The Baptismal Anointings According to the Anonymous Expositio Officiorum†

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Eastern Rite Catholicism

Eastern Rite Catholicism Religious Practices Religious Items Requirements for Membership Medical Prohibitions Dietary Standards Burial Rituals Sacred Writings Organizational Structure History Theology RELIGIOUS PRACTICES Required Daily Observances. None. However, daily personal prayer is highly recommended. Required Weekly Observances. Participation in the Divine Liturgy (Mass) is required. If the Divine Liturgy is not available, participation in the Latin Rite Mass fulfills the requirement. Required Occasional Observances. The Eastern Rites follow a liturgical calendar, as does the Latin Rite. However, there are significant differences. The Eastern Rites still follow the Julian Calendar, which now has a difference of about 13 days – thus, major feasts fall about 13 days after they do in the West. This could be a point of contention for Eastern Rite inmates practicing Western Rite liturgies. Sensitivity should be maintained by possibly incorporating special prayer on Eastern Rite Holy days into the Mass. Each liturgical season has a focus; i.e., Christmas (Incarnation), Lent (Human Mortality), Easter (Salvation). Be mindful that some very important seasons do not match Western practices; i.e., Christmas and Holy Week. Holy Days. There are about 28 holy days in the Eastern Rites. However, only some require attendance at the Divine Liturgy. In the Byzantine Rite, those requiring attendance are: Epiphany, Ascension, St. Peter and Paul, Assumption of the Blessed Virgin Mary, and Christmas. Of the other 15 solemn and seven simple holy days, attendance is not mandatory but recommended. (1 of 5) In the Ukrainian Rites, the following are obligatory feasts: Circumcision, Easter, Dormition of Mary, Epiphany, Ascension, Immaculate Conception, Annunciation, Pentecost, and Christmas. -

Liturgical Press Style Guide

STYLE GUIDE LITURGICAL PRESS Collegeville, Minnesota www.litpress.org STYLE GUIDE Seventh Edition Prepared by the Editorial and Production Staff of Liturgical Press LITURGICAL PRESS Collegeville, Minnesota www.litpress.org Scripture texts in this work are taken from the New Revised Standard Version Bible: Catholic Edition © 1989, 1993, Division of Christian Education of the National Council of the Churches of Christ in the United States of America. Used by permission. All rights reserved. Cover design by Ann Blattner © 1980, 1983, 1990, 1997, 2001, 2004, 2008 by Order of Saint Benedict, Collegeville, Minnesota. Printed in the United States of America. Contents Introduction 5 To the Author 5 Statement of Aims 5 1. Submitting a Manuscript 7 2. Formatting an Accepted Manuscript 8 3. Style 9 Quotations 10 Bibliography and Notes 11 Capitalization 14 Pronouns 22 Titles in English 22 Foreign-language Titles 22 Titles of Persons 24 Titles of Places and Structures 24 Citing Scripture References 25 Citing the Rule of Benedict 26 Citing Vatican Documents 27 Using Catechetical Material 27 Citing Papal, Curial, Conciliar, and Episcopal Documents 27 Citing the Summa Theologiae 28 Numbers 28 Plurals and Possessives 28 Bias-free Language 28 4. Process of Publication 30 Copyediting and Designing 30 Typesetting and Proofreading 30 Marketing and Advertising 33 3 5. Parts of the Work: Author Responsibilities 33 Front Matter 33 In the Text 35 Back Matter 36 Summary of Author Responsibilities 36 6. Notes for Translators 37 Additions to the Text 37 Rearrangement of the Text 37 Restoring Bibliographical References 37 Sample Permission Letter 38 Sample Release Form 39 4 Introduction To the Author Thank you for choosing Liturgical Press as the possible publisher of your manuscript. -

