HJS 'Defending Europe' Global Britain Report.Qxd 01/06/2018 18:34 Page 23

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Thompson, Mark S. (2009) the Rise of the Scientific Soldier As Seen Through the Performance of the Corps of Royal Engineers During the Early 19Th Century

Thompson, Mark S. (2009) The Rise of the Scientific Soldier as Seen Through the Performance of the Corps of Royal Engineers During the Early 19th Century. Doctoral thesis, University of Sunderland. Downloaded from: http://sure.sunderland.ac.uk/3559/ Usage guidelines Please refer to the usage guidelines at http://sure.sunderland.ac.uk/policies.html or alternatively contact [email protected]. THE RISE OF THE SCIENTIFIC SOLDIER AS SEEN THROUGH THE PERFORMANCE OF THE CORPS OF ROYAL ENGINEERS DURING THE EARLY 19TH CENTURY. Mark S. Thompson. A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the University of Sunderland for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. February 2009 TABLE OF CONTENTS. Table of Contents.................................................................................................ii Tables and Figures. ............................................................................................iii List of Appendices...............................................................................................iv Abbreviations .....................................................................................................v Abstract ....................................................................................................vi Acknowledgements............................................................................................vii SECTION 1. INTRODUCTION......................................................................... 1 1.1. Context ................................................................................................. -

Famous Bear Death Raises Larger Questions

July 8 - 21, 2016 Volume 7 // Issue #14 New West: Famous bear death raises larger questions Bullock, Gianforte debate in Big Sky A glimpse into the 2016 fire season Paddleboarding then and now Inside Yellowstone Caldera Plus: Guide to mountain biking Big Sky #explorebigsky explorebigsky explorebigsky @explorebigsky ON THE COVER: Famous grizzly 399 forages for biscuitroot on June 6 in a meadow along Pilgrim Creek as her cub, known as Snowy, peeks out from the safety of her side. Less than two weeks later this precocious cub was hit and killed by a car in Grand Teton National Park. PHOTO BY THOMAS D. MANGELSEN July 8-21, 2016 Volume 7, Issue No. 14 Owned and published in Big Sky, Montana TABLE OF CONTENTS PUBLISHER Eric Ladd Section 1: News New West: EDITORIAL Famous bear death EDITOR / EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR, MEDIA Opinion.............................................................................5 Joseph T. O’Connor raises larger questions Local.................................................................................6 SENIOR EDITOR/ DISTRIBUTION DIRECTOR Regional.........................................................................12 Tyler Allen Montana.........................................................................16 ASSOCIATE EDITOR Amanda Eggert Section 2: Environment, Sports, & Health CREATIVE SENIOR DESIGNER Taylor-Ann Smith Environment..................................................................17 GRAPHIC DESIGNER Sports.............................................................................21 Carie Birkmeier -

The Royal Engineers Journal

_ _I_·_ 1__ I _ _ _ __ ___ The Royal Engineers Journal. Sir Charles Paley . Lieut.-Col. P. H. Keay 77 Maintenance of Landing Grounds . A. Lewis-Dale, Esq. 598 The Combined Display, Royal Tournament, 1930 Bt. Lieut.-Col. N. T. Fitzpatrik 618 Restoration of Whitby Water Supply . Lieut. C. E. Montagu 624 Notes on the Engineers in the U.S. Army . "Ponocrates" 629 A Subaltern in the Indian Mutiny, Part I . Bt. CoL C. B. Thackeray 683 The Kelantan Section of the East Coast Railway, F.M.S.R. Lieut. Ll. Wansbrough-Jones 647 The Reconstruction of Tidworth Bridge by the 17th Field Company, R.E., in April, 1930 . Lient. W. B. Sallitt 657 The Abor Military and Political Mission, 1912-13. Part m. Capt. P. G. Huddlestcn 667 Engineer Units of the Officers' Training Corps . Major D. Portway 676 Some Out-of-the-Way Places .Lieut.-CoL L. E. Hopkins 680 " Pinking" . Capt. K. A. Lindsay 684 Office Organization in a Small Unit . Lieut. A. J. Knott 691 The L.G.O.C. Omnibus Repair Workshop at Chiswick Park Bt. Major G. MacLeod Ross 698 Sir Theo d'O Lite and the Dragon .Capt. J. C. T. Willis 702 Memoirs.-Wing-Commander Bernard Edward Smythies, Lieut.-Col. Sir John Norton-Griffiths . 705 Sixty Years Ago. 0 Troop-Retirement Scheme. 712 Books. Magazines. Correspondence. 714 VOL. XLIV. DECEMBER, 1930. CHATHAM: Tun INSTITUTION OF ROYAL ENGINZZBS. TZLEPHONZ: CHATHAM, 2669. AGZNTS AND PRINTERS: MACZAYS LTD. All it tt EXPAMET EXPANDED METAL Specialities "EXPAMET" STEEL SHEET REINFORCEMENT FOR CONCRETE. "EXPAMET" and "BB" LATHINGS FOR PLASTERWORK. -

