ཧཱུྃ༔ ꍼ་རྒྱན་蝴ལ་གྱི་佴བ་宱ང་མཚམས༔ hung༔ orgyen yül gyi nupjang tsam Hūṃ༔ Di barat laut Uḍḍiyāna,༔ པ䞨་་སར་སྡོང་卼་ལ༔ pema gesar dongpo la di tengah bunga teratai,༔ ཡ་མཚན་མ᭼ག་୲་ད፼ས་གྲུབ་བརྙེས༔ yamtsen chokgi ngödrup nyé engkau datang, dikenal sebagai Yang Lahir dari Teratai,༔ པ䞨་འབྱུང་གནས་筺ས་魴་லགས༔ pema jungné