Effects of Geographic Location and Habitat on Breeding Parameters of Great Tits

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Are Tits Really Unsuitable Hosts for the Common Cuckoo?

Ornis Fennica 91:0000. 2014 Are tits really unsuitable hosts for the Common Cuckoo? Tomá Grim*, Peter Sama, Petr Procházka & Jarkko Rutila T. Grim & P. Sama, Department of Zoology and Laboratory of Ornithology, Palacký University, 17. listopadu 50, CZ-77146 Olomouc, Czech Republic. * Corresponding au- thors e-mail: [email protected] P. Procházka, Institute of Vertebrate Biology, Academy of Sciences of the Czech Repub- lic, v. v. i., Kvìtná 8, CZ-60365 Brno, Czech Republic J. Rutila, Kannelkatu 5 as 26, 53100 Lappeenranta, Finland Received 19 January 2014, accepted 18 March 2014 Avian brood parasites exploit hosts that have accessible nests and a soft insect diet. Com- mon Cuckoo (Cuculus canorus) hosts were traditionally classified as suitable if both pa- rameters were fulfilled or unsuitable if one, or both, were not. In line with this view, hole- nesting tits (Paridae) have become a text-book example of unsuitable Cuckoo hosts. Our extensive literature search for Cuckoo eggs hatched and chicks raised by hosts revealed 16 Cuckoo nestlings in Great Tit (Parus major) nests, 2 nestlings and 2 fledglings in Blue Tits (Cyanistes caeruleus), and 1 nestling in a Crested Tit (Lophophanes cristatus)nest. Our own data from natural observations and cross-fostering experiments concur with lit- erature data that Great Tits are able to rear Cuckoo chicks to fledging. The natural obser- vations involve the first known cases where a bird species became parasitized as a by- product of nest usurpation (take-over). Surprisingly, Cuckoo chicks raised by Great Tits grew better than Cuckoo chicks raised by common hosts, even alongside host own chicks. -

Proceedings of the United States National Museum

i procp:edings of uxited states national :\[uset7m. 359 23498 g. D. 13 5 A. 14; Y. 3; P. 35; 0. 31 ; B. S. Leiigtli ICT millime- ters. GGGl. 17 specimeus. St. Michaels, Alaslai. II. M. Bannister. a. Length 210 millimeters. D. 13; A. 14; V. 3; P. 33; C— ; B. 8. h. Length 200 millimeters. D. 14: A. 14; Y. 3; P. 35; C— ; B. 8. e. Length 135 millimeters. D. 12: A. 14; Y. 3; P. 35; C. 30; B. 8. The remaining fourteen specimens vary in length from 110 to 180 mil- limeters. United States National Museum, WasJiingtoiij January 5, 1880. FOURTBI III\.STAI.:HEIVT OF ©R!VBTBIOI.O«ICAI. BIBI.IOCiRAPHV r BE:INC} a Jf.ffJ^T ©F FAUIVA!. I»l.TjBf.S«'ATI©.\S REff,ATIIV« T© BRIT- I!§H RIRD!^. My BR. ELS^IOTT COUES, U. S. A. The zlppendix to the "Birds of the Colorado Yalley- (pp. 507 [lJ-784 [218]), which gives the titles of "Faunal Publications" relating to North American Birds, is to be considered as the first instalment of a "Uni- versal Bibliography of Ornithology''. The second instalment occupies pp. 230-330 of the " Bulletin of the United States Geological and Geographical Survey of the Territories 'V Yol. Y, No. 2, Sept. G, 1879, and similarly gives the titles of "Faunal Publications" relating to the Birds of the rest of America.. The.third instalment, which occnpies the same "Bulletin", same Yol.,, No. 4 (in press), consists of an entirely different set of titles, being those belonging to the "systematic" department of the whole Bibliography^ in so far as America is concerned. -

