Reporter As Citizen: Newspaper Ethics and Constitutional Values

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Confronting Supreme Court Fact Finding Allison Orr Larsen William & Mary Law School, [email protected]

College of William & Mary Law School William & Mary Law School Scholarship Repository Faculty Publications Faculty and Deans 2012 Confronting Supreme Court Fact Finding Allison Orr Larsen William & Mary Law School, [email protected] Repository Citation Larsen, Allison Orr, "Confronting Supreme Court Fact Finding" (2012). Faculty Publications. 1284. https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/facpubs/1284 Copyright c 2012 by the authors. This article is brought to you by the William & Mary Law School Scholarship Repository. https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/facpubs CONFRONTING SUPREME COURT FACT FINDING Allison Orr Larsen* I. PREVALENCE OF IN-HOUSE FACT FINDING AT THE SUPREME COURT ....................................................................... 1264 A. Defining the Terms and the Quest...................................... 1264 B. How Common Is Modern In-House Fact Finding?......... 1271 II. A TAXONOMY OF IN-HOUSE FACT FINDING........................... 1277 A. What Factual Assertions Are Supported By Authorities Found “In House?”............................................................. 1278 1. Subject Matter of Facts Found In House..................... 1278 2. How Do the Justices Use In-House Factual Research? ....................................................................... 1280 B. Where Do the Sources Come From? ................................. 1286 III. WHY THE CURRENT PROCEDURAL APPROACH IS OUTDATED: RISKS OF MODERN IN-HOUSE FACT FINDING ............................................................................ 1290 A. Systematic -

U.S. Supreme Court Justices and Press Access

BYU Law Review Volume 2012 Issue 6 Article 4 12-18-2012 U.S. Supreme Court Justices and Press Access RonNell Andersen Jones Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.byu.edu/lawreview Part of the Courts Commons, Journalism Studies Commons, and the Mass Communication Commons Recommended Citation RonNell Andersen Jones, ��.��. �������������� ���������� ���������������� ������ ���������� ������������, 2012 BYU L. Rᴇᴠ. 1791. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Brigham Young University Law Review at BYU Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in BYU Law Review by an authorized editor of BYU Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. U.S. Supreme Court Justices and Press Access RonNell Andersen Jones * I. INTRODUCTION Scholars and commentators have long noted the strained relationship between the United States Supreme Court and the media that wishes to report upon its work. 1 The press corps complains that the Court is cloistered, elitist, and unbending in its traditions of isolation from the public.2 Critics regularly assert that, especially when cases of major significance to many Americans are being argued, 3 the Court * Associate Professor of Law, J. Reuben Clark Law School, Brigham Young University. The author thanks student researchers Brooke Nelson Edwards, Joe Orien, and Brody Wight for their assistance. I. Linda Greenhouse, Thinking About the Supreme Court After Bush v. Gore, 35 IND. L. REV. 435, 440 (2002) (calling the relationship "problematic at best"); Linda Greenhouse, Telling the Court's Story: Justice and Journalism at the Supreme Court, 105 YALE L.J. 1537, 1559 (1996) (describing the Court as "quite blithely oblivious to the needs of those who convey its work to the outside world"); Paul W. -

Televising Supreme Court and Other Federal Court Proceedings: Legislation and Issues

