Scanning Behaviour and Spatial Niche

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Itinerary

Itinerary for Birding Formosa October 24 - Nov. 2, 2015 *Bold for endemics Day Date/Meals Due to Dateline - Flights from SFO depart on Oct. 22 to arrive TPE on Oct. 23 0 Oct. 23/Fri. Arriving Taoyuan International Airport (TPE) -Air fare not included -/-/- Taking Hotel's shuttle bus from terminal 1/2 to the hotel and checking in by yourselves (early check-in charge may apply if checking in before 3:00p.m.) Overnight: Hotel near Taipei Taoyuan Airport (not included in base cost) Breakfast and trip inception at Novotel 1 Oct. 24/Sat. Bird watching in Taipei Botanic Garden -/L/D Looking for Black-browed Barbet , Malayan Night-heron, Japanese White-eye, Gray Treepie, Black-napped Blue Monarch Transferring to Hualian(4 hours) Overnight: Hualian 2 Oct. 25/Sun. Bird watching in Hualien & Taroko National Park (2000+ m/6600+ ft) B/L/D Looking for Styan’s Bulbul, Taiwan Whistling Thrush Transferring to Cingjing(4 hours) Overnight: Cingjing 3 Oct. 26/Mon. Bird watching in Mt. Hehuan Route (3000+ m/9900+ ft) B/L/D Looking for White-whiskered Laughingthrush, Flamecrest, Collared Bush-Robin, Alpine Accentor, Vinaceous Rosefinch, Coal Tit, Winter Wren, Taiwan Fulvetta Transferring to Huisun(1.5 hours) Overnight: Huisun 4 Oct. 27/Tue. Bird watching in Huisun (1000 m/3300 ft) B/L/D Looking for White-eared Sibia, Taiwan Yuhina, Yellow Tit, Fire-breasted Flowerpeckers, Formosan Magpie, Taiwan Barbet , Gray-cheeked Fulvetta, Chinese Bamboo Partridge, Malayan Night Heron Transferring to Alishan(3+ hours) Overnight: Alishan 5 Oct. 28/Wed. Bird watching in Alishan (2000+ m/6600+ ft) and Tataka, Yushan (2600m/8600 ft) B/L/D Looking for Collared Bush Robin, Taiwan Yuhina, Yellow Tit , Rufouscrowned Laughingthrush, Taiwan Wren-Babbler , Coal Tit, Green-backed Tit, Black-throated Tit, Flamecrest, Mikado Pheasant, Steere’s Liocichla , Taiwan Bush Warbler, Rusty Laughingthrush Transferring to Tainan(2.5 hours) Overnight: Tainan 6 Oct. -

Best of the Baltic - Bird List - July 2019 Note: *Species Are Listed in Order of First Seeing Them ** H = Heard Only

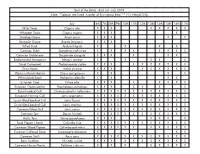

Best of the Baltic - Bird List - July 2019 Note: *Species are listed in order of first seeing them ** H = Heard Only July 6th 7th 8th 9th 10th 11th 12th 13th 14th 15th 16th 17th Mute Swan Cygnus olor X X X X X X X X Whopper Swan Cygnus cygnus X X X X Greylag Goose Anser anser X X X X X Barnacle Goose Branta leucopsis X X X Tufted Duck Aythya fuligula X X X X Common Eider Somateria mollissima X X X X X X X X Common Goldeneye Bucephala clangula X X X X X X Red-breasted Merganser Mergus serrator X X X X X Great Cormorant Phalacrocorax carbo X X X X X X X X X X Grey Heron Ardea cinerea X X X X X X X X X Western Marsh Harrier Circus aeruginosus X X X X White-tailed Eagle Haliaeetus albicilla X X X X Eurasian Coot Fulica atra X X X X X X X X Eurasian Oystercatcher Haematopus ostralegus X X X X X X X Black-headed Gull Chroicocephalus ridibundus X X X X X X X X X X X X European Herring Gull Larus argentatus X X X X X X X X X X X X Lesser Black-backed Gull Larus fuscus X X X X X X X X X X X X Great Black-backed Gull Larus marinus X X X X X X X X X X X X Common/Mew Gull Larus canus X X X X X X X X X X X X Common Tern Sterna hirundo X X X X X X X X X X X X Arctic Tern Sterna paradisaea X X X X X X X Feral Pigeon ( Rock) Columba livia X X X X X X X X X X X X Common Wood Pigeon Columba palumbus X X X X X X X X X X X Eurasian Collared Dove Streptopelia decaocto X X X Common Swift Apus apus X X X X X X X X X X X X Barn Swallow Hirundo rustica X X X X X X X X X X X Common House Martin Delichon urbicum X X X X X X X X White Wagtail Motacilla alba X X -

