Are Tits Really Unsuitable Hosts for the Common Cuckoo?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

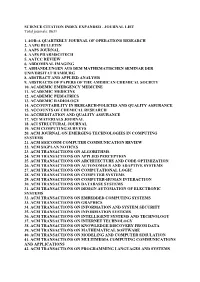

SCIENCE CITATION INDEX EXPANDED - JOURNAL LIST Total Journals: 8631

SCIENCE CITATION INDEX EXPANDED - JOURNAL LIST Total journals: 8631 1. 4OR-A QUARTERLY JOURNAL OF OPERATIONS RESEARCH 2. AAPG BULLETIN 3. AAPS JOURNAL 4. AAPS PHARMSCITECH 5. AATCC REVIEW 6. ABDOMINAL IMAGING 7. ABHANDLUNGEN AUS DEM MATHEMATISCHEN SEMINAR DER UNIVERSITAT HAMBURG 8. ABSTRACT AND APPLIED ANALYSIS 9. ABSTRACTS OF PAPERS OF THE AMERICAN CHEMICAL SOCIETY 10. ACADEMIC EMERGENCY MEDICINE 11. ACADEMIC MEDICINE 12. ACADEMIC PEDIATRICS 13. ACADEMIC RADIOLOGY 14. ACCOUNTABILITY IN RESEARCH-POLICIES AND QUALITY ASSURANCE 15. ACCOUNTS OF CHEMICAL RESEARCH 16. ACCREDITATION AND QUALITY ASSURANCE 17. ACI MATERIALS JOURNAL 18. ACI STRUCTURAL JOURNAL 19. ACM COMPUTING SURVEYS 20. ACM JOURNAL ON EMERGING TECHNOLOGIES IN COMPUTING SYSTEMS 21. ACM SIGCOMM COMPUTER COMMUNICATION REVIEW 22. ACM SIGPLAN NOTICES 23. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON ALGORITHMS 24. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON APPLIED PERCEPTION 25. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON ARCHITECTURE AND CODE OPTIMIZATION 26. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON AUTONOMOUS AND ADAPTIVE SYSTEMS 27. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON COMPUTATIONAL LOGIC 28. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON COMPUTER SYSTEMS 29. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON COMPUTER-HUMAN INTERACTION 30. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON DATABASE SYSTEMS 31. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON DESIGN AUTOMATION OF ELECTRONIC SYSTEMS 32. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON EMBEDDED COMPUTING SYSTEMS 33. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON GRAPHICS 34. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON INFORMATION AND SYSTEM SECURITY 35. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON INFORMATION SYSTEMS 36. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON INTELLIGENT SYSTEMS AND TECHNOLOGY 37. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON INTERNET TECHNOLOGY 38. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON KNOWLEDGE DISCOVERY FROM DATA 39. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON MATHEMATICAL SOFTWARE 40. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON MODELING AND COMPUTER SIMULATION 41. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON MULTIMEDIA COMPUTING COMMUNICATIONS AND APPLICATIONS 42. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON PROGRAMMING LANGUAGES AND SYSTEMS 43. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON RECONFIGURABLE TECHNOLOGY AND SYSTEMS 44. -

