Retailing Scandal: the Disappearance of Friedrich Accum

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fredrick Accum: an Important Nineteenth-Century Chemist Fallen Into Oblivion

Bull. Hist. Chem., VOLUME 43, Number 2 (2018) 79 FREDRICK ACCUM: AN IMPORTANT NINETEENTH-CENTURY CHEMIST FALLEN INTO OBLIVION João Paulo André, Centro/Departamento de Química, Campus de Gualtar, Universidade do Minho, 4710 - 057 Braga, Portugal; [email protected] Abstract This paper presents the work and legacy of this controversial and once-famous chemist, including a The German-born Fredrick Accum (1769-1838), description of the events that precipitated his abrupt lecturer, author, analyst, industrial chemist, technical ex- departure from the international scene. pert and trader of chemicals and apparatus was once one of the best-known scientists in the United Kingdom. His Introduction efforts to popularize chemistry and to bring it to people of all classes were highly successful as demonstrated In the article “The Past and Future of the History by the large audiences of men and women that used to of Chemistry Division,” published in Journal of Chemi- fill the amphitheater of the Surrey Institution to attend cal Education in 1937, after noting the scientific and his public lectures. His books on chemistry, mineralogy, pedagogical achievements of the once-famous German crystallography and the use of gas for public and home chemist Fredrick Accum (Figure 1), its author, Charles illumination (of which he was an early promoter) were A. Browne, states that the latter “suffered the most so much appreciated that they were published in several tragic fate that can befall a scientist—that of going into editions and translated into various languages. Numerous sudden oblivion with a clouded reputation” (1). Eighty distinguished students learned their practical skills in his years after publication of that paper, the indifference private laboratory and school. -

Popular Astronomy Lectures in Nineteenth Century Britain

Commercial and Sublime: Popular Astronomy Lectures in Nineteenth Century Britain Hsiang-Fu Huang UCL Department of Science and Technology Studies Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) in History and Philosophy of Science March 2015 2 I, Hsiang-Fu Huang, confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated in the thesis. Date of signature: 9th March 2015 Supervisors: Joe Cain (UCL) Simon Werrett (UCL) Examiners: Frank A. J. L. James (UCL / Royal Institution of Great Britain) Richard Bellon (Michigan State University) Date of examination: 16th December 2014 3 4 Abstract This thesis discusses the practitioners, sites, curriculums, apparatus and audiences of popular astronomy lecturing in nineteenth-century Britain. Lecturers who were active approximately between 1820 and 1860 are the focus. This thesis emphasises popularisers who were not scientific elites, including C. H. Adams (1803-1871), George Bartley (c. 1782-1858), and D. F. Walker (1778-1865). Activities of private popularisers are compared with those in scientific establishments, such as the Royal Institution. Private entrepreneurs were not inferior to institutional competitors and enjoyed popularity among audiences. Until the 1860s, popular astronomy lecturing was a shared arena of institutional and private popularisers. A theatrical turn occurred in the popular astronomy lecturing trade before 1820. Popularisers moved lectures into theatres and adopted theatrical facilities in performance. They developed large onstage devices, such as the transparent orrery, for achieving scenic and dramatic effects. These onstage astronomical lectures were a phenomenon in the early nineteenth century and were usually performed during Lent. -

Bull. Hist. Chem. 11

Bull. is. Cem. 11 ( 79 In consequence of this decision, many of the references in the index to volumes 1-20, 1816-26, of the Quarterly Journal of interleaved copy bear no correspondence to anything in the text Science and the Arts, published in 1826, in the possession of of the revised editions, the Royal Institution, has added in manuscript on its title-page Yet Faraday continued to add references between the dates "Made by M. Faraday", Since the cumulative index was of the second and third editions, that is, between 1830 and largely drawn from the separate indexes of each volume, it is 1842, One of these is in Section XIX, "Bending, Bowing and likely that the recurrent task of making those was also under- Cutting of Glass", which begins on page 522. It is listed as taken by Faraday. If such were indeed the case, he would have "Grinding of Glass" and refers to Silliman's Journal, XVII, had considerable experience in that kind of harmless drudgery, page 345, The reference is to a paper by Elisha Mitchell, dating from the days when his position at the Royal Institution Professor of Chemistry, Mineralogy, &c. at the University of was still that of an assistant to William Brande. Carolina, entitled "On a Substitute for WeIdler's Tube of Safety, with Notices of Other Subjects" (11). This paper is frn nd t interesting as it contains a reference to Chemical Manipulation and a practical suggestion on how to cut glass with a hot iron . M. aaay, Chl Mnpltn n Intrtn t (11): Stdnt n Chtr, n th Mthd f rfrn Exprnt f ntrtn r f rh, th Ar nd S, iis, M. -

