Food Storing in the Paridae

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Printable PDF Format

Field Guides Tour Report Taiwan 2020 Feb 1, 2020 to Feb 12, 2020 Phil Gregory & local guide Arco Huang For our tour description, itinerary, past triplists, dates, fees, and more, please VISIT OUR TOUR PAGE. This gorgeous male Swinhoe's Pheasant was one of the birds of the trip! We found a pair of these lovely endemic pheasants at Dasyueshan. Photo by guide Phil Gregory. This was a first run for the newly reactivated Taiwan tour (which we last ran in 2006), with a new local organizer who proved very good and enthusiastic, and knew the best local sites to visit. The weather was remarkably kind to us and we had no significant daytime rain, somewhat to my surprise, whilst temperatures were pretty reasonable even in the mountains- though it was cold at night at Dasyueshan where the unheated hotel was a bit of a shock, but in a great birding spot, so overall it was bearable. Fog on the heights of Hohuanshan was a shame but at least the mid and lower levels stayed clear. Otherwise the lowland sites were all good despite it being very windy at Hengchun in the far south. Arco and I decided to use a varied assortment of local eating places with primarily local menus, and much to my amazement I found myself enjoying noodle dishes. The food was a highlight in fact, as it was varied, often delicious and best of all served quickly whilst being both hot and fresh. A nice adjunct to the trip, and avoided losing lots of time with elaborate meals. -

Small Protection Plates Against Marten Predation on Nest Boxes

Appl. Entomol. Zool. 40 (4): 575–577 (2005) http://odokon.ac.affrc.go.jp/ Small protection plates against marten predation on nest boxes Noriyuki YAMAGUCHI,1,*,† Katsura M. KAWANO,1 Yasuhiro YAMAGUCHI2 and Takashi SAITO3 1 Department of Biology, Faculty of Science, Kyushu University; Fukuoka 812–8581, Japan 2 Wildlife Management Laboratory, National Agricultural Research Center; Tsukuba, Ibaraki 305–8666, Japan 3 Yamashina Institute for Ornithology; Abiko, Chiba 270–1145, Japan (Received 27 October 2004; Accepted 3 June 2005) Abstract The nest box is a powerful research tool for ecological and conservational studies of birds and several other cavity nesters. However, skilful predators such as martens sometimes invade nest boxes, thus disturbing researches. To pro- tect nest boxes against predation by martens, we attached a small plate inside the nest box below the entrance hole, and we report here on the advantage of this device. In 1999 and 2000, respectively, 73.0% and 64.8% nest boxes were used by the Great Tit and the Varied Tit. After fitting boxes with the plate in 2000, the percentage of predated nests by martens decreased from 22.4% to 5.9%, and the percentage of successful nests increased from 29.3% to 43.8%. Key words: Marten; nest box; protection against predation (dominant overstory trees are Machilus thunbergii, INTRODUCTION Quercus glauca, Styrax japonica, and Magnolia The nest box is a powerful and popular research obovata), ranging in elevation from 210 m to 380 m tool for ecological and conservational studies. above sea level. Dominant secondary cavity nesters Many researchers commonly use nest boxes, notic- are Varied Tits (Parus varius) and Great Tits ing careful regard to estimate the results that they (Parus major). -

Natural History of Japanese Birds

Natural History of Japanese Birds Hiroyoshi Higuchi English text translated by Reiko Kurosawa HEIBONSHA 1 Copyright © 2014 by Hiroyoshi Higuchi, Reiko Kurosawa Typeset and designed by: Washisu Design Office Printed in Japan Heibonsha Limited, Publishers 3-29 Kanda Jimbocho, Chiyoda-ku Tokyo 101-0051 Japan All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means without permission in writing from the publisher. The English text can be downloaded from the following website for free. http://www.heibonsha.co.jp/ 2 CONTENTS Chapter 1 The natural environment and birds of Japan 6 Chapter 2 Representative birds of Japan 11 Chapter 3 Abundant varieties of forest birds and water birds 13 Chapter 4 Four seasons of the satoyama 17 Chapter 5 Active life of urban birds 20 Chapter 6 Interesting ecological behavior of birds 24 Chapter 7 Bird migration — from where to where 28 Chapter 8 The present state of Japanese birds and their future 34 3 Natural History of Japanese Birds Preface [BOOK p.3] Japan is a beautiful country. The hills and dales are covered “satoyama”. When horsetail shoots come out and violets and with rich forest green, the river waters run clear and the moun- cherry blossoms bloom in spring, birds begin to sing and get tain ranges in the distance look hazy purple, which perfectly ready for reproduction. Summer visitors also start arriving in fits a Japanese expression of “Sanshi-suimei (purple mountains Japan one after another from the tropical regions to brighten and clear waters)”, describing great natural beauty. -

