Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bankettmappe Konferenz Und Events

Conferences & Events Conferences & Events Discover the “new center of Berlin” - located in the heart of Germany’s capital between “Potsdamer Platz” and “Alexanderplatz”. The Courtyard by Marriott Berlin City Center offers excellent services to its international clientele since the opening in June 2005. Just a short walk away, you find a few of Berlin’s main attractions, such as the famous “Friedrichstrasse” with the legendary Checkpoint Charlie, the “Gendarmenmarkt” and the “Nikolaiviertel”. Experience Berlin’s fascinating and exciting atmosphere and discover an extraordinary hotel concept full with comfort, elegance and a colorful design. Hotel information Room categories Hotel opening: June 2005 Total number: 267 Floors: 6 Deluxe: 118 Twin + 118 King / 26 sqm Non smoking rooms: 1st - 6th floor/ 267 rooms Superior: 21 rooms / 33 sqm (renovated in 2014) Junior Suite: 6 rooms / 44 sqm Conference rooms: 11 Suite: 4 rooms / 53 sqm (renovated in 2016) Handicap-accessible: 19 rooms Wheelchair-accessible: 5 rooms Check in: 03:00 p.m. Check out: 12:00 p.m. Courtyard® by Marriott Berlin City Center Axel-Springer-Strasse 55, 10117 Berlin T +49 30 8009280 | marriott.com/BERMT Room facilities King bed: 1.80 m x 2 m Twin bed: 1.20 m x 2 m All rooms are equipped with an air-conditioning, Pay-TV, ironing station, two telephones, hair dryer, mini-fridge, coffee and tea making facilities, high-speed internet access and safe in laptop size. Children Baby beds are free of charge and are made according to Marriott standards. Internet Wireless internet is available throughout the hotel and free of charge. -

Berlin - Wikipedia

Berlin - Wikipedia https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Berlin Coordinates: 52°30′26″N 13°8′45″E Berlin From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Berlin (/bɜːrˈlɪn, ˌbɜːr-/, German: [bɛɐ̯ˈliːn]) is the capital and the largest city of Germany as well as one of its 16 Berlin constituent states, Berlin-Brandenburg. With a State of Germany population of approximately 3.7 million,[4] Berlin is the most populous city proper in the European Union and the sixth most populous urban area in the European Union.[5] Located in northeastern Germany on the banks of the rivers Spree and Havel, it is the centre of the Berlin- Brandenburg Metropolitan Region, which has roughly 6 million residents from more than 180 nations[6][7][8][9], making it the sixth most populous urban area in the European Union.[5] Due to its location in the European Plain, Berlin is influenced by a temperate seasonal climate. Around one- third of the city's area is composed of forests, parks, gardens, rivers, canals and lakes.[10] First documented in the 13th century and situated at the crossing of two important historic trade routes,[11] Berlin became the capital of the Margraviate of Brandenburg (1417–1701), the Kingdom of Prussia (1701–1918), the German Empire (1871–1918), the Weimar Republic (1919–1933) and the Third Reich (1933–1945).[12] Berlin in the 1920s was the third largest municipality in the world.[13] After World War II and its subsequent occupation by the victorious countries, the city was divided; East Berlin was declared capital of East Germany, while West Berlin became a de facto West German exclave, surrounded by the Berlin Wall [14] (1961–1989) and East German territory. -