Dictionary of Byzantine Catholic Terms

~.~~~~- '! 11 GREEK CATHOLIC -reek DICTIONARY atholic • • By 'Ictionary Rev. Basil Shereghy, S.T.D. and f Rev. Vladimir Vancik, S.T.D. ~. J " Pittsburgh Byzantine Diocesan Press by Rev. Basil Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania Shereghy, S.T.D. 1951 • Nihil obstat: To Very Rev. John K. Powell Censor. The Most Reverend Daniel Ivancho, D.D. Imprimatur: t Daniel Ivancho, D.D. Titular Bishop of Europus, Apostolic Exarch. Ordinary of the Pittsburgh Exarchate Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania of the Byzantine.•"Slavonic" Rite October 18, 1951 on the occasion of the solemn blessing of the first Byzantine Catholic Seminary in America this DoaRIer is resf1'eCtfUflY .diditateit Copyright 1952 First Printing, March, 1952 Printed by J. S. Paluch Co•• Inc .• Chicago Greek Catholic Dictionary ~ A Ablution-The cleansing of the Because of abuses, the Agape chalice and the fin,ers of the was suppressed in the Fifth cen• PREFACE celebrant at the DiVIne Liturgy tury. after communion in order to re• As an initial attempt to assemble in dictionary form the more move any particles of the Bless• Akathistnik-A Church book con• common words, usages and expressions of the Byzantine Catholic ed Sacrament that may be ad• taining a collection of akathists. Church, this booklet sets forth to explain in a graphic way the termin• hering thereto. The Ablution Akathistos (i.e., hymns)-A Greek ology of Eastern rite and worship. of the Deacon is performed by term designating a service dur• washmg the palm of the right ing which no one is seated. This Across the seas in the natural home setting of the Byzantine• hand, into .••••.hich the Body of service was originally perform• Slavonic Rite, there was no apparent need to explain the whats, whys Jesus Christ was placed by the ed exclusively in honor of and wherefores of rite and custom. -

St. Ambrose and the Architecture of the Churches of Northern Italy : Ecclesiastical Architecture As a Function of Liturgy

University of Louisville ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository Electronic Theses and Dissertations 12-2008 St. Ambrose and the architecture of the churches of northern Italy : ecclesiastical architecture as a function of liturgy. Sylvia Crenshaw Schneider 1948- University of Louisville Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.louisville.edu/etd Recommended Citation Schneider, Sylvia Crenshaw 1948-, "St. Ambrose and the architecture of the churches of northern Italy : ecclesiastical architecture as a function of liturgy." (2008). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 1275. https://doi.org/10.18297/etd/1275 This Master's Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. This title appears here courtesy of the author, who has retained all other copyrights. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ST. AMBROSE AND THE ARCHITECTURE OF THE CHURCHES OF NORTHERN ITALY: ECCLESIASTICAL ARCHITECTURE AS A FUNCTION OF LITURGY By Sylvia Crenshaw Schneider B.A., University of Missouri, 1970 A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Louisville in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Department of Art History University of Louisville Louisville, Kentucky December 2008 Copyright 2008 by Sylvia A. Schneider All rights reserved ST. AMBROSE AND THE ARCHITECTURE OF THE CHURCHES OF NORTHERN ITALY: ECCLESIASTICAL ARCHITECTURE AS A FUNCTION OF LITURGY By Sylvia Crenshaw Schneider B. A., University of Missouri, 1970 A Thesis Approved on November 22, 2008 By the following Thesis Committee: ____________________________________________ Dr. -

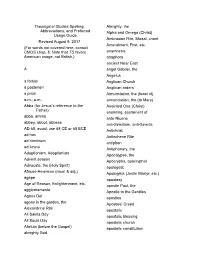

Theological Studies Spelling, Abbreviations, and Preferred Usage

Theological Studies Spelling, Almighty, the Abbreviations, and Preferred Alpha and Omega (Christ) Usage Guide Ambrosian Rite, Missal, chant Revised August 9, 2017 Amendment, First, etc. (For words not covered here, consult CMOS chap. 8. Note that TS favors anamnesis American usage, not British.) anaphora ancient Near East A angel Gabriel, the Angelus a fortiori Anglican Church a posteriori Anglican orders a priori Annunciation, the (feast of) a.m., p.m. annunciation, the (to Mary) Abba (for Jesus’s reference to the Anointed One (Christ) Father) anointing, sacrament of abba, amma ante-Nicene abbey, abbot, abbess anti-Semitism, anti-Semitic AD 68, avoid: use 68 CE or 68 BCE Antichrist ad hoc Antiochene Rite ad hominem antiphon ad limina Antiphonary, the Adoptionism, Adoptionists Apocalypse, the Advent season Apocrypha, apocryphal Advocate, the (Holy Spirit) apologetic African-American (noun & adj.) Apologists (Justin Martyr, etc.) agape apostasy Age of Reason, Enlightenment, etc. apostle Paul, the aggiornamento Apostle to the Gentiles Agnus Dei apostles agony in the garden, the Apostles’ Creed Alexandrine Rite apostolic All Saints Day apostolic blessing All Souls Day apostolic church Alleluia (before the Gospel) apostolic constitution almighty God apostolic exhortation (by a pope) beatific vision Apostolic Fathers Beatitudes, the Apostolic See Being (God) appendixes Beloved Apostle, the archabbot Beloved Disciple, the archangel Michael, the Benediction of the Blessed Sacrament archdiocese Benedictus Archdiocese of Seattle berakah (pl.: -