2018 Journal Citation Reports Journals in the 2018 Release of JCR 2 Journals in the 2018 Release of JCR

2018 Journal Citation Reports Journals in the 2018 release of JCR 2 Journals in the 2018 release of JCR Abbreviated Title Full Title Country/Region SCIE SSCI 2D MATER 2D MATERIALS England ✓ 3 BIOTECH 3 BIOTECH Germany ✓ 3D PRINT ADDIT MANUF 3D PRINTING AND ADDITIVE MANUFACTURING United States ✓ 4OR-A QUARTERLY JOURNAL OF 4OR-Q J OPER RES OPERATIONS RESEARCH Germany ✓ AAPG BULL AAPG BULLETIN United States ✓ AAPS J AAPS JOURNAL United States ✓ AAPS PHARMSCITECH AAPS PHARMSCITECH United States ✓ AATCC J RES AATCC JOURNAL OF RESEARCH United States ✓ AATCC REV AATCC REVIEW United States ✓ ABACUS-A JOURNAL OF ACCOUNTING ABACUS FINANCE AND BUSINESS STUDIES Australia ✓ ABDOM IMAGING ABDOMINAL IMAGING United States ✓ ABDOM RADIOL ABDOMINAL RADIOLOGY United States ✓ ABHANDLUNGEN AUS DEM MATHEMATISCHEN ABH MATH SEM HAMBURG SEMINAR DER UNIVERSITAT HAMBURG Germany ✓ ACADEMIA-REVISTA LATINOAMERICANA ACAD-REV LATINOAM AD DE ADMINISTRACION Colombia ✓ ACAD EMERG MED ACADEMIC EMERGENCY MEDICINE United States ✓ ACAD MED ACADEMIC MEDICINE United States ✓ ACAD PEDIATR ACADEMIC PEDIATRICS United States ✓ ACAD PSYCHIATR ACADEMIC PSYCHIATRY United States ✓ ACAD RADIOL ACADEMIC RADIOLOGY United States ✓ ACAD MANAG ANN ACADEMY OF MANAGEMENT ANNALS United States ✓ ACAD MANAGE J ACADEMY OF MANAGEMENT JOURNAL United States ✓ ACAD MANAG LEARN EDU ACADEMY OF MANAGEMENT LEARNING & EDUCATION United States ✓ ACAD MANAGE PERSPECT ACADEMY OF MANAGEMENT PERSPECTIVES United States ✓ ACAD MANAGE REV ACADEMY OF MANAGEMENT REVIEW United States ✓ ACAROLOGIA ACAROLOGIA France ✓ -

Journal Impact Factor 2007

Journal Impact Factor 2007 Number Journal Name ISSN Impact 1 AAPG BULLETIN 0149-1423 01.273 2 AAPS Journal 1550-7416 03.756 3 AAPS PHARMSCITECH 1530-9932 01.351 4 AATCC REVIEW 1532-8813 00.478 5 ABDOMINAL IMAGING 0942-8925 01.213 ABHANDLUNGEN AUS DEM MATHEMATISCHEN SEMINAR DER UNIVERSITAT 6 HAMBURG 0025-5858 00.118 7 Abstract and Applied Analysis 1085-3375 00.163 8 ACADEMIC EMERGENCY MEDICINE 1069-6563 01.990 9 ACADEMIC MEDICINE 1040-2446 02.571 10 ACADEMIC RADIOLOGY 1076-6332 02.094 11 ACCOUNTS OF CHEMICAL RESEARCH 0001-4842 16.214 12 ACCREDITATION AND QUALITY ASSURANCE 0949-1775 00.717 13 ACI MATERIALS JOURNAL 0889-325X 00.670 14 ACI STRUCTURAL JOURNAL 0889-3241 00.665 15 ACM COMPUTING SURVEYS 0360-0300 05.250 16 ACM SIGPLAN NOTICES 0362-1340 00.108 17 ACM TRANSACTIONS ON COMPUTER SYSTEMS 0734-2071 01.917 18 ACM TRANSACTIONS ON DATABASE SYSTEMS 0362-5915 02.078 19 ACM TRANSACTIONS ON DESIGN AUTOMATION OF ELECTRONIC SYSTEMS 1084-4309 00.573 20 ACM TRANSACTIONS ON GRAPHICS 0730-0301 03.413 21 ACM TRANSACTIONS ON INFORMATION SYSTEMS 1046-8188 01.969 22 ACM TRANSACTIONS ON MATHEMATICAL SOFTWARE 0098-3500 01.714 23 ACM TRANSACTIONS ON PROGRAMMING LANGUAGES AND SYSTEMS 0164-0925 01.220 24 ACM TRANSACTIONS ON SOFTWARE ENGINEERING AND METHODOLOGY 1049-331X 02.792 25 ACOUSTICAL PHYSICS 1063-7710 00.416 26 ACOUSTICS RESEARCH LETTERS ONLINE-ARLO 1529-7853 01.083 27 ACS Chemical Biology 1554-8929 04.741 28 ACS Nano 1936-0851 29 ACSMS HEALTH & FITNESS JOURNAL 1091-5397 00.082 30 ACTA ACUSTICA UNITED WITH ACUSTICA 1610-1928 00.707 31 ACTA AGRICULTURAE -