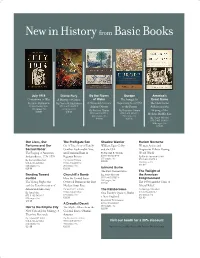

New in History from Basic Books

New in History from Basic Books July 1914 Divine Fury By the Rivers Europe America's Countdown to War A History of Genius of Water e Struggle for Great Game By Sean McMeekin By Darrin M. McMahon A Nineteenth-Century Supremacy, from 1453 e CIA’s Secret 978-0-465-03145-0 9 78-0-465-00325-9 Atlantic Odyssey to the Present Arabists and the 480 pages / hc 360 pages / hc By Erskine Clarke By Brendan Simms $29.99 $29.99 Shaping of the 978-0-465-00272-6 978-0-465-01333-3 Modern Middle East 488 pages / hc 720 pages / hc $29.99 $35.00 By Hugh Wilford 978-0-465-01965-6 384 pages / hc $29.99 Our Lives, Our The Profl igate Son Shadow Warrior Harlem Nocturne Fortunes and Our Or, A True Story of Family William Egan Colby Women Artists and Sacred Honor Con ict, Fashionable Vice, and the CIA Progressive Politics During e Forging of American and Financial Ruin in By Randall B. Woods World War II Independence, 1774-1776 Regency Britain 978-0-465-02194-9 By Farah Jasmine Griffi n 576 pages / hc By Nicola Phillips 978-0-465-01875-8 By Richard Beeman $29.99 978-0-465-02629-6 978-0-465-00892-6 264 pages / hc 528 pages / hc 360 pages / hc $26.99 $29.99 $28.99 Edmund Burke e First Conservative The Twilight of Bending Toward Churchill’s Bomb By Jesse Norman the American How the United States 978-0-465-05897-6 Justice 336 pages / hc Enlightenment e Voting Rights Act Overtook Britain in the First $27.99 e 1950s and the Crisis of and the Transformation of Nuclear Arms Race Liberal Belief American Democracy By Graham Farmelo The Rainborowes By George Marsden By Gary May 978-0-465-02195-6 One Family’s Quest to Build 978-0-465-03010-1 576 pages / hc 240 pages / hc 978-0-465-01846-8 a New England 336 pages / hc $29.99 $26.99 $28.99 By Adrian Tinniswood 978-0-465-02300-4 A Dreadful Deceit 384 pages / hc Heir to the Empire City e Myth of Race from the $28.99 New York and the Making of Colonial Era to Obama’s eodore Roosevelt America By Edward P. -

