TOCC0599DIGIBKLT.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Register of Music Performed in Concert, Nazareth, Pennsylvania from 1796 to 1845: an Annotated Edition of an American Moravian Document

A register of music performed in concert, Nazareth, Pennsylvania from 1796 to 1845: an annotated edition of an American Moravian document Item Type text; Thesis-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Strauss, Barbara Jo, 1947- Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 10/10/2021 23:14:00 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/347995 A REGISTER OF MUSIC PERFORMED IN CONCERT, NAZARETH., PENNSYLVANIA FROM 1796 TO 181+52 AN ANNOTATED EDITION OF AN AMERICAN.MORAVIAN DOCUMENT by Barbara Jo Strauss A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the SCHOOL OF MUSIC In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF MUSIC WITH A MAJOR IN MUSIC HISTORY In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 1 9 7 6 Copyright 1976 Barbara Jo Strauss STATEMENT BY AUTHOR This thesis has been submitted in partial fulfill ment of requirements for an advanced degree at The Univer sity of Arizona and is deposited in the University Library to be made available to borrowers under rules of the Library. Brief quotations from this thesis are allowable without special permission, provided that accurate ac knowledgment of source is made. Requests for permission for extended quotation from or reproduction of this manu script in whole or in part may -

Joseph Woelfl Streichquartette Op. 4 Und Op. 10

Joseph Woelfl Streichquartette Op. 4 und Op. 10 Quatuor Mosaïques Erich Höbarth und Andrea Bischof, Violine Anita Mitterer, Viola Christophe Coin, Violoncello paladino music Quatuor Mosaïques Erich Höbarth und/and Andrea Bischof Violinen, Franz Geissenhof, Wien 1806, Inv.-Nrr. SAM 683 und 684 Violins, Franz Geissenhof, Vienna 1806, Inv.-No. SAM 683 and 684 Anita Mitterer Abb. auf S. 1: Viola, Franz Geissenhof, Violine, Franz Geissenhof, Wien 1806, Wien 1797, Inv.-Nr. SAM 683 Inv.-Nr. SAM 685 Ill. on p. 1: Viola, Franz Geissenhof, Violin, Franz Geissenhof, Vienna 1806, Vienna 1797, Inv.-No. SAM 683 Inv.-No. SAM 685 Christophe Coin Violoncello, Franz Geissenhof, Wien 1794, Inv.-Nr. SAM 686 Violoncello, Franz Geissenhof, Vienna 1794, Inv.-No. SAM 686 Deutsch: Seite Franz Geissenhofs Instrumente 4 Joseph Woelfl 7 English: page Franz Geissenhof‘s instruments 12 Joseph Woelfl 15 2 FRANZ GEISSENHOFS INSTRUMENTE Joseph Woelfl (1773 –1812) Streichquartett Op. 4 Nr. 3, c-Moll 01 Allegro 7'46 02 Menuetto (Allegretto) 4'37 03 Adagio ma non troppo 7'35 04 Finale (Presto) 5'57 Streichquartett Op. 10 Nr. 4, G-Dur 05 Allegro 7'24 06 Menuetto (Allegro) 3'41 07 Andante 5'10 08 Prestissimo 4'16 Streichquartett Op. 10 Nr. 1, C-Dur 09 Allegro moderato 7'35 10 Andante 8'11 11 Menuetto (Allegro) 4'05 12 Allegro 5'26 Gesamtspielzeit / total duration: 74'00 3 FRANZ GEISSENHOFS INSTRUMENTE Druckzettel von Franz Geissenhofs Violine von 1806 Inv.-Nr. SAM 683 Franz Geissenhof war der einflussreichste Geigenbauer zur Zeit der Wiener Klassik. Völlig zu Recht wurde er bereits kurz nach seinem Tod mit dem Beinamen eines „Wiener Stradivari“ Printed label of Franz Geissenhof’s violin bedacht, was nicht nur als eine schmeichelhafte Anspielung auf seine handwerklichen Fähig- from 1806 Inv.-No. -

Sacred Space and Sublime Sacramental Piety the Devotion of the Forty Hours and W.A

