Popular Astronomy Lectures in Nineteenth Century Britain

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mister Mary Somerville: Husband and Secretary

Open Research Online The Open University’s repository of research publications and other research outputs Mister Mary Somerville: Husband and Secretary Journal Item How to cite: Stenhouse, Brigitte (2020). Mister Mary Somerville: Husband and Secretary. The Mathematical Intelligencer (Early Access). For guidance on citations see FAQs. c 2020 The Author https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ Version: Version of Record Link(s) to article on publisher’s website: http://dx.doi.org/doi:10.1007/s00283-020-09998-6 Copyright and Moral Rights for the articles on this site are retained by the individual authors and/or other copyright owners. For more information on Open Research Online’s data policy on reuse of materials please consult the policies page. oro.open.ac.uk Mister Mary Somerville: Husband and Secretary BRIGITTE STENHOUSE ary Somerville’s life as a mathematician and mathematician). Although no scientific learned society had a savant in nineteenth-century Great Britain was formal statute barring women during Somerville’s lifetime, MM heavily influenced by her gender; as a woman, there was nonetheless a great reluctance even toallow women her access to the ideas and resources developed and into the buildings, never mind to endow them with the rights circulated in universities and scientific societies was highly of members. Except for the visit of the prolific author Margaret restricted. However, her engagement with learned institu- Cavendish in 1667, the Royal Society of London did not invite tions was by no means nonexistent, and although she was women into their hallowed halls until 1876, with the com- 90 before being elected a full member of any society mencement of their second conversazione [15, 163], which (Societa` Geografica Italiana, 1870), Somerville (Figure 1) women were permitted to attend.1 As late as 1886, on the nevertheless benefited from the resources and social nomination of Isis Pogson as a fellow, the Council of the Royal networks cultivated by such institutions from as early as Astronomical Society chose to interpret their constitution as 1812. -

Bull. Hist. Chem. 11

Bull. is. Cem. 11 ( 79 In consequence of this decision, many of the references in the index to volumes 1-20, 1816-26, of the Quarterly Journal of interleaved copy bear no correspondence to anything in the text Science and the Arts, published in 1826, in the possession of of the revised editions, the Royal Institution, has added in manuscript on its title-page Yet Faraday continued to add references between the dates "Made by M. Faraday", Since the cumulative index was of the second and third editions, that is, between 1830 and largely drawn from the separate indexes of each volume, it is 1842, One of these is in Section XIX, "Bending, Bowing and likely that the recurrent task of making those was also under- Cutting of Glass", which begins on page 522. It is listed as taken by Faraday. If such were indeed the case, he would have "Grinding of Glass" and refers to Silliman's Journal, XVII, had considerable experience in that kind of harmless drudgery, page 345, The reference is to a paper by Elisha Mitchell, dating from the days when his position at the Royal Institution Professor of Chemistry, Mineralogy, &c. at the University of was still that of an assistant to William Brande. Carolina, entitled "On a Substitute for WeIdler's Tube of Safety, with Notices of Other Subjects" (11). This paper is frn nd t interesting as it contains a reference to Chemical Manipulation and a practical suggestion on how to cut glass with a hot iron . M. aaay, Chl Mnpltn n Intrtn t (11): Stdnt n Chtr, n th Mthd f rfrn Exprnt f ntrtn r f rh, th Ar nd S, iis, M. -

Autobiography of Sir George Biddell Airy by George Biddell Airy 1

Autobiography of Sir George Biddell Airy by George Biddell Airy 1 CHAPTER I. CHAPTER II. CHAPTER III. CHAPTER IV. CHAPTER V. CHAPTER VI. CHAPTER VII. CHAPTER VIII. CHAPTER IX. CHAPTER X. CHAPTER I. CHAPTER II. CHAPTER III. CHAPTER IV. CHAPTER V. CHAPTER VI. CHAPTER VII. CHAPTER VIII. CHAPTER IX. CHAPTER X. Autobiography of Sir George Biddell Airy by George Biddell Airy The Project Gutenberg EBook of Autobiography of Sir George Biddell Airy by George Biddell Airy This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg Autobiography of Sir George Biddell Airy by George Biddell Airy 2 License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.net Title: Autobiography of Sir George Biddell Airy Author: George Biddell Airy Release Date: January 9, 2004 [EBook #10655] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK SIR GEORGE AIRY *** Produced by Joseph Myers and PG Distributed Proofreaders AUTOBIOGRAPHY OF SIR GEORGE BIDDELL AIRY, K.C.B., M.A., LL.D., D.C.L., F.R.S., F.R.A.S., HONORARY FELLOW OF TRINITY COLLEGE, CAMBRIDGE, ASTRONOMER ROYAL FROM 1836 TO 1881. EDITED BY WILFRID AIRY, B.A., M.Inst.C.E. 1896 PREFACE. The life of Airy was essentially that of a hard-working, business man, and differed from that of other hard-working people only in the quality and variety of his work. It was not an exciting life, but it was full of interest, and his work brought him into close relations with many scientific men, and with many men high in the State. -