BERLIN SEMINAR June 9 to 18, 2021

BERLIN SEMINAR June 9 to 18, 2021 Designed with passionate scholars in mind, examine Prussian culture, Weimar-era decadence, World War II, the Cold War and reunification in Berlin during an up-close exploration of this storied European capital with history professor Jim Sheehan, ’58. FACULTY LEADER James Sheehan, ’58, is the Dickason Professor in the Humanities and professor emeritus of history at Stanford. His research focuses on 19th- and 20th-century European history, specifically on the relationship between ideas and social and economic conditions in modern Europe. His most recent book, Where Have All the Soldiers Gone?: The Transformation of Modern Europe, examines the decline of military institutions in Europe since 1945. He is now writing a book about the rise of European states in the modern era. About this program, Jim writes, “Berlin is one of the world’s great cities. In it, we encounter the past at every turn, in memorials and monuments, historic buildings and the ruined reminders of a troubled history. But contemporary Berlin is also full of life, music, art and excitement. Together we will explore Berlin’s past and present and the ways they interact and influence one another.” ● Dickason Professor in the Humanities, Stanford University ● Professor emeritus, department of history, Stanford University ● Senior fellow, by courtesy, Freeman Spogli Institute for International Studies, Stanford University ● Dean’s Award for Distinguished Teaching, Stanford University, 1993 ● Walter J. Gores Award for Excellence in Teaching, Stanford University, 1993 ● Guggenheim Fellow, 2000–2001 ● Fellow, American Academy of Arts and Sciences ● BA, 1958, Stanford University ● PhD, 1964, UC Berkeley ITINERARY Wednesday, June 9 Berlin, Germany Upon arrival in Berlin, transfer to our hotel, which is centrally located on the Gendarmenmarkt, an 18th- century town square that’s home to the Konzerthaus, the Huguenot Französischer Dom and the Deutscher Dom. -

Die Berliner Nikolaikirche Berlin's St. Nicholas Church Internationally

Berlin’s St. Nicholas Church Spurensuche Die frühe Berliner Stadtgeschichte Weltbekannt Kirchenlieder aus St. Nikolai Together with the Television Tower, the Red Town Hall and the St. Das Bodenniveau des mittelalterlichen Berlin lag über einen Meter Orgelbank und Sängerempore der Nikolaikirche waren nach der Mary’s Church the neo-gothic twin spires of the St. Nicholas Church tiefer als heute. In einer offenen archäologischen Sichtgrube Reformation eng mit dem Lehramt am Gymnasium zum Grauen characterise the skyline of today’s modern city centre. Once inside stehen Mauern des spätromanischen Vorgängerbaus frei. Kloster verbunden. Dies führte zu einem hohen Niveau der the oldest surviving Berlin building entering the fieldstone portal Der gesamte Grundriss dieses frühen Bauwerks ist auf dem musikalischen Praxis an St. Nikolai. Musikgeschichtlicher into the late Roman westwork, the view opens up through a wide Fußboden der heutigen Kirche nachgezeichnet. Höhepunkt war jedoch die besondere Zusammenarbeit zwischen gothic hall to the ambulatory that dates back to 1400. The church An einer interaktiven Medienstation können die Besucher der dem Nikolaipfarrer und Dichter Paul Gerhardt und dem Kantor is among the highlights of architecture in the Mark (Brandenburg) Geschichte erhaltener und verlorener mittelalterlicher Gebäude Johann Crüger sowie dessen Nachfolger Johann Georg Ebeling. and impressively reflects the self-confidence of a civil state nachspüren und im südlichen Turmjoch sogar bis auf die Sohle der Sowohl im Umfeld der Kanzel als auch auf der Orgelempore wird community. Even after the Reformation, Berlin’s citizens shaped Stadt hinabsteigen. Authentische Fundstücke vermitteln einen dieser berühmten Persönlichkeiten gedacht und ihr Werk mit their main parish church into a site of civic representation and a lebendigen Eindruck aus der Frühzeit der Doppelstadt Berlin-Cölln. -

Pdf/133 6.Pdf (Abgerufen Am 07.04.02)