Sacred Space and Sublime Sacramental Piety The Devotion of the Forty Hours and W.A. Mozart's Two Sacramental Litanies (Salzburg 1772 and 1776) Petersen, Nils Holger Published in: Heterotopos Publication date: 2012 Document version Early version, also known as pre-print Citation for published version (APA): Petersen, N. H. (2012). Sacred Space and Sublime Sacramental Piety: The Devotion of the Forty Hours and W.A. Mozart's Two Sacramental Litanies (Salzburg 1772 and 1776). In D. M. Colceriu (Ed.), Heterotopos: Espaces sacrés (Vol. I, pp. 171-211). Editura Universitatii din Bucuresti. Download date: 28. sep.. 2021 Sacred Space and Sublime Sacramental Piety: The Devotion of the Forty Hours and W.A. Mozart’s two Sacramental Litanies (Salzburg 1772 and 1776) Nils Holger Petersen, University of Copenhagen * In this article, I shall discuss the musical response of the young W.A. Mozart (1756−91) to notions of sacredness in connection with Eucharistic piety of the late eighteenth century at the Cathedral of Salzburg, with which he was unofficially associated since early childhood through his father Leopold Mozart (1719−87) who was employed by the archbishop of Salzburg and where Wolfgang himself also became officially employed in the summer of 1772. Eucharistic piety, of course, was a general phenomenon in the Latin Roman Church as a consequence of the developments in Eucharistic thought especially since the eleventh century where the foundations for the later doctrine of the transubstantiation (formally confirmed at the fourth Lateran Council in 1215) were laid leading to new forms of pious practices connected to the Eucharistic elements, not least the establishing of the Feast of Corpus Christi (gradually from a slow start in the thirteenth century). -

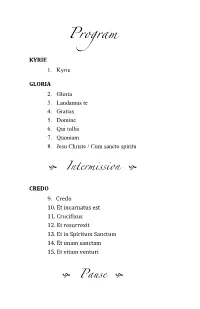

Program KYRIE 1

Program KYRIE 1. Kyrie GLORIA 2. Gloria 3. Laudamus te 4. Gratias 5. Domine 6. Qui tollis 7. Quoniam 8. Jesu Christe / Cum sancto spiritu h h Intermission CREDO 9. Credo 10. Et incarnatus est 11. Crucifixus 12. Et resurrexit 13. Et in Spiritum Sanctum 14. Et unam sanctam 15. Et vitam venturi h h Pause Program Notes SANCTUS Requiem While many people are familiar with the story of Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart’s , K. 626, which was Mass left in C unfinished minor upon Mozart’s death, far fewer people are aware that Mozart left an even more Requiem BENEDICTUS16. Sanctus ambitious vocal work, the “Great” , K. 427 (K. 417a), incomplete as well. If the tale of the Mass in C is minor the basis of great drama—as demonstrated in the 1984 Academy Award-winning flm 17. Benedictus Amadeus—then the mystery of the is its musical AGNUS DEI equivalent. After two hundred years of sleuthing and speculation, it remains unclear why Mozart composed the mass, as well as why he never comple ted it. 18. Agnus Dei Although Mozart had written a number of masses while employed by 19. Dona nobis pacem the Prince Archbishop of Salzburg, Hieronymus von Colloredo, he was Mass in C minor hh gone from the prince’s court for over a year when he began to compose the in the summer of 1782. Mozart’s single piece of correspondence concerning the mass only adds to the mystery. In a letter dated January 14, 1783, to his father Leopold, Mozart wrote elliptically that “the score of half of a mass, which is still lying here waiting to be finished, is the best proof that I really made the promise.” While the promise Mozart alluded to in the letter has traditionally been interpreted as an olive branch to his father, who had not approved of Mozart’s recent marriage, or as an ode of thanksgiving to his wife Constanze, recent research hints that Mozart had promised his father that he would reconcile with Archbishop Colloredo. -