Appendix B: Baptismal Churches Eastern Rite Churches in Communion with Rome Eastern Rite Churches Not in Communion with Rome

Appendix B: Baptismal Churches Eastern Rite Churches in Communion with Rome The Churches on this list are Catholic Churches. The Roman Catholic Church recognizes fully the sacraments that have already been received. There can be no doubt cast upon the validity of Baptism and Confirmation conferred in the Eastern Churches. It is sufficient to establish the fact that Baptism was administered. Valid Confirmation (chrismation) is always administered at the same time as Baptism. In some situations, the child has also received First Communion at the time of Baptism. Children who have celebrated the full initiation rite in the Eastern Rite Church may require further catechesis concerning the sacrament of the Eucharist. If the child is attending a Roman Catholic school the ongoing Religious Education program will provide this catechesis. If it is deemed appropriate the family may be encouraged to complete a family resource book at home and to continue the practice of bringing their child to the table of the Lord. Adults who have celebrated the full initiation rite in the Eastern Rite Church are to be catechized as needed. No rite is required. The Eastern Churches in Communion with Rome, as listed in the Archdiocese of Toronto’s Directory include: Alexandrian Rite Byzantine Rite Coptic Catholic Church Melkite Catholic Church Ethiopian Catholic Church Byzantine Slovak Catholic Church Byzantine Ukrainian Catholic Church Antiochene Rite (West Syrian) Albanian Catholic Church Malankara (Malankarese) Catholic Church Byelorussian Catholic Church Maronite -

View of the Project…………………………………………

PARTING OF THE WATERS: DIVERGENCES IN EARLY THEOLOGIES OF BAPTISMAL ANOINTING PRACTICES Thesis Submitted to The College of Arts and Sciences of the UNIVERSITY OF DAYTON In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for The Degree of Master of Arts in Theological Studies By Elizabeth H. Farnsworth Dayton, Ohio May 2013 PARTING OF THE WATERS: DIVERGENCES IN EARLY THEOLOGIES OF BAPTISMAL ANOINTING PRACTICES Name: Farnsworth, Elizabeth H. APPROVED BY: ________________________________ Fr. Silviu N. Bunta, Ph.D. Faculty Advisor ________________________________ Matthew Levering, Ph.D. Faculty Reader ________________________________ William Johnston, Ph.D. Faculty Reader ii ABSTRACT PARTING OF THE WATERS: DIVERGENCES IN EARLY THEOLOGIES OF BAPTISMAL ANOINTING PRACTICES Name: Farnsworth, Elizabeth H. University of Dayton Advisor: Fr. Silviu Bunta, Ph.D. The practice of baptismal anointing was diverse both in practice and interpretation in the first four centuries. Early Christians at times interpreted the practice of baptismal anointing in the context of Old Testament anointings, as well as the baptism of Jesus in the Jordan. Liturgical development of baptism can be seen as early as the second and third centuries with relation to anointing practices. The fourth century shows further liturgical development affected by the Christological and Pneumatological debates, as well as the growth of Christianity both doctrinally and ecclesially. As a result of the heresy debates of the fourth century, many early Christians sought to unify the practice and doctrinal theology concerning the baptismal practices. An understanding of the ritual development can aid in modern theological discussions concerning the baptismal liturgy. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT………………………………………………………………………...……iii I. INTRODUCTION…………………………………………………………..………..…1 Overview of the Project…………………………………………......………….…4 II. -