Order Code RL33706 CRS Report for Congress Received through the CRS Web Televising Supreme Court and Other Federal Court Proceedings: Legislation and Issues Updated November 8, 2006 Lorraine H. Tong Analyst in American National Government Government and Finance Division Congressional Research Service ˜ The Library of Congress Televising Supreme Court and Other Federal Court Proceedings: Legislation and Issues Summary Over the years, some in Congress, the public, and the media have expressed interest in television or other electronic media coverage of Supreme Court and other federal court proceedings. The Supreme Court has never allowed live electronic media coverage of its proceedings, but the Court posts opinions and transcripts of oral arguments on its website. The public has access to audiotapes of the oral arguments and opinions that the Court gives to the National Archives and Records Administration. Currently, Rule 53 of the Federal Rules of Criminal Procedure prohibits the photographing or broadcasting of judicial proceedings in criminal cases in federal courts. The Judicial Conference of the United States prohibits the televising, recording, and broadcasting of district trial (civil and criminal) court proceedings. Under conference policy, each court of appeals may permit television and other electronic media coverage of its proceedings. Only two of the 13 courts of appeals, the Second and Ninth Circuit Courts of Appeals, have chosen to do so. Although legislation to allow camera coverage of the Supreme Court and other federal court proceedings has been introduced in the current and previous Congresses, none has been enacted. In the 109th Congress, four bills have been introduced — H.R. 2422, H.R. -

Volume 10 2004

Legal Writing The Journal of the Legal Writing Institute Volume 10 2004 The Golden Pen Award Third Golden Pen Award ......................................... Joseph Kimble ix Presentation of the Golden Pen Award Lessons Learned from Linda Greenhouse .... Steven J. Johansen xi Remarks – On Receiving the Golden Pen Award ......................................... Linda Greenhouse xv 2003 AALS Annual Meeting Discussion: Better Writing, Better Thinking: Introduction ...... Jo Anne Durako 3 Better Writing, Better Thinking: Thinking Like a Lawyer ....................................... Judith Wegner 9 Better Writing, Better Thinking: Using Legal Writing Pedagogy in the “Casebook” Classroom (without Grading Papers) ............................................. Mary Beth Beazley 23 Better Writing, Better Thinking: Concluding Thoughts ................................................................. Kent Syverud 83 Articles Composition, Law, and ADR .......................... Anne Ruggles Gere Lindsay Ellis 91 The Use and Effects of Student Ratings in Legal Writing Courses: A Plea for Holistic Evaluation of Teaching ................................... Judith D. Fischer 111 iii 200 4] Volume 10 Table of Contents [10 Integrating Technology: Teaching Students to Communicate in Another Medium ............ Pamela Lysaght Danielle Istl 163 Linking Technology to Pedagogy in an Online Writing Center .................................... Susan R. Dailey 181 2003 AALS Annual Meeting Panel Discussion: “The Law Professor as Legal Commentator” ........................ -

Reese, Stephen D., the Structure of News Sources on Television: A

Reese, Stephen D., The structure of news sources on television: A network analysis of 'CBS News,' 'Nightline,' 'MacNeil/Lehrer,' and 'This Week with David Brinkley' , Journal of Communication, 44:2 (1994:Spring) p.84 Reese, Stephen D., The structure of news sources on television: A network analysis of 'CBS News,' 'Nightline,' 'MacNeil/Lehrer,' and 'This Week with David Brinkley' , Journal of Communication, 44:2 (1994:Spring) p.84 Reese, Stephen D., The structure of news sources on television: A network analysis of 'CBS News,' 'Nightline,' 'MacNeil/Lehrer,' and 'This Week with David Brinkley' , Journal of Communication, 44:2 (1994:Spring) p.84 Reese, Stephen D., The structure of news sources on television: A network analysis of 'CBS News,' 'Nightline,' 'MacNeil/Lehrer,' and 'This Week with David Brinkley' , Journal of Communication, 44:2 (1994:Spring) p.84 Reese, Stephen D., The structure of news sources on television: A network analysis of 'CBS News,' 'Nightline,' 'MacNeil/Lehrer,' and 'This Week with David Brinkley' , Journal of Communication, 44:2 (1994:Spring) p.84 Reese, Stephen D., The structure of news sources on television: A network analysis of 'CBS News,' 'Nightline,' 'MacNeil/Lehrer,' and 'This Week with David Brinkley' , Journal of Communication, 44:2 (1994:Spring) p.84 Reese, Stephen D., The structure of news sources on television: A network analysis of 'CBS News,' 'Nightline,' 'MacNeil/Lehrer,' and 'This Week with David Brinkley' , Journal of Communication, 44:2 (1994:Spring) p.84 Reese, Stephen D., The structure of news sources -