Serviceplus 1/2015 PDF (8.81

The Dussmann Group magazine Edition Summer 2015 Summer Edition Ausgabe Sommer 2015 Sommer Ausgabe XGLOBALX The EXPO Milano 2015— feeding the planet, energy for life XRESEARCH OrIENTEDX Roche—a health care company with pharmaceuticals and diagnostics XINNOVATION ORIENTEDX Altana—solutions for paint manufacturers and many other industries Editorial 10 Dear Reader, In today’s changing world, it is easy to forget that there is one thing that hasn’t changed: that our economic system is all about creating value. Put simply, this means transforming existing goods to increase their monetary value. Industry plays a decisive role. This sec- tion of the economy processes and produces material goods, often with highly automated technology. From our dialogue with industrial clients, we are aware that development and improvement of the produc- 4 12 tion chain requires continuous innovation and this commands their full attention. The transition from an industrial economy to a service-oriented economy is not the only issue, as some would have us believe. Rather, it is service providers such as the Dussmann Group who can support manufacturers in their quest to improve the value chain. Contents In this issue of Serviceplus, we introduce some of our industrial clients. We would be happy to introduce our sector-specific concepts for the food, pharmaceu- tical or semi-conductor industries, personally if you FOCUS: INDUSTRY wish. Experience has shown that cooperation between an industrial client and a service provider can lead to 4 Some Like it Simple extremely efficient, innovative value creation concepts. SKW Piesteritz is Germany’s biggest producer We are convinced that there would be little need for of ammonia and urea products and an attrac- highly specialized services without competitive manu- tive employer, among other reasons, because facturers and the added value that they generate. -

Health Systems Research ______

Health Systems Research ______ D. Schwefel R. Leidl J. Rovira M. F Drummond (Eds.) HEALTH SYSTEMS RESEARCH Edited by K. Davis and W. van Eimeren Detlef Schwefel Reiner Leidl Joan Rovira Michael F. Drummond (Eds.) Economic Aspects of AIDS and HIV Infection With 66 Figures and 69 Tables Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg New York London Paris Tokyo Hong Kong ("' -- I J-5 & ) 0 ,-i-·1.- ~ (.,' I\,'~ c i t , l I :::.J ... Professor Dr. Detlef Schwefel GSF-Institut fur Medizinische Informatik und Systemforschung IngolsUidter LandstraBe 1, 8042 Neuherberg, FRG Dr. Reiner Leidl GSF-Institut fiir Medizinische Informatik und Systemforschung Ingolstadter LandstraBe 1, 8042 Neuherberg, FRG Professor Dr. Joan Rovira Department de Teoria Economica, Universitat de Barcelona Av. Diagonal690, Barcelona 0834, Spain Professor Dr. Michael F. Drummond Health Services Management Centre, The University of Birmingham Park House Edgbaston Park Road, Birmingham, B15 2RT, UK Publication No. EUR 12565 of the Scientific and Technical Communication Unit, Commission of the European Communities, Directorate-General Telecommunications, Information Indus tries and Innovation, Luxembourg Legal notice: Neither the Commission of the European Communities nor any person acting on behalf of the Commission is responsible for the use which might be made of the following information. ISBN 3-540-52135-6 Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg New York ISBN G-387-52135-6 Springer-Verlag New York Berlin Heidelberg Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Economic aspects of AIDS and HIV infection I Detlef Schwefel ... [eta!.], eds. p. cm.-(Health systems research) "On behalf of the Concerted Action Committee (COMAC) on Health Services Research (HSR), the GSF-Institut fur Medizinische lnformatik und Systemforschung (MEDIS) convened an international conference .. -

Military Aspects of Hydrogeology: an Introduction and Overview

Downloaded from http://sp.lyellcollection.org/ by guest on September 28, 2021 Military aspects of hydrogeology: an introduction and overview JOHN D. MATHER* & EDWARD P. F. ROSE Department of Earth Sciences, Royal Holloway, University of London, Egham, Surrey TW20 0EX, UK *Corresponding author (e-mail: [email protected]) Abstract: The military aspects of hydrogeology can be categorized into five main fields: the use of groundwater to provide a water supply for combatants and to sustain the infrastructure and defence establishments supporting them; the influence of near-surface water as a hazard affecting mobility, tunnelling and the placing and detection of mines; contamination arising from the testing, use and disposal of munitions and hazardous chemicals; training, research and technology transfer; and groundwater use as a potential source of conflict. In both World Wars, US and German forces were able to deploy trained hydrogeologists to address such problems, but the prevailing attitude to applied geology in Britain led to the use of only a few, talented individuals, who gained relevant experience as their military service progressed. Prior to World War II, existing techniques were generally adapted for military use. Significant advances were made in some fields, notably in the use of Norton tube wells (widely known as Abyssinian wells after their successful use in the Abyssinian War of 1867/1868) and in the development of groundwater prospect maps. Since 1945, the need for advice in specific military sectors, including vehicle mobility, explosive threat detection and hydrological forecasting, has resulted in the growth of a group of individuals who can rightly regard themselves as military hydrogeologists. -