British Birds |

VOL. LI DECEMBER No. 12 1958 BRITISH BIRDS CONCEALMENT AND RECOVERY OF FOOD BY BIRDS, WITH SOME RELEVANT OBSERVATIONS ON SQUIRRELS By T. J. RICHARDS THE FOOD-STORING INSTINCT occurs in a variety of creatures, from insects to Man. The best-known examples are found in certain Hymenoptera (bees, ants) and in rodents (rats, mice, squirrels). In birds food-hoarding- has become associated mainly with the highly-intelligent Corvidae, some of which have also acquired a reputation for carrying away and hiding inedible objects. That the habit is practised to a great extent by certain small birds is less generally known. There is one familiar example, the Red- backed Shrike (Lanius cristatus collurio), but this bird's "larder" does not fall into quite the same category as the type of food- storage with which this paper is concerned. Firstly, the food is not concealed and therefore no problem arises regarding its recovery, and secondly, since the bird is a summer-resident, the store cannot serve the purpose of providing for the winter months. In the early autumn of 1948, concealment of food by Coal Tit (Parns ater), Marsh Tit (P. palustris) and Nuthatch (Sitta enropaea) was observed at Sidmouth, Devon (Richards, 1949). Subsequent observation has confirmed that the habit is common in these species and has also shown that the Rook (Corvus jrngilegus) will bury acorns [Querents spp.) in the ground, some- • times transporting the food to a considerable distance before doing so. This paper is mainly concerned with the food-storing behaviour of these four species, and is a summary of observations made intermittently between 1948 and 1957 in the vicinity of Sidmouth. -

Movements of Tits in Europe in 1959 and After by Stanley Cramp

Movements of tits in Europe in 1959 and after By Stanley Cramp INTRODUCTION AN EARLIER PAPER (Cramp, Pettet and Sharrock 1963) described the irruptions of Great, Blue and Coal Tits (Parus major, caerukm and ater) into the British Isles in the autumn of 1957 and showed that these formed part of considerable movements of all three species over large areas of western and central Europe, Although the Coal Tit was known to be an irruption species in some parts of Europe, it had not been generally realised that Great and Blue Tits, normally continued... 237 BRITISH BIRDS sedentary birds, also move considerable distances at times of peak population. The examination of earlier observations showed that such movements had occurred on a large scale at irregular intervals (in the British Isles the previous irruption of any size had been in 1949) and had probably varied in extent and nature in different years. There were again indications of irruption movements during the autumn of 1959, and, as before, appeals for relevant observations were made in ornithological journals and on the B.B.C In the event, the irruptions into the British Isles proved to be on a much smaller scale than in 1957, but over considerable areas of Europe they were much larger. In 1957 there was strong evidence that the irruptions were due to the high numbers of tits surviving in the previous mild winter, and in 1959 also tit numbers appear to have been unusually high, due both to a mild winter in many countries and to a good summer which resulted in a high fledging success. -