Hawaiian Day July 7

Full Moon Day July 5 According toThe Old Farmer's Almanac, July's full moon is known as the Full Buck Moon. That's because it's normally the month when a buck deer gets the beginnings of his new antlers. It's also known as the Thunder Moon (because thunderstorms are common at this time) and the Full Hay Moon. Do you know the Names of All the Full Moons? How many "moon" phrases you name? The moon phase is the shape of the directly sunlit portion of the Moon as viewed from Earth. The phases gradually change over the period of a synodic month, as the orbital positions of the Moon around Earth and of Earth around the Sun Shift. July 6 Fried Chicken Day Fried chicken has a long and interesting history—Here are a few facts: Fried Chicken Was Invented by the Scottish. Before WWII, It Was a Special Occasion Dish. Not all Chickens are Suitable for Frying. There are Three Primary Frying Methods— deep-frying ,pressure- frying (or “broasting”), cast-iron skillet . The Pressure Fryer Was the Secret to KFC’s Success. Hawaiian Day July 7 The Hawaiian Islands Kingdom was annexed by the United States on this day in 1898. Hawaii was once an independent kingdom. (1810 - 1893) The flag was designed at the request of King Kamehameha I. It has eight stripes of white, red and blue that represent the eight main islands. The flag of Great Britain is emblazoned in the upper left corner to honor Hawaii's friendship with the British. -

Views Expressed Are Those of the Cambridge Ma 02142

Cover_Sp2010 3/17/2010 11:30 AM Page 1 Dædalus coming up in Dædalus: the challenges of Bruce Western, Glenn Loury, Lawrence D. Bobo, Marie Gottschalk, Dædalus mass incarceration Jonathan Simon, Robert J. Sampson, Robert Weisberg, Joan Petersilia, Nicola Lacey, Candace Kruttschnitt, Loïc Wacquant, Mark Kleiman, Jeffrey Fagan, and others Journal of the American Academy of Arts & Sciences Spring 2010 the economy Robert M. Solow, Benjamin M. Friedman, Lucian A. Bebchuk, Luigi Zingales, Edward Glaeser, Charles Goodhart, Barry Eichengreen, of news Spring 2010: on the future Thomas Romer, Peter Temin, Jeremy Stein, Robert E. Hall, and others on the Loren Ghiglione Introduction 5 future Herbert J. Gans News & the news media in the digital age: the meaning of Gerald Early, Henry Louis Gates, Jr., Glenda R. Carpio, David A. of news implications for democracy 8 minority/majority Hollinger, Jeffrey B. Ferguson, Hua Hsu, Daniel Geary, Lawrence Kathleen Hall Jamieson Are there lessons for the future of news from Jackson, Farah Grif½n, Korina Jocson, Eric Sundquist, Waldo Martin, & Jeffrey A. Gottfried the 2008 presidential campaign? 18 Werner Sollors, James Alan McPherson, Robert O’Meally, Jeffrey B. Robert H. Giles New economic models for U.S. journalism 26 Perry, Clarence Walker, Wilson Jeremiah Moses, Tommie Shelby, and others Jill Abramson Sustaining quality journalism 39 Brant Houston The future of investigative journalism 45 Donald Kennedy The future of science news 57 race, inequality Lawrence D. Bobo, William Julius Wilson, Michael Klarman, Rogers Ethan Zuckerman International reporting in the age of & culture Smith, Douglas Massey, Jennifer Hochschild, Bruce Western, Martha participatory media 66 Biondi, Roland Fryer, Cathy Cohen, James Heckman, Taeku Lee, Pap Ndiaye, Marcyliena Morgan, Richard Nisbett, Jennifer Richeson, Mitchell Stephens The case for wisdom journalism–and for journalists surrendering the pursuit Daniel Sabbagh, Alford Young, Roger Waldinger, and others of news 76 Jane B. -

