Human Rights

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Grade 6 Reading Student At–Home Activity Packet

Printer Warning: This packet is lengthy. Determine whether you want to print both sections, or only print Section 1 or 2. Grade 6 Reading Student At–Home Activity Packet This At–Home Activity packet includes two parts, Section 1 and Section 2, each with approximately 10 lessons in it. We recommend that your student complete one lesson each day. Most lessons can be completed independently. However, there are some lessons that would benefit from the support of an adult. If there is not an adult available to help, don’t worry! Just skip those lessons. Encourage your student to just do the best they can with this content—the most important thing is that they continue to work on their reading! Flip to see the Grade 6 Reading activities included in this packet! © 2020 Curriculum Associates, LLC. All rights reserved. Section 1 Table of Contents Grade 6 Reading Activities in Section 1 Lesson Resource Instructions Answer Key Page 1 Grade 6 Ready • Read the Guided Practice: Answers will vary. 10–11 Language Handbook, Introduction. Sample answers: Lesson 9 • Complete the 1. Wouldn’t it be fun to learn about Varying Sentence Guided Practice. insect colonies? Patterns • Complete the 2. When I looked at the museum map, Independent I noticed a new insect exhibit. Lesson 9 Varying Sentence Patterns Introduction Good writers use a variety of sentence types. They mix short and long sentences, and they find different ways to start sentences. Here are ways to improve your writing: Practice. Use different sentence types: statements, questions, imperatives, and exclamations. Use different sentence structures: simple, compound, complex, and compound-complex. -

BROKEN PROMISES: Continuing Federal Funding Shortfall for Native Americans

U.S. COMMISSION ON CIVIL RIGHTS BROKEN PROMISES: Continuing Federal Funding Shortfall for Native Americans BRIEFING REPORT U.S. COMMISSION ON CIVIL RIGHTS Washington, DC 20425 Official Business DECEMBER 2018 Penalty for Private Use $300 Visit us on the Web: www.usccr.gov U.S. COMMISSION ON CIVIL RIGHTS MEMBERS OF THE COMMISSION The U.S. Commission on Civil Rights is an independent, Catherine E. Lhamon, Chairperson bipartisan agency established by Congress in 1957. It is Patricia Timmons-Goodson, Vice Chairperson directed to: Debo P. Adegbile Gail L. Heriot • Investigate complaints alleging that citizens are Peter N. Kirsanow being deprived of their right to vote by reason of their David Kladney race, color, religion, sex, age, disability, or national Karen Narasaki origin, or by reason of fraudulent practices. Michael Yaki • Study and collect information relating to discrimination or a denial of equal protection of the laws under the Constitution Mauro Morales, Staff Director because of race, color, religion, sex, age, disability, or national origin, or in the administration of justice. • Appraise federal laws and policies with respect to U.S. Commission on Civil Rights discrimination or denial of equal protection of the laws 1331 Pennsylvania Avenue, NW because of race, color, religion, sex, age, disability, or Washington, DC 20425 national origin, or in the administration of justice. (202) 376-8128 voice • Serve as a national clearinghouse for information TTY Relay: 711 in respect to discrimination or denial of equal protection of the laws because of race, color, www.usccr.gov religion, sex, age, disability, or national origin. • Submit reports, findings, and recommendations to the President and Congress. -

Tracing Fairy Tales in Popular Culture Through the Depiction of Maternity in Three “Snow White” Variants

University of Louisville ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository College of Arts & Sciences Senior Honors Theses College of Arts & Sciences 5-2014 Reflective tales : tracing fairy tales in popular culture through the depiction of maternity in three “Snow White” variants. Alexandra O'Keefe University of Louisville Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.louisville.edu/honors Part of the Children's and Young Adult Literature Commons, and the Comparative Literature Commons Recommended Citation O'Keefe, Alexandra, "Reflective tales : tracing fairy tales in popular culture through the depiction of maternity in three “Snow White” variants." (2014). College of Arts & Sciences Senior Honors Theses. Paper 62. http://doi.org/10.18297/honors/62 This Senior Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Arts & Sciences at ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in College of Arts & Sciences Senior Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. This title appears here courtesy of the author, who has retained all other copyrights. For more information, please contact [email protected]. O’Keefe 1 Reflective Tales: Tracing Fairy Tales in Popular Culture through the Depiction of Maternity in Three “Snow White” Variants By Alexandra O’Keefe Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for Graduation summa cum laude University of Louisville March, 2014 O’Keefe 2 The ability to adapt to the culture they occupy as well as the two-dimensionality of literary fairy tales allows them to relate to readers on a more meaningful level. -

