Comparative Analysis of Hissing Calls in Five Tit Species Li Zhang, Jianping Liu, Zezhong Gao, Lei Zhang, Dongmei Wan, Wei Liang, Anders Pape Møller

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Printable PDF Format

Field Guides Tour Report Taiwan 2020 Feb 1, 2020 to Feb 12, 2020 Phil Gregory & local guide Arco Huang For our tour description, itinerary, past triplists, dates, fees, and more, please VISIT OUR TOUR PAGE. This gorgeous male Swinhoe's Pheasant was one of the birds of the trip! We found a pair of these lovely endemic pheasants at Dasyueshan. Photo by guide Phil Gregory. This was a first run for the newly reactivated Taiwan tour (which we last ran in 2006), with a new local organizer who proved very good and enthusiastic, and knew the best local sites to visit. The weather was remarkably kind to us and we had no significant daytime rain, somewhat to my surprise, whilst temperatures were pretty reasonable even in the mountains- though it was cold at night at Dasyueshan where the unheated hotel was a bit of a shock, but in a great birding spot, so overall it was bearable. Fog on the heights of Hohuanshan was a shame but at least the mid and lower levels stayed clear. Otherwise the lowland sites were all good despite it being very windy at Hengchun in the far south. Arco and I decided to use a varied assortment of local eating places with primarily local menus, and much to my amazement I found myself enjoying noodle dishes. The food was a highlight in fact, as it was varied, often delicious and best of all served quickly whilst being both hot and fresh. A nice adjunct to the trip, and avoided losing lots of time with elaborate meals. -

ED45E Rare and Scarce Species Hierarchy.Pdf

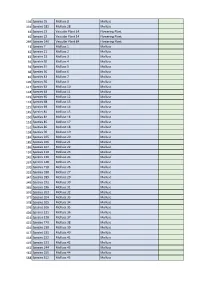

104 Species 55 Mollusc 8 Mollusc 334 Species 181 Mollusc 28 Mollusc 44 Species 23 Vascular Plant 14 Flowering Plant 45 Species 23 Vascular Plant 14 Flowering Plant 269 Species 149 Vascular Plant 84 Flowering Plant 13 Species 7 Mollusc 1 Mollusc 42 Species 21 Mollusc 2 Mollusc 43 Species 22 Mollusc 3 Mollusc 59 Species 30 Mollusc 4 Mollusc 59 Species 31 Mollusc 5 Mollusc 68 Species 36 Mollusc 6 Mollusc 81 Species 43 Mollusc 7 Mollusc 105 Species 56 Mollusc 9 Mollusc 117 Species 63 Mollusc 10 Mollusc 118 Species 64 Mollusc 11 Mollusc 119 Species 65 Mollusc 12 Mollusc 124 Species 68 Mollusc 13 Mollusc 125 Species 69 Mollusc 14 Mollusc 145 Species 81 Mollusc 15 Mollusc 150 Species 84 Mollusc 16 Mollusc 151 Species 85 Mollusc 17 Mollusc 152 Species 86 Mollusc 18 Mollusc 158 Species 90 Mollusc 19 Mollusc 184 Species 105 Mollusc 20 Mollusc 185 Species 106 Mollusc 21 Mollusc 186 Species 107 Mollusc 22 Mollusc 191 Species 110 Mollusc 23 Mollusc 245 Species 136 Mollusc 24 Mollusc 267 Species 148 Mollusc 25 Mollusc 270 Species 150 Mollusc 26 Mollusc 333 Species 180 Mollusc 27 Mollusc 347 Species 189 Mollusc 29 Mollusc 349 Species 191 Mollusc 30 Mollusc 365 Species 196 Mollusc 31 Mollusc 376 Species 203 Mollusc 32 Mollusc 377 Species 204 Mollusc 33 Mollusc 378 Species 205 Mollusc 34 Mollusc 379 Species 206 Mollusc 35 Mollusc 404 Species 221 Mollusc 36 Mollusc 414 Species 228 Mollusc 37 Mollusc 415 Species 229 Mollusc 38 Mollusc 416 Species 230 Mollusc 39 Mollusc 417 Species 231 Mollusc 40 Mollusc 418 Species 232 Mollusc 41 Mollusc 419 Species 233 -