The Food Industry's Perception of Economically Motivated

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Masters Theses Graduate School 5-2016 The Food Industry’s Perception of Economically Motivated Adulteration and Related Risk Factors Lindsay Colleen Murphy University of Tennessee - Knoxville, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes Part of the Other Food Science Commons Recommended Citation Murphy, Lindsay Colleen, "The Food Industry’s Perception of Economically Motivated Adulteration and Related Risk Factors. " Master's Thesis, University of Tennessee, 2016. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes/3792 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a thesis written by Lindsay Colleen Murphy entitled "The Food Industry’s Perception of Economically Motivated Adulteration and Related Risk Factors." I have examined the final electronic copy of this thesis for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree of Master of Science, with a major in Food Science and Technology. Jennifer K. Richards, Major Professor We have read this thesis and recommend its acceptance: Faith Critzer, Phil Perkins Accepted for the Council: Carolyn R. Hodges Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School (Original signatures are on file with official studentecor r ds.) The Food Industry’s Perception of Economically Motivated Adulteration and Related Risk Factors A Thesis Presented for the Master of Science Degree The University of Tennessee, Knoxville Lindsay Colleen Murphy May 2016 ABSTRACT The United States of America has numerous safeguards in place to protect our food supply, including federal regulations and the food and beverage industry’s dedication to food safety. -

Global Lithium Sources—Industrial Use and Future in the Electric Vehicle Industry: a Review

resources Review Global Lithium Sources—Industrial Use and Future in the Electric Vehicle Industry: A Review Laurence Kavanagh * , Jerome Keohane, Guiomar Garcia Cabellos, Andrew Lloyd and John Cleary EnviroCORE, Department of Science and Health, Institute of Technology Carlow, Kilkenny, Road, Co., R93-V960 Carlow, Ireland; [email protected] (J.K.); [email protected] (G.G.C.); [email protected] (A.L.); [email protected] (J.C.) * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 28 July 2018; Accepted: 11 September 2018; Published: 17 September 2018 Abstract: Lithium is a key component in green energy storage technologies and is rapidly becoming a metal of crucial importance to the European Union. The different industrial uses of lithium are discussed in this review along with a compilation of the locations of the main geological sources of lithium. An emphasis is placed on lithium’s use in lithium ion batteries and their use in the electric vehicle industry. The electric vehicle market is driving new demand for lithium resources. The expected scale-up in this sector will put pressure on current lithium supplies. The European Union has a burgeoning demand for lithium and is the second largest consumer of lithium resources. Currently, only 1–2% of worldwide lithium is produced in the European Union (Portugal). There are several lithium mineralisations scattered across Europe, the majority of which are currently undergoing mining feasibility studies. The increasing cost of lithium is driving a new global mining boom and should see many of Europe’s mineralisation’s becoming economic. The information given in this paper is a source of contextual information that can be used to support the European Union’s drive towards a low carbon economy and to develop the field of research. -

Rulers of Opinion Women at the Royal Institution of Great Britain, 1799

Rulers of Opinion Women at the Royal Institution of Great Britain, 1799-1812 Harriet Olivia Lloyd UCL Submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History of Science 2018 1 I, Harriet Olivia Lloyd, confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated in the thesis. 2 Abstract This thesis examines the role of women at the Royal Institution of Great Britain in its first decade and contributes to the field by writing more women into the history of science. Using the method of prosopography, 844 women have been identified as subscribers to the Royal Institution from its founding on 7 March 1799, until 10 April 1812, the date of the last lecture given by the chemist Humphry Davy (1778- 1829). Evidence suggests that around half of Davy’s audience at the Royal Institution were women from the upper and middle classes. This female audience was gathered by the Royal Institution’s distinguished patronesses, who included Mary Mee, Viscountess Palmerston (1752-1805) and the chemist Elizabeth Anne, Lady Hippisley (1762/3-1843). A further original contribution of this thesis is to explain why women subscribed to the Royal Institution from the audience perspective. First, Linda Colley’s concept of the “service élite” is used to explain why an institution that aimed to apply science to the “common purposes of life” appealed to fashionable women like the distinguished patronesses. These women were “rulers of opinion,” women who could influence their peers and transform the image of a degenerate ruling class to that of an élite that served the nation. -