Oral History Interview with Sharon Huntley Kahn, July 10, 2018

Archives and Special Collections Mansfield Library, University of Montana Missoula MT 59812-9936 Email: [email protected] Telephone: (406) 243-2053 This transcript represents the nearly verbatim record of an unrehearsed interview. Please bear in mind that you are reading the spoken word rather than the written word. Oral History Number: 463-001 Interviewee: Sharon Huntley Kahn Interviewer: Donna McCrea Date of Interview: July 10, 2018 Donna McCrea: This is Donna McCrea, Head of Archives and Special Collections at the University of Montana. Today is July 10th of 2018. Today I'm interviewing Sharon Huntley Kahn about her father Chet Huntley. I'll note that the focus of the interview will really be on things that you know about Chet Huntley that other people would maybe not have known: things that have not been made public already or don't appear in many of the biographical materials and articles about him. Also, I'm hoping that you'll share some stories that you have about him and his life. So I'm going to begin by saying I know that you grew up in Los Angeles. Can you maybe start there and talk about your memories about your father and your time in L.A.? Sharon Kahn: Yes, Donna. Before we begin, I just want to say how nice it is to work with you. From the beginning our first phone conversations, I think at least a year and a half ago, you've always been so welcoming and interested, and it's wonderful to be here and I'm really happy to share inside stories with you. -

From Making What's in 1951, He Recalls Having Only 14 on His Staff: Douglas Edwards (Who Had Been Anchoring and Coproducing a 15- Minute Yours Theirs

matter of fact, the censorship has been fast Four years later, Mr. Edwards was back in view of ratings and critics' notices -but and reasonably intelligent .... at the conventions, this time to co- anchor when CBS remained second to NBC with "You get accustomed to these long -dis- some of the sessions with Walter the new team, Mr. Cronkite was brought tance conversations after a few years, but Cronkite. By then the capability of going back as "national editor" on the 1964 that first two -way with the beachhead pro- to the floor was developed and, as Mr. Ed- election night. duced a pleasant thrill. I gave [Bill] Downs wards says, "Television was less the tail From 1951, CBS did have its the go- ahead. Twenty seconds later, the being wagged by the dog; it may have been "showpiece," as Mr. Mickelson calls it- bottom fell out of the circuit and he the power." See It Now with Edward R. Murrow as became unintelligible. That's the way it Mr. Cronkite, who had been brought in host and coproducer with Fred Friendly goes. from wTOPTv Washington by Mr. (who later rose to the CBS News presiden- "Over the far shore the boys stumble Mickelson, anchored every convention cy). The program represented a move out through the dark to reach their and election night coverage from that time of the "newsreel" era. Among the show's camouflaged transmitters. They speak with the exception of 1964 when Robert innovations for television: it was the first their stories. Sometimes they get through Trout (who'd handled conventions pre- to shoot its own film and use a sound track and sometimes they don't." viously for CBS Radio) and Roger Mudd without dubbing, as well as the first to After the war, Mr. -

" WE CAN NOW PROJECT..." ELECTION NIGHT in AMERICA By. Sean P Mccracken "CBS NEWS Now Projects...NBC NEWS Is Read

" WE CAN NOW PROJECT..." ELECTION NIGHT IN AMERICA By. Sean P McCracken "CBS NEWS now projects...NBC NEWS is ready to declare ...ABC NEWS is now making a call in....CNN now estimates...declares...projects....calls...predicts...retracts..." We hear these few opening words and wait on the edges of our seats as the names and places which follow these familiar predicates make very well be those which tell us in the United States who will occupy the White House for the next four years. We hear the words, follow the talking-heads and read the ever changing scripts which scroll, flash or blink across our television screens. It is a ritual that has been repeated an-masse every four years since 1952...and for a select few, 1948. Since its earliest days, television has had a love affair with politics, albeit sometimes a strained one. From the first primitive experiments at the Republican National Convention in 1940, to the multi angled, figure laden, information over-loaded spectacles of today, the "happening" that unfolds every four years on the second Tuesday in November, known as "Election Night" still holds a special place in either our heart...or guts. Somehow, it still manages to keep us glued to our television for hours on end. This one night that rolls around every four years has "grown up" with many of us over the last 64 years. Staring off as little more than chalk boards, name plates and radio announcers plopped in front of large, monochromatic cameras that barely sent signals beyond the limits of New York City and gradually morphing into color-laden, graphic-filled, information packed, multi channel marathons that can be seen by virtually...and virtually seen by...almost any human on the planet. -