Small Protection Plates Against Marten Predation on Nest Boxes

Appl. Entomol. Zool. 40 (4): 575–577 (2005) http://odokon.ac.affrc.go.jp/ Small protection plates against marten predation on nest boxes Noriyuki YAMAGUCHI,1,*,† Katsura M. KAWANO,1 Yasuhiro YAMAGUCHI2 and Takashi SAITO3 1 Department of Biology, Faculty of Science, Kyushu University; Fukuoka 812–8581, Japan 2 Wildlife Management Laboratory, National Agricultural Research Center; Tsukuba, Ibaraki 305–8666, Japan 3 Yamashina Institute for Ornithology; Abiko, Chiba 270–1145, Japan (Received 27 October 2004; Accepted 3 June 2005) Abstract The nest box is a powerful research tool for ecological and conservational studies of birds and several other cavity nesters. However, skilful predators such as martens sometimes invade nest boxes, thus disturbing researches. To pro- tect nest boxes against predation by martens, we attached a small plate inside the nest box below the entrance hole, and we report here on the advantage of this device. In 1999 and 2000, respectively, 73.0% and 64.8% nest boxes were used by the Great Tit and the Varied Tit. After fitting boxes with the plate in 2000, the percentage of predated nests by martens decreased from 22.4% to 5.9%, and the percentage of successful nests increased from 29.3% to 43.8%. Key words: Marten; nest box; protection against predation (dominant overstory trees are Machilus thunbergii, INTRODUCTION Quercus glauca, Styrax japonica, and Magnolia The nest box is a powerful and popular research obovata), ranging in elevation from 210 m to 380 m tool for ecological and conservational studies. above sea level. Dominant secondary cavity nesters Many researchers commonly use nest boxes, notic- are Varied Tits (Parus varius) and Great Tits ing careful regard to estimate the results that they (Parus major). -

Biodiversity Climate Change Impacts Report Card Technical Paper 12. the Impact of Climate Change on Biological Phenology In

Sparks Pheno logy Biodiversity Report Card paper 12 2015 Biodiversity Climate Change impacts report card technical paper 12. The impact of climate change on biological phenology in the UK Tim Sparks1 & Humphrey Crick2 1 Faculty of Engineering and Computing, Coventry University, Priory Street, Coventry, CV1 5FB 2 Natural England, Eastbrook, Shaftesbury Road, Cambridge, CB2 8DR Email: [email protected]; [email protected] 1 Sparks Pheno logy Biodiversity Report Card paper 12 2015 Executive summary Phenology can be described as the study of the timing of recurring natural events. The UK has a long history of phenological recording, particularly of first and last dates, but systematic national recording schemes are able to provide information on the distributions of events. The majority of data concern spring phenology, autumn phenology is relatively under-recorded. The UK is not usually water-limited in spring and therefore the major driver of the timing of life cycles (phenology) in the UK is temperature [H]. Phenological responses to temperature vary between species [H] but climate change remains the major driver of changed phenology [M]. For some species, other factors may also be important, such as soil biota, nutrients and daylength [M]. Wherever data is collected the majority of evidence suggests that spring events have advanced [H]. Thus, data show advances in the timing of bird spring migration [H], short distance migrants responding more than long-distance migrants [H], of egg laying in birds [H], in the flowering and leafing of plants[H] (although annual species may be more responsive than perennial species [L]), in the emergence dates of various invertebrates (butterflies [H], moths [M], aphids [H], dragonflies [M], hoverflies [L], carabid beetles [M]), in the migration [M] and breeding [M] of amphibians, in the fruiting of spring fungi [M], in freshwater fish migration [L] and spawning [L], in freshwater plankton [M], in the breeding activity among ruminant mammals [L] and the questing behaviour of ticks [L]. -

Natural History of Japanese Birds

Natural History of Japanese Birds Hiroyoshi Higuchi English text translated by Reiko Kurosawa HEIBONSHA 1 Copyright © 2014 by Hiroyoshi Higuchi, Reiko Kurosawa Typeset and designed by: Washisu Design Office Printed in Japan Heibonsha Limited, Publishers 3-29 Kanda Jimbocho, Chiyoda-ku Tokyo 101-0051 Japan All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means without permission in writing from the publisher. The English text can be downloaded from the following website for free. http://www.heibonsha.co.jp/ 2 CONTENTS Chapter 1 The natural environment and birds of Japan 6 Chapter 2 Representative birds of Japan 11 Chapter 3 Abundant varieties of forest birds and water birds 13 Chapter 4 Four seasons of the satoyama 17 Chapter 5 Active life of urban birds 20 Chapter 6 Interesting ecological behavior of birds 24 Chapter 7 Bird migration — from where to where 28 Chapter 8 The present state of Japanese birds and their future 34 3 Natural History of Japanese Birds Preface [BOOK p.3] Japan is a beautiful country. The hills and dales are covered “satoyama”. When horsetail shoots come out and violets and with rich forest green, the river waters run clear and the moun- cherry blossoms bloom in spring, birds begin to sing and get tain ranges in the distance look hazy purple, which perfectly ready for reproduction. Summer visitors also start arriving in fits a Japanese expression of “Sanshi-suimei (purple mountains Japan one after another from the tropical regions to brighten and clear waters)”, describing great natural beauty. -