Journal Impact Factor (JCR 2018)

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/323571463 2018 Journal Impact Factor (JCR 2018) Technical Report · March 2018 CITATIONS READS 0 36,968 1 author: Chunbiao Zhu Peking University 21 PUBLICATIONS 35 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects: Robust Saliency Detection via Fusing Foreground and Background Priors View project A Multilayer Backpropagation Saliency Detection Algorithm Based on Depth Mining View project All content following this page was uploaded by Chunbiao Zhu on 27 June 2018. The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file. Journal Data Filtered By: Selected JCR Year: 2017 Selected Editions: SCIE,SSCI Selected Category Scheme: WoS Journal Eigenfactor Rank Full Journal Title Total Cites Impact Score 1 CA-A CANCER JOURNAL FOR CLINICIANS 28,839 244.585 0.066030 2 NEW ENGLAND JOURNAL OF MEDICINE 332,830 79.258 0.702000 3 LANCET 233,269 53.254 0.435740 4 CHEMICAL REVIEWS 174,920 52.613 0.265650 5 Nature Reviews Materials 3,218 51.941 0.015060 6 NATURE REVIEWS DRUG DISCOVERY 31,312 50.167 0.054410 7 JAMA-JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN MEDICAL ASSOCIATION 148,774 47.661 0.299960 8 Nature Energy 5,072 46.859 0.020430 9 NATURE REVIEWS CANCER 50,407 42.784 0.079730 10 NATURE REVIEWS IMMUNOLOGY 39,215 41.982 0.085360 11 NATURE 710,766 41.577 1.355810 12 NATURE REVIEWS GENETICS 35,680 41.465 0.094300 13 SCIENCE 645,132 41.058 1.127160 14 CHEMICAL SOCIETY REVIEWS 125,900 40.182 0.275690 15 NATURE MATERIALS -

Copies of Journal Articles Offered by Wfvz

The Condor 95:495-496 0 The Cooper Ornithological Society 1993 COPIES OF JOURNAL ARTICLES OFFERED BY WFVZ The Western Foundation of Vertebrate Zoology main- Bulletin of the Oklahoma OrnithologicalSociety tains one of the largest ornithological libraries in the Bulletin df the Oriental Bird Club - United States.As a courtesyto Cooper Ornithological Bulletin of the Texas OrnitholopicalSocietv Society members, the foundation provides free pho- Bulletin if the World Working croup on B&ds of Prey tocopies of articles from journals that are not widely and Owls available.The foundation welcomestax deductiblegifts C.F.O. Journal of unneededjournals and books. Present WFVZ jour- Calidris nal holdings include complete or significantruns of the Cassinia following journals: Centzontle Chat A.F.A. Watchbird Ciconia ACTA Ornithologica Colonial Waterbird SocietvBulletin ACTA OrnithologicaLituanica Colonial Waterbirds i Alabama Birdlife Communicationsof theBaltic Commissionfor the Study Alauda of Bird Migration American Birds Condor AngewandteOrnithologie ConnecticutWarbler Anser Corax Anuari Ornitologicde les Balears Corella Aquila Cormorant Ararajuba Current Ornithology Ardea Cyanopica Ardeola Dansk OrnithologiskForenings Tidsskrift Audubon Dutch Birding Auk Egretta Australian Aviculture Elepaio Australian Bird Watcher Emu Australian Birds Evas Aves Fhlke AviculturalMagazine Florida Field Naturalist Avocetta Florida Naturalist Babbler Forktail Beitraegezur Vogelkunde Gabar Bird Behaviour Garcilla Bird Conservation GerfautlGiervalk Bird ConservationInternational -