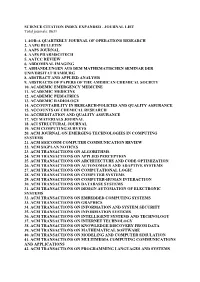

SCIENCE CITATION INDEX EXPANDED - JOURNAL LIST Total Journals: 8631

SCIENCE CITATION INDEX EXPANDED - JOURNAL LIST Total journals: 8631 1. 4OR-A QUARTERLY JOURNAL OF OPERATIONS RESEARCH 2. AAPG BULLETIN 3. AAPS JOURNAL 4. AAPS PHARMSCITECH 5. AATCC REVIEW 6. ABDOMINAL IMAGING 7. ABHANDLUNGEN AUS DEM MATHEMATISCHEN SEMINAR DER UNIVERSITAT HAMBURG 8. ABSTRACT AND APPLIED ANALYSIS 9. ABSTRACTS OF PAPERS OF THE AMERICAN CHEMICAL SOCIETY 10. ACADEMIC EMERGENCY MEDICINE 11. ACADEMIC MEDICINE 12. ACADEMIC PEDIATRICS 13. ACADEMIC RADIOLOGY 14. ACCOUNTABILITY IN RESEARCH-POLICIES AND QUALITY ASSURANCE 15. ACCOUNTS OF CHEMICAL RESEARCH 16. ACCREDITATION AND QUALITY ASSURANCE 17. ACI MATERIALS JOURNAL 18. ACI STRUCTURAL JOURNAL 19. ACM COMPUTING SURVEYS 20. ACM JOURNAL ON EMERGING TECHNOLOGIES IN COMPUTING SYSTEMS 21. ACM SIGCOMM COMPUTER COMMUNICATION REVIEW 22. ACM SIGPLAN NOTICES 23. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON ALGORITHMS 24. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON APPLIED PERCEPTION 25. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON ARCHITECTURE AND CODE OPTIMIZATION 26. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON AUTONOMOUS AND ADAPTIVE SYSTEMS 27. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON COMPUTATIONAL LOGIC 28. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON COMPUTER SYSTEMS 29. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON COMPUTER-HUMAN INTERACTION 30. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON DATABASE SYSTEMS 31. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON DESIGN AUTOMATION OF ELECTRONIC SYSTEMS 32. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON EMBEDDED COMPUTING SYSTEMS 33. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON GRAPHICS 34. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON INFORMATION AND SYSTEM SECURITY 35. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON INFORMATION SYSTEMS 36. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON INTELLIGENT SYSTEMS AND TECHNOLOGY 37. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON INTERNET TECHNOLOGY 38. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON KNOWLEDGE DISCOVERY FROM DATA 39. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON MATHEMATICAL SOFTWARE 40. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON MODELING AND COMPUTER SIMULATION 41. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON MULTIMEDIA COMPUTING COMMUNICATIONS AND APPLICATIONS 42. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON PROGRAMMING LANGUAGES AND SYSTEMS 43. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON RECONFIGURABLE TECHNOLOGY AND SYSTEMS 44. -

Print BB December

Racial identification and assessment in Britain: a report from the RIACT subcommittee Chris Kehoe, on behalf of BBRC Male ‘Black-headed Wagtail’ Motacilla flava feldegg. Dan Powell hroughout the past 100 years or so, mous in this paper), of a single, wide-ranging interest in the racial identification of bird species. The ground-breaking Handbook of Tspecies has blown hot and cold. Many of British Birds (Witherby et al. 1938–41) was the today’s familiar species were first described first popular work that attempted a detailed during the nineteenth century and, as interest treatment of racial variation within the species in new forms grew, many collectors became it covered and promoted a positive approach to increasingly eager to describe and name new the identification of many races. However, as species. Inevitably, many ‘species’ were the emphasis on collecting specimens was described based on minor variations among the replaced by the development of field identifica- specimens collected. As attitudes towards what tion skills, interest in the racial identification of constituted a species changed, many of these species waned. newly described species were subsequently Since the 1970s, and particularly in the last amalgamated as subspecies, or races (the terms ten years, improvements in the quality and ‘subspecies’ and ‘race’ are treated as synony- portability of optics, photographic equipment © British Birds 99 • December 2006 • 619–645 619 Racial identification and assessment in Britain and sound-recording equipment have enabled selection of others suspected of occurring but birders to record much more detail about the not yet confirmed. Any races not listed here are appearance of birds in the field, and this has either deemed too common to be assessed at been an important factor in a major resurgence national level, or would represent a ‘first’ for of interest in racial identification. -