GRUNDSTEN Japan 0102 2016

Birding Japan (M. Grundsten, Sweden) 2016 Japan, January 30th - February 14th 2016 Karuizawa – E Hokkaido – S Kyushu – Okinawa – Hachijo-jima Front cover Harlequin Duck Histrionicus histrionicus, common along eastern Hokkaido coasts. Photo: Måns Grundsten Participants Måns Grundsten ([email protected], compiler, most photos), Mattias Andersson, Mattias Gerdin, Sweden. Highlights • A shy Solitary Snipe in the main stream at Karuizawa. • Huge-billed Japanese Grosbeaks and a neat 'griseiventris' Eurasian Bullfinch at Karuizawa. • A single Rustic Bunting behind 7/Eleven at Karuizawa. • Amazing auks from the Oarai-Tomakomai ferry. Impressive numbers of Rhinoceros Auklet! • Parakeet Auklet fly-bys. • Blakiston's Fish Owl in orderly fashion at Rausu. • Displaying Black Scoters at Notsuke peninsula. • Majestic Steller's Sea Eagles in hundreds. • Winter gulls at Hokkaido. • Finding a vagrant Golden-crowned Sparrow at Kiritappu at the same feeders as Asian Rosy Finches. • No less than 48(!) Rock Sandpipers. • A lone immature Red-faced Cormorants on cliffs at Cape Nosappu. • A pair of Ural Owls on day roost at Kushiro. • Feeding Ryukyu Minivets at Lake Mi-ike. • Fifteen thousand plus cranes at Arasaki. • Unexpectedly productive Kogawa Dam – Long-billed Plover. • Saunders's Gulls at Yatsushiro. • Kin Ricefields on Okinawa, easy birding, lots of birds, odd-placed Tundra Bean Geese. • Okinawa Woodpecker and Rail within an hour close to Fushigawa Dam, Yanbaru. • Whistling Green Pigeon eating fruits in Ada Village. • Vocal Ryukyu Robins. • Good shorebird diversity in Naha. • Male Izu Thrush during a short break on Hachijo-jima. • Triple Albatrosses! • Bulwer's Petrel close to the ship. Planning the trip – Future aspects When planning a birding trip to Japan there is a lot of consideration to be made. -

Sri Lanka: January 2015

Tropical Birding Trip Report Sri Lanka: January 2015 A Tropical Birding CUSTOM tour SRI LANKA: Ceylon Sojourn 9th- 23rd January 2015 Tour Leaders: Sam Woods & Chaminda Dilruk SRI LANKA JUNGLEFOWL is Sri Lanka’s colorful national bird, which was ranked among the top five birds of the tour by the group. All photos in this report were taken by Sam Woods. 1 www.tropicalbirding.com +1-409-515-0514 [email protected] Page Tropical Birding Trip Report Sri Lanka: January 2015 INTRODUCTION In many ways Sri Lanka covers it all; for the serious birder, even those with experience from elsewhere in the Indian subcontinent, it offers up a healthy batch of at least 32 endemic bird species (this list continues to grow, though, so could increase further yet); for those without any previous experience of the subcontinent it offers these but, being an island of limited diversity, not the overwhelming numbers of birds, which can be intimidating for the first timer; and for those with a natural history slant that extends beyond the avian, there is plentiful other wildlife besides, to keep all happy, such as endemic monkeys, strange reptiles only found on this teardrop-shaped island, and a bounty of butterflies, which feature day-in, day-out. It should also be made clear that while it appears like a chunk of India which has dropped of the main subcontinent, to frame it, as merely an extension of India, would be a grave injustice, as Sri Lanka feels, looks, and even tastes very different. There are some cultural quirks that make India itself, sometimes challenging to visit for the westerner. -

Best of the Baltic - Bird List - July 2019 Note: *Species Are Listed in Order of First Seeing Them ** H = Heard Only