Rank Full Journal Title Journal Impact Factor 1 CA-A CANCER

Journal Data Filtered By: Selected JCR Year: 2019 Selected Editions: SCIE,SSCI Selected Category Scheme: WoS Journal Impact Rank Full Journal Title Factor 1 CA-A CANCER JOURNAL FOR CLINICIANS 292.278 2 NEW ENGLAND JOURNAL OF MEDICINE 74.699 3 Nature Reviews Materials 71.189 4 NATURE REVIEWS DRUG DISCOVERY 64.797 5 LANCET 60.392 6 WHO Technical Report Series 59.000 7 NATURE REVIEWS MOLECULAR CELL BIOLOGY 55.470 8 Nature Reviews Clinical Oncology 53.276 9 NATURE REVIEWS CANCER 53.030 10 CHEMICAL REVIEWS 52.758 11 Nature Energy 46.495 12 JAMA-JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN MEDICAL ASSOCIATION 45.540 13 REVIEWS OF MODERN PHYSICS 45.037 14 CHEMICAL SOCIETY REVIEWS 42.846 15 NATURE 42.778 16 SCIENCE 41.845 17 Nature Reviews Disease Primers 40.689 18 World Psychiatry 40.595 18 World Psychiatry 40.595 20 NATURE REVIEWS IMMUNOLOGY 40.358 21 NATURE MATERIALS 38.663 22 CELL 38.637 23 NATURE BIOTECHNOLOGY 36.558 24 NATURE MEDICINE 36.130 25 Living Reviews in Relativity 35.429 26 Nature Reviews Chemistry 34.953 27 NATURE REVIEWS MICROBIOLOGY 34.209 28 LANCET ONCOLOGY 33.752 29 NATURE REVIEWS NEUROSCIENCE 33.654 30 NATURE REVIEWS GENETICS 33.133 31 Annual Review of Astronomy and Astrophysics 32.963 32 JOURNAL OF CLINICAL ONCOLOGY 32.956 33 PROGRESS IN MATERIALS SCIENCE 31.560 34 Nature Nanotechnology 31.538 35 Nature Photonics 31.241 36 NATURE METHODS 30.822 37 Nature Catalysis 30.471 38 Energy & Environmental Science 30.289 39 BMJ-British Medical Journal 30.223 40 LANCET NEUROLOGY 30.039 41 Nature Reviews Gastroenterology & Hepatology 29.848 42 Cancer Discovery -

2017 Latest Impact Factors (2016 Journal Citation Reports, Thomson Reuters)

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/317639994 2017 Latest Impact Factors (2016 Journal Citation Reports, Thomson Reuters) Research · June 2017 CITATIONS READS 0 23,550 1 author: Anket Sharma Guru Nanak Dev University 42 PUBLICATIONS 34 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects: Brassinosteroids and Abiotic Stress management in Plants View project 24-epibrassinolide regulated detoxification of imidacloprid in Brassica juncea L. View project All content following this page was uploaded by Anket Sharma on 17 June 2017. The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file. Journal Data Filtered By: Selected JCR Year: 2016 Selected Editions: SCIE,SSCI Selected Category Scheme: WoS Journal Impact Rank Full Journal Title Total Cites Eigenfactor Score Factor 1 CA-A CANCER JOURNAL FOR CLINICIANS 24,539 187.040 0.064590 2 NEW ENGLAND JOURNAL OF MEDICINE 315,143 72.406 0.700770 3 NATURE REVIEWS DRUG DISCOVERY 28,750 57.000 0.060820 4 CHEMICAL REVIEWS 159,155 47.928 0.246600 5 LANCET 214,732 47.831 0.404930 6 NATURE REVIEWS MOLECULAR CELL BIOLOGY40,565 46.602 0.095760 7 JAMA-JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN MEDICAL141,015 ASSOCIATION44.405 0.280910 8 NATURE BIOTECHNOLOGY 53,992 41.667 0.169930 9 NATURE REVIEWS GENETICS 32,654 40.282 0.102540 10 NATURE 671,254 40.137 1.433990 11 NATURE REVIEWS IMMUNOLOGY 34,948 39.932 0.093010 12 NATURE MATERIALS 81,831 39.737 0.204020 13 Nature Nanotechnology 48,814 38.986 0.172520 14 -