GRUNDSTEN Japan 0102 2016

Birding Japan (M. Grundsten, Sweden) 2016 Japan, January 30th - February 14th 2016 Karuizawa – E Hokkaido – S Kyushu – Okinawa – Hachijo-jima Front cover Harlequin Duck Histrionicus histrionicus, common along eastern Hokkaido coasts. Photo: Måns Grundsten Participants Måns Grundsten ([email protected], compiler, most photos), Mattias Andersson, Mattias Gerdin, Sweden. Highlights • A shy Solitary Snipe in the main stream at Karuizawa. • Huge-billed Japanese Grosbeaks and a neat 'griseiventris' Eurasian Bullfinch at Karuizawa. • A single Rustic Bunting behind 7/Eleven at Karuizawa. • Amazing auks from the Oarai-Tomakomai ferry. Impressive numbers of Rhinoceros Auklet! • Parakeet Auklet fly-bys. • Blakiston's Fish Owl in orderly fashion at Rausu. • Displaying Black Scoters at Notsuke peninsula. • Majestic Steller's Sea Eagles in hundreds. • Winter gulls at Hokkaido. • Finding a vagrant Golden-crowned Sparrow at Kiritappu at the same feeders as Asian Rosy Finches. • No less than 48(!) Rock Sandpipers. • A lone immature Red-faced Cormorants on cliffs at Cape Nosappu. • A pair of Ural Owls on day roost at Kushiro. • Feeding Ryukyu Minivets at Lake Mi-ike. • Fifteen thousand plus cranes at Arasaki. • Unexpectedly productive Kogawa Dam – Long-billed Plover. • Saunders's Gulls at Yatsushiro. • Kin Ricefields on Okinawa, easy birding, lots of birds, odd-placed Tundra Bean Geese. • Okinawa Woodpecker and Rail within an hour close to Fushigawa Dam, Yanbaru. • Whistling Green Pigeon eating fruits in Ada Village. • Vocal Ryukyu Robins. • Good shorebird diversity in Naha. • Male Izu Thrush during a short break on Hachijo-jima. • Triple Albatrosses! • Bulwer's Petrel close to the ship. Planning the trip – Future aspects When planning a birding trip to Japan there is a lot of consideration to be made. -

The Itinerary

Itinerary for Birding Formosa October 24 - Nov. 2, 2015 *Bold for endemics Day Date/Meals Due to Dateline - Flights from SFO depart on Oct. 22 to arrive TPE on Oct. 23 0 Oct. 23/Fri. Arriving Taoyuan International Airport (TPE) -Air fare not included -/-/- Taking Hotel's shuttle bus from terminal 1/2 to the hotel and checking in by yourselves (early check-in charge may apply if checking in before 3:00p.m.) Overnight: Hotel near Taipei Taoyuan Airport (not included in base cost) Breakfast and trip inception at Novotel 1 Oct. 24/Sat. Bird watching in Taipei Botanic Garden -/L/D Looking for Black-browed Barbet , Malayan Night-heron, Japanese White-eye, Gray Treepie, Black-napped Blue Monarch Transferring to Hualian(4 hours) Overnight: Hualian 2 Oct. 25/Sun. Bird watching in Hualien & Taroko National Park (2000+ m/6600+ ft) B/L/D Looking for Styan’s Bulbul, Taiwan Whistling Thrush Transferring to Cingjing(4 hours) Overnight: Cingjing 3 Oct. 26/Mon. Bird watching in Mt. Hehuan Route (3000+ m/9900+ ft) B/L/D Looking for White-whiskered Laughingthrush, Flamecrest, Collared Bush-Robin, Alpine Accentor, Vinaceous Rosefinch, Coal Tit, Winter Wren, Taiwan Fulvetta Transferring to Huisun(1.5 hours) Overnight: Huisun 4 Oct. 27/Tue. Bird watching in Huisun (1000 m/3300 ft) B/L/D Looking for White-eared Sibia, Taiwan Yuhina, Yellow Tit, Fire-breasted Flowerpeckers, Formosan Magpie, Taiwan Barbet , Gray-cheeked Fulvetta, Chinese Bamboo Partridge, Malayan Night Heron Transferring to Alishan(3+ hours) Overnight: Alishan 5 Oct. 28/Wed. Bird watching in Alishan (2000+ m/6600+ ft) and Tataka, Yushan (2600m/8600 ft) B/L/D Looking for Collared Bush Robin, Taiwan Yuhina, Yellow Tit , Rufouscrowned Laughingthrush, Taiwan Wren-Babbler , Coal Tit, Green-backed Tit, Black-throated Tit, Flamecrest, Mikado Pheasant, Steere’s Liocichla , Taiwan Bush Warbler, Rusty Laughingthrush Transferring to Tainan(2.5 hours) Overnight: Tainan 6 Oct. -