Rsme Matters

G N I R E E N I G N E Y R A T I L I M rsme F O L O O H C S L A Y matters O R E ISSUE 3 : NOVEMBER 2009 H T M O R F S W E N Inside: Learning Lessons in Afghanistan Working together to train our soldiers for operations NOVEMBER 2009 03 rsme matters Contents Features Introduction ............................................4 6 8 New CO for 1 RSME ...............................4 Safety Update .........................................5 Open Day ................................................6 The Class of 2009 – Sapper Volunteers ..................................8 OPEN DAY THE CLASS OF 2009 – Thousands of people crowded into SAPPER VOLUNTEERS Army Show and Trade Village ...............10 Brompton Barracks for the RSME RSME Matters has enlisted the help Open Day. The afternoon was a of 6 willing volunteer sappers and Look at Life ...........................................11 great success with both the arena will follow them from the basic B3 events and the display areas Combat Engineering training through Medway Recce .....................................11 proving equally popular... their trade training and on into the Read more on page 6 field army... Read more on page 8 Construction Update: ...........................12 Eco Greenhouse ...................................13 Learning Lessons in Afghanistan .........14 11 Padre Pat Aldred ..................................16 Veterans at Chatham and Memorial Service ...........................16 Top Bucket 2009 ..................................17 Sky High for Charity .............................18 -

The Junior British Army Officer: Experience and Identity, 1793-1815

The Junior British Army Officer: Experience and Identity, 1793-1815 by David Lachlan Huf, B.A. (Hons) School of Humanities (History) Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy, Arts University of Tasmania, June 2017 ii Declaration of Originality This thesis contains no material which has been accepted for a degree or diploma by the University or any other institution, except by way of background information and duly acknowledged in the thesis, and to the best of my knowledge and belief, no material previously published or written by another person except where due acknowledgement is made in the test of the thesis, nor does this thesis contain any material that infringes copyright. Signed ………………… Date 07/06/2017 Declaration of Authority to Access This thesis is not to be made available for loan or copying for two years following the date this statement was signed. Following that time, the thesis may be made available for loan and limited copying and communication in accordance with the Copyright Act 1968. Signed ………………… Date 07/06/2017 iii Acknowledgements This thesis is the culmination of an eight-year association with the University of Tasmania, where I started studying as an undergraduate in 2009. The number of people and institutions who I owe the deepest gratitude to during my time with the university and especially during the completion of my thesis is vast. In Gavin Daly and Anthony Page, I am privileged to have two supervisors who are so accomplished in eighteenth-century British history, and the history of the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic era. -

Thompson, Mark S. (2009) the Rise of the Scientific Soldier As Seen Through the Performance of the Corps of Royal Engineers During the Early 19Th Century

Thompson, Mark S. (2009) The Rise of the Scientific Soldier as Seen Through the Performance of the Corps of Royal Engineers During the Early 19th Century. Doctoral thesis, University of Sunderland. Downloaded from: http://sure.sunderland.ac.uk/id/eprint/3559/ Usage guidelines Please refer to the usage guidelines at http://sure.sunderland.ac.uk/policies.html or alternatively contact [email protected]. THE RISE OF THE SCIENTIFIC SOLDIER AS SEEN THROUGH THE PERFORMANCE OF THE CORPS OF ROYAL ENGINEERS DURING THE EARLY 19TH CENTURY. Mark S. Thompson. A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the University of Sunderland for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. February 2009 TABLE OF CONTENTS. Table of Contents.................................................................................................ii Tables and Figures. ............................................................................................iii List of Appendices...............................................................................................iv Abbreviations .....................................................................................................v Abstract ....................................................................................................vi Acknowledgements............................................................................................vii SECTION 1. INTRODUCTION......................................................................... 1 1.1. Context ................................................................................................. -