Abbreviated Chicago Style Booklet

An ABBREVIATED GUIDE to Chicago and Religion & Literature Style Prepared by Katie Bascom and Vienna Wagner 2015 A Note on this Guide Here you’ll find helpful excerpts from The Chicago Manual of Style as well as discussion of the Religion & Literature House Style sheet, which should provide the necessary foundation to begin editorial work on the journal. While you’ll, no doubt, find it necessary to frequently consult the online style guide, this abbreviation covers some of the problem areas for those new to Chicago style and the R&L style sheet. Though The Chicago Manual of Style includes treatments of general usage issues, its citation and documentation system proves most daunting to new editors. Further, Religion & Literature modifies Chicago documentation practices with an eye toward brevity, concision, and aesthetic appeal. Consequently, this guide devotes most of its attention to practices such as the shortened endnote plus bibliography citation style. In general, Chicago style considers the documentation of material cited in-text the primary function of the endnote system because endnotes can provide documentation without interfering with the reading experience. Therefore, Chicago discourages discursive endnotes. Every system has its drawbacks, of course, but, properly executed, the Chicago/R&L style creates clean, well-documented essays free from cumbersome in-text apparatus. Basically, the reader shouldn’t need to read the endnotes unless the reader needs to track down the sources, and the citation system makes it clear, early on, that little more than such information will be found there. In addition to the endnote/bibliography citation style, Chicago downstyle consistently proves confusing to new editors. -

Living Languages in Catholic Worship; an Historical Inquiry

RIL KOROLEVSKY iraiBE LANGUAGES IN CATHOLIC WORSHIP historical Inquiry D ATTWATE-R LONGMANS — ^.^...^ i.uiiu, inuiuumg spuKen are , used in the public worship Church of Rome, even if only by inorities. The contemporary and movement among Catholics for a use of the mother tongue in 1 worship now gives these minori- ipecial interest and importance, ok is not a plea for such use it is plain where the author's lies) y : what it offers is a brief storical examination of liturgical in the Eastern and Western parts hurch from the earliest times to nt day. Father Cyril Korolevsky, priest of the Byzantine rite and the 8 Liturgy in Greek, Slavonic, n or Arabic as required, is an :>nsultant in Rome and he has personal part in some of the ents he describes. His book, i its origin in a report prepared r the use of the Holy See in 1929, f interesting and little-known iring on a question of the greatest nportance. LIVING LANGUAGES IN CATHOLIC WORSHIP LIVING LANGUAGES IN CATHOLIC WORSHIP An Historical Inquiry by CYRIL KOROLEVSKY Priest of the Byzantine rite. Consultant at Rome ofthe Sacred Eastern Congrega- tion, of the Commission for Eastern Liturgy and of the Commission for the Codification of Eastern Canon Law Translated by DONALD ATTWATER LONGMANS, GREEN AND CO LONDON • NEW YORK • TORONTO LONGMANS, GREEN AND CO LTD 6 & 7 CLIFFORD STREET LONDON W I THIBAULT HOUSE THIBAULT SQUARE CAPB TOWN 605-6II LONSDALE STREET MELBOURNE C I LONGMANS, GREEN AND CO INC 55 FIFTH AVENUE NEW YORK 3 LONGMANS, GREEN AND CO 20 CRANFIELD ROAD TORONTO l6 ORIENT LONGMANS PRIVATE LTD CALCUTTA BOMBAY MADRAS DELHI HYDERABAD DACCA First published in France under the title "Liturgie en Langue Vivante" by Editions du Cerf: Paris 195s First published in Great Britain . -

Sacred Words and Music an Absurdly Brief Dash Through the History of Church Music