A. Gosler Publications: 2013. Book Chapter. Gosler, A.G., Bhagwat, S., Harrop, S., Bonta, M. & Tidemann, S. (2013) Chapter 6

A. Gosler Publications: 2013. Book chapter. Gosler, A.G., Bhagwat, S., Harrop, S., Bonta, M. & Tidemann, S. (2013) Chapter 6: Leadership and listening: inspiration for conservation mission and advocacy. In Macdonald, D. & Willis, K.J. (eds) Key Topics in Conservation Biology 2. J. Wiley & Sons, Ltd., Oxford. In Press. 2013. Advice Note to SCB Policy Committee. Lee J, Gosler AG, Vyas D, Schaefer J, Chong KY, Kahumbu P, Awoyemi SM & Baugh T. Religion and Conservation Research Collaborative (RCRC) of the Religion and Conservation Biology Working Group (RCBWG) Society for Conservation Biology (SCB)’s Position on the Use of Ivory for Religious Objects. ....................................................................................................... 2012. Letter to Editor. Awoyemi, S.M., Gosler, A.G., Ho, I., Schaefer, J. & Chong, KY. Mobilizing Religion and Conservation in Asia. Science 338: 1537-1538. [doi: 10.1126/science.338.6114.1537-b] 2012. Advice note to SCB Policy Committee. Awoyemi SM, Schaefer J, Gosler A, Baugh T, Chong KY & Landen E. Religion and Conservation Research Collaborative (RCRC) of the Religion and Conservation Biology Working Group (RCBWG) Society for Conservation Biology (SCB)’s Position on the Religious Practice of Releasing Captive Wildlife for Merit. 2012. Scientific Paper. Briggs BD, Hill DA & Gosler AG*. Habitat selection and waterbody-complex use by wintering Gadwall and Shoveler in South West London: implications for the designation and management of multi-site protected areas. Journal for Nature Conservation, 20, 200- 210. [doi: 10.1016/j.jnc.2012.04.002] 2012. Advice note to Libyan National Assembly. Environmental Security in the Libyan Constitution. 2012. Scientific Paper. Bulla M, Šálek M, Gosler AG. Eggshell spotting does not predict male incubation, but marks thinner areas of a shorebird’s shells. -

Status and Diet of the European Shag (Mediterranean Subspecies) Phalacrocorax Aristotelis Desmarestii in the Libyan Sea (South Crete) During the Breeding Season

Xirouchakis et alContributed.: European ShagPapers in the Libyan Sea 1 STATUS AND DIET OF THE EUROPEAN SHAG (MEDITERRANEAN SUBSPECIES) PHALACROCORAX ARISTOTELIS DESMARESTII IN THE LIBYAN SEA (SOUTH CRETE) DURING THE BREEDING SEASON STAVROS M. XIROUCHAKIS1, PANAGIOTIS KASAPIDIS2, ARIS CHRISTIDIS3, GIORGOS ANDREOU1, IOANNIS KONTOGEORGOS4 & PETROS LYMBERAKIS1 1Natural History Museum of Crete, University of Crete, P.O. Box 2208, Heraklion 71409, Crete, Greece ([email protected]) 2Institute of Marine Biology, Biotechnology & Aquaculture, Hellenic Centre for Marine Research (HCMR), P.O. Box 2214, Heraklion 71003, Crete, Greece 3Fisheries Research Institute, Hellenic Agricultural Organization DEMETER, Nea Peramos, Kavala 64007, Macedonia, Greece 4Department of Biology, University of Crete, P.O. Box 2208, Heraklion 71409, Crete, Greece Received 21 June 2016, accepted 21 September 2016 ABSTRACT XIROUCHAKIS, S.M., KASAPIDIS, P., CHRISTIDIS, A., ANDREOU, G., KONTOGEORGOS, I. & LYMBERAKIS, P. 2017. Status and diet of the European Shag (Mediterranean subspecies) Phalacrocorax aristotelis desmarestii in the Libyan Sea (south Crete) during the breeding season. Marine Ornithology 45: 1–9. During 2010–2012 we collected data on the population status and ecology of the European Shag (Mediterranean subspecies) Phalacrocorax aristotelis desmarestii on Gavdos Island (south Crete), conducting boat-based surveys, nest monitoring, and diet analysis. The species’ population was estimated at 80–110 pairs, with 59% breeding success and 1.6 fledglings per successful nest. Pellet morphological and genetic analysis of otoliths and fish bones, respectively, showed that the shags’ diet consisted of 31 species. A total of 4 223 otoliths were identified to species level; 47.2% belonged to sand smelts Atherina boyeri, 14.2% to bogues Boops boops, 11.3% to picarels Spicara smaris, and 10.5% to damselfishes Chromis chromis. -

