Spinner (1938-2018)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Summary of Petroleum Plays and Characteristics of the Michigan Basin

DEPARTMENT OF INTERIOR U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY A summary of petroleum plays and characteristics of the Michigan basin by Ronald R. Charpentier Open-File Report 87-450R This report is preliminary and has not been reviewed for conformity with U.S. Geological Survey editorial standards and stratigraphic nomenclature. Denver, Colorado 80225 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ABSTRACT.................................................. 3 INTRODUCTION.............................................. 3 REGIONAL GEOLOGY.......................................... 3 SOURCE ROCKS.............................................. 6 THERMAL MATURITY.......................................... 11 PETROLEUM PRODUCTION...................................... 11 PLAY DESCRIPTIONS......................................... 18 Mississippian-Pennsylvanian gas play................. 18 Antrim Shale play.................................... 18 Devonian anticlinal play............................. 21 Niagaran reef play................................... 21 Trenton-Black River play............................. 23 Prairie du Chien play................................ 25 Cambrian play........................................ 29 Precambrian rift play................................ 29 REFERENCES................................................ 32 LIST OF FIGURES Figure Page 1. Index map of Michigan basin province (modified from Ells, 1971, reprinted by permission of American Association of Petroleum Geologists)................. 4 2. Structure contour map on top of Precambrian basement, Lower Peninsula -

Copper Deposits in Sedimentary and Volcanogenic Rocks

Copper Deposits in Sedimentary and Volcanogenic Rocks GEOLOGICAL SURVEY PROFESSIONAL PAPER 907-C COVER PHOTOGRAPHS 1 . Asbestos ore 8. Aluminum ore, bauxite, Georgia 1 2 3 4 2. Lead ore. Balmat mine, N . Y. 9. Native copper ore, Keweenawan 5 6 3. Chromite-chromium ore, Washington Peninsula, Mich. 4. Zinc ore, Friedensville, Pa. 10. Porphyry molybdenum ore, Colorado 7 8 5. Banded iron-formation, Palmer, 11. Zinc ore, Edwards, N.Y. Mich. 12. Manganese nodules, ocean floor 9 10 6. Ribbon asbestos ore, Quebec, Canada 13. Botryoidal fluorite ore, 11 12 13 14 7. Manganese ore, banded Poncha Springs, Colo. rhodochrosite 14. Tungsten ore, North Carolina Copper Deposits in Sedimentary and Volcanogenic Rocks By ELIZABETH B. TOURTELOT and JAMES D. VINE GEOLOGY AND RESOURCES OF COPPER DEPOSITS GEOLOGICAL SURVEY PROFESSIONAL PAPER 907-C A geologic appraisal of low-temperature copper deposits formed by syngenetic, diagenetic, and epigenetic processes UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE, WASHINGTON : 1976 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR THOMAS S. KLEPPE, Secretary GEOLOGICAL SURVEY V. E. McKelvey, Director First printing 1976 Second printing 1976 Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Tourtelot, Elizabeth B. Copper deposits in sedimentary and volcanogenic rocks. (Geology and resources of copper) (Geological Survey Professional Paper 907-C) Bibliography: p. Supt. of Docs. no.: I 19.16:907-C 1. Copper ores. 2. Rocks, Sedimentary. 3. Rocks, Igneous. I. Vine, James David, 1921- joint author. II. Title. III. Series. IV. Series: United States Geological Survey Professional Paper 907-C. TN440.T68 553'.43 76-608039 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. -

Summary of Hydrogelogic Conditions by County for the State of Michigan. Apple, B.A., and H.W. Reeves 2007. U.S. Geological Surve

