Birdwatching Birdwatching

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

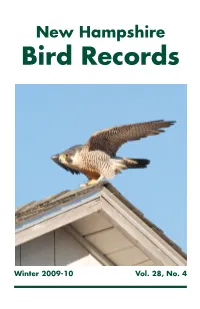

NH Bird Records

V28 No4-Winter09-10_f 8/22/10 4:45 PM Page i New Hampshire Bird Records Winter 2009-10 Vol. 28, No. 4 V28 No4-Winter09-10_f 8/22/10 4:45 PM Page ii AUDUBON SOCIETY OF NEW HAMPSHIRE New Hampshire Bird Records Volume 28, Number 4 Winter 2009-10 Managing Editor: Rebecca Suomala 603-224-9909 X309, [email protected] Text Editor: Dan Hubbard Season Editors: Pamela Hunt, Spring; Tony Vazzano, Summer; Stephen Mirick, Fall; David Deifik, Winter Layout: Kathy McBride Assistants: Jeannine Ayer, Lynn Edwards, Margot Johnson, Susan MacLeod, Marie Nickerson, Carol Plato, William Taffe, Jean Tasker, Tony Vazzano Photo Quiz: David Donsker Photo Editor: Jon Woolf Web Master: Len Medlock Editorial Team: Phil Brown, Hank Chary, David Deifik, David Donsker, Dan Hubbard, Pam Hunt, Iain MacLeod, Len Medlock, Stephen Mirick, Robert Quinn, Rebecca Suomala, William Taffe, Lance Tanino, Tony Vazzano, Jon Woolf Cover Photo: Peregrine Falcon by Jon Woolf, 12/1/09, Hampton Beach State Park, Hampton, NH. New Hampshire Bird Records is published quarterly by New Hampshire Audubon’s Conservation Department. Bird sight- ings are submitted to NH eBird (www.ebird.org/nh) by many different observers. Records are selected for publication and not all species reported will appear in the issue. The published sightings typically represent the highlights of the season. All records are subject to review by the NH Rare Birds Committee and publication of reports here does not imply future acceptance by the Committee. Please contact the Managing Editor if you would like to report your sightings but are unable to use NH eBird. -

January 2020.Indd

BROWN PELICAN Photo by Rob Swindell at Melbourne, Florida JANUARY 2020 Editors: Jim Jablonski, Marty Ackermann, Tammy Martin, Cathy Priebe Webmistress: Arlene Lengyel January 2020 Program Tuesday, January 7, 2020, 7 p.m. Carlisle Reservation Visitor Center Gulls 101 Chuck Slusarczyk, Jr. "I'm happy to be presenting my program Gulls 101 to the good people of Black River Audubon. Gulls are notoriously difficult to identify, but I hope to at least get you looking at them a little closer. Even though I know a bit about them, I'm far from an expert in the field and there is always more to learn. The challenge is to know the particular field marks that are most important, and familiarization with the many plumage cycles helps a lot too. No one will come out of this presentation an expert, but I hope that I can at least give you an idea what to look for. At the very least, I hope you enjoy the photos. Looking forward to seeing everyone there!” Chuck Slusarczyk is an avid member of the Ohio birding community, and his efforts to assist and educate novice birders via social media are well known, yet he is the first to admit that one never stops learning. He has presented a number of programs to Black River Audubon, always drawing a large, appreciative gathering. 2019 Wellington Area Christmas Bird Count The Wellington-area CBC will take place Saturday, December 28, 2019. Meet at the McDonald’s on Rt. 58 at 8:00 a.m. The leader is Paul Sherwood. -

BAADER PLANETARIUM PRODUCTS (All Prices in EUR) Products, Pricing and Specifications May Change Without Notice Or Obligation