Suttonella Ornithocola Infection in Garden Birds

Suttonella ornithocola infection in Garden Birds Agent Suttonella ornithocola is a recently discovered bacterium in the family Cardiobacteriaceae. Species affected Suttonella ornithocola infection has been most commonly observed in blue tit (Cyanistes caeruleus); however, other birds within the tit families (Paridae and Aegithalidae) are also susceptible to infection, such as coal tit (Periparus ater), long-tailed tit (Aegithalos caudatus) and great tit (Parus major). Suttonella ornithocola infection has not yet been diagnosed in the other groups of British garden bird species. Pathology Suttonella ornithocola causes lung disease in affected tits. Microscopic examination of the lung revealed a “pneumonia-like” condition associated with S. ornithocola infection. Signs of disease Birds affected by S. ornithocola infection tend to show non-specific signs of ill health, for example lethargy and fluffed- up plumage. In addition, they can show breathing difficulties such as gasping. Wild birds suffering from a variety of conditions can exhibit similar signs of disease and there are no characteristic signs of S. ornithocola infection that allow it to be diagnosed without specialist veterinary examination. Affected birds are often thin, indicating that the disease may progress over the course of several days. Disease transmission Relatively little is known about S. ornithocola in British tit species. Since the bacterium causes a lung infection, aerosol or air-borne infection (i.e. cloud or mist of infectious agent released by coughing or sneezing) is thought to be the most likely route of transmission between birds. The length of time that S. ornithocola can survive in the environment, and whether this is important in the disease transmission, is unknown. -

Bird Spotting Guide

Bird spotting guide Chaffinch Chaffinch Pretty, cute and very common, but too shy to come and say hello. About Breeding Male chaffinches have a Chaffinch breeding season striking appearance and can is between April and July. be identified by their pinkish They typically lay one brood breast and underparts, containing 4-5 eggs. blue crown, chestnut back Eggs vary in colour and can be and yellow tinted feathers. blue/green or red/brown. Females have more brown Average Height = 14cm colouring and paler wings. Average Wingspan = 26cm Did you know? Diet = Insects and seeds In the UK there are 6.2 million Habitat = Woodland, farmlands breeding pairs of Chaffinches and gardens Blackbird Like their song, the Blackbirds are bold characters, with Blackbird soundtrack for all the comings and goings in the garden. About Breeding Males are almost completely Can lay up to five broods of black with the exception of 3-4 eggs between March and a yellow bill and ring around September. Nests are usually their eye. Despite their formed of grass and twigs and name females are actually located in the fork of a tree or predominantly brownie-red bush. Eggs are green/blue in in colour. colour with red blotches. Average Height = 24cm The incubation period usually Average Wingspan = 36cm lasts between 13 and 14 days. Diet = Mainly insects, fruit & berry Did you know? Habitat = Woodlands, gardens and parks Blackbirds love to sunbathe with their wings spread out 1 Bird spotting guide Wren Wren A tiny, busy and hardy bird. For such a small bird it has a remarkably loud voice. -

Taiwan: Formosan Endemics Set Departure Tour 14Th – 27Th April, 2013

Taiwan: Formosan Endemics Set departure tour 14th – 27th April, 2013 Tour leader : Charley Hesse Report & photos by Charley Hesse Mikado Pheasant is one of the most beautiful endemics and a source of pride for Taiwanese people. This year’s Taiwan Set Departure tour was our most successful to date, with an impressive 217 bird species recorded. We saw all 23 Clements endemics easily thanks to our ever- growing knowledge base with some great new stakeouts for some of the more difficult species. With our Taiwan office up and running, logistics went smoothly and last minute changes due to internal flight cancellations were handled with ease, even netting us some unexpected additions like Japanese Yellow Bunting. With fine weather at Dashueshan at the beginning of the tour, we accumulated endemics quickly, leaving us extra time to search for more difficult birds. Highlights were many and aside from the spectacular Mikado & Swinhoe’s Pheasants, we found the threatened Black-faced Spoonbill and Fairy Pitta, and enjoyed great views of attractive endemics like Taiwan Partridge, Flamecrest, Formosan Magpie and Formosan Whistling-Thrush as well as a full house of endemic laughingthrushes and scimitar-babblers. We were also lucky enough to find the rarely seen Formosan Serow, a kind of mountain goat. We birded everything from mountain forests, grasslands, mudflats and the rugged island of Lanyu and we were treated to breathtaking scenery, delicious food and charmed by the wonderfully friendly people of this island. Taiwan has a surprising amount to offer and never fails to leave a lasting impression. Tropical Birding www.tropicalbirding.com 1 14 th April – Botanical Gardens & Riverside Park Today was arrival day and after lunch we met up for our first birding of the trip at the Taipei Botanical gardens, which is a great place to get to grips with the commoner resident birds on the island. -