In cooperation with the State of Michigan, Department of Environmental Quality Summary of Hydrogeologic Conditions by County for the State of Michigan Open-File Report 2007-1236 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey Summary of Hydrogeologic Conditions by County for the State of Michigan By Beth A. Apple and Howard W. Reeves In cooperation with the State of Michigan, Department of Environmental Quality Open-File Report 2007-1236 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Department of the Interior DIRK KEMPTHORNE, Secretary U.S. Geological Survey Mark D. Myers, Director U.S. Geological Survey, Reston, Virginia: 2007 For more information about the USGS and its products: Telephone: 1-888-ASK-USGS World Wide Web: http://www.usgs.gov/ Any use of trade, product, or firm names in this publication is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. Although this report is in the public domain, permission must be secured from the individual copyright owners to reproduce any copyrighted materials contained within this report. Suggested citation Beth, A. Apple and Howard W. Reeves, 2007, Summary of Hydrogeologic Conditions by County for the State of Michi- gan. U.S. Geological Survey Open-File Report 2007-1236, 78 p. Cover photographs Clockwise from upper left: Photograph of Pretty Lake by Gary Huffman. Photograph of a river in winter by Dan Wydra. Photographs of Lake Michigan and the Looking Glass River by Sharon Baltusis. iii Contents Abstract ...........................................................................................................................................................1 -

Paleozoic Stratigraphic Nomenclature for Wisconsin (Wisconsin

UNIVERSITY EXTENSION The University of Wisconsin Geological and Natural History Survey Information Circular Number 8 Paleozoic Stratigraphic Nomenclature For Wisconsin By Meredith E. Ostrom"'" INTRODUCTION The Paleozoic stratigraphic nomenclature shown in the Oronto a Precambrian age and selected the basal contact column is a part of a broad program of the Wisconsin at the top of the uppermost volcanic bed. It is now known Geological and Natural History Survey to re-examine the that the Oronto is unconformable with older rocks in some Paleozoic rocks of Wisconsin and is a response to the needs areas as for example at Fond du Lac, Minnesota, where of geologists, hydrologists and the mineral industry. The the Outer Conglomerate and Nonesuch Shale are missing column was preceded by studies of pre-Cincinnatian cyclical and the younger Freda Sandstone rests on the Thompson sedimentation in the upper Mississippi valley area (Ostrom, Slate (Raasch, 1950; Goldich et ai, 1961). An unconformity 1964), Cambro-Ordovician stratigraphy of southwestern at the upper contact in the Upper Peninsula of Michigan Wisconsin (Ostrom, 1965) and Cambrian stratigraphy in has been postulated by Hamblin (1961) and in northwestern western Wisconsin (Ostrom, 1966). Wisconsin wlle're Atwater and Clement (1935) describe un A major problem of correlation is the tracing of outcrop conformities between flat-lying quartz sandstone (either formations into the subsurface. Outcrop definitions of Mt. Simon, Bayfield, or Hinckley) and older westward formations based chiefly on paleontology can rarely, if dipping Keweenawan volcanics and arkosic sandstone. ever, be extended into the subsurface of Wisconsin because From the above data it would appear that arkosic fossils are usually scarce or absent and their fragments cari rocks of the Oronto Group are unconformable with both seldom be recognized in drill cuttings. -

The End of Midcontinent Rift Magmatism and the Paleogeography of Laurentia

THEMED ISSUE: Tectonics at the Micro- to Macroscale: Contributions in Honor of the University of Michigan Structure-Tectonics Research Group of Ben van der Pluijm and Rob Van der Voo The end of Midcontinent Rift magmatism and the paleogeography of Laurentia Luke M. Fairchild1, Nicholas L. Swanson-Hysell1, Jahandar Ramezani2, Courtney J. Sprain1, and Samuel A. Bowring2 1DEPARTMENT OF EARTH AND PLANETARY SCIENCE, UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, BERKELEY, CALIFORNIA 94720, USA 2DEPARTMENT OF EARTH, ATMOSPHERIC AND PLANETARY SCIENCES, MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY, CAMBRIDGE, MASSACHUSETTS 02139, USA ABSTRACT Paleomagnetism of the North American Midcontinent Rift provides a robust paleogeographic record of Laurentia (cratonic North America) from ca. 1110 to 1070 Ma, revealing rapid equatorward motion of the continent throughout rift magmatism. Existing age and paleomagnetic constraints on the youngest rift volcanic and sedimentary rocks have been interpreted to record a slowdown of this motion as rifting waned. We present new paleomagnetic and geochronologic data from the ca. 1090–1083 Ma “late-stage” rift volcanic rocks exposed as the Lake Shore Traps (Michigan), the Schroeder-Lutsen basalts (Minnesota), and the Michipicoten Island Formation (Ontario). The paleomagnetic data allow for the development of paleomagnetic poles for the Schroeder-Lutsen basalts (187.8°E, 27.1°N; A95 = 3.0°, N = 50) and the Michipicoten Island Formation (174.7°E, 17.0°N; A95 = 4.4°, N = 23). Temporal constraints on late-stage paleomagnetic poles are provided by high-precision, 206Pb-238U zircon dates from a Lake Shore Traps andesite (1085.57 ± 0.25 Ma; 2σ internal errors), a Michipicoten Island Formation tuff (1084.35 ± 0.20 Ma) and rhyolite (1083.52 ± 0.23 Ma), and a Silver Bay aplitic dike from the Beaver Bay Complex (1091.61 ± 0.14 Ma), which is overlain by the Schroeder-Lutsen basalt flows. -