Religion and Science in Abraham Ibn Ezra's Sefer Ha-Olam

RELIGION AND SCIENCE IN ABRAHAM IBN EZRA'S SEFER HA-OLAM (INCLUDING AN ENGLISH TRANSLATION OF THE HEBREW TEXT) Uskontotieteen pro gradu tutkielma Humanistinen tiedekunta Nadja Johansson 18.3.2009 1 CONTENTS 1 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................... 3 1.1 Abraham Ibn Ezra and Sefer ha-Olam ........................................................................ 3 1.2 Previous research ......................................................................................................... 5 1.3 The purpose of this study ............................................................................................. 8 2 SOURCE, METHOD AND THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK ....................................... 10 2.1 Primary source: Sefer ha-Olam (the Book of the World) ........................................... 10 2.1.1 Edition, manuscripts, versions and date .............................................................. 10 2.1.2 Textual context: the astrological encyclopedia .................................................... 12 2.1.3 Motivation: technical handbook .......................................................................... 14 2.2 Method ....................................................................................................................... 16 2.2.1 Translation and historical analysis ...................................................................... 16 2.2.2 Systematic analysis ............................................................................................. -

Mchenry County Illinois Genealogical Society 1011 N

McHenry County Illinois Genealogical Society 1011 N. Green St., McHenry, IL 60050 15 June 1988 Office of the Clerk of the Circuit Court McHenry County Court House Woodstock, IL 60098 Dear Ruth, Thank you for all the help you gave us in the preparation of this, our latest publication. Enclosed is a complimentary copy of the McHENRY COUNTY DECLARATIONS OF INTENT, SEPTEMBER 1851 - SEPTEMBER 1906, with our thanks. Sincerely, Jv.A,saaJ Publications Comm. M.C.I.G.S. McHENRY COUNTY ILLINOIS DECLARATIONS OF INTENT SEPTEMBER 1851—SEPTEMBER 1906 Published by McHenry County Illinois Genealogical Society loll North Green Street McHenry, Illinois 60050 1988 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the author. Copyright (D 1988 McHenry County Illinois Genealogical Society 10 11 North Green Street McHenry, Illinois 60050 Library of Congress Catalog Number: 88-61060 ISBN: 0-910741-08 PREFACE Early immigrants to the United States could apply for citizenship at any local court by filing a Declaration of Intent, often referred to as "First Papers". After a five-year residency the immigrant could submit his Citizenship Petition ("Final Papers") and become eligible for naturalization. The Declaration of Intent and the Citizenship Petition may not always be found in the same court. Often, after filing the Declaration, the applicant moved to another county or state and submitted his final petition there. Also, many immigrants made an initial Declaration of Intent in order to purchase land, but failed to have a final Citizenship Petition recorded by the court. -

The Maunder Minimum and the Variable Sun-Earth Connection

The Maunder Minimum and the Variable Sun-Earth Connection (Front illustration: the Sun without spots, July 27, 1954) By Willie Wei-Hock Soon and Steven H. Yaskell To Soon Gim-Chuan, Chua Chiew-See, Pham Than (Lien+Van’s mother) and Ulla and Anna In Memory of Miriam Fuchs (baba Gil’s mother)---W.H.S. In Memory of Andrew Hoff---S.H.Y. To interrupt His Yellow Plan The Sun does not allow Caprices of the Atmosphere – And even when the Snow Heaves Balls of Specks, like Vicious Boy Directly in His Eye – Does not so much as turn His Head Busy with Majesty – ‘Tis His to stimulate the Earth And magnetize the Sea - And bind Astronomy, in place, Yet Any passing by Would deem Ourselves – the busier As the Minutest Bee That rides – emits a Thunder – A Bomb – to justify Emily Dickinson (poem 224. c. 1862) Since people are by nature poorly equipped to register any but short-term changes, it is not surprising that we fail to notice slower changes in either climate or the sun. John A. Eddy, The New Solar Physics (1977-78) Foreword By E. N. Parker In this time of global warming we are impelled by both the anticipated dire consequences and by scientific curiosity to investigate the factors that drive the climate. Climate has fluctuated strongly and abruptly in the past, with ice ages and interglacial warming as the long term extremes. Historical research in the last decades has shown short term climatic transients to be a frequent occurrence, often imposing disastrous hardship on the afflicted human populations. -