Best of the Baltic - Bird List - July 2019 Note: *Species Are Listed in Order of First Seeing Them ** H = Heard Only

Best of the Baltic - Bird List - July 2019 Note: *Species are listed in order of first seeing them ** H = Heard Only July 6th 7th 8th 9th 10th 11th 12th 13th 14th 15th 16th 17th Mute Swan Cygnus olor X X X X X X X X Whopper Swan Cygnus cygnus X X X X Greylag Goose Anser anser X X X X X Barnacle Goose Branta leucopsis X X X Tufted Duck Aythya fuligula X X X X Common Eider Somateria mollissima X X X X X X X X Common Goldeneye Bucephala clangula X X X X X X Red-breasted Merganser Mergus serrator X X X X X Great Cormorant Phalacrocorax carbo X X X X X X X X X X Grey Heron Ardea cinerea X X X X X X X X X Western Marsh Harrier Circus aeruginosus X X X X White-tailed Eagle Haliaeetus albicilla X X X X Eurasian Coot Fulica atra X X X X X X X X Eurasian Oystercatcher Haematopus ostralegus X X X X X X X Black-headed Gull Chroicocephalus ridibundus X X X X X X X X X X X X European Herring Gull Larus argentatus X X X X X X X X X X X X Lesser Black-backed Gull Larus fuscus X X X X X X X X X X X X Great Black-backed Gull Larus marinus X X X X X X X X X X X X Common/Mew Gull Larus canus X X X X X X X X X X X X Common Tern Sterna hirundo X X X X X X X X X X X X Arctic Tern Sterna paradisaea X X X X X X X Feral Pigeon ( Rock) Columba livia X X X X X X X X X X X X Common Wood Pigeon Columba palumbus X X X X X X X X X X X Eurasian Collared Dove Streptopelia decaocto X X X Common Swift Apus apus X X X X X X X X X X X X Barn Swallow Hirundo rustica X X X X X X X X X X X Common House Martin Delichon urbicum X X X X X X X X White Wagtail Motacilla alba X X -

Habitat Modelling and the Ecology of the Marsh Tit (Poecile Palustris)

HABITAT MODELLING AND THE ECOLOGY OF THE MARSH TIT (POECILE PALUSTRIS) RICHARD K BROUGHTON A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of Bournemouth University for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy August 2012 Bournemouth University in collaboration with the Centre for Ecology & Hydrology This copy of the thesis has been supplied on condition that anyone who consults it is understood to recognise that its copyright rests with its author and due acknowledgement must always be made of the use of any material contained in, or derived from, this thesis. 2 ABSTRACT Richard K Broughton Habitat modelling and the ecology of the Marsh Tit (Poecile palustris) Among British birds, a number of woodland specialists have undergone a serious population decline in recent decades, for reasons that are poorly understood. The Marsh Tit is one such species, experiencing a 71% decline in abundance between 1967 and 2009, and a 17% range contraction between 1968 and 1991. The factors driving this decline are uncertain, but hypotheses include a reduction in breeding success and annual survival, increased inter-specific competition, and deteriorating habitat quality. Despite recent work investigating some of these elements, knowledge of the Marsh Tit’s behaviour, landscape ecology and habitat selection remains incomplete, limiting the understanding of the species’ decline. This thesis provides additional key information on the ecology of the Marsh Tit with which to test and review leading hypotheses for the species’ decline. Using novel analytical methods, comprehensive high-resolution models of woodland habitat derived from airborne remote sensing were combined with extensive datasets of Marsh Tit territory and nest-site locations to describe habitat selection in unprecedented detail. -