Geology of Michigan and the Great Lakes

35133_Geo_Michigan_Cover.qxd 11/13/07 10:26 AM Page 1 “The Geology of Michigan and the Great Lakes” is written to augment any introductory earth science, environmental geology, geologic, or geographic course offering, and is designed to introduce students in Michigan and the Great Lakes to important regional geologic concepts and events. Although Michigan’s geologic past spans the Precambrian through the Holocene, much of the rock record, Pennsylvanian through Pliocene, is miss- ing. Glacial events during the Pleistocene removed these rocks. However, these same glacial events left behind a rich legacy of surficial deposits, various landscape features, lakes, and rivers. Michigan is one of the most scenic states in the nation, providing numerous recre- ational opportunities to inhabitants and visitors alike. Geology of the region has also played an important, and often controlling, role in the pattern of settlement and ongoing economic development of the state. Vital resources such as iron ore, copper, gypsum, salt, oil, and gas have greatly contributed to Michigan’s growth and industrial might. Ample supplies of high-quality water support a vibrant population and strong industrial base throughout the Great Lakes region. These water supplies are now becoming increasingly important in light of modern economic growth and population demands. This text introduces the student to the geology of Michigan and the Great Lakes region. It begins with the Precambrian basement terrains as they relate to plate tectonic events. It describes Paleozoic clastic and carbonate rocks, restricted basin salts, and Niagaran pinnacle reefs. Quaternary glacial events and the development of today’s modern landscapes are also discussed. -

Annual Meeting 2014

The Palaeontological Association 58th Annual Meeting 16th–19th December 2014 University of Leeds PROGRAMME abstracts and AGM papers Public transport to the University of Leeds BY TRAIN: FROM TRAIN STATION ON FOOT: Leeds Train Station links regularly to all major UK cities. You The University campus is a 20 minute walk from the train can get from the station to the campus on foot, by taxi or by station. The map below will help you find your way. bus. A taxi ride will take about 10 minutes and it will cost Leave the station through the exit facing the main concourse. approximately £5. Turn left past the bus stops and walk down towards City Square. Keeping City Square on your left, walk straight up FROM TRAIN STATION BY BUS: Park Row. At the top of the road turn right onto The Headrow, We advise you to take bus number 1 which departs from passing The Light shopping centre on your left. After The Light Infirmary Street. The bus runs approximately every 10 minutes turn left onto Woodhouse Lane to continue uphill. Keep going, and the journey takes 10 minutes. passing Morrisons, Leeds Metropolitan and the Dry Dock You should get off the bus just outside the Parkinson Building. boat pub heading for the large white clock tower. This is the (There is also the £1 Leeds City Bus which takes you from the Parkinson building. train station to the lower end of campus but the journey time is much longer). BY COACH: If you arrive by coach you can catch bus numbers 6,28 or 97 to the University (Parkinson Building). -