574163 Itunes Haydn

Michael HAYDN Missa Sancti Nicolai Tolentini Vesperae Pro Festo Sancti Innocentium Anima Nostra Harper • Owen • Charlston Marko Sever, Organ Lawes Baroque Players St Albans Cathedral Girls Choir Tom Winpenny 1 46 8 ! @ $ & ) ¡ Michael Jenni Ha2rpe46r –80–@ $ –& ) –¡ , Emily Owen – – – – $, S&o ) pr¡ano H(1A73Y7–1D806N ) Helen Charlston, Mezzo-soprano – Missa Sancti Nicolai Tolentini, MH 109 (1768) 36:40 Marko Sever, Organ (Text: Latin Mass) 1 Kyrie eleison 3:31 1 @L $ aw*e s) B¡aroque Players1 @ $ * ) ¡ 2 Kati Debretzeni – – , Miles Golding – – , Violin 3 Gloria in excelsis Deo 3:16 1 @ $ ¡ Henrik Persson, Cello – – 4 Qui tollis 2:27 1 @ $ * ) ¡ – – 5 Quoniam 2:37 Peter McCarthy, Double bass 1 25 6 8 @ 6 Cum Sancto Spiritu 2:15 Thomas Hewitt, Ellie Lovegrove, Trumpet – – – 7 Credo in unum Deum 2:22 1 35 6 8 0 @ ¡ 8 Et incarnatus est 2:51 St Albans Cathedral Girls Choir – – – – Et resurrexit 4:49 9 Tom Winpenny 0 Sanctus 1:55 Benedictus 3:57 ! Recorded: 23–24 July 2019 at St Saviour’s Church, St Albans, Hertfordshire, UK, Agnus Dei 3:20 @ by kind permission of the Vicar and Churchwardens Dona nobis pacem 3:12 Producer, engineer and editor: Adrian Lucas (Acclaim Productions) Vesperae Pro Festo Sancti Innocentium (1774–87) 36:05 Production assistant: Aaron Prewer-Jenkinson (compiled by Nikolaus Lang, 1772–1837) # $ % ^ & * Booklet notes: Tom Winpenny 1 @ (Text: Psalms 69, v. 1 , 109 , 110 , 111( , 129 , 131 ), Publisher: Carus-Verlag, ed. Armin Kircher – , Aurelius Clemens Prudentius, c.348–c.413 , Luke I: 46–55 ) # ¡ # Edition: Manuscript, ed. Tom Winpenny – $ Deus in adjutorium meum, MH 454 1:02 % Dixit Dominus, MH 294 5:17 ^ Confitebor tibi, MH 304 4:52 Michael Haydn (1737–1806): Missa Sancti Nicolai Tolentini & Beatus vir, MH 304 4:06 Vesperae Pro Festo Sancti Innocentium • Anima Nostra * De profundis clamavi, MH 304 6:21 Michael Haydn was born in Rohrau, an Austrian village Haydn’s first professional appointment (by 1760) was ( Memento Domine David, MH 200 5:58 close to the Hungarian border. -

Mozart and the Tarot” Is an Extract from Tarot in German Countries from the 16Th to the 18Th Century, by Giordano Berti

The article “Mozart and the Tarot” is an extract from Tarot in German countries from the 16th to the 18th Century, by Giordano Berti. The complete booklet is attached to the Tarot deck printed in Salzburg around 1780 by Josef Rauch Miller, now housed at the British Museum, which has kindly granted the reproduction. English translation : Vic Berti Publisher : OM Edizioni, Quarto Inferiore (Bologna - Italy) in collabo- ration with Rinascimento Italian style Art Printed in November 2018 rinascimentoitalianartenglish.wordpress.com/catalog/ ~ 1 ~ Mozart and the Tarot, by Giordano Berti As it has been highlighted in the previous pages of this booklet, during the eighteenth century the game of Tarot spread far and wide within the German speaking countries, being especially popular amongst the bourgeoisie and the aristocracy. This game was espe- cially liked because intelligence prevailed over luck. We know that it was played both in private houses and in public places, particularly in the foyer of theaters, before and after theatri- cal performances or concerts. In these cultural and social environ- ments Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (Salzburg 1756 - Vienna 1791) learned how to play the game of Tarot. Mozart’s passion for this game has been handed down to us thanks to the notes that he himself wrote in 1780, on the pages of his si- ster Nannerl’s diary, where Wolfgang often wrote notes such as word plays which Mozart indulged in, or affectionate, intimate accounts. It is worth recalling that by 1780 Mozart had reached the highest level of frustration for his work as an organist at the court of Prince- Archbishop Hieronymus von Colloredo. -