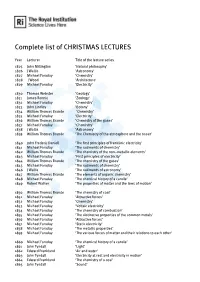

Complete List of CHRISTMAS LECTURES

Complete list of CHRISTMAS LECTURES Year Lecturer Title of the lecture series 1825 John Millington ‘Natural philosophy’ 1826 J Wallis ‘Astronomy’ 1827 Michael Faraday ‘Chemistry’ 1828 J Wood ‘Architecture’ 1829 Michael Faraday ‘Electricity’ 1830 Thomas Webster ‘Geology’ 1831 James Rennie ‘Zoology’ 1832 Michael Faraday ‘Chemistry’ 1833 John Lindley ‘Botany’ 1834 William Thomas Brande ‘Chemistry’ 1835 Michael Faraday ‘Electricity’ 1836 William Thomas Brande ‘Chemistry of the gases’ 1837 Michael Faraday ‘Chemistry’ 1838 J Wallis ‘Astronomy’ 1839 William Thomas Brande ‘The Chemistry of the atmosphere and the ocean’ 1840 John Frederic Daniell ‘The first principles of franklinic electricity’ 1841 Michael Faraday ‘The rudiments of chemistry’ 1842 William Thomas Brande ‘The chemistry of the non–metallic elements’ 1843 Michael Faraday ‘First principles of electricity’ 1844 William Thomas Brande ‘The chemistry of the gases’ 1845 Michael Faraday ‘The rudiments of chemistry’ 1846 J Wallis ‘The rudiments of astronomy’ 1847 William Thomas Brande ‘The elements of organic chemistry’ 1848 Michael Faraday ‘The chemical history of a candle’ 1849 Robert Walker ‘The properties of matter and the laws of motion’ 1850 William Thomas Brande ‘The chemistry of coal’ 1851 Michael Faraday ‘Attractive forces’ 1852 Michael Faraday ‘Chemistry’ 1853 Michael Faraday ‘Voltaic electricity’ 1854 Michael Faraday ‘The chemistry of combustion’ 1855 Michael Faraday ‘The distinctive properties of the common metals’ 1856 Michael Faraday ‘Attractive forces’ 1857 Michael Faraday -

the Papers Philosophical Transactions

ABSTRACTS / OF THE PAPERS PRINTED IN THE PHILOSOPHICAL TRANSACTIONS OF THE ROYAL SOCIETY OF LONDON, From 1800 to1830 inclusive. VOL. I. 1800 to 1814. PRINTED, BY ORDER OF THE PRESIDENT AND COUNCIL, From the Journal Book of the Society. LONDON: PRINTED BY RICHARD TAYLOR, RED LION COURT, FLEET STREET. CONTENTS. VOL. I 1800. The Croonian Lecture. On the Structure and Uses of the Meinbrana Tympani of the Ear. By Everard Home, Esq. F.R.S. ................page 1 On the Method of determining, from the real Probabilities of Life, the Values of Contingent Reversions in which three Lives are involved in the Survivorship. By William Morgan, Esq. F.R.S.................... 4 Abstract of a Register of the Barometer, Thermometer, and Rain, at Lyndon, in Rutland, for the year 1798. By Thomas Barker, Esq.... 5 n the Power of penetrating into Space by Telescopes; with a com parative Determination of the Extent of that Power in natural Vision, and in Telescopes of various Sizes and Constructions ; illustrated by select Observations. By William Herschel, LL.D. F.R.S......... 5 A second Appendix to the improved Solution of a Problem in physical Astronomy, inserted in the Philosophical Transactions for the Year 1798, containing some further Remarks, and improved Formulae for computing the Coefficients A and B ; by which the arithmetical Work is considerably shortened and facilitated. By the Rev. John Hellins, B.D. F.R.S. .......................................... .................................. 7 Account of a Peculiarity in the Distribution of the Arteries sent to the ‘ Limbs of slow-moving Animals; together with some other similar Facts. In a Letter from Mr. -

Alfred Swaine Taylor, Md, Frs (1806-1880): Forensic Toxicologist

Medical History, 1991, 35: 409-427. ALFRED SWAINE TAYLOR, MD, FRS (1806-1880): FORENSIC TOXICOLOGIST by NOEL G. COLEY * The systematic study of forensic toxicology dates from the end of the eighteenth century. It arose as a branch of forensic medicine concerned with the problem of proving deliberate poisoning in criminal cases. It was often very difficult to distinguish symptoms produced by many common poisonous plants like belladonna (deadly nightshade) and henbane from those of certain diseases. Medicines also frequently involved the use of poisonous substances and most physicians agreed that a better knowledge of the chemical properties and physiological effects of poisons would aid diagnosis and treatment as well as the search for antidotes. Moreover, some physiologists thought that the ability to trace the passage ofpoisons through the body would offer a new tool for investigating metabolic changes and the functions of the organs. All of these advances would depend on the development of more reliable methods of chemical analysis. The common reagents, such as barium chloride, silver nitrate, hydrogen sulphide or copper sulphate, used by chemists to identify mineral substances had long been known, but from the beginning ofthe nineteenth century the methods ofinorganic qualitative analysis were improved and systematized. 1 New tests were added to those already well-known, new techniques were devised and better analytical schemes for the identification of mineral acids, bases, and salts in solution were drawn up. Chemists like Richard Kirwan2 in Ireland studied the analysis of minerals and mineral waters while C. R. Fresenius, in Germany, who in 1862 founded the first journal entirely devoted to analytical chemistry,3 devised the first workable analytical tables. -