Jekyll and Hyde Plot, Themes, Context and Key Vocabulary Booklet

Jekyll and Hyde Plot, Themes, Context and key vocabulary booklet Name: 1 2 Plot Mr Utterson and his cousin Mr Enfield are out for a walk when they pass a strange-looking door Chapter 1 - (which we later learn is the entrance to Dr Jekyll's laboratory). Enfield recalls a story involving the Story of the door. In the early hours of one winter morning, he says, he saw a man trampling on a young girl. He Door chased the man and brought him back to the scene of the crime. (The reader later learns that the man is Mr Hyde.) A crowd gathered and, to avoid a scene, the man offered to pay the girl compensation. This was accepted, and he opened the door with a key and re-emerged with a large cheque. Utterson is very interested in the case and asks whether Enfield is certain Hyde used a key to open the door. Enfield is sure he did. That evening the lawyer, Utterson, is troubled by what he has heard. He takes the will of his friend Dr Chapter 2 - Jekyll from his safe. It contains a worrying instruction: in the event of Dr Jekyll's disappearance, all his Search for possessions are to go to a Mr Hyde. Mr Hyde Utterson decides to visit Dr Lanyon, an old friend of his and Dr Jekyll's. Lanyon has never heard of Hyde, and not seen Jekyll for ten years. That night Utterson has terrible nightmares. He starts watching the door (which belongs to Dr Jekyll's old laboratory) at all hours, and eventually sees Hyde unlocking it. -

Anti-Terrorism Pre-Crime Measures and International Human Rights Law

GW Law Faculty Publications & Other Works Faculty Scholarship 2020 The Price of Prevention: Anti-Terrorism Pre-Crime Measures and International Human Rights Law, Arturo J. Carrillo George Washington University Law School, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.gwu.edu/faculty_publications Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Arturo J. Carrillo, The Price of Prevention: Anti-Terrorism Pre-Crime Measures and International Human Rights Law, 60 Va. J. Int’l L. 571 (2020) This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in GW Law Faculty Publications & Other Works by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ARTICLE The Price of Prevention: Anti-Terrorism Pre-Crime Measures and International Human Rights Law ARTURO J. CARRILLO* How far can law go to prevent violent acts of terrorism from happening? This Article examines the response by a number of Western democratic States to that question. These States have enacted special legal mechanisms that can be called ‘anti-terrorist pre-crime measures.’ Anti-terrorist pre-crime measures, or ATPCMs for short, are conditions or restrictions imposed on a person by law enforcement authorities as the outcome of a legal process set up to identify and neutralize potential sources of terrorist activity before it occurs. The issue is whether the ATCPMs regimes in existence today comply with the corresponding States’ international obligations under human rights law because, by virtue of their preventative mission, these regimes operate outside, or on the fringes of, the ordinary criminal justice systems in the democratic societies that deploy them. -

The Decline of Dualism: the Relationship Between International Human Rights Treaties and the United Kingdom's Domestic Counter-Terror Laws

The Decline of Dualism: The Relationship Between International Human Rights Treaties and the United Kingdom's Domestic Counter-terror Laws by Craig William Alec Webber Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Laws at the University of South Africa Promoter: Professor Neville Botha November 2012 DECLARATION I declare that ‘The Decline of Dualism: The Relationship Between International Human Rights Treaties and the United Kingdom's Domestic Counter-terror Laws’ is my own work and that all the sources that I have used or quoted have been indicated and acknowledged by means of complete references. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank my promoter, Professor Neville Botha for his exceptionally instructive and meticulous supervision. I have learned a great deal under his careful direction. I would also like to thank my parents and family and especially my Mother for her support, both practical and financial. I also wish to acknowledge Paul Tosio, who was regularly called upon to apply his considerable intellect to matters which fall well outside his many areas of interest. I dedicate this thesis in memory of my grandfather William Currin, who so enjoyed attending his grandchildren’s graduation ceremonies. Craig Webber Cape Town: November 2012 iii SUMMARY In the first half of the 20th Century, the United Kingdom’s counter-terror laws were couched extremely broadly. Consequently, they bestowed upon the executive extraordinarily wide powers with which it could address perceived threats of terrorism. In that period of time, the internal affairs of any state were considered sacrosanct and beyond the reach of international law. -