2002 Conference Program Book

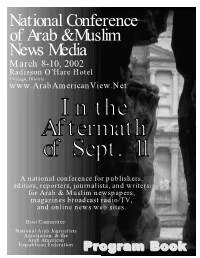

National Conference of Arab & Muslim News Media March 8-10, 2002 Radisson O’Hare Hotel Chicago, Illinois www.ArabAmericanView.Net In the Aftermath of Sept. 11 A national conference for publishers, editors, reporters, journalists, and writers for Arab & Muslim newspapers, magazines broadcast radio/TV, and online news web sites. Host Committee: National Arab Journalists Association, & the Arab American Republican Federation PPrrooggrraamm BBooookk TheThe NationalNational ArabArab && MuslimMuslim JournalismJournalism ConferenceConference is co-hosted by the Arab American View Newspaper the National Arab Journalists Association & the Arab American Republican Federation which promotes Arab American involvement in the American political process. for more information, visit www.ArabAmericanView.net PO Box 2127, Orland Park, IL 60462 708-403-3380 fax [email protected] Page -2- t is my pleasure This success would not have been I to welcome you without the hard work and dedication of to this event men and women of our community like and thank you for you. your attendance We of the Arab American and support. Republican Federation dedicate this event It is a time to you all. when our commu- Be proud that you are an Arab nity is under siege American. and pressure from WE WILL NOT YIELD TO PRESSURE all sides that your OR INTIMIDATION BUT STAND TALL. support gives it the strength it needs. -Dr. Shibli M. Sawalha, Your participation is the more Chairman Arab American important because it points to the Republican Federation resiliency of our community and our Committeeman, Homer Township resolve to defend it and be involved in Republican Organization the civil process of our country. -

Ray Hanania USG Publishing, President

"Writing in the Next Millennium" Final The 1999 National Professional Literary Conference on Arab American and Ethnic Writing The 1999 QALAM Award for Arab American Writing in Poetry, Fiction & Non-Fiction The 1999 M.T. Mehdi Courage in Writing Awards October 8, 9, 10, 1999 Chicago, Illinois Days Inn O’Hare South 3801 S. Mannheim Road, Schiller Park, Illinois Sponsored by USG Publishing & Hanania Enterprises Ltd. • The QALAM Writing Awards (“Quest for Arab-American Literature of Accomplishment and Merit” ) is Organized by Lisa Suhair Majaj and sponsored by MIZNA, Jusoor, Al-Jadid literary publications, and also the AAUG. The conference is also pleased to have the support and sponsorship of Arab Film Distribution, the United Holy Land Fund, The Arab Star Newspaper, and all of the speakers and participants attending this conference. Ahlan wa Sahlan … Welcome to Chicago and the First Annual National Professional Literary Conference on Arab American and Ethnic Writing. This 1999 conference features dozens of professional writers who are here to share their experiences with you, to help all of us improve our networking, and to also encourage all of us to seek to improve our writings and become more successful. This conference also features two exciting events: The first is the 1999 QALAM Award in Writing contest. The contest name, QALAM, is suggested by Lisa Suhair Majaj, who worked hard to organize this first contest and who is responsible for making it a success. It stands for Quest for Arab-American Literature of Accomplishment and Merit (themed by Mohja Kahf). It goes without saying that without Lisa’s help, this First Annual event which is intended to showcase the best entries of writing from our community might not have taken place.