Best of the Baltic - Bird List - July 2019 Note: *Species are listed in order of first seeing them ** H = Heard Only July 6th 7th 8th 9th 10th 11th 12th 13th 14th 15th 16th 17th Mute Swan Cygnus olor X X X X X X X X Whopper Swan Cygnus cygnus X X X X Greylag Goose Anser anser X X X X X Barnacle Goose Branta leucopsis X X X Tufted Duck Aythya fuligula X X X X Common Eider Somateria mollissima X X X X X X X X Common Goldeneye Bucephala clangula X X X X X X Red-breasted Merganser Mergus serrator X X X X X Great Cormorant Phalacrocorax carbo X X X X X X X X X X Grey Heron Ardea cinerea X X X X X X X X X Western Marsh Harrier Circus aeruginosus X X X X White-tailed Eagle Haliaeetus albicilla X X X X Eurasian Coot Fulica atra X X X X X X X X Eurasian Oystercatcher Haematopus ostralegus X X X X X X X Black-headed Gull Chroicocephalus ridibundus X X X X X X X X X X X X European Herring Gull Larus argentatus X X X X X X X X X X X X Lesser Black-backed Gull Larus fuscus X X X X X X X X X X X X Great Black-backed Gull Larus marinus X X X X X X X X X X X X Common/Mew Gull Larus canus X X X X X X X X X X X X Common Tern Sterna hirundo X X X X X X X X X X X X Arctic Tern Sterna paradisaea X X X X X X X Feral Pigeon ( Rock) Columba livia X X X X X X X X X X X X Common Wood Pigeon Columba palumbus X X X X X X X X X X X Eurasian Collared Dove Streptopelia decaocto X X X Common Swift Apus apus X X X X X X X X X X X X Barn Swallow Hirundo rustica X X X X X X X X X X X Common House Martin Delichon urbicum X X X X X X X X White Wagtail Motacilla alba X X -

DNA Barcoding Reveals 24 Distinct Lineages As Cryptic Bird Species Candidates in and Around the Japanese Archipelago

Molecular Ecology Resources (2015) 15, 177–186 doi: 10.1111/1755-0998.12282 DNA barcoding reveals 24 distinct lineages as cryptic bird species candidates in and around the Japanese Archipelago TAKEMA SAITOH,*1 NORIMASA SUGITA,†1 SAYAKA SOMEYA,† YASUKO IWAMI,*† SAYAKA KOBAYASHI,* HIROMI KAMIGAICHI,† AKI HIGUCHI,† SHIGEKI ASAI,* YOSHIHIRO YAMAMOTO* and ISAO NISHIUMI† *Division of Natural History, Yamashina Institute for Ornithology, 115 Konoyama, Abiko, Chiba 270-1145, Japan, †Department of Zoology, National Museum of Nature and Science, Amakubo 4-1-1, Tsukuba, Ibaraki 305-0005, Japan Abstract DNA barcoding using a partial region (648 bp) of the cytochrome c oxidase I (COI) gene is a powerful tool for species identification and has revealed many cryptic species in various animal taxa. In birds, cryptic species are likely to occur in insular regions like the Japanese Archipelago due to the prevention of gene flow by sea barriers. Using COI sequences of 234 of the 251 Japanese-breeding bird species, we established a DNA barcoding library for species identification and estimated the number of cryptic species candidates. A total of 226 species (96.6%) had unique COI sequences with large genetic divergence among the closest species based on neighbour-joining clusters, genetic dis- tance criterion and diagnostic substitutions. Eleven cryptic species candidates were detected, with distinct intraspe- cific deep genetic divergences, nine lineages of which were geographically separated by islands and straits within the Japanese Archipelago. To identify Japan-specific cryptic species from trans-Paleartic birds, we investigated the genetic structure of 142 shared species over an extended region covering Japan and Eurasia; 19 of these species formed two or more clades with high bootstrap values. -

Habitat Modelling and the Ecology of the Marsh Tit (Poecile Palustris)

HABITAT MODELLING AND THE ECOLOGY OF THE MARSH TIT (POECILE PALUSTRIS) RICHARD K BROUGHTON A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of Bournemouth University for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy August 2012 Bournemouth University in collaboration with the Centre for Ecology & Hydrology This copy of the thesis has been supplied on condition that anyone who consults it is understood to recognise that its copyright rests with its author and due acknowledgement must always be made of the use of any material contained in, or derived from, this thesis. 2 ABSTRACT Richard K Broughton Habitat modelling and the ecology of the Marsh Tit (Poecile palustris) Among British birds, a number of woodland specialists have undergone a serious population decline in recent decades, for reasons that are poorly understood. The Marsh Tit is one such species, experiencing a 71% decline in abundance between 1967 and 2009, and a 17% range contraction between 1968 and 1991. The factors driving this decline are uncertain, but hypotheses include a reduction in breeding success and annual survival, increased inter-specific competition, and deteriorating habitat quality. Despite recent work investigating some of these elements, knowledge of the Marsh Tit’s behaviour, landscape ecology and habitat selection remains incomplete, limiting the understanding of the species’ decline. This thesis provides additional key information on the ecology of the Marsh Tit with which to test and review leading hypotheses for the species’ decline. Using novel analytical methods, comprehensive high-resolution models of woodland habitat derived from airborne remote sensing were combined with extensive datasets of Marsh Tit territory and nest-site locations to describe habitat selection in unprecedented detail. -