A Newly-Discovered Accurate Early Drawing of M51, the Whirlpool Nebula

Journal of Astronomical History and Heritage , 11(2), 107-115 (2008). A NEWLY-DISCOVERED ACCURATE EARLY DRAWING OF M51, THE WHIRLPOOL NEBULA William Tobin 6 rue Saint Louis, 56000 Vannes, France. E-mail: [email protected] and J.B. Holberg Lunar and Planetary Laboratory, University of Arizona, 1541 East University Boulevard, Tucson, AZ 85721, U.S.A. E-mail: [email protected] Abstract: We have discovered a lost drawing of M51, the nebula in which spiral structure was first discovered by Lord Rosse. The drawing was made in April 1862 by Jean Chacornac at the Paris Observatory using Léon Foucault’s newly-completed 80-cm silvered-glass reflecting telescope. Comparison with modern images shows that Chacornac’s drawing was more accurate with respect to gross structure and showed fainter details than any other nineteenth century drawing, although its superiority would not have been apparent at the time without nebular photography to provide a standard against which to judge drawing quality. M51 is now known as the Whirlpool Nebula, but the astronomical appropriation of ‘whirlpool’ predates Rosse’s discovery. Keywords: reflecting telescopes, nebulae, spiral structure, Léon Foucault, Lord Rosse, M51, Whirlpool Nebula 1 REFLECTING TELESCOPES AND SPIRAL STRUCTURE The French physicist Léon Foucault (1819–1868) is the father of the reflecting telescope in its modern form, with large, optically-perfect, metallized glass or ceramic mirrors. Foucault achieved this breakthrough while working as ‘physicist’ at the Paris Observatory in the late 1850s. The largest telescope that he built (Foucault, 1862) had a silvered-glass, f/5.6 primary mirror of 80-cm diameter in a Newtonian configura- tion (see Figure 1). -

Goodman, Matthew (2018) from 'Magnetic Fever' to 'Magnetical Insanity': Historical Geographies of British Terrestrial Magnetic Research, 1833- 1857

Goodman, Matthew (2018) From 'magnetic fever' to 'magnetical insanity': historical geographies of British terrestrial magnetic research, 1833- 1857. PhD thesis. https://theses.gla.ac.uk/30829/ Copyright and moral rights for this work are retained by the author A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge This work cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Enlighten: Theses https://theses.gla.ac.uk/ [email protected] From ‘magnetic fever’ to ‘magnetical insanity’: historical geographies of British terrestrial magnetic research, 1833-1857 Matthew Goodman Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) School of Geographical and Earth Sciences College of Science and Engineering University of Glasgow Contents Abstract................................................................................................................................................................ 5 List of Figures .................................................................................................................................................... 6 Acknowledgements ......................................................................................................................................... -

Global Lithium Sources—Industrial Use and Future in the Electric Vehicle Industry: a Review

resources Review Global Lithium Sources—Industrial Use and Future in the Electric Vehicle Industry: A Review Laurence Kavanagh * , Jerome Keohane, Guiomar Garcia Cabellos, Andrew Lloyd and John Cleary EnviroCORE, Department of Science and Health, Institute of Technology Carlow, Kilkenny, Road, Co., R93-V960 Carlow, Ireland; [email protected] (J.K.); [email protected] (G.G.C.); [email protected] (A.L.); [email protected] (J.C.) * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 28 July 2018; Accepted: 11 September 2018; Published: 17 September 2018 Abstract: Lithium is a key component in green energy storage technologies and is rapidly becoming a metal of crucial importance to the European Union. The different industrial uses of lithium are discussed in this review along with a compilation of the locations of the main geological sources of lithium. An emphasis is placed on lithium’s use in lithium ion batteries and their use in the electric vehicle industry. The electric vehicle market is driving new demand for lithium resources. The expected scale-up in this sector will put pressure on current lithium supplies. The European Union has a burgeoning demand for lithium and is the second largest consumer of lithium resources. Currently, only 1–2% of worldwide lithium is produced in the European Union (Portugal). There are several lithium mineralisations scattered across Europe, the majority of which are currently undergoing mining feasibility studies. The increasing cost of lithium is driving a new global mining boom and should see many of Europe’s mineralisation’s becoming economic. The information given in this paper is a source of contextual information that can be used to support the European Union’s drive towards a low carbon economy and to develop the field of research. -