Pricelist ANDROMEDA Ltd. October 2020 BAADER PLANETARIUM PRODUCTS (All prices in EUR) Products, pricing and specifications may change without notice or obligation. Section Products 1 Guide Scope Rings + Related Accessories 2 - 4a Dove Tail Systems 3" / V / Z 2 3" (Losmandy style) System, Bars and Clamps 3 V- (Vixen/Celestron/SkyWatcher/EQ) Dove Tail System, Dove Tail Bars and Clamps 4 Z- (Zeiss/Astro Physics) Dove Tail System, Dove Tail Bars and Clamps 4a Custom lengths of Dovetail bars (w/o anodizing) – style 3" or „V“ or „Z“ 5 - 5b Tripods and Adapters: 5 Baader Tripods & Flange Adapters for a variety of mounts 5a Photo Tripod „Astro & Nature“ and Accessories 5b Short Pillar and Universal Pillar Adapter 6 Travel Mount 6a Cases for Telescopes 7 Counterweights: Baader CDP, 10 Micron, custom bore holes 8 Adapters and ClickLock clamps 8 Baader Astro T-2 System – all adapters for T-2 Photo Thread 8a M48 Adapter System 9 2" (SC-thread) Mechanical Adapters, 2" Eyepiece Holders, 2" Extensions 9a 2” ClickLock® (CL) – clamps for SC / AP / M68 / Vixen / SkyWatcher, 2" / 1¼" 10 M68 (Zeiss) Adapter System, Zeiss Extension tubes, M68 Changer & Change Ring 11 Baader Adapters for Pentax / Takahashi / AstroPhysics / TEC & 3" Hyperion 12 - 13 Finderscopes and Accessories 12 Finderscopes, SkySurfer III, Skysurfer V, Vario-Finder 10x60 13 Quick Release Finder Brackets & Accessories, Tangent assemblies, Baader Stronghold 14 - 18 Projection and Photography 14 Digital Adapter System DT-I/DT-II & M68 (Adapters for fixed lens (afocal) photography) 15 ADPS Digital -

Web-Book Catalog 2021-05-10

Lehigh Gap Nature Center Library Book Catalog Title Year Author(s) Publisher Keywords Keywords Catalog No. National Geographic, Washington, 100 best pictures. 2001 National Geogrpahic. Photographs. 779 DC Miller, Jeffrey C., and Daniel H. 100 butterflies and moths : portraits from Belknap Press of Harvard University Butterflies - Costa 2007 Janzen, and Winifred Moths - Costa Rica 595.789097286 th tropical forests of Costa Rica Press, Cambridge, MA rica Hallwachs. Miller, Jeffery C., and Daniel H. 100 caterpillars : portraits from the Belknap Press of Harvard University Caterpillars - Costa 2006 Janzen, and Winifred 595.781 tropical forests of Costa Rica Press, Cambridge, MA Rica Hallwachs 100 plants to feed the bees : provide a 2016 Lee-Mader, Eric, et al. Storey Publishing, North Adams, MA Bees. Pollination 635.9676 healthy habitat to help pollinators thrive Klots, Alexander B., and Elsie 1001 answers to questions about insects 1961 Grosset & Dunlap, New York, NY Insects 595.7 B. Klots Cruickshank, Allan D., and Dodd, Mead, and Company, New 1001 questions answered about birds 1958 Birds 598 Helen Cruickshank York, NY Currie, Philip J. and Eva B. 101 Questions About Dinosaurs 1996 Dover Publications, Inc., Mineola, NY Reptiles Dinosaurs 567.91 Koppelhus Dover Publications, Inc., Mineola, N. 101 Questions About the Seashore 1997 Barlowe, Sy Seashore 577.51 Y. Gardening to attract 101 ways to help birds 2006 Erickson, Laura. Stackpole Books, Mechanicsburg, PA Birds - Conservation. 639.978 birds. Sharpe, Grant, and Wenonah University of Wisconsin Press, 101 wildflowers of Arcadia National Park 1963 581.769909741 Sharpe Madison, WI 1300 real and fanciful animals : from Animals, Mythical in 1998 Merian, Matthaus Dover Publications, Mineola, NY Animals in art 769.432 seventeenth-century engravings. -