Journal Data Filtered By: Selected JCR Year: 1997 Selected Editions: SCIE,SSCI Selected Category Scheme: Wos

Journal Data Filtered By: Selected JCR Year: 1997 Selected Editions: SCIE,SSCI Selected Category Scheme: WoS Journal N Full Journal Title ISSN Impact Factor 1 AAPG BULLETIN-AMERICAN ASSOCIATION OF PETROLEUM GEOLOGISTS 0149-1423 1.303 2 ABA JOURNAL 0747-0088 0.279 3 ABDOMINAL IMAGING 0942-8925 0.617 4 ABHANDLUNGEN AUS DEM MATHEMATISCHEN SEMINAR DER UNIVERSITAT HAMBURG 0025-5858 0.241 5 ACADEME-BULLETIN OF THE AAUP 0190-2946 0.274 6 ACADEMIC EMERGENCY MEDICINE 1069-6563 1.042 7 ACADEMIC MEDICINE 1040-2446 1.033 8 ACADEMIC PSYCHIATRY 1042-9670 0.420 9 ACADEMIC RADIOLOGY 1076-6332 0.505 10 ACADEMY OF MANAGEMENT JOURNAL 0001-4273 2.526 11 ACADEMY OF MANAGEMENT REVIEW 0363-7425 2.643 12 ACAROLOGIA 0044-586X 0.178 13 ACCIDENT ANALYSIS AND PREVENTION 0001-4575 0.598 14 ACCOUNTING ORGANIZATIONS AND SOCIETY 0361-3682 0.597 15 ACCOUNTING REVIEW 0001-4826 0.912 16 ACCOUNTS OF CHEMICAL RESEARCH 0001-4842 14.045 17 ACI MATERIALS JOURNAL 0889-325X 0.462 18 ACI STRUCTURAL JOURNAL 0889-3241 0.392 19 ACM COMPUTING SURVEYS 0360-0300 0.218 20 ACM SIGPLAN NOTICES 0362-1340 0.180 21 ACM TRANSACTIONS ON COMPUTER SYSTEMS 0734-2071 1.160 22 ACM TRANSACTIONS ON DATABASE SYSTEMS 0362-5915 0.423 23 ACM TRANSACTIONS ON GRAPHICS 0730-0301 0.828 24 ACM TRANSACTIONS ON INFORMATION SYSTEMS 1046-8188 0.781 25 ACM TRANSACTIONS ON MATHEMATICAL SOFTWARE 0098-3500 0.557 26 ACM TRANSACTIONS ON PROGRAMMING LANGUAGES AND SYSTEMS 0164-0925 0.594 27 ACOUSTICAL PHYSICS 1063-7710 0.085 28 ACP-APPLIED CARDIOPULMONARY PATHOPHYSIOLOGY 0920-5268 0.289 29 ACS SYMPOSIUM SERIES 0097-6156 -

Clarivate Analytics | Journal Citation Reports | Thomson Reuters)

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/325999252 2018 latest Impact Factors (Clarivate Analytics | Journal Citation Reports | Thomson Reuters) Technical Report · June 2018 CITATIONS 0 2 authors, including: Muhammad Umair Quaid-i-Azam University 44 PUBLICATIONS 31 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects: Muscular Dystrophies View project Computational and Genetic analysis of Human inherited diseases View project All content following this page was uploaded by Muhammad Umair on 26 June 2018. The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file. Journal Data Filtered By: Selected JCR Year: 2017 Selected Editions: SCIE,SSCI Selected Category Scheme: WoS Rank Full Journal Title Total Cites Journal Impact Factor Eigenfactor Score 1 CA-A CANCER JOURNAL FOR CLINICIANS 28,839 244.585 0.066030 2 NEW ENGLAND JOURNAL OF MEDICINE 332,830 79.258 0.702000 3 LANCET 233,269 53.254 0.435740 4 CHEMICAL REVIEWS 174,920 52.613 0.265650 5 Nature Reviews Materials 3,218 51.941 0.015060 6 NATURE REVIEWS DRUG DISCOVERY 31,312 50.167 0.054410 JAMA-JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN MEDICAL 7 148,774 47.661 0.299960 ASSOCIATION 8 Nature Energy 5,072 46.859 0.020430 9 NATURE REVIEWS CANCER 50,407 42.784 0.079730 10 NATURE REVIEWS IMMUNOLOGY 39,215 41.982 0.085360 11 NATURE 710,766 41.577 1.355810 12 NATURE REVIEWS GENETICS 35,680 41.465 0.094300 13 SCIENCE 645,132 41.058 1.127160 14 CHEMICAL SOCIETY REVIEWS 125,900 40.182 0.275690 15 NATURE -