ARBEITSBERICHTE Geographisches Institut, Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin M. Schulz (Hrsg.) Geographische Exkursionen in Berlin Teil 1 Heft 93 Berlin 2004 Arbeitsberichte Geographisches Institut Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin Heft 93 M. Schulz (Hrsg.) Geographische Exkursionen in Berlin Teil 1 Berlin 2004 ISSN 0947 - 0360 Geographisches Institut Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin Sitz: Rudower Chaussee 16 Unter den Linden 6 10099 Berlin (http://www.geographie.hu-berlin.de) Vorwort Der vorliegende Band ist im Rahmen eines Oberseminars zur Stadtentwicklung Berlins im Sommersemester 2002 entstanden. Die Leitidee der Lehrveranstaltung war die Kopplung von zwei wichtigen Arbeitsfeldern für Geographen - die Bearbeitung von stadtgeographischen Themen in ausgewählten Gebieten der Stadt und die Erarbeitung und Durchführung einer Exkursion zu diesem Thema. Jeder Teilnehmer konnte sich eine für ihn interessante Thematik auswählen und musste dann die Orte in Berlin suchen, in denen er das Thema im Rahmen einer zweistündigen Exkursion den anderen Teilnehmern des Oberseminars vorstellte. Das Ergebnis dieser Lehrveranstaltung liegt in Form eines Exkursionsführers vor. Die gewählten Exkursionsthemen spiegeln eine große Vielfalt wider. Sie wurden inhaltlich in drei Themenbereiche gegliedert: - Stadtsanierung im Wandel (drei Exkursionen) - Wandel eines Stadtgebietes als Spiegelbild politischer Umbrüche oder städtebaulicher Leitbilder (sieben Exkursionen) und - Bauliche Strukturen Berlins (drei Exkursionen). Die Exkursionen zeugen von dem großen Interesse aller beteiligten Studierenden an den selbst gewählten Themen. Alle haben mit großem Engagement die selbst erarbeitete Aufgabenstellung bearbeitet und viele neue Erkenntnisse gewonnen. Besonders hervorzuheben ist die Bereitschaft und Geduld von Herrn Patrick Klemm, den Texten der einzelnen Exkursionen ein einheitliches Layout zu geben, so dass die Ergebnisse nun in dieser ansprechenden Form vorliegen. Marlies Schulz Mai 2003 INHALTSVERZEICHNIS STADTSANIERUNG IM WANDEL 1. -

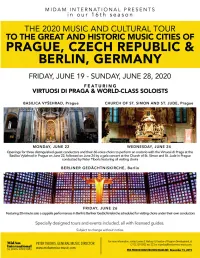

Published on February 11, 2019; Disregard All Previous Documents 1

Subject to change without notice; Published on February 11, 2019; disregard all previous documents 1 Subject to change without notice; Published on February 11, 2019; disregard all previous documents 2 Subject to change without notice; Published on February 11, 2019; disregard all previous documents 3 Subject to change without notice; Published on February 11, 2019; disregard all previous documents 4 2020 Music Tour to Prague and Berlin Registration Deadline: November 15, 2020 Two performances in The Basilica Vyšehrad and The Church of St. Simon and St. Jude On Monday, June 22 and Wednesday, June 24 Mozart’s Vesperae solennes de confessore, K. 339 Earl Rivers, conductor College-Conservatory of Music University of Cincinnati, Ohio And Director of Music Knox Presbyterian Church, Cincinnati, Ohio Virtuosi di Praga Oldřich Vlček, Artistic Director & World-class soloists PLUS Friday, June 26 An a cappella solo performance opportunity by visiting choirs In Berliner Gedächtniskirche A minimum of three groups must agree to perform for this concert to go forward. The Basilica Vyšehrad The Church of St. Simon and St. Jude Berliner Gedächtniskirche MidAm International, Inc. · 39 Broadway, Suite 3600 (36th FL) · New York, NY 10006 Tel. (212) 239-0205 · Fax (212) 563-5587 · www.midamerica-music.com Subject to change without notice; Published on February 11, 2019; disregard all previous documents 5 2020 MUSIC TOUR TO PRAGUE AND BERLIN: Itinerary Day 1 – Friday, June 19, 2020 – Arrive Prague • Arrive in Prague. MidAm International, Inc. staff and The Columbus Welcome Management staff will meet you at the airport and transfer you to Hotel Don Giovanni (http://www.hotelgiovanni.cz/en) for check-in. -