MIDCONTINENT RIFT SYSTEM BIBLIOGRAPHY by Steven A

MIDCONTINENT RIFT SYSTEM BIBLIOGRAPHY By Steven A. Hauck December 1995 Technical Report NRRI/TR-95/33 Funded by the Natural Resources Research Institute In Preparation for the 1995 International Geological Correlation Program Project 336 Field Conference in Duluth, MN Natural Resources Research Institute University of Minnesota, Duluth 5013 Miller Trunk Highway Duluth, MN 55811-1442 TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ................................................... 1 THE DATABASE .............................................. 1 Use of the PAPYRUS Retriever Program (Diskette) .............. 3 Updates, Questions, Comments, Etc. ......................... 3 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ....................................... 4 MIDCONTINENT RIFT SYSTEM BIBLIOGRAPHY ......................... 5 AUTHOR INDEX ................................................. 191 KEYWORD INDEX ................................................ 216 i This page left blank intentionally. ii INTRODUCTION The co-chairs of the IGCP Project 336 field conference on the Midcontinent Rift System felt that a comprehensive bibliography of articles relating to a wide variety of subjects would be beneficial to individuals interested in, or working on, the Midcontinent Rift System. There are 2,543 references (>4.2 MB) included on the diskette at the back of this volume. PAPYRUS Bibliography System software by Research Software Design of Portland, Oregon, USA, was used in compiling the database. A retriever program (v. 7.0.011) for the database was provided by Research Software Design for use with the database. The retriever program allows the user to use the database without altering the contents of the database. However, the database can be used, changed, or augmented with a complete version of the program (ordering information can be found in the readme file). The retriever program allows the user to search the database and print from the database. The diskette contains compressed data files. -

Oxygenated Mesoproterozoic Lake Revealed Through Magnetic

Oxygenated Mesoproterozoic lake revealed through magnetic mineralogy Sarah P. Slotznicka,1, Nicholas L. Swanson-Hysella, and Erik A. Sperlingb aDepartment of Earth and Planetary Science, University of California, Berkeley, CA 94720; and bDepartment of Geological Sciences, Stanford University, Stanford, CA 94305 Edited by Paul F. Hoffman, University of Victoria, Victoria, BC, Canada, and approved October 29, 2018 (received for review August 4, 2018) Terrestrial environments have been suggested as an oxic haven Formation has been further interpreted to indicate the pres- for eukaryotic life and diversification during portions of the Pro- ence of more than 50 different species (4). This record is terozoic Eon when the ocean was dominantly anoxic. However, argued to be more diverse than similar-aged marine assemblages, iron speciation and Fe/Al data from the ca. 1.1-billion-year-old which leads to the interpretation that lacustrine environments Nonesuch Formation, deposited in a large lake and bearing a with stable oxygenated waters may have been more hospitable diverse assemblage of early eukaryotes, are interpreted to indi- to eukaryotic evolution than marine ones (4). Early oxygena- cate persistently anoxic conditions. To shed light on these distinct tion of lacustrine environments during the Mesoproterozoic hypotheses, we analyzed two drill cores spanning the trans- has also been proposed based on large sulfur isotope frac- gression into the lake and its subsequent shallowing. While the tionations from sedimentary rocks of the Stoer and Torridon proportion of highly reactive to total iron (FeHR/FeT) is consis- groups that were interpreted to have resulted from oxidative tent through the sediments and typically in the range taken sulfur cycling (15). -

Contents Illustrations Table Introduction

The Base of the Upper Keweenawan, ILLUSTRATIONS Michigan and Wisconsin FIGURE 1. Distribution of the Copper Harbor Conglomerate and included mafic lava members...........................................2 By WALTER S. WHITE 2. Stratigraphic section of the Copper Harbor Conglomerate..2 CONTRIBUTIONS TO STRATIGRAPHY 3. Longitudinal stratigraphic section of Keweenawan rocks below the base of the Nonesuch Shale............................3 4. Mean directions of magnetization for some Keweenawan GEOLOGICAL SURVEY BULLETIN 1354-F rocks.. ..............................................................................6 A proposal to adopt the top of the Copper Harbor 5. Proposed nomenclature for middle and upper Keweenawan Conglomerate as the base of the upper Keweenawan in rocks ................................................................................9 the Lake Superior region TABLE TABLE 1. Compressional wave velocities (km/sec) for selected Keweenawan stratigraphic units, Lake Superior region ...7 ABSTRACT UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE, The top of the Copper Harbor Conglomerate (base of WASHINGTON : 1972 Nonesuch Shale) is a more satisfactory boundary between upper and middle Keweenawan rocks in northern Michigan and UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR adjacent parts of Wisconsin than the various horizons that ROGERS G. B. MORTON, Secretary have been used hitherto without stratigraphic consistency from GEOLOGICAL SURVEY place to place. Irving’s original boundary (1883) cannot be V. E. McKelvey, Director followed away from the Keweenaw Peninsula. The top of the Copper Harbor Conglomerate comes closer to marking the Library of Congress catalog-card No. 72-75175 close of Keweenawan volcanism than other major boundaries and actually adheres more closely to Irving’s original concept For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office than the boundary that he himself chose. -