Web of Science® Science Citation Index Expandedtm 2012 March Web of Science®

REUTERS/Morteza Nikoubazl SOURCE PUBLICATION LIST FOR WEB OF SCIENCE® SCIENCE CITATION INDEX EXPANDEDTM 2012 MARCH WEB OF SCIENCE® - TITLE ISSN E-ISSN COUNTRY PUBLISHER 4OR-A Quarterly Journal of Operations Research 1619-4500 1614-2411 GERMANY SPRINGER HEIDELBERG AAPG BULLETIN 0149-1423 UNITED STATES AMER ASSOC PETROLEUM GEOLOGIST AAPS Journal 1550-7416 1550-7416 UNITED STATES SPRINGER AAPS PHARMSCITECH 1530-9932 1530-9932 UNITED STATES SPRINGER AMER ASSOC TEXTILE CHEMISTS AATCC REVIEW 1532-8813 UNITED STATES COLORISTS Abstract and Applied Analysis 1085-3375 1687-0409 UNITED STATES HINDAWI PUBLISHING CORPORATION ABDOMINAL IMAGING 0942-8925 1432-0509 UNITED STATES SPRINGER ABHANDLUNGEN AUS DEM MATHEMATISCHEN SEMINAR DER 0025-5858 1865-8784 GERMANY SPRINGER HEIDELBERG UNIVERSITAT HAMBURG ABSTRACTS OF PAPERS OF THE AMERICAN CHEMICAL 0065-7727 UNITED STATES AMER CHEMICAL SOC SOCIETY Academic Pediatrics 1876-2859 1876-2867 UNITED STATES ELSEVIER SCIENCE INC Accountability in Research-Policies and Quality Assurance 0898-9621 1545-5815 UNITED STATES TAYLOR & FRANCIS LTD Acoustics Australia 0814-6039 AUSTRALIA AUSTRALIAN ACOUSTICAL SOC UNIV CHILE, CENTRO INTERDISCIPLINARIO Acta Bioethica 0717-5906 1726-569X CHILE ESTUDIOS BIOETICA Acta Biomaterialia 1742-7061 1878-7568 ENGLAND ELSEVIER SCI LTD Acta Botanica Brasilica 0102-3306 1677-941X BRAZIL SOC BOTANICA BRASIL Acta Botanica Mexicana 0187-7151 MEXICO INST ECOLOGIA AC Acta Cardiologica Sinica 1011-6842 TAIWAN TAIWAN SOC CARDIOLOGY Acta Chirurgiae Orthopaedicae et Traumatologiae Cechoslovaca -

Population Trends and Migration Strategy of the Wood Sandpiper Tringa Glareola at Ottenby, SE Sweden