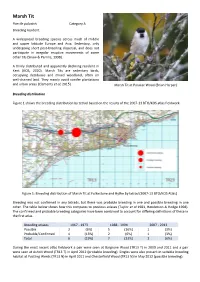

Marsh Tit Poecile Palustris Category a Breeding Resident

Marsh Tit Poecile palustris Category A Breeding resident. A widespread breeding species across much of middle and upper latitude Europe and Asia. Sedentary, only undergoing short post-breeding dispersal, and does not participate in irregular eruptive movements of some other tits (Snow & Perrins, 1998). A thinly distributed and apparently declining resident in Kent (KOS, 2020). Marsh Tits are sedentary birds, occupying deciduous and mixed woodland, often on well-drained land. They mainly avoid conifer plantations and urban areas (Clements et al, 2015). Marsh Tit at Paraker Wood (Brian Harper) Breeding distribution Figure 1 shows the breeding distribution by tetrad based on the results of the 2007-13 BTO/KOS atlas fieldwork. Figure 1: Breeding distribution of Marsh Tit at Folkestone and Hythe by tetrad (2007-13 BTO/KOS Atlas) Breeding was not confirmed in any tetrads, but there was probable breeding in one and possible breeding in one other. The table below shows how this compares to previous atlases (Taylor et al 1981, Henderson & Hodge 1998). The confirmed and probable breeding categories have been combined to account for differing definitions of these in the first atlas. Breeding atlases 1967 - 1973 1988 - 1994 2007 - 2013 Possible 2 (6%) 5 (16%) 1 (3%) Probable/Confirmed 4 (13%) 2 (6%) 1 (3%) Total 6 (19%) 7 (23%) 2 (6%) During the most recent atlas fieldwork a pair were seen at Bargrove Wood (TR13 T) in 2009 and 2011 and a pair were seen at Asholt Wood (TR13 T) in April 2012 (probable breeding). Singles were also present in suitable breeding habitat at Postling Wents (TR13 N) in April 2011 and Chesterfield Wood (TR13 N) in May 2012 (possible breeding). -

Gray-Headed Chickadee Captive Flock and Propagation a Scoping Report

Gray-headed Chickadee Captive Flock and Propagation A Scoping Report Aaron Lang Dr. Rebecca McGuire Wildlife Conservation Society, Arctic Beringia Program 3550 Airport Way, Suite 5 Fairbanks, AK 99709 Photo Credit: Aaron Lang [email protected] A report to the Alaska Department of Fish and Game (ADF&G) in fulfillment of cooperative agreement 19-054 under State Wildlife Grant T-33 Project 10.0, April, 2020. ADF&G and the Wildlife Conservation Society have co-ownership of all content. Recommended Citation: McGuire, R. 2020. Gray-headed Chickadee captive flock and propagation: A scoping report. A report by the Wildlife Conservation Society to the Alaska Department of Fish and Game, in fulfillment of cooperative agreement 19-054, Fairbanks. Table of Contents 1.0 INTRODUCTION ..................................................................................................................... 1 2.0 TRIGGERS FOR MOVING FORWARD ................................................................................ 2 3.0 REVIEW OF SELECT (PRIMARY) LOCATIONS OF CAPTIVE CHICKADEES OR SIMILAR SPECIES ........................................................................................................................ 3 4.0 GENERAL REQUIREMENTS OF A CAPTIVE FLOCK FACILITY, INCLUDING CAPTIVE PROPAGATION ........................................................................................................... 7 5.0 OPTIONS FOR LOCATION OF CAPTIVE HOUSING ....................................................... 14 6.0 INITIAL STOCKING ............................................................................................................ -

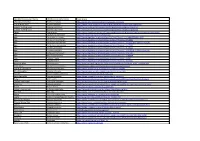

The PDF, Here, Is a Full List of All Mentioned

FAUNA Vernacular Name FAUNA Scientific Name Read more a European Hoverfly Pocota personata https://www.naturespot.org.uk/species/pocota-personata a small black wasp Stigmus pendulus https://www.bwars.com/wasp/crabronidae/pemphredoninae/stigmus-pendulus a spider-hunting wasp Anoplius concinnus https://www.bwars.com/wasp/pompilidae/pompilinae/anoplius-concinnus a spider-hunting wasp Anoplius nigerrimus https://www.bwars.com/wasp/pompilidae/pompilinae/anoplius-nigerrimus Adder Vipera berus https://www.woodlandtrust.org.uk/trees-woods-and-wildlife/animals/reptiles-and-amphibians/adder/ Alga Cladophora glomerata https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cladophora Alga Closterium acerosum https://www.algaebase.org/search/species/detail/?species_id=x44d373af81fe4f72 Alga Closterium ehrenbergii https://www.algaebase.org/search/species/detail/?species_id=28183 Alga Closterium moniliferum https://www.algaebase.org/search/species/detail/?species_id=28227&sk=0&from=results Alga Coelastrum microporum https://www.algaebase.org/search/species/detail/?species_id=27402 Alga Cosmarium botrytis https://www.algaebase.org/search/species/detail/?species_id=28326 Alga Lemanea fluviatilis https://www.algaebase.org/search/species/detail/?species_id=32651&sk=0&from=results Alga Pediastrum boryanum https://www.algaebase.org/search/species/detail/?species_id=27507 Alga Stigeoclonium tenue https://www.algaebase.org/search/species/detail/?species_id=60904 Alga Ulothrix zonata https://www.algaebase.org/search/species/detail/?species_id=562 Algae Synedra tenera https://www.algaebase.org/search/species/detail/?species_id=34482 -