394 Great Tit

Javier Blasco-Zumeta & Gerd-Michael Heinze Laboratorio Virtual Ibercaja 394 Great Tit AGEING 3 types of age can be recognized: Juvenile with very dull yellow and black co- lours; yellowish cheek patch without complete black border along lower edge. 1st year autumn/2nd year spring with moult limit between moulted greater coverts, with bluish edges, and grey juvenile primary co- verts; some birds with moult limit between tertials or between tertials and secondaries. Adult with all wing feathers with bluish ed- ges. Great Tit. Adult. Male (06-I). Great Tit. GREAT TIT (Parus major ) Extent of postjuve- IDENTIFICATION n i l e 12-14 cm. Black head and throat, with a white moult. patch on cheek and nape; yellow underparts, with a black band; greenish upperparts and wings with one pale bar. SIMILAR SPECIES PHENOLOGY Recalls a Coal Tit which is smaller, lacks a black band on breast, has greyish upperparts I II III IV V VI VII VIII IX X XI XII and two white bars on wing. STATUS IN ARAGON Resident. Widely distributed throughout the Region, absent only from the highest areas of the Pyrenees and the most deforested zones of the Ebro Basin. Coal Tit SEXING Male with deep black on head and throat; broad black band on breast and belly. Female with dull black on head and throat; narrow black band on breast and belly. Juveniles can- not be sexed using plumage characters. MOULT Complete postbreeding moult, usually finis- hed in October. Partial postjuvenile moult in- cluding body feathers, lesser and median co- Great Tit. Adult. -

Great Spotted Woodpecker (Dendrocopos Major) Absent from Ireland for Hundreds of Years, the Great Spotted Woodpecker Has Recently Re-Colonised Co

Bird diversity in Irish forests Ireland’s forest estate has altered significantly over time through the actions of man. Far fewer specialist bird species are found here compared with mainland Europe, for several reasons including island biogeography, and the distinct west to east declining gradient in bird species richness across Europe. Bird life in coniferous forests in Ireland is less varied than that of broadleaved woodlands, though both are important habitats for birds. Appropriate management of our forests can significantly increase their suitability for birds, and allow us to maximise forest bird diversity in Ireland. Great Spotted Woodpecker (Dendrocopos major) absent from Ireland for hundreds of years, the Great Spotted Woodpecker has recently re-colonised co. Wicklow. there are now at least 17 breeding pairs in the country, an exciting Photo: Dick Coombes development following such a long absence. Woodpeckers are ‘woodland engineers’ and several animals benefit from the crevices and holes that they create. they are found predominantly in oak woodlands, where they feed on insects from deadwood, and on tree seeds and birds’ eggs. Hen HarrIer (Circus cyaneus) Hen Harriers are among our rarest and most distinctive birds of prey, and have become much rarer in recent centuries. traditionally regarded as birds of open upland habitats, many now nest and hunt in young conifer plantations, taking advantage of the abundance of Photo: Richard Mills shrub cover and prey items such as small birds and mammals. treecreeper (Certhia familiaris) these small birds are closely associated with woodland habitats in Ireland, reaching the highest densities in native broadleaved woodlands. as their name suggests, these birds ‘creep’ vertically Photo: Biopix.dk up trunks and branches of trees in search of food. -