Rulers of Opinion Women at the Royal Institution of Great Britain, 1799

Rulers of Opinion Women at the Royal Institution of Great Britain, 1799-1812 Harriet Olivia Lloyd UCL Submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History of Science 2018 1 I, Harriet Olivia Lloyd, confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated in the thesis. 2 Abstract This thesis examines the role of women at the Royal Institution of Great Britain in its first decade and contributes to the field by writing more women into the history of science. Using the method of prosopography, 844 women have been identified as subscribers to the Royal Institution from its founding on 7 March 1799, until 10 April 1812, the date of the last lecture given by the chemist Humphry Davy (1778- 1829). Evidence suggests that around half of Davy’s audience at the Royal Institution were women from the upper and middle classes. This female audience was gathered by the Royal Institution’s distinguished patronesses, who included Mary Mee, Viscountess Palmerston (1752-1805) and the chemist Elizabeth Anne, Lady Hippisley (1762/3-1843). A further original contribution of this thesis is to explain why women subscribed to the Royal Institution from the audience perspective. First, Linda Colley’s concept of the “service élite” is used to explain why an institution that aimed to apply science to the “common purposes of life” appealed to fashionable women like the distinguished patronesses. These women were “rulers of opinion,” women who could influence their peers and transform the image of a degenerate ruling class to that of an élite that served the nation. -

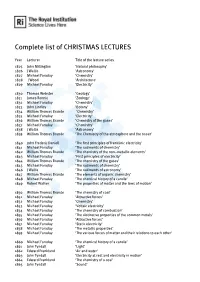

Complete List of CHRISTMAS LECTURES

Complete list of CHRISTMAS LECTURES Year Lecturer Title of the lecture series 1825 John Millington ‘Natural philosophy’ 1826 J Wallis ‘Astronomy’ 1827 Michael Faraday ‘Chemistry’ 1828 J Wood ‘Architecture’ 1829 Michael Faraday ‘Electricity’ 1830 Thomas Webster ‘Geology’ 1831 James Rennie ‘Zoology’ 1832 Michael Faraday ‘Chemistry’ 1833 John Lindley ‘Botany’ 1834 William Thomas Brande ‘Chemistry’ 1835 Michael Faraday ‘Electricity’ 1836 William Thomas Brande ‘Chemistry of the gases’ 1837 Michael Faraday ‘Chemistry’ 1838 J Wallis ‘Astronomy’ 1839 William Thomas Brande ‘The Chemistry of the atmosphere and the ocean’ 1840 John Frederic Daniell ‘The first principles of franklinic electricity’ 1841 Michael Faraday ‘The rudiments of chemistry’ 1842 William Thomas Brande ‘The chemistry of the non–metallic elements’ 1843 Michael Faraday ‘First principles of electricity’ 1844 William Thomas Brande ‘The chemistry of the gases’ 1845 Michael Faraday ‘The rudiments of chemistry’ 1846 J Wallis ‘The rudiments of astronomy’ 1847 William Thomas Brande ‘The elements of organic chemistry’ 1848 Michael Faraday ‘The chemical history of a candle’ 1849 Robert Walker ‘The properties of matter and the laws of motion’ 1850 William Thomas Brande ‘The chemistry of coal’ 1851 Michael Faraday ‘Attractive forces’ 1852 Michael Faraday ‘Chemistry’ 1853 Michael Faraday ‘Voltaic electricity’ 1854 Michael Faraday ‘The chemistry of combustion’ 1855 Michael Faraday ‘The distinctive properties of the common metals’ 1856 Michael Faraday ‘Attractive forces’ 1857 Michael Faraday -

the Papers Philosophical Transactions

ABSTRACTS / OF THE PAPERS PRINTED IN THE PHILOSOPHICAL TRANSACTIONS OF THE ROYAL SOCIETY OF LONDON, From 1800 to1830 inclusive. VOL. I. 1800 to 1814. PRINTED, BY ORDER OF THE PRESIDENT AND COUNCIL, From the Journal Book of the Society. LONDON: PRINTED BY RICHARD TAYLOR, RED LION COURT, FLEET STREET. CONTENTS. VOL. I 1800. The Croonian Lecture. On the Structure and Uses of the Meinbrana Tympani of the Ear. By Everard Home, Esq. F.R.S. ................page 1 On the Method of determining, from the real Probabilities of Life, the Values of Contingent Reversions in which three Lives are involved in the Survivorship. By William Morgan, Esq. F.R.S.................... 4 Abstract of a Register of the Barometer, Thermometer, and Rain, at Lyndon, in Rutland, for the year 1798. By Thomas Barker, Esq.... 5 n the Power of penetrating into Space by Telescopes; with a com parative Determination of the Extent of that Power in natural Vision, and in Telescopes of various Sizes and Constructions ; illustrated by select Observations. By William Herschel, LL.D. F.R.S......... 5 A second Appendix to the improved Solution of a Problem in physical Astronomy, inserted in the Philosophical Transactions for the Year 1798, containing some further Remarks, and improved Formulae for computing the Coefficients A and B ; by which the arithmetical Work is considerably shortened and facilitated. By the Rev. John Hellins, B.D. F.R.S. .......................................... .................................. 7 Account of a Peculiarity in the Distribution of the Arteries sent to the ‘ Limbs of slow-moving Animals; together with some other similar Facts. In a Letter from Mr.