Articles Recorded During the Urban Predation Search. Columns Show

Table S1: Articles recorded during the urban predation search. Columns show: authors, source of the article (exhaustive review, snowball from the articles of the review and other sources), year of publication, Biome, country and city of the study area, habitat studied (U=urban; core of the city, P=peri-urban; areas surrounding the city and U/P=both, urban and peri-urban), number of inhabitants of the city during the study period and predator species recorded in the study. Reference Source Year Biome Continent Country City Habitat Pop. Size Predator species Ali and Santhanakrishnan Other 2012 Tropical and subtropical Asia India Madurai district U 3 million Tyto alba, Athene brama dry broadleaf forest Allen et al. Other 2016 Tropical and subtropical Oceania Australia Queensland P 5 million Canis lupus dingo, Canis lupus familiaris dry broadleaf forest Apathy Other 1998 Temperate broadleaf Europe Hungary Budapest U 1.8 million Martes foina and mixed forest Baker et al. Review 2005 Temperate broadleaf Europe UK Bristol U 535,907 Felis catus and mixed forest Baker et al. Review 2008 Temperate broadleaf Europe UK Bristol U 535,907 Felis catus and mixed forest Balakrishna Review 2014 Tropical and subtropical Asia India Bangalore P 8.4 million Psammophilus dorsalis dry broadleaf forest Barratt Snowball 1998 Temperate broadleaf Oceania Australia Canberra U 300,000 Felis catus and mixed forest Barratt Snowball 1997 Temperate broadleaf Oceania Australia Canberra U 300,000 Felis catus and mixed forest Beckerman et al. Snowball 2007 Temperate broadleaf Europe UK Unspecified U/P Unspecified Felis catus and mixed forest Bocz et al. -

Acta Ornithologica, 49 (2)

This is a peer-reviewed, post-print (final draft post-refereeing) version of the following published document and is licensed under All Rights Reserved license: Goodenough, Anne E ORCID: 0000-0002-7662-6670 (2014) Effects of Habitat on Breeding Success in a Declining Migrant Songbird: the Case of Pied Flycatcher Ficedula Hypoleuca. Acta Ornithologica, 49 (2). pp. 157-173. doi:10.3161/173484714X687046 Official URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.3161/173484714X687046 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.3161/173484714X687046 EPrint URI: http://eprints.glos.ac.uk/id/eprint/3356 Disclaimer The University of Gloucestershire has obtained warranties from all depositors as to their title in the material deposited and as to their right to deposit such material. The University of Gloucestershire makes no representation or warranties of commercial utility, title, or fitness for a particular purpose or any other warranty, express or implied in respect of any material deposited. The University of Gloucestershire makes no representation that the use of the materials will not infringe any patent, copyright, trademark or other property or proprietary rights. The University of Gloucestershire accepts no liability for any infringement of intellectual property rights in any material deposited but will remove such material from public view pending investigation in the event of an allegation of any such infringement. PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR TEXT. This is a peer-reviewed, post-print (final draft post-refereeing) version of the following published document: Goodenough, Anne E (2014). Effects of Habitat on Breeding Success in a Declining Migrant Songbird: the Case of Pied FlycatcherFicedula hypoleuca. Acta Ornithologica, 49 (2), 157-173. -