Egg Recognition in Cinereous Tits (Parus Cinereus): Eggshell Spots Matter Jianping Liu1 , Canchao Yang1 , Jiangping Yu2,3 , Haitao Wang2,4 and Wei Liang1*

Liu et al. Avian Res (2019) 10:37 https://doi.org/10.1186/s40657-019-0178-1 Avian Research RESEARCH Open Access Egg recognition in Cinereous Tits (Parus cinereus): eggshell spots matter Jianping Liu1 , Canchao Yang1 , Jiangping Yu2,3 , Haitao Wang2,4 and Wei Liang1* Abstract Background: Brood parasitic birds such as cuckoos (Cuculus spp.) can reduce their host’s reproductive success. Such selection pressure on the hosts has driven the evolution of defense behaviors such as egg rejection against cuckoo parasitism. Studies have shown that Cinereous Tits (Parus cinereus) in China have a good ability for recognizing foreign eggs. However, it is unclear whether egg spots play a role in egg recognition. The aims of our study were to inves- tigate the egg recognition ability of two Cinereous Tit populations in China and to explore the role of spots in egg recognition. Methods: To test the efect of eggshell spots on egg recognition, pure white eggs of the White-rumped Munia (Lon- chura striata) and eggs of White-rumped Munia painted with red brown spots were used to simulate experimental parasitism. Results: Egg experiments showed that Cinereous Tits rejected 51.5% of pure white eggs of the White-rumped Munia, but only 14.3% of spotted eggs of the White-rumped Munia. There was a signifcant diference in egg recognition and rejection rate between the two egg types. Conclusions: We conclude that eggshell spots on Cinereous Tit eggs had a signaling function and may be essential to tits for recognizing and rejecting parasitic eggs. Keywords: Brood parasitism, Egg recognition, Egg rejection, Eggshell spots, Parus cinereus Background egg rejection by hosts, many parasitic birds evolve coun- Te mutual adaptations and counter-defense strategies ter-adaptations to overcome the hosts’ defenses by laying between brood parasitic birds such as cuckoos (Cuculus mimicking (Brooke and Davies 1988; Avilés et al. -

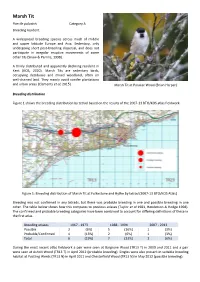

Marsh Tit Poecile Palustris Category a Breeding Resident

Marsh Tit Poecile palustris Category A Breeding resident. A widespread breeding species across much of middle and upper latitude Europe and Asia. Sedentary, only undergoing short post-breeding dispersal, and does not participate in irregular eruptive movements of some other tits (Snow & Perrins, 1998). A thinly distributed and apparently declining resident in Kent (KOS, 2020). Marsh Tits are sedentary birds, occupying deciduous and mixed woodland, often on well-drained land. They mainly avoid conifer plantations and urban areas (Clements et al, 2015). Marsh Tit at Paraker Wood (Brian Harper) Breeding distribution Figure 1 shows the breeding distribution by tetrad based on the results of the 2007-13 BTO/KOS atlas fieldwork. Figure 1: Breeding distribution of Marsh Tit at Folkestone and Hythe by tetrad (2007-13 BTO/KOS Atlas) Breeding was not confirmed in any tetrads, but there was probable breeding in one and possible breeding in one other. The table below shows how this compares to previous atlases (Taylor et al 1981, Henderson & Hodge 1998). The confirmed and probable breeding categories have been combined to account for differing definitions of these in the first atlas. Breeding atlases 1967 - 1973 1988 - 1994 2007 - 2013 Possible 2 (6%) 5 (16%) 1 (3%) Probable/Confirmed 4 (13%) 2 (6%) 1 (3%) Total 6 (19%) 7 (23%) 2 (6%) During the most recent atlas fieldwork a pair were seen at Bargrove Wood (TR13 T) in 2009 and 2011 and a pair were seen at Asholt Wood (TR13 T) in April 2012 (probable breeding). Singles were also present in suitable breeding habitat at Postling Wents (TR13 N) in April 2011 and Chesterfield Wood (TR13 N) in May 2012 (possible breeding).