Neuerwerbungen Bibliothek Januar Bis Juli 2018

1 BEETHOVEN-HAUS BONN Neuerwerbungen Bibliothek Januar bis Juli 2018 Auswahlliste 2018,1 1. Musikdrucke 1.1. Frühdrucke bis 1850 S. 2 1.2. Neuausgaben S. 5 2. Literatur 2.1. Frühdrucke S. 6 2.2. Neuere Bücher und Aufsätze S. 7 2.3. Rezensionen S. 22 3. Tonträger S. 24 2 1. Musikdrucke 1.1. Frühdrucke C 252 / 190 Beethoven, Ludwig van: [Op. 18 – Knight] Air and variations : from the 5th quartet, op. 18 / Beethoven. – 1834 Stereotypie. – Anmerkung am Ende des Notentextes: The Menuetto, p. 46, to / follow at pleasure (es handelt sich um das Menuett aus op. 10,3). – S.a. die spätere Auflage von 1844 (C 252 / 175). In: The musical library : instrumental. – London : Charles Knight. – Vol. I. – 1834. – S. 44-45 C 252 / 190 Beethoven, Ludwig van: [Op. 20 – Knight] A selection from Beethoven's grand septet, arranged for the piano-forte and flute. – [Klavierpartitur]. – 1834 Stereotypie. In: The musical library : instrumental. – London : Charles Knight. – Vol. I. – 1834. – S. 25-33 C 252 / 190 Beethoven, Ludwig van: [Op. 43 – Knight] Introduction and air, from the same / [Beethoven]. – [Klavierauszug]. – 1834 Stereotypie. – Bearbeitung der Nr. 5 (Adagio und Andante quasi Allegretto) aus "Die Geschöpfe des Prometheus" (op. 43,8), "The same" bezieht sich auf die vorangehenden Stücke (Ouvertüre und Nr. 8) ab S. 102. – S.a. die spätere Auflage von 1844 (C 252 / 175). In: The musical library : instrumental. – London : Charles Knight. – Vol. I. – 1834. – S. 109-112 C 49 / 45 Beethoven, Ludwig van: [Op. 49 – Walker] Two sonatas, for the piano forte : op. 49 / composed by L. -

Mozart USA 9/11/05 7:42 Pm Page 4

557023bk Mozart USA 9/11/05 7:42 pm Page 4 Petter Sundkvist Born 1964 in Boliden, Petter Sundkvist has rapidly achieved a leading position on the Swedish musical scene and is today among the most sought after of young Swedish conductors. Having completed his training as a teacher of cello and trumpet at the Piteå College of Music, he then MOZART studied conducting at the Royal University College of Music in Stockholm under Kjell Ingebretsen and Jorma Panula. After graduating in 1991 he also studied contemporary music with the Hungarian composer and conductor Peter Eötvös. He has created for himself a broad and eclectic range of Eine kleine Nachtmusik repertoire and styles. He has conducted more than twenty productions at Swedish opera houses, and has also devoted himself to contemporary music and given over forty first performances of Nordic composers. He has conducted all Swedish orchestras and orchestras in Norway, Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Germany, Great Britain, Serenata notturna Italy, Russia and Slovakia, and from 1996 to 1998 was Associate Conductor of the Swedish Radio Symphony Orchestra. Petter Sundkvist is currently artistic director of the Norrbotten Chamber Orchestra and principal guest- Lodron Night Music No. 1 conductor of the Gävle Symphony Orchestra. Until 2003 he was chief conductor of the Ostgota Wind Symphony and principal guest-conductor of the Swedish Chamber Orchestra. In 2004 he was appointed chief conductor of the Musica Vitae chamber orchestra. His Naxos recordings of works by Stenhammar with the Royal Scottish National Swedish Chamber Orchestra Orchestra, and of Kraus with the Swedish Chamber Orchestra have been much acclaimed in the international press, with the first Kraus release receiving the Cannes Classical Award in 1999. -