2018 Journal Citation Reports Journals in the 2018 Release of JCR 2 Journals in the 2018 Release of JCR

2018 Journal Citation Reports Journals in the 2018 release of JCR 2 Journals in the 2018 release of JCR Abbreviated Title Full Title Country/Region SCIE SSCI 2D MATER 2D MATERIALS England ✓ 3 BIOTECH 3 BIOTECH Germany ✓ 3D PRINT ADDIT MANUF 3D PRINTING AND ADDITIVE MANUFACTURING United States ✓ 4OR-A QUARTERLY JOURNAL OF 4OR-Q J OPER RES OPERATIONS RESEARCH Germany ✓ AAPG BULL AAPG BULLETIN United States ✓ AAPS J AAPS JOURNAL United States ✓ AAPS PHARMSCITECH AAPS PHARMSCITECH United States ✓ AATCC J RES AATCC JOURNAL OF RESEARCH United States ✓ AATCC REV AATCC REVIEW United States ✓ ABACUS-A JOURNAL OF ACCOUNTING ABACUS FINANCE AND BUSINESS STUDIES Australia ✓ ABDOM IMAGING ABDOMINAL IMAGING United States ✓ ABDOM RADIOL ABDOMINAL RADIOLOGY United States ✓ ABHANDLUNGEN AUS DEM MATHEMATISCHEN ABH MATH SEM HAMBURG SEMINAR DER UNIVERSITAT HAMBURG Germany ✓ ACADEMIA-REVISTA LATINOAMERICANA ACAD-REV LATINOAM AD DE ADMINISTRACION Colombia ✓ ACAD EMERG MED ACADEMIC EMERGENCY MEDICINE United States ✓ ACAD MED ACADEMIC MEDICINE United States ✓ ACAD PEDIATR ACADEMIC PEDIATRICS United States ✓ ACAD PSYCHIATR ACADEMIC PSYCHIATRY United States ✓ ACAD RADIOL ACADEMIC RADIOLOGY United States ✓ ACAD MANAG ANN ACADEMY OF MANAGEMENT ANNALS United States ✓ ACAD MANAGE J ACADEMY OF MANAGEMENT JOURNAL United States ✓ ACAD MANAG LEARN EDU ACADEMY OF MANAGEMENT LEARNING & EDUCATION United States ✓ ACAD MANAGE PERSPECT ACADEMY OF MANAGEMENT PERSPECTIVES United States ✓ ACAD MANAGE REV ACADEMY OF MANAGEMENT REVIEW United States ✓ ACAROLOGIA ACAROLOGIA France ✓ -

Journal Impact Factor 2007

Journal Impact Factor 2007 Number Journal Name ISSN Impact 1 AAPG BULLETIN 0149-1423 01.273 2 AAPS Journal 1550-7416 03.756 3 AAPS PHARMSCITECH 1530-9932 01.351 4 AATCC REVIEW 1532-8813 00.478 5 ABDOMINAL IMAGING 0942-8925 01.213 ABHANDLUNGEN AUS DEM MATHEMATISCHEN SEMINAR DER UNIVERSITAT 6 HAMBURG 0025-5858 00.118 7 Abstract and Applied Analysis 1085-3375 00.163 8 ACADEMIC EMERGENCY MEDICINE 1069-6563 01.990 9 ACADEMIC MEDICINE 1040-2446 02.571 10 ACADEMIC RADIOLOGY 1076-6332 02.094 11 ACCOUNTS OF CHEMICAL RESEARCH 0001-4842 16.214 12 ACCREDITATION AND QUALITY ASSURANCE 0949-1775 00.717 13 ACI MATERIALS JOURNAL 0889-325X 00.670 14 ACI STRUCTURAL JOURNAL 0889-3241 00.665 15 ACM COMPUTING SURVEYS 0360-0300 05.250 16 ACM SIGPLAN NOTICES 0362-1340 00.108 17 ACM TRANSACTIONS ON COMPUTER SYSTEMS 0734-2071 01.917 18 ACM TRANSACTIONS ON DATABASE SYSTEMS 0362-5915 02.078 19 ACM TRANSACTIONS ON DESIGN AUTOMATION OF ELECTRONIC SYSTEMS 1084-4309 00.573 20 ACM TRANSACTIONS ON GRAPHICS 0730-0301 03.413 21 ACM TRANSACTIONS ON INFORMATION SYSTEMS 1046-8188 01.969 22 ACM TRANSACTIONS ON MATHEMATICAL SOFTWARE 0098-3500 01.714 23 ACM TRANSACTIONS ON PROGRAMMING LANGUAGES AND SYSTEMS 0164-0925 01.220 24 ACM TRANSACTIONS ON SOFTWARE ENGINEERING AND METHODOLOGY 1049-331X 02.792 25 ACOUSTICAL PHYSICS 1063-7710 00.416 26 ACOUSTICS RESEARCH LETTERS ONLINE-ARLO 1529-7853 01.083 27 ACS Chemical Biology 1554-8929 04.741 28 ACS Nano 1936-0851 29 ACSMS HEALTH & FITNESS JOURNAL 1091-5397 00.082 30 ACTA ACUSTICA UNITED WITH ACUSTICA 1610-1928 00.707 31 ACTA AGRICULTURAE -