02. Chemistry Sets 1

II Three Centuries of the Chemistry Set Part I: The 18th and 19th Centuries 1. Introduction A few caveats before I begin (1). The history of the chemistry set is more of an exercise in the history of popular culture than in the history of science proper. One simply doesn’t go to the library and look up the relevant monographs and journal articles. Most of what I have discovered has been fortuitous and haphazard – the result of accidentally stumbling on an advertise- ment in an old magazine or in the back of an old text- book, or the result of happening on an old chemistry set at a garage sale or in a second-hand shop. Most of the companies that produced the chemistry sets we will be talking about no longer exist, and the same is equally true of the company’s records. As a result, I cannot guarantee that what follows is a complete his- tory. Important gaps may be present, but at least it is a beginning. Also, for obvious reasons, most of what I have to tell you will involve British and American chemistry sets, though there is doubtlessly an equally rich history for continental Europe and for Australia and New Zealand. Figure 1. A French version of Göttling’s Portable Chest of 2. 18th-Century Chemistry Sets Chemistry now in the Smithsonian. The earliest chemistry set I have been able to locate heard complaint that they don’t make chemistry sets dates back to the years 1789-1790 and was designed by like they used to, has a certain validity after all. -

Lithium 200 Years Fathi Habashi

Laval University From the SelectedWorks of Fathi Habashi September, 2017 Lithium 200 years Fathi Habashi Available at: https://works.bepress.com/fathi_habashi/242/ METALL-RUBMETALL-HISTORIKRISCH statesman. He was greatly honoured (Fig- Two Hundred Years Lithium ure 3). Discovery of Lithium Habashi, F. (1) When the French chemist Vauquelin ana- In 1800, Jozé Bonifacio de Andrade e Silva (1763-1838) a Brazilian scientist was lyzed spodumene in 1801 he showed a loss sent on a journey through Europe to study chemistry, mineralogy, and metallurgy. of 9.5% which he could not account for. In He was appointed as the first professor of metallurgy at the University of Coimbra 1817, the Swedish chemist Johan August in Portugal. Arfwedson (1792-1841) (Figure 4) while hile in Scandinavia he reported that he had discovered an infusible, laminated mineral from Wthe iron mine in Udö Island near Stock- holm which he called “petalite” (Figure 1) from Greek, leaf, alluding to its cleavage and another which he called “spodumene” (Figure 2) from a Greek word meaning ash colored. Fig. 4: Johan August Arfwedson (1792- 1841) working in Berzelius’ laboratory in Stock- holm analyzed petalite and spodumene and reported the presence of a new alkali Fig. 1: Petalite, LiAlSi4O10 or metal which he called “lithium” to indi- . Li2O Al2O3 8SiO2 cate that the metal was discovered in the mineral kingdom whereas the other alkali After returning to Brazil in 1819 he was metals were found in the vegetable king- appointed Minister of State and was dom. Both minerals are now known to instrumental in the independence of be lithium aluminum silicates. -

Weather Instruments All at Sea: Meteorology and the Royal Navy in the Nineteenth Century

n Naylor, S. (2015) Weather instruments all at sea: meteorology and the Royal Navy in the nineteenth century. In: MacDonald, F. and Withers, C. W.J. (eds.) Geography, Technology and Instruments of Exploration. Series: Studies in historical geography. Routledge: Farnham, pp. 77-96. ISBN 9781472434258. There may be differences between this version and the published version. You are advised to consult the publisher’s version if you wish to cite from it. http://eprints.gla.ac.uk/113110/ Deposited on: 26 February 2016 Enlighten – Research publications by members of the University of Glasgow http://eprints.gla.ac.uk Chapter 5 Weather instruments all at sea: Meteorology and the Royal Navy in the nineteenth century Simon Naylor Over the last two decades historians and geographers of science have paid increasing attention to science in the field. For one, ‘fieldwork has become the ideal type of knowledge’, so much so that much work in science studies asks not ‘about temporal priorities but about spatial coordination’.1 This agenda has been pursued empirically through study of European exploration in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. One of the key problematics for historians and geographers has been how, exactly, science collaborated with state actors to extend European nations’ ‘spatial grip’. There have been three common empirical responses to this question: through the deployment of physical observatories; through fieldwork; and by means of ships. Studies of observatories – on mountains, on the edge of oceans, in the polar regions – are many, as are studies of the ephemeral fieldsite.2 The ship has been seen to embody both of these types of scientific space.