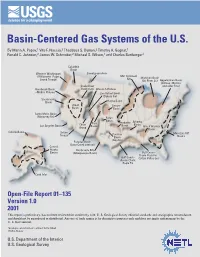

Basin-Centered Gas Systems of the U.S. by Marin A

Basin-Centered Gas Systems of the U.S. By Marin A. Popov,1 Vito F. Nuccio,2 Thaddeus S. Dyman,2 Timothy A. Gognat,1 Ronald C. Johnson,2 James W. Schmoker,2 Michael S. Wilson,1 and Charles Bartberger1 Columbia Basin Western Washington Sweetgrass Arch (Willamette–Puget Mid-Continent Rift Michigan Basin Sound Trough) (St. Peter Ss) Appalachian Basin (Clinton–Medina Snake River and older Fms) Hornbrook Basin Downwarp Wasatch Plateau –Modoc Plateau San Rafael Swell (Dakota Fm) Sacramento Basin Hanna Basin Great Denver Basin Basin Santa Maria Basin (Monterey Fm) Raton Basin Arkoma Park Anadarko Los Angeles Basin Chuar Basin Basin Group Basins Black Warrior Basin Colville Basin Salton Mesozoic Rift Trough Permian Basin Basins (Abo Fm) Paradox Basin (Cane Creek interval) Central Alaska Rio Grande Rift Basins (Albuquerque Basin) Gulf Coast– Travis Peak Fm– Gulf Coast– Cotton Valley Grp Austin Chalk; Eagle Fm Cook Inlet Open-File Report 01–135 Version 1.0 2001 This report is preliminary, has not been reviewed for conformity with U. S. Geological Survey editorial standards and stratigraphic nomenclature, and should not be reproduced or distributed. Any use of trade names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U. S. Government. 1Geologic consultants on contract to the USGS 2USGS, Denver U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey BASIN-CENTERED GAS SYSTEMS OF THE U.S. DE-AT26-98FT40031 U.S. Department of Energy, National Energy Technology Laboratory Contractor: U.S. Geological Survey Central Region Energy Team DOE Project Chief: Bill Gwilliam USGS Project Chief: V.F. -

Open File Report LXXX GEOLOGY of MICHIGAN

Open File Report LXXX Scenic Beauty of the Pre-Cambrian.............................13 Pre-Cambrian in Lower Michigan.................................14 GEOLOGY OF MICHIGAN X Paleozoic Era ..............................................................14 by Cambrian Period ..........................................................14 O. F. Poindexter The Michigan Basin ............................................... 14 Economic Products of the Cambrian..................... 15 1934 Formation, Sandstone, Shale, Limestone, Dolomite and Conglomerate ................................................. 15 Sandstone..................................................................15 TABLE OF CONTENTS Shale..........................................................................15 Limestone ..................................................................15 I Introduction and Acknowledgments ............................... 2 Dolomite.....................................................................15 Conglomerate.............................................................15 II Definition of Geology..................................................... 3 Scenic Effects of the Cambrian ............................. 15 III Origin of the Earth and Solar System .......................... 3 Ordovician Period.........................................................16 St. Peter Formation ............................................... 16 IV Composition of the Earth’s Core.................................. 4 Trenton Formation (Trenton-Black River).............