Anti-Terrorism Control Orders in Australia and the United Kingdom: a Comparison

Parliament of Australia Department of Parliamentary Services Parliamentary Library Information, analysis and advice for the Parliament RESEARCH PAPER www.aph.gov.au/library 29 April 2008, no. 28, 2007–08, ISSN 1834-9854 Anti-terrorism control orders in Australia and the United Kingdom: a comparison Bronwen Jaggers Law and Bills Digests Section Executive summary • Control orders have been part of Australian anti-terrorism legislation since December 2005. A control order is issued by a court (at the request of the Australian Federal Police) to allow obligations, prohibitions and restrictions to be imposed on a person, for the purpose of protecting the public from a terrorist act. The types of obligations, prohibitions and restrictions may include a curfew at a particular address, wearing of an electronic monitoring tag, restrictions on use of telecommunications, regular reporting to police, and a range of other measures. Two control orders have been issued in Australia to date, those applying to Jack Thomas and David Hicks. • Australia’s control order scheme is in part based upon the United Kingdom model, however there are significant differences. • Criticisms of the Australian control order regime include concerns about the ex-parte nature of court hearings for interim control orders, reporting and accountability mechanisms, and questions surrounding whether the restrictions which may be imposed by control orders are sufficiently balanced with human rights protections. Contents Executive summary ..................................................... 1 Introduction ........................................................ 1 The Australian legislation .............................................. 1 Obtaining a control order ............................................. 2 Urgent interim control orders .......................................... 3 Ex-parte court proceedings and provision of documents ...................... 4 Terms of a control order ............................................. 5 Reviews/sunset clause .............................................. -

Download Thepdf

Volume 59, Issue 5 Page 1395 Stanford Law Review KEEPING CONTROL OF TERRORISTS WITHOUT LOSING CONTROL OF CONSTITUTIONALISM Clive Walker © 2007 by the Board of Trustees of the Leland Stanford Junior University, from the Stanford Law Review at 59 STAN. L. REV. 1395 (2007). For information visit http://lawreview.stanford.edu. KEEPING CONTROL OF TERRORISTS WITHOUT LOSING CONTROL OF CONSTITUTIONALISM Clive Walker* INTRODUCTION: THE DYNAMICS OF COUNTER-TERRORISM POLICIES AND LAWS................................................................................................ 1395 I. CONTROL ORDERS ..................................................................................... 1403 A. Background to the Enactment of Control Orders............................... 1403 B. The Replacement System..................................................................... 1408 1. Control orders—outline................................................................ 1408 2. Control orders—contents and issuance........................................ 1411 3. Non-derogating control orders..................................................... 1416 4. Derogating control orders............................................................ 1424 5. Criminal prosecution.................................................................... 1429 6. Ancillary issues............................................................................. 1433 7. Review by Parliament and the Executive...................................... 1443 C. Judicial Review.................................................................................. -

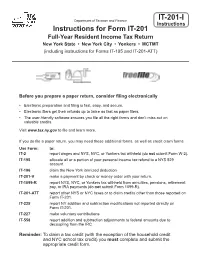

Instructions for Form IT-201 Full-Year Resident Income Tax Return

Department of Taxation and Finance IT-201-I Instructions Instructions for Form IT-201 Full-Year Resident Income Tax Return New York State • New York City • Yonkers • MCTMT (including instructions for Forms IT-195 and IT-201-ATT) Before you prepare a paper return, consider filing electronically • Electronic preparation and filing is fast, easy, and secure. • Electronic filers get their refunds up to twice as fast as paper filers. • The user-friendly software ensures you file all the right forms and don’t miss out on valuable credits. Visit www.tax.ny.gov to file and learn more. If you do file a paper return, you may need these additional forms, as well as credit claim forms. Use Form: to: IT-2 report wages and NYS, NYC, or Yonkers tax withheld (do not submit Form W-2). IT-195 allocate all or a portion of your personal income tax refund to a NYS 529 account. IT-196 claim the New York itemized deduction IT-201-V make a payment by check or money order with your return. IT-1099-R report NYS, NYC, or Yonkers tax withheld from annuities, pensions, retirement pay, or IRA payments (do not submit Form 1099-R). IT-201-ATT report other NYS or NYC taxes or to claim credits other than those reported on Form IT-201. IT-225 report NY addition and subtraction modifications not reported directly on Form IT-201. IT-227 make voluntary contributions IT-558 report addition and subtraction adjustments to federal amounts due to decoupling from the IRC. Reminder: To claim a tax credit (with the exception of the household credit and NYC school tax credit) you must complete and submit the appropriate credit form. -