Proceedings of the United States National Museum

i procp:edings of uxited states national :\[uset7m. 359 23498 g. D. 13 5 A. 14; Y. 3; P. 35; 0. 31 ; B. S. Leiigtli ICT millime- ters. GGGl. 17 specimeus. St. Michaels, Alaslai. II. M. Bannister. a. Length 210 millimeters. D. 13; A. 14; V. 3; P. 33; C— ; B. 8. h. Length 200 millimeters. D. 14: A. 14; Y. 3; P. 35; C— ; B. 8. e. Length 135 millimeters. D. 12: A. 14; Y. 3; P. 35; C. 30; B. 8. The remaining fourteen specimens vary in length from 110 to 180 mil- limeters. United States National Museum, WasJiingtoiij January 5, 1880. FOURTBI III\.STAI.:HEIVT OF ©R!VBTBIOI.O«ICAI. BIBI.IOCiRAPHV r BE:INC} a Jf.ffJ^T ©F FAUIVA!. I»l.TjBf.S«'ATI©.\S REff,ATIIV« T© BRIT- I!§H RIRD!^. My BR. ELS^IOTT COUES, U. S. A. The zlppendix to the "Birds of the Colorado Yalley- (pp. 507 [lJ-784 [218]), which gives the titles of "Faunal Publications" relating to North American Birds, is to be considered as the first instalment of a "Uni- versal Bibliography of Ornithology''. The second instalment occupies pp. 230-330 of the " Bulletin of the United States Geological and Geographical Survey of the Territories 'V Yol. Y, No. 2, Sept. G, 1879, and similarly gives the titles of "Faunal Publications" relating to the Birds of the rest of America.. The.third instalment, which occnpies the same "Bulletin", same Yol.,, No. 4 (in press), consists of an entirely different set of titles, being those belonging to the "systematic" department of the whole Bibliography^ in so far as America is concerned. -

Elementary School Program

MAST ACADEMY OUTREACH ELEMENTARY SCHOOL PROGRAM Birds of the Everglades Pre-site Package MAST Academy Maritime and Science Technology High School Miami-Dade County Public Schools Miami, Florida 0 Birds of the Everglades Grade 5 Pre-Site Packet Table of Contents Sunshine State Standards FCAT Benchmarks – Grade 5 i Teacher Instructions 1 Destination: Everglades National Park 3 The Birds of Everglades National Park 4 Everglades Birds: Yesterday and Today 6 Birdwatching Equipment Binoculars 7 A Field Guide 7 Field Notes 8 In-Class Activity 13 Online Resources 19 Answer Key 20 Application for Education Fee Waiver 27 1 BIRDS OF THE EVERGLADES SUNSHINE STATE STANDARDS FCAT BENCHMARKS – Grade 5 Science Benchmarks Assessed at Grade 5 Strand F: Processes of Life SC.F.1.2.3 The student knows that living things are different but share similar structures. Strand G: How Living Things Interact with Their Environment SC.G.1.2.2 The student knows that living things compete in a climatic region with other living things and that structural adaptations make them fit for an environment. SC.G1.2.5 The student knows that animals eat plants or other animals to acquire the energy they need for survival. SC.G1.2.7 The student knows that variations in light, water, temperature, and soil content are largely responsible for the existence of different kinds of organisms and population densities in an ecosystem. SC.G.2.2.2 The student knows that the size of a population is dependent upon the available resources within its community. SC.G.2.2.3 The student understands that changes in the habitat of an organism may be beneficial or harmful. -

BIRDING— Fun and Science by Phyllis Mcintosh

COM . TOCK S HUTTER © S © BIRDING— Fun and Science by Phyllis McIntosh For passionate birdwatcher Sandy Komito of over age 16 say they actively observe and try to iden- Fair Lawn, New Jersey, 1998 was a big year. In a tify birds, although few go to the extremes Komito tight competition with two fellow birders to see as did. About 88 percent are content to enjoy bird many species as possible in a single year, Komito watching in their own backyards or neighborhoods. traveled 270,000 miles, crisscrossing North Amer- More avid participants plan vacations around ica and voyaging far out to sea to locate rare and their hobby and sometimes travel long distances to elusive birds. In the end, he set a North American view a rare species and add it to their lifelong list of record of 748 species, topping his own previous birds spotted. Many birdwatchers, both casual and record of 726, which had stood for 11 years. serious, also function as citizen scientists, provid- Komito and his fellow competitors are not alone ing valuable data to help scientists monitor bird in their love of birds. According to a U.S. Fish and populations and create management guidelines to Wildlife Service survey, about one in five Americans protect species in decline. 36 2 0 1 4 N UMBER 1 | E NGLISH T E ACHING F ORUM Birding Basics The origins of bird watching in the United States date back to the late 1800s when conserva- tionists became concerned about the hunting of birds to supply feathers for the fashion industry. -