5C Defence Heritage – Napoleonic

EB 11.15c PROJECT: Shepway Heritage Strategy DOCUMENT NAME: Theme 5c: Defence Heritage - Napoleonic Version Status Prepared by Date V01 INTERNAL DRAFT B Found 13/10/16 Comments – First draft of text. No illustrations. Needs current activities added and opportunities updated. Version Status Prepared by Date V02 Version Status Prepared by Date V03 Version Status Prepared by Date V03 Version Status Prepared by Date V04 Version Status Prepared by Date V05 5c Defence Heritage – Napoleonic 1 Summary Shepway contains an exceptionally significant collection of Napoleonic period fortifications. Notable works of this period include the great programme of Martello building, construction of the Grand Redoubt at Dymchurch and the cutting of the Royal Military Canal. The collection of Napoleonic period defences in Shepway District form a group of sites of outstanding importance. 2 Overview 2.1 Background The French Revolution of 1789 and the deposition of Louis XVI of France sent shockwaves across the whole of Europe and ultimately saw war spread across Europe and the overseas colonies. Throughout this period Britain was engaged almost continuously in wars with France, ending ultimately with the defeat of Napoleon. The outbreak of the Revolutionary Wars (1793-1802) and subsequent Napoleonic Wars (1803 – 1815) saw an extensive system of new defences built in stages across the district. At the start of this period Britain was primarily a maritime nation, with only a small standing army. Naval supremacy was Britain’s traditional first line of defence; by controlling the channel and blockading the French fleet in its ports the Admiralty was confident that it could protect Britain from invasion. -

Zeitenwende | Wendezeiten

Zeitenwende Wendezeiten Special Edition of the Munich Security Report on German Foreign and Security Policy October 2020 October 2020 Zeitenwende | Wendezeiten Special Edition of the Munich Security Report on German Foreign and Security Policy Tobias Bunde Laura Hartmann Franziska Stärk Randolf Carr Christoph Erber Julia Hammelehle Juliane Kabus With guest contributions by Elbridge Colby, François Heisbourg, Toomas Hendrik Ilves, Andrey Kortunov, Shivshankar Menon, David Miliband, Ana Palacio, Kevin Rudd, Anne-Marie Slaughter, Nathalie Tocci, and Huiyao Wang. Table of Contents Foreword 4 Foreword by former Federal President Joachim Gauck 8 Executive Summary 11 1 Introduction: The Munich Consensus 17 2 Security Situation: Zeitenwende 26 3 Dependencies: Wonderful Together, 50 Vulnerable Together 4 Investments: Instrumental Reasoning 74 5 Public Opinion: Folk Wisdom 106 6 Decision-making Processes: Berlin Disharmonic 144 7 Outlook: Wendezeiten 166 Notes 176 Endnotes 177 List of Figures 203 Image Sources 210 List of Abbreviations 211 Team 214 Acknowledgments 215 Imprint 217 ZEITENWENDE | WENDEZEITEN Foreword Dear Reader, In recent years, the Munich Security Conference (MSC) has highlighted a wide variety of security policy issues at its events in all corners of the world – from Madrid to Minsk, from Tel Aviv to New York, from Abuja Wolfgang Ischinger to Stavanger. In doing so, we focused primarily on international challenges. At our events, however, we were increasingly confronted with questions about Germany’s positions – sometimes with fear and unease about whether Berlin was, for example, taking certain threats seriously enough – but almost always with great expectations of our country. At home, on the other hand, people still regularly underestimate how important our country is now considered to be almost everywhere in the world.