Kingdom Principles

KINGDOM PRINCIPLES PREPARING FOR KINGDOM EXPERIENCE AND EXPANSION KINGDOM PRINCIPLES PREPARING FOR KINGDOM EXPERIENCE AND EXPANSION Dr. Myles Munroe © Copyright 2006 — Myles Munroe All rights reserved. This book is protected by the copyright laws of the United States of America. This book may not be copied or reprinted for commercial gain or profit. The use of short quotations or occasional page copying for personal or group study is permitted and encouraged. Permission will be granted upon request. Unless other- wise identified, Scripture quotations are from the HOLY BIBLE, NEW INTERNA- TIONAL VERSION Copyright © 1973, 1978, 1984 by International Bible Society. Used by permission of Zondervan Publishing House. All rights reserved. Scripture quotations marked (NKJV) are taken form the New King James Version. Copyright © 1982 by Thomas Nelson, Inc. Used by permission. All rights reserved. Please note that Destiny Image’s publishing style capitalizes certain pronouns in Scripture that refer to the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit, and may differ from some publishers’ styles. Take note that the name satan and related names are not capitalized. We choose not to acknowledge him, even to the point of violating grammatical rules. Cover photography by Andy Adderley, Creative Photography, Nassau, Bahamas Destiny Image® Publishers, Inc. P.O. Box 310 Shippensburg, PA 17257-0310 “Speaking to the Purposes of God for this Generation and for the Generations to Come.” Bahamas Faith Ministry P.O. Box N9583 Nassau, Bahamas For Worldwide Distribution, Printed in the U.S.A. ISBN 10: 0-7684-2373-2 Hardcover ISBN 13: 978-0-7684-2373-0 ISBN 10: 0-7684-2398-8 Paperback ISBN 13: 978-0-7684-2398-3 This book and all other Destiny Image, Revival Press, MercyPlace, Fresh Bread, Destiny Image Fiction, and Treasure House books are available at Christian bookstores and distributors worldwide. -

Clive Walker*

HUMAN RIGHTS AND COUNTERTERRORISM IN THE UK Clive Walker* Introduction Within the dominion of counter-terrorism, policy choices can be stark. One must determine in institutional terms whether the response is to be predominantly military or policing and, cutting across that boundary, which agencies are to predominate and where to direct financial support. There are also choices to be made in corresponding legal regimes around counter-terrorism, ranging from the rules of war and legal states of emergency through to nuanced versions of criminal justice. These counter-terrorism policy choices can determine not only the nature of a society whilst it deals with terrorism but also, as illustrated by the variant experiences of countries such as South Africa or Sri Lanka, compared to Germany and Italy, the nature of that society and its residual scars if and when it emerges from terrorism. It is the thesis here that human rights discourse has grown in importance as a determinant of counter-terrorist strategic choices and modes of tactical delivery. That meaning and impact will be assessed alongside other normative considerations such as democratic accountability. This promise of human rights impact appears somewhat extravagant, for counter- terrorism has historically been barren ground for the flourishing of human rights. A more evident product of counter-terrorism is its baleful litany of atrocities and abuses, which include numerous British misdeeds in Ireland, such as Bloody Sunday in 1972 (Bloody Sunday Inquiry, 2009), and the more recent abuses of prisoners in Iraq (Baha Mousa Inquiry, 2010) or involvement in unlawful rendition (Gibson, 2013). Yet, the thesis adopted in this paper is that rights protection within counter-terrorism has strengthened since the entry into force (in October 2000) of the Human Rights Act 1998 in the United Kingdom. -

Constellation Legends

Constellation Legends by Norm McCarter Naturalist and Astronomy Intern SCICON Andromeda – The Chained Lady Cassiopeia, Andromeda’s mother, boasted that she was the most beautiful woman in the world, even more beautiful than the gods. Poseidon, the brother of Zeus and the god of the seas, took great offense at this statement, for he had created the most beautiful beings ever in the form of his sea nymphs. In his anger, he created a great sea monster, Cetus (pictured as a whale) to ravage the seas and sea coast. Since Cassiopeia would not recant her claim of beauty, it was decreed that she must sacrifice her only daughter, the beautiful Andromeda, to this sea monster. So Andromeda was chained to a large rock projecting out into the sea and was left there to await the arrival of the great sea monster Cetus. As Cetus approached Andromeda, Perseus arrived (some say on the winged sandals given to him by Hermes). He had just killed the gorgon Medusa and was carrying her severed head in a special bag. When Perseus saw the beautiful maiden in distress, like a true champion he went to her aid. Facing the terrible sea monster, he drew the head of Medusa from the bag and held it so that the sea monster would see it. Immediately, the sea monster turned to stone. Perseus then freed the beautiful Andromeda and, claiming her as his bride, took her home with him as his queen to rule. Aquarius – The Water Bearer The name most often associated with the constellation Aquarius is that of Ganymede, son of Tros, King of Troy.