PDF-Dokument

mitten in berlin Standortmanagement 1. Fachkolloquium „Stadtverträglicher Tourismus und Teilraumentwicklungen“ Ergebnisprotokoll Ort: Karl-Liebknecht-Straße 11 Zeit: 04.04.2019, 16:30 - 20:00 Teilnehmende Verteiler Verfasser siehe Anhang Teilnahmeliste JMP, urbos standortmanagement@jahn- mack.de Telefon (0 30) 85 75 77 140 TOP 0: Begrüßung, Veranstaltungsablauf, Arbeitsplan des Standortmanagements TOP 1: Vorträge zu den Themen Tourismusentwicklung, Teilraum-, und Standortent- wicklungen und Erfahrungsberichte von Seiten der Akteure TOP 2: Gruppenarbeit zur Bildung von potenziellen Teilräumen im Gebiet „mitten in ber- lin“ TOP 3: Vorstellung der Ergebnisse TOP 4: Aktuelles, Termine Tagesordnungspunkte Zuständigkeit TOP 0: Begrüßung, Veranstaltungsablauf, Arbeitsplan des Standort- managements Frau Jahn begrüßt alle Anwesenden zum 1. Fachkolloquium aus der Ver- anstaltungsreihe mitten in berlin des Standortmanagements, mit dem The- ma „Stadtverträglicher Tourismus und Teilraumentwicklungen“. Frau Lassnig stellt den geplanten Ablauf der Veranstaltung, sowie den wei- teren Arbeitsplan des Standortmanagements vor (siehe Anlage II) Die Veranstaltung beginnt mit verschiedenen Vorträgen rund um die Themen Tourismus und Standortentwicklungen (siehe Anlage II) Im Anschluss geht es in die Diskussion/Arbeit in 3 Gruppen (blau, gelb, rot). Alle Gruppen orientieren sich an den gleichen Arbeits- schritten o Abgrenzung und Benennung der „Teilräume“ „mitten in ber- lin“ (z.B. Alexanderplatz, Nikolaiviertel) o Verträgliche Nutzungen/Mischungen – Bestand -

Factsheet Berlin

Capri by Fraser Berlin/Germany Scharrenstraße 22 10178 Berlin Germany T. +49 30 20 07 70 1888 BERLIN / GERMANY F. +49 30 20 07 70 1999 E: [email protected] Life, Styled High-tech and urban, Capri by Fraser Berlin / Germany gives guests the freedom to choose how and when they work, relax and play. A hotel residence catering to millennial business and leisure travellers, it is designed with round-the-clock lifestyles in mind. Historical touches reflect the history of its enviable location. A total of 143 hotel residences are available, ranging from Studios to One- bedroom Deluxe apartments. Facilities and services are designed to seamlessly combine work and play, day or night. Guests can brainstorm at the Pow-Wow business facility, workout at the 24/7 gym, or unwind and dine with friends or colleagues at Caprilicious. STUDIO CAPRILICIOUS GYM Category Size Hackescher Markt Bode-Museum Studio Deluxe 23 - 28 sqm Pergamonmuseum Studio Executive 29 - 30 sqm Neues Museum Deutsches Studio Premier 31 - 35 sqm Historisches Museum One Bedroom Deluxe 35 - 42 sqm Bebelplatz Nikolaiviertel Gendermenmarkt BERLIN / GERMANY Checkpoint Charlie Amenities • Complimentary high speed WiFi access * Not drawn to scale • 24/7 fully-equipped gym • Spin & Play (24/7 Laundrette) • Caprilicious (Restaurant) • Drinx (Bar) Capri by Fraser Berlin, Germany, has an enviable location in • HotSpot Station (Business Corner) the heart of the city. Situated in Mitte, near the Museum Island and Gendarmenmarkt, this brand new, hotel residen- ce is within walking distance of the popular museums in Meetings and Conferences Facilities Berlin's historic centre. The hotel residence is surrounded • Pow Wow 1&2 * by international organisations and close to excellent public * Charges apply transport links. -