Sacred Words and Music An absurdly brief dash through the history of church music Prepared for the exclusive enjoyment of those who attend the Sunday Adult Forum The Honorable Tricia Herban, Presiding (Offered in spite of the goodly advice of Sara Seidel, Director of Music) St. John’s Episcopal Church, Worthington, Ohio Sunday December 10, 2017 Focus is (mostly) on England ➢ Plainchant to Polyphony (10 mins) ➢ Impact of the Reformation (10 mins) ➢ The English Christmas Carol (10 mins) Liturgy & Chant ▪ Liturgy is comprised of the texts (and actions) in a worship service ▪ Chanting is the speaking of the liturgy in a series of tones in fairly close consecutive pitches. No other pitches, no harmony. A plain song. [Chanting’s roots are in Jewish traditions of song (esp. the Psalms) and worship.] Testamentum Eternum Cistercian Link In the Beginning, there were only words Early Christians were, for the most part, converted Jews. As such, their traditions included chanting as an integral part of public worship. As Christian liturgies evolved, chanting was a given. And yet, at the time there was no means of indicating the desired tone, no means of indicating changes in tone, no way to convey rhythm, no way to preserve and replicate how the liturgy should sound – except to learn by imitation. Common Liturgy & Chant Pope Gregory (590-604) called for a common liturgy in order to consolidate as many regional variants as possible. Several sorts of chant had also developed – but most eventually gave way to the Gregorian Chant which peaked around 1100. The Sarum Use chant was used in England until the Reformation. -

FEAST of ALL SAINTS . Ar-R

Feast of All Saints 307 37 lgn CK, 246. 38 Nilles, I, 481. 3s P.F., Benad. Semi,rutm et Segotunt in Festo Natioi,tatis B.M.V. aoFranz, I, 370. a1 Geramb, 175f. 42WH, 112f.; Geramb, 158ff. CTIAPTER 26 All Sai,nts and All Souls FEAST OF ALL SAINTS . Ar-r. Menrrns.The Church of Antioch kept a commemoration of all holy martyrs on the first Sunday after Pentecost. Saint john Chrysostom, who served as preacher at Antioch before he became patriarch of Constantinople, delivered annual sermons on the occasion of this festival. They were entitled "Praise of All the Holy Martyrs of the Entire World." 1 In the course of the succeeding centuries the feast spread through the whole Eastern Church and, by the seventh century, was everywhere kept as a public holyday. In the West the Feast of All Holy Martyrs was introduced when Pope Boniface IV (615) was given the ancient Roman ternple of the Pantheon by Emperor Phocas (610) and dedicated it as a church to the Blessed Virgin Mary and all the martyrs. The date of this dedication was May 13, and on this date the feast was then annually held in Rome.2 Two hundred years later Pope Gregory IV (S a) transferred the celebration to November 1. The reason for this transfer is quite interesting, especially since some scholars have claimed that the Church assigned All Saints to November I in order to substitute a feast of Christian signiff- cance for the pagan Germanic celebrations of the demon cult at that time of the year.3 Actually, the reason for the transfer was that the many pilgrims who came to Rome for the Feast of the 30B ,4Il Saints and All Souls Pantheon could be fed more easily after the harvest than in the spring.l Ar-r, SerNrs ' Meanwhile, the practice had spread of including in this memorial not only all martyrs, but the other saints as well' Pope Gregory lll (741) had already stated this when he dedi- cai"d a chapel in St. -

Definition of Liturgy

Definition of Liturgy (From the Catholic Encyclopedia) Liturgy (leitourgia) is a Greek composite word meaning originally a public duty, a service to the state undertaken by a citizen. Its elements are leitos (from leos = laos, people) meaning public, and ergo (obsolete in the present stem, used in future erxo, etc.), to do. From this we have leitourgos, "a man who performs a public duty", "a public servant", often used as equivalent to the Roman lictor; then leitourgeo, "to do such a duty", leitourgema, its performance, and leitourgia, the public duty itself. At Athens the leitourgia was the public service performed by the wealthier citizens at their own expense, such as the office of gymnasiarch, who superintended the gymnasium, that of choregus, who paid the singers of a chorus in the theatre, that of the hestiator, who gave a banquet to his tribe, of the trierarchus, who provided a warship for the state. The meaning of the word liturgy is then extended to cover any general service of a public kind. In the Septuagint it (and the verb leitourgeo) is used for the public service of the temple (e.g., Exodus 38:27; 39:12, etc.). Thence it comes to have a religious sense as the function of the priests, the ritual service of the temple (e.g., Joel 1:9, 2:17, etc.). In the New Testament this religious meaning has become definitely established. In Luke 1:23, Zachary goes home when "the days of his liturgy" (ai hemerai tes leitourgias autou) are over. In Hebrews 8:6, the high priest of the New Law "has obtained a better liturgy", that is a better kind of public religious service than that of the Temple.