Changes in Foraging Behaviour of the Coal Tit (; Parus Ater Due to Snow Cover

249 CHANGES IN FORAGING BEHAVIOUR OF THE COAL TIT (; PARUS ATER DUE TO SNOW COVER LLUfs BROTONS Brotons L. 1997. Changes in foraging behaviour of the Coal Tit Parus ater due to snow cover. Ardea 85: 249-257. This paper studies the foraging behaviour of the Coal Tit Parus ater, a small passerine wintering in mountain coniferous forests in the Pyrenees. We compared tree site use and the foraging techniques of birds, (1) under snowy conditions, when snow covered the outer substrates of pines, and (2) under snow-free conditions. Under snowy conditions, birds foraged in the lower and inner parts of trees, using trunks and thick branches as their main foraging substrate. During normal, snow-free conditions, birds used upper and outer parts of trees feeding mainly on pine cones and needles. Move ment patterns of individuals differed from one condition to the other. Dur ing snow free conditions, birds used more costly energy methods, mainly flight and hanging position, while in snowy conditions they used lower en ergy consuming methods, mainly hopping. Our results support Norberg's hypothesis (1977) that when the prospects of obtaining prey increase, for aging methods requiring higher energy consumption can be used. Key words: Parus ater - tree snow cover - foraging behaviour - movement patterns - energetic costs Dept. Animal Biology (Vertebrates), University ofBarcelona, Av. Diagonal 645, 08028 Barcelona, Spain; E-mail: [email protected]. INTRODUCTION ergy expenditure (Grubb 1979, Carrascal 1988, Lens 1996, Wachob 1996) and maximize prey in Weather conditions are a significant factor in de take profitability (Pyke 1984, Stephens & Krebs termining the way in which birds interact with 1986). -

Egg-Laying Behavior in Tits1

SHORT COMMUNICATIONS 863 The Condor98:863-865 0 The CooperOrnithological Society 1996 EGG-LAYING BEHAVIOR IN TITS1 SVEINHAFTORN Norwegian Universityof Scienceand Technology,The Museum, N-7004 Trondheim,Norway Key words: Great Tit: Parus major; Willow Tit; P. The first sign of approaching egg-laying was usually montanus; Marsh Tit; P. palustris; Coal Tit; P. ater; intensifiedbreathing, occasionally with rhythmic open- egg-layingbehavior. ing and closingof the bill that pointed either horizon- tally forwards or more or less upwards. The head was Like most passetines,tits lay their eggs early in the drawn in and the body featherswere somewhat fluffed out; the Coal Tit in addition raised its crown feathers. morning. Traditionally, ornithologists determine lay- ing times indirectly by checking the nest content at The tail was kept horizontal or elevated up to about different times of the day. Only a few personsseem to 45”. Then the tip of the tail startednodding movements have actually witnessed the egg-layingitself. Haftom synchronouslywith rhythmic depressionsof the rump. (1966) gave a preliminary descriptionin Norwegian of These movements which apparently were caused by throes of parturition when the egg traveled down the egg-layingbehavior in tits. Subsequently,Flanagan and oviduct, were almost invisible to begin with but gath- Morris (1975) published photos of a female Blue Tit (Purus caeruleus)during egg-laying.Over the years I ered in strengthand ended with a suddenelevation of have observed egg-layingin many females of several the rump (Fig. 1, top) that marked the moment of egg- tit speciesand am therefore able to give a more com- laying. Then the bird “froze” in a motionless posture, prehensive quantitative description of this phenome- termed “recovery phase” (Fig. -

ROOSTING HABITS of the IRISH GOAL-TIT, with SOME OBSERVATIONS on OTHER HABITS (Plate 43)

(326) ROOSTING HABITS OF THE IRISH GOAL-TIT, WITH SOME OBSERVATIONS ON OTHER HABITS BY ROBERT F. RUTTLEDGE. (Plate 43). THE observation in The Handbook, Vol. i, p, 256, stating that data on normal roosting habits of the Coal-Tit were scanty, led me to pay particular attention to this subject. My observations are confined to the Irish Coal-Tit (Parus ater hibemicus). The results are those of over three years' study of a limited number of birds in Co. Ma}'o. The locality where observations were made is fairly exposed, but with considerable shelter in the form of gardens, outhouses, trees and scrubby woods. There are a number of difficulties in the way of detailed study of this species, chief of which is the extreme difficulty of seeing rings on marked birds in thick foliage and on such a restless bird. In summer, in particular, it is very hard to trace birds to their roosts, with the result that there is a paucity of observations at this season. When working alone, or with only one companion, it is extremely difficult to follow up the rapid movements of the birds as they travel through thickets or in high tree-tops prior to going to rcost. Observations have, therefore, at times been rather disjointed, especially when a bird changes its roost, thus necessitating renewed search. Although primarily the work was in connexion with roosting- habits, other habits have claimed attention and some notes on them are given. I am much indebted to John Barlce for the photographs of two typical roost-sites.