Scanning Behaviour and Spatial Niche

Heft 1 ] 73 1992 ] Kurze Mitteilungen J. Orn. 133, 1992: S. 73--77 Scanning Behaviour and Spatial Niche Luis M. Carrascal and Eulalia Moreno Introduction Searching patterns of birds are largely a function of their morphological and perceptual traits. The habitat features which most affect searching and prey-attacking behaviour in forest birds are vegetation structure and the characteristics of the available prey (ROBINSON & HOLMES 1982, CODY 1985, HOLMES& ROBINSON1988). Vegetation structure influences the way in which birds move through the habitat in order to capture prey. At the evolutionary time scale, habitat and prey features act as selective forces which shape a species' foraging style. Such foraging styles or syndromes are the combination of various morphological and behavioural traits that maximize the foraging efficiency of each species in its environment as has been elucidated already in some groups of birds (ROBINSON& HOLMES 1982). Vigilance during feeding has been associated with antipredator defense and/or the acquisi- tion of information from other birds when in aggregations. In small passerine species, the vigilance rate related to predation risk varies with aggregation size, temperature, food handling costs, distance to cover, and exposure to predators (BERNAXD1983, BEVERn)GE& DEAG 1986, GLOCK 1987, HOGSTAD1988. LIMA& DiLL 1990, PIPER 1990). Nevertheless, although vegetation cover has been recognized as a determinant of predation risk, scanning rate, and flocking behaviour, little effort has been devoted to the study of interspecific variation of vigilance behaviour in relation to the spatial niche of individual species. Here we compare the vigilance behaviour of three small tree-gleaning birds in relation to their spatial niche. -

Comparative Analysis of Hissing Calls in Five Tit Species Li Zhang, Jianping Liu, Zezhong Gao, Lei Zhang, Dongmei Wan, Wei Liang, Anders Pape Møller

Comparative analysis of hissing calls in five tit species Li Zhang, Jianping Liu, Zezhong Gao, Lei Zhang, Dongmei Wan, Wei Liang, Anders Pape Møller To cite this version: Li Zhang, Jianping Liu, Zezhong Gao, Lei Zhang, Dongmei Wan, et al.. Comparative analysis of hissing calls in five tit species. Behavioural Processes, Elsevier, 2019. hal-03024634 HAL Id: hal-03024634 https://hal-cnrs.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-03024634 Submitted on 25 Nov 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. 1 Comparative analysis of hissing calls in five tit species 1 2 1 1 1, * 2 Li Zhang , Jianping Liu , Zezhong Gao , Lei Zhang , Dongmei Wan , Wei 2, * 3 3 Liang , Anders Pape Møller 1 4 Key Laboratory of Animal Resource and Epidemic Disease Prevention, 5 College of Life Sciences, Liaoning University, Shenyang 110036, China 2 6 Ministry of Education Key Laboratory for Ecology of Tropical Islands, 7 College of Life Sciences, Hainan Normal University, Haikou 571158, China 3 8 Ecologie Systématique Evolution, Université Paris-Sud, CNRS, 9 AgroParisTech, Université Paris-Saclay, F-91405 Orsay Cedex, France 10 Email address: 11 LZ, [email protected], ID: 0000-0003-1224-7855 12 JL, [email protected], ID: 0000-0001-6526-8831 13 ZG, [email protected] 14 LZ, [email protected], ID: 0000-0003-2328-1194 15 DW, [email protected], ID: 0000-0002-1465-6110 16 WL, [email protected], ID: 0000-0002-0004-9707 17 APM, [email protected], ID: 0000-0003-3739-4675 18 Word count: 4571 19 *Corresponding author.