A Novel Approach to Detect Long-Term Changes in Terrestrial Faunal Abundance Using Historical Qualitative Descriptions

EUROPEAN JOURNAL OF ECOLOGY EJE 2015, 1(1): 32-42, doi: 10.1515/eje-2015-0005 Pushing back the baseline: a novel approach to detect long-term changes in terrestrial faunal abundance using historical qualitative descriptions 1 2 2,3,4,5 Duncan McCollin , Richard C. Preece , Tim H. Sparks 1Landscape and Biodi- ABSTRACT versity Research Group, Studies that examine changes in the populations of flora and fauna often do so against a baseline of relatively School of Science and recent distribution data. It is much rarer to see evaluations of population change over the longer–term in order Technology, The Univer- sity of Northampton, NN2 to extend the baseline back in time. Here, we use two methods (regression analysis and line of equality) to 6JD, UK, Corresponding identify long-term differences in abundance derived from qualitative descriptions, and we test the efficacy of Author, E-mail: Duncan. this approach by comparison with contemporary data. We take descriptions of bird population abundance in McCollin@northampton. Cambridgeshire, UK, from the first half of the 19th century and compare these with more recent estimates by ac.uk converting qualitative descriptions to an ordinal scale. We show, first, that the ordinal scale of abundance cor- 2Department of Zoology, responds well to quantitative estimates of density and range size based on current data, and, second, that the University of Cambridge, two methods of comparison revealed both increases and declines in species, some of which were consistent Cambridge CB2 3EJ, UK using both approaches but others showed differing responses. We also show that the regional rates of extinction 3Fachgebiet für Ökokli- (extirpation) for birds are twice as high as equivalent rates for plants. -

The Ibis, Journal of the British Ornithologists' Union: a Pre-Synthesis Poredacted for Privacy Abstract Approved: Paul L

AN ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS OF Kristin Renee Johnson for the degree of Master of Science in History of Science, th presented on August 7 , 2000. Title: The Ibis, Journal of the British Ornithologists' Union: A Pre-Synthesis poRedacted for privacy Abstract approved: Paul L. Farber In 1959 the British Ornithological journal, The Ibis, published a centenary commemorative volume on the history of ornithology in Britain. Over the previous few decades, the contributors to this volume had helped focus the attention of ornithologists on the methods, priorities, and problems of modem biology, specifically the theory ofevolution by natural selection and the study ofecology and behaviour. Various new institutions like the Edward Grey Institute ofField Ornithology symbolized the increasing professionalization of both the discipline's institutional networks and publications, which the contents of The Ibis reflected in its increasing number ofcontributions from university educated ornithologists working on specific biological problems. In looking back on the history of their discipline, the contributors to this centenary described both nineteenth century ornithology and the continued dominance oftraditional work in the pages of The Ibis in distinctive ways. They characterized them as oriented around specimens, collections, the seemingly endless gathering of facts, without reference to theoretical problems. The centenary contributors then juxtaposed this portrait in opposition to the contents ofa modem volume, with its use of statistics, graphs, and tables, and the focus ofornithologists on both natural selection and the living bird in its natural environment. This thesis returns to the contents ofthe pre-1940s volumes of The Ibis in order to examine the context and intent ofthose ornithologists characterized as "hide-bound" by the centenary contributors.