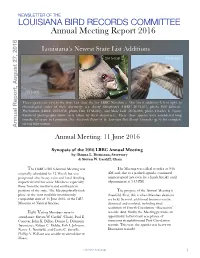

2016 LBRC Newsletter

NEWSLETTER OF THE LOUISIANA BIRD RECORDS COMMITTEE Annual Meeting Report 2016 Louisiana’s Newest State List Additions 2015-058 2016-003 August 27, 2016 2014-031 Three species are new to the State List since the last LBRC Newsletter. Our latest additions (left to right, in chronological order of their discovery) are: Sooty Shearwater (LBRC 2014-031, photo Will Selman), Pyrrhuloxia (LBRC 2015-058, photo Dan O’Malley), and Mew Gull (2016-003, photo Charles E. Lyon). Excellent photographs above were taken by their discoverers. These three species were considered long overdue to occur in Louisiana. See Nineteenth Report of the Louisiana Bird Records Committee (p. 6) for complete record information. Annual Report, Annual Meeting: 11 June 2016 Synopsis of the 2016 LBRC Annual Meeting by: Donna L. Dittmann, Secretary & Steven W. Cardiff, Chair The LBRC’s 2016 Annual Meeting was The Meeting was called to order at 9:56 originally scheduled for 12 March but was AM and, due to a packed agenda, continued postponed after heavy rains and local flooding uninterrupted (not even for a lunch break!) until impacted travel for some Members, especially adjournment at 5:45 PM. those from the northern and southeastern portions of the state. The Meeting finally took The purpose of the Annual Meeting is place on the next available unanimously threefold. First, this is when Member elections compatible date of 11 June 2016, at the LSU are held. Second, additional business can be Museum of Natural Science. discussed and resolved, including final resolution of Fourth Circulation “Discussion” Eight Voting Members were in records. -

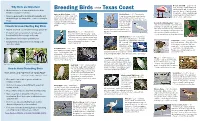

Breeding Birds of the Texas Coast

Roseate Spoonbill • L 32”• Uncom- Why Birds are Important of the mon, declining • Unmistakable pale Breeding Birds Texas Coast pink wading bird with a long bill end- • Bird abundance is an important indicator of the ing in flat “spoon”• Nests on islands health of coastal ecosystems in vegetation • Wades slowly through American White Pelican • L 62” Reddish Egret • L 30”• Threatened in water, sweeping touch-sensitive bill •Common, increasing • Large, white • Revenue generated by hunting, photography, and Texas, decreasing • Dark morph has slate- side to side in search of prey birdwatching helps support the coastal economy in bird with black flight feathers and gray body with reddish breast, neck, and Chuck Tague bright yellow bill and pouch • Nests Texas head; white morph completely white – both in groups on islands with sparse have pink bill with Black-bellied Whistling-Duck vegetation • Preys on small fish in black tip; shaggy- • L 21”• Lo- groups looking plumage cally common, increasing • Goose-like duck Threats to Island-Nesting Bay Birds Chuck Tague with long neck and pink legs, pinkish-red bill, Greg Lavaty • Nests in mixed- species colonies in low vegetation or on black belly, and white eye-ring • Nests in tree • Habitat loss from erosion and wetland degradation cavities • Occasionally nests in mesquite and Brown Pelican • L 51”• Endangered in ground • Uses quick, erratic movements to • Predators such as raccoons, feral hogs, and stir up prey Chuck Tague other woody vegetation on bay islands Texas, but common and increasing • Large -