Ringing & Migration , 2013 Vol. 28 , No. 1, 6 –15, http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/03078698.2013.811157 Population trends and migration strategy of the Wood Sandpiper Tringa glareola at Ottenby, SE Sweden SOLADOYE BABATOLA IWAJOMO 1,2*, MARTIN STERVANDER 3,4, ANDERS HELSETH 4 and ULF OTTOSSON 2,4 1Natural History Museum of Denmark, Centre for Macroecology, Evolution and Climate, University of Copenhagen, Universitetsparken 15, DK-2100, Copenhagen, Denmark 2A.P. Leventis Ornithological Research Institute (University of Jos Biological Conservatory), PO Box 13404, Jos, Nigeria 3Molecular Ecology and Evolution Lab, Department of Biology, Lund University, Ecology Building, SE-223 62 Lund, Sweden 4Ottenby Bird Observatory, Ottenby 401, SE-386 64 Degerhamn, Sweden Long-term ringing data are useful for understanding population trends and migration strategies adopted by migratory bird species during migration. To investigate the patterns in demography, phenology of migration and stopover behaviour in Wood Sandpipers Tringa glareola trapped on autumn migration at Ottenby, southeast Sweden, in 1947 − 2011, we analysed 65 years of autumn ringing data to describe age- specific trends in annual trappings, morphometrics and phenology, as well as fuel deposition rates and stopover duration from recapture data. We also analysed the migratory direction of the species from recovery data. Over the years, trapping of both adults and juveniles has declined significantly. Median trapping dates were 10 July for adults and 6 August for juveniles. Average migration speed of juvenile birds was 58.1 km d −1. Adults stayed on average 3.5 days and juveniles 5.2 days, with average fuel deposition rates of 2.5 and 0.7 g day −1 respectively. -

Journal Impact Factor 2002

Journal Impact Factor 2002 1.185 AAPG BULLETIN-AMERICAN ASSOCIATION OF PETROLEUM GEOLOGISTS 1.700 AAPS PHARMSCI 0.282 AATCC REVIEW 1.100 ABDOMINAL IMAGING 0.096 ABHANDLUNGEN AUS DEM MATHEMATISCHEN SEMINAR DER UNIVERSITAT HAMBURG 1.535 ACADEMIC EMERGENCY MEDICINE 1.302 ACADEMIC MEDICINE 1.459 ACADEMIC RADIOLOGY 15.901 ACCOUNTS OF CHEMICAL RESEARCH 0.658 ACCREDITATION AND QUALITY ASSURANCE 0.571 ACH-MODELS IN CHEMISTRY 0.632 ACI MATERIALS JOURNAL 0.534 ACI STRUCTURAL JOURNAL 2.769 ACM COMPUTING SURVEYS 0.190 ACM SIGPLAN NOTICES 1.200 ACM TRANSACTIONS ON COMPUTER SYSTEMS 0.875 ACM TRANSACTIONS ON DATABASE SYSTEMS 0.738 ACM TRANSACTIONS ON ON DESIGN AUTOMATION OF ELECTRONIC SYSTEMS 1.048 ACM TRANSACTIONS ON GRAPHICS 1.385 ACM TRANSACTIONS ON INFORMATION SYSTEMS 0.709 ACM TRANSACTIONS ON MATHEMATICAL SOFTWARE 1.000 ACM TRANSACTIONS ON PROGRAMMING LANGUAGES AND SYSTEMS 1.040 ACM TRA NSACTIONS ON SOFTWARE ENGINEERING METHODS 0.447 ACOUSTICAL PHYSICS 0.348 ACSMS HEALTH & FITNESS JOURNAL - ACTA ACUSTICA UNITED WITH ACUSTICA 0.554 ACTA AGRICULTURAE SCANDINAVICA SECTION A-ANIMAL SCIENCE 0.256 ACTA AGRICULTURA E SCANDINAVICA SECTION B-SOIL AND PLANT SCIENCE 0.284 ACTA ALIMENTARIA HUNG 1.508 ACTA ANAESTHESIOLOGICA SCANDINAVICA 0.353 ACTA APPLICANDAE MATHEMATICAE 0.484 ACTA ARITHMETICA 0.284 ACTA ASTRONAUTICA 3.154 ACTA ASTRONOMICA 0.596 ACTA BIOCHIMICA ET BIOPHYSICA SINICA 0.600 ACTA BIOCHIMICA POLONICA 0.269 ACTA BIOLOGICA CRACOVIENSIA SERIES BOTANICA 0.416 ACTA BIOLOGICA HUNGARICA 0.113 ACTA BIOQUIMICA CLINICA LATINOAMERICANA 0.542 ACTA BIOTECHNOLOGICA