Sehnsuchtsort Kurfürstendamm

Juni 2019 Nr. 06/19 2,00 € ART | CULTURE | SHOPPING | DINING | MORE 以中文 BERLINER 形式描述总 共四页的 推荐内容 DIE BIERGÄRTEN BERLINS UND IHR BESONDERER CHARME THE SPECIAL CHARM OF BERLIN´S BEER GARDENS DIE BESTEN TIPPS FÜR BARS UND RESTAURANTS TOP TIPS FOR BARS AND RESTAURANTS SEHNSUCHTSORT DREAM DESTINATION KURFÜRSTENDAMM 06 In Kooperation mit INKLUSIVE PLAN FÜR S- UND U-BAHN INCLUDING METRO PLAN 4 198235 302009 BERLIN: HAUPTSTADT DER SPIONE CAPITAL OF SPIES Erlebnis-Ausstellung über die Welt der Spionage A thrilling journey through the history of espionage Leipziger Platz 9, 10117 Berlin, Potsdamer Platz, Täglich 10 – 20 Uhr, www.deutsches-spionagemuseum.de INHALT | CONTENT INTRO Berlin entdecken Discover Berlin Geheime Orte erkunden: 6 Explore hidden gems: guided EDITORIAL Stadtführungen und walks and sightseeing tours will Stadtrundfahrten helfen dabei help you find your way around ls Joe Cocker so legendär sein „Summer in the City“ röhrte – da muss er einfach ABerlin vor Augen gehabt haben. Die Hauptstadt gilt nicht nur wegen der Sonne als eine der heißesten Metro- polen weltweit. Ein internationaler Hot DIE SCHÖNSTEN THE MOST BEAUTIFUL Spot, der gerade über die Sommer- BIERGÄRTEN BERLINS 10 BEER GARDENS IN BERLIN zeit pulsiert und sich keck heraus- © Benjamin Pritzkuleit putzt. Der Juni ist dafür besipielhaft: „Fête de la Musique“ mit hunderten Museen und Ausstellungen Museums and galleries Straßenkonzerten, das Kunstfestival Ausstellungsräume, Galerien 14 Exhibition spaces, galleries „48 Stunden Neukölln“ und das und Museen, die man unbedingt and museums – the must-see Bergmannstraßenfest. Staats- und besucht haben sollte locations around the city Komische Oper laden zu Open Air und Revue der Neuproduktionen. -

Pressemitteilung Humboldt Forum

Presseinformation Neuer Touristenmagnet: Humboldt Forum öffnet morgen digital Erste Einblicke mit virtuellen Rundgängen am 16. Dezember 2020 Etablierung von Berlins neuer kultureller Mitte Berlin, 15. Dezember 2020 Berlins Kulturlandschaft wird im historischen Zentrum der Hauptstadt um ein Highlight reicher: Am 16. Dezember 2020 findet die digitale Eröffnung des Berliner Humboldt Forums in Berlins neuer kultureller Mitte statt. Burkhard Kieker, Geschäftsführer von visitBerlin : „Mit dem Humboldt Forum bekommt Berlin ein neues markantes Wahrzeichen. Wenn Berlin-Reisen wieder möglich sind, wird sich das neue Haus als Magnet für Besucherinnen und Besucher etablieren. Bis dahin wecken die digitalen Einblicke schon einmal Vorfreude auf das neue Berlin-Highlight.“ In dem weltoffenen Forum für Kultur, Kunst und Wissenschaft werden auf 36.000 Quadratmetern mit abwechslungsreichen Formaten die Kernthemen Geschichte und Architektur des Ortes, die Brüder Humboldt sowie Kolonialismus dem Publikum zugänglich gemacht. Aufgrund der Corona-Restriktionen werden die Besucher das Humboldt Forum zunächst digital erleben. Angeboten werden am 16. Dezember ab 19 Uhr virtuelle Rundgänge durch das Gebäude, sowohl live gestreamt als auch online geführt. Eingebettet ist das Humboldt Forum in die geschichtliche Stadtlandschaft von Museumsinsel, Berliner Dom, Kronprinzenpalais und Nikolaiviertel. Die Architektur: eine kontrastreiche Verbindung hochmoderner Bauelemente mit den rekonstruierten Fassaden des ehemaligen Berliner Barockschlosses. Über sechs Portale zugänglich, -