Birdwatching in Portugal

birdwatchingIN PORTUGAL In this guide, you will find 36 places of interest 03 - for birdwatchers and seven suggestions of itineraries you may wish to follow. 02 Accept the challenge and venture forth around Portugal in search of our birdlife. birdwatching IN PORTUGAL Published by Turismo de Portugal, with technical support from Sociedade Portuguesa para o Estudo das Aves (SPEA) PHOTOGRAPHY Ana Isabel Fagundes © Andy Hay, rspb-images.com Carlos Cabral Faisca Helder Costa Joaquim Teodósio Pedro Monteiro PLGeraldes SPEA/DLeitão Vitor Maia Gerbrand AM Michielsen TEXT Domingos Leitão Alexandra Lopes Ana Isabel Fagundes Cátia Gouveia Carlos Pereira GRP A HIC DESIGN Terradesign Jangada | PLGeraldes 05 - birdwatching 04 Orphean Warbler, Spanish Sparrow). The coastal strip is the preferred place of migration for thousands of birds from dozens of different species. Hundreds of thousands of sea and coastal birds (gannets, shear- waters, sandpipers, plovers and terns), birds of prey (eagles and harriers), small birds (swallows, pipits, warblers, thrushes and shrikes) cross over our territory twice a year, flying between their breeding grounds in Europe and their winter stays in Africa. ortugal is situated in the Mediterranean region, which is one of the world’s most im- In the archipelagos of the Azores and Madeira, there p portant areas in terms of biodiversity. Its are important colonies of seabirds, such as the Cory’s landscape is very varied, with mountains and plains, Shearwater, Bulwer’s Petrel and Roseate Tern. There are hidden valleys and meadowland, extensive forests also some endemic species on the islands, such as the and groves, rocky coasts and never-ending beaches Madeiran Storm Petrel, Madeiran Laurel Pigeon, Ma- that stretch into the distance, estuaries, river deltas deiran Firecrest or the Azores Bullfinch. -

Using a Canon EOS M50 As a Dedicated, Afocal, Microscope Camera Steve Neeley (USA)

Using a Canon EOS M50 as a Dedicated, Afocal, Microscope Camera Steve Neeley (USA) From Wikipedia: “Afocal photography, also called afocal imaging or afocal projection, is a method of photography where the camera with its lens attached is mounted over the eyepiece of another image forming system such as an optical telescope or optical microscope, with the camera lens taking the place of the human eye.” Except for a very few hours experimenting with a borrowed Canon 40D back in 2011, I had no experience with coupling and using a camera with my Leitz Ortholux I microscope. But I was able to get surprisingly good coverage of its sensor – which was encouraging. Above: Phase Contrast Image of a diatom strew slide from experiments with a Canon 40D in 2011. Recently, in trying to rekindle and expand my hobby, I bought my own camera -- a Canon M50 -- to use as a dedicated microscope camera. This article shares my experience in coupling and using the M50 on the Ortholux. Disclaimer. As a colleague often says, “I’m not buying or selling here” – meaning, in this case, that I did earnest, but certainly spotty, research before buying the M50, and it was only after I had it in hand and could work with it on the scope, that I finally understood some things, as in ‘Oh! NOW I understand.” I bought what I could afford, not what was the absolute best solution for my priorities. Not ‘selling’ you on the M50 – you might find something better. 1 Priorities 1. To share my hobby in ‘live view’, on screen, with family so they do not need to use the eyepieces (this is especially hard for children). -

Print BB December

Racial identification and assessment in Britain: a report from the RIACT subcommittee Chris Kehoe, on behalf of BBRC Male ‘Black-headed Wagtail’ Motacilla flava feldegg. Dan Powell hroughout the past 100 years or so, mous in this paper), of a single, wide-ranging interest in the racial identification of bird species. The ground-breaking Handbook of Tspecies has blown hot and cold. Many of British Birds (Witherby et al. 1938–41) was the today’s familiar species were first described first popular work that attempted a detailed during the nineteenth century and, as interest treatment of racial variation within the species in new forms grew, many collectors became it covered and promoted a positive approach to increasingly eager to describe and name new the identification of many races. However, as species. Inevitably, many ‘species’ were the emphasis on collecting specimens was described based on minor variations among the replaced by the development of field identifica- specimens collected. As attitudes towards what tion skills, interest in the racial identification of constituted a species changed, many of these species waned. newly described species were subsequently Since the 1970s, and particularly in the last amalgamated as subspecies, or races (the terms ten years, improvements in the quality and ‘subspecies’ and ‘race’ are treated as synony- portability of optics, photographic equipment © British Birds 99 • December 2006 • 619–645 619 Racial identification and assessment in Britain and sound-recording equipment have enabled selection of others suspected of occurring but birders to record much more detail about the not yet confirmed. Any races not listed here are appearance of birds in the field, and this has either deemed too common to be assessed at been an important factor in a major resurgence national level, or would represent a ‘first’ for of interest in racial identification.