DA PONTE DAY ‐ Tuesday, October 7, 2014

DA PONTE DAY http://vocedimeche.net/ ‐ Tuesday, October 7, 2014 Teresa Tièschky and Matthias Winckhler On occasion of the celebration of "Da Ponte Day", the Austrian Cultural Forum presented a fine recital in their acoustically perfect small hall last night. With impeccable scholarship, pianist Wolfgang Brunner assembled a varied program of piano music alternating with arias and duets by Mozart for which Da Ponte wrote the libretti. Two excellent young singers from the Universität Mozarteum Salzburg were brought over to perform and we are delighted to report that they did justice to Mozart's music and Da Ponte's texts. We have written several times about the challenges of singing lieder in a large hall‐‐especially the challenge of creating intimacy. In this case we had the opposite situation, one of scaling back large operatic arias and duets to suit a small hall. This, the two talented young German singers accomplished without sacrificing the grandeur. Mozart must be "in the blood" so to speak. Selections from Nozze di Figaro, Don Giovanni and Così Fan Tutte were presented‐‐all the highlights we have come to know and love. Soprano Teresa Tièschky has the lovely light coloratura that we enjoy hearing and just the right personality for Susanna. She introduced us to an aria we had never before heard which had been specially written for Adriana del Bene detta la Ferrarese for the 1789 revival of the opera. The recitativo proceeded as expected but then...big surprise...no "Deh, vieni non tardar" but "Al desio di chi t'adora". We'd love to hear it again! Miss T. -

Dissertation

DISSERTATION Titel der Dissertation „Johann Baptist Hagenauer (1732–1810) und sein Schülerkreis. Wege der Bildhauerei im 18. und 19. Jahrhundert“ Verfasserin Mag. phil. Mariana Scheu angestrebter akademischer Grad Doktorin der Philosophie (Dr. phil.) Wien, 2014 Studienkennzahl lt. Studienblatt: A 092 315 Dissertationsgebiet lt. Studien- Kunstgeschichte blatt: Betreuerin / Betreuer: Ao. Univ.-Prof. Dr. Ingeborg Schemper-Sparholz Inhalt I. Einleitung....................................................................................................................... 3 II. Forschungsstand ......................................................................................................... 13 III. Johann Baptist Hagenauer......................................................................................... 23 1. Hagenauers bildhauerisches Schaffen in Salzburg ................................................ 24 1.1. Die Salzburger Bildhauerwerkstatt ................................................................. 27 2. Hagenauer an der Wiener Akademie der bildenden Künste .................................. 30 2.1. Die Bildhauerprofessur ................................................................................... 31 2.2. Die Erzverschneiderschule an der Wiener Akademie .................................... 38 2.2.1. Zur Bedeutung der Schule als künstlerische Ausbildungsstätte ........... 64 3. Das künstlerische Schaffen zwischen 1780 und 1810 ........................................... 67 IV. Die Schüler Johann Baptist Hagenauers -