Final Unformatted Bilbio Revised

Université de Montréal Urban planning and identity: the evolution of Berlin’s Nikolaiviertel par Mathieu Robinson Département de littératures et langues du monde, Faculté des arts et des sciences Mémoire présenté en vue de l’obtention du grade de Maîtrise ès arts en études allemandes Mars 2020 © Mathieu Robinson, 2020 RÉSUMÉ Le quartier du Nikolaiviertel, situé au centre de Berlin, est considéré comme le lieu de naissance de la ville remontant au 13e siècle. Malgré son charme médiéval, le quartier fut construit dans les années 1980. Ce dernier a été conçu comme moyen d’enraciner l’identité est-allemande dans le passé afin de se démarquer culturellement de ces voisins à l’ouest, et ce, à une époque de détente et de rapprochement entre la République démocratique allemande (RDA) et la République fédérale d’Allemagne (RFA). Depuis la construction du quartier, Berlin a connu une transformation exceptionnelle; elle est passée de ville scindée à la capitale d’un des pays les plus puissants au monde. La question se pose : quelle est l’importance de Nikolaiviertel, ce projet identitaire est-allemand, dans le Berlin réunifié d’aujourd’hui ? Ce projet part de l’hypothèse que le quartier est beaucoup plus important que laisse croire sa réputation de simple site touristique kitsch. En étudiant les rôles que joue le Nikolaiviertel dans la ville d’aujourd’hui, cette recherche démontre que le quartier est un important lieu identitaire au centre de la ville puisqu’il représente simultanément une multiplicité d’identités indissociables à Berlin, c’est-à-dire une identité locale berlinoise, une identité nationale est-allemande et une identité supranationale européenne. -

Berlin Kulinarisch

Berlin kulinarisch 15.192 gastronomische Betriebe in Berlin 9.455 Restaurants, Imbisse, Cafés & Eisdielen 1.903 Schankwirtschaften, Bars, Discos, Tanzlokale & Trinkhallen + 3.834 sonstige gastronomische Betriebe (Caterer, Verpflegungsdienstleister usw.) In Berlin gibt es 48 vegane & 193 vegetarische Restaurants & Cafés. In Berlin gibt es 1.600 Dönerläden Pro Jahr werden etwa 70 Mio. Täglich werden hier 400.000 Currywürste Döner in der Stadt gegessen! verkauft. 24 Foodtrucks sind täglich in Berlin unterwegs. In Berlin gibt es 65 Craft Beer- Betriebe. In Berlin gibt es 42 Kaffeeröstereien. Berlin hat 26 Michelin Sterne 6 × Restaurants 14 × Restaurants Restaurant-Empfehlungen rund um die touristischen Hotspots Friedrichstraße Reinhardtstraße 03 Spree Schiller Backstube 01 S+U Friedrichstraße U Mohrenstraße 02 Brasserie Desbrosses U Bundestag 08 Ishin Mittelstraße Spree Einstein unter den Linden 04 Leipziger Straße 07 Tiergartenstraße Ki-Nova 05 U Potsdamer Platz 09 Unter den Linden Lutter & Wegner Wilhelmstraße Brandenburger Tor 06 Facil Cookies Cream Stresemannstraße Straße des 17. Juni U Französische Straße Reichpietschufer Kochstraße Sra Bua by Tim Raue 10 Friedrichstraße Landwehrkanal Schöneberger Ufer Weingalerie und Café NÖ! U Hausvogteiplatz U Mendelssohn- S Anhalter Bahnhof Bartholdy-Park U Stadtmitte U Mohrenstraße Lennéstraße Leipziger Str. Potsdamer Straße Ebertstraße Leipziger Str. U Potsdamer Platz S Potsdamer Platz Wilhelmstraße U Kurfürstenstraße U Möckernbrücke Reichpietschufer Stresemannstraße Landwehrkanal U Kochstraße Schöneberger Ufer Axel-Springer-Straße Rudi-Dutschke-Str. Friedrichstraße S Anhalter Bahnhof B r Po tz ran To tsdamer Pla denburger Cecconi's 19 Hardenbergstraße U Rosenthaler Platz 20 Torstraße Torstraße 18 The Store Kitchen Mollstraße S+U Zoologischer Garten Shiori Kantstaße U Weinmeisterstraße What Do You Kaiser-Wilhelm- Gedächtnis-Kirche Fancy Love? 13 Tauentzienstraße Karl-Liebknecht-Str.