Joseph Woelfl

Institut für Österreichische Musikdokumentation Österreichische für Institut Musiksammlung der Österreichischen Nationalbibliothek Österreichischen der Musiksammlung Im Duell mit Beethoven – Joseph Woelfl Mittwoch, 20. November 2013, 19:30 Uhr Palais Mollard, Salon Hoboken 1010 Wien, Herrengasse 9 Eintritt frei Programm Werke von Joseph Woelfl Sonate über „Die Schöpfung“ A-Dur op.14, Nr. 1 Allegro moderato – Adagio – Allegro Elena Denisova / Violine Alexei KornienKo / Klavier Die Geister des Sees Eine Ballade von Fräulein Amalie von Imhof WoO 20,1 Christa ratzenböcK / Sopran Margit HaiDer-DecHant / Klavier Sonate über „Die Schöpfung“ D-Dur op.14, Nr. 2 Allegro maestoso – Moderato – Allegro Elena Denisova / Violine Alexei KornienKo / Klavier Thomas Leibnitz im Gespräch mit Margit HaiDer- DecHant 2 Zu Leben und Werk Joseph Woelfls Jugend in Salzburg, Warschau und Wien Joseph Woelfl, am 24. Dezember 1773 als Sohn des fürstbischöflichen Verwaltungsjuristen Johann Paul Woelfl in Salzburg geboren, wuchs in dem Haus auf, in dem auch der Salzburger Hoforganist Michael Haydn wohnte. Die Familie gehörte dem einfachen Adel an. Es ist unklar, ob Woelfl seine frühe musikalische Ausbildung beim jüngeren Haydn erhielt oder bei Leopold Mozart, dem Vizekapellmeister der Hofkapelle, der nachweislich mit Woelfls Vater bekannt war. Neue Forschungen legen nahe, dass er mit der Ausbildung auf Violine und Klavier bei Leopold Mozart begann. Bereits als siebenjähriger Knabe trat er öffentlich als Violinvirtuose auf. Seine offensichtliche musikalische Begabung führte zu seiner Aufnahme ins „Kapellhaus“, ein eigens für die Unterrichtung der Domsängerknaben errichtetes Internatsgebäude. Nun waren Michael Haydn und Leopold Mozart auch offiziell seine Lehrer. Die religiös streng reglementierte Ausbildung umfas- ste neben dem Musikunterricht auch die Aneignung von naturwissenschaftlichem und sprachlichem Allgemeinwissen. -

Überall Musik! Der Salzburger Fürstenhof – Ein Zentrum Europäischer Musikkultur 1587-1807

Überall Musik! Der Salzburger Fürstenhof – ein Zentrum europäischer Musikkultur 1587-1807 Überall Musik! Der Salzburger Fürstenhof – ein Zentrum europäischer Musikkultur 1587-1807 Die große musikalische Tradition Salzburgs reicht weit zurück und ist untrennbar mit der Geschichte und den Räumen des Residenz- und Dombereichs verbunden. Das DomQuartier beleuchtet die Höhepunkte dieser ruhmreichen Musikgeschichte ab WolF Dietrich von Raitenau (reg. 1587-1612) bis zur AuFlösung der HoFkapelle an historischen Orten und erzählt in den Prunkräumen der Residenz und im Nordoratorium des Doms von Fest- Spielen für hohe Gäste, von großen und kleinen Feiern zu besonderen Anlässen, von Abendunterhaltungen in exklusivem Rahmen und von Musikern und Komponisten, die ein unentbehrlicher Bestandteil dieses breitgeFächerten Fürstlichen Festbetriebes waren. In der Langen Galerie St. Peter kommt es zu einem „Nachklang großer Zeiten“. Eine musikalische Entdeckungsreise durch mehr als 200 Jahre Salzburger Musikgeschichte an den Originalspielstätten In Salzburg herrschte ein facettenreiches kulturelles Leben, als Mittelpunkt fungierte bis zur Säkularisation 1803 der Hof des Fürsterzbischofs. Musik spielte in diesem Zusammenhang eine tragende Rolle, war ein integraler und unentbehrlicher Bestandteil der HerrschaFtsinszenierung, der repraesentatio majestatis. Das DomQuartier beleuchtet diese ruhmreiche Musikgeschichte an den historischen Orten des musikalischen Geschehens, umfasst es doch mit den Prunkräumen der Residenz und dem Dombereich einzigartige originale Spielstätten weltlicher und geistlicher Musik. Das ist ein einzigartiges Atout. Die Ausstellung kann die Themen in den entsprechenden, inhaltlich passenden Räumen behandeln, die Räume selbst sind ein Ausstellungsobjekt an sich. 2 Diese unmittelbare Verbindung von Raum und Klang ermöglicht ein besonderes Ausstellungserlebnis. Die Ausstellung verfolgt zwei Erzählstränge, die Festkultur sowie die Stellung der Musik und der Musiker innerhalb dieses Repräsentationssystems mit seinen speziellen Produktionsbedingungen.