Presentation in Horace's Satires and Epodes. Phd Thesis. Ht

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Adultery and Roman Identity in Horace's Satires

Adultery and Roman Identity in Horace’s Satires Horace’s protestations against adultery in the Satires are usually interpreted as superficial, based not on the morality of the act but on the effort that must be exerted to commit adultery. For instance, in Satire I.2, scholars either argue that he is recommending whatever is easiest in a given situation (Lefèvre 1975), or that he is recommending a “golden mean” between the married Roman woman and the prostitute, which would be a freedwoman and/or a courtesan (Fraenkel 1957). It should be noted that in recent years, however, the latter interpretation has been dismissed as a “red herring” in the poem (Gowers 2012). The aim of this paper is threefold: to link the portrayals of adultery in I.2 and II.7, to show that they are based on a deeper reason than easy access to sex, and to discuss the political implications of this portrayal. Horace argues in Satire I.2 against adultery not only because it is difficult, but also because the pursuit of a married woman emasculates the Roman man, both metaphorically, and, in some cases, literally. Through this emasculation, the poet also calls into question the adulterer’s identity as a Roman. Satire II.7 develops this idea further, focusing especially on the adulterer’s Roman identity. Finally, an analysis of Epode 9 reveals the political uses and implications of the poet’s ideas of adultery and situates them within the larger political moment. Important to this argument is Ronald Syme’s claim that Augustus used his poets to subtly spread his ideology (Syme 1960). -

Iambic Metapoetics in Horace, Epodes 8 and 12 Erika Zimmerman Damer University of Richmond, [email protected]

University of Richmond UR Scholarship Repository Classical Studies Faculty Publications Classical Studies 2016 Iambic Metapoetics in Horace, Epodes 8 and 12 Erika Zimmerman Damer University of Richmond, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.richmond.edu/classicalstudies-faculty- publications Part of the Classical Literature and Philology Commons Recommended Citation Damer, Erika Zimmermann. "Iambic Metapoetics in Horace, Epodes 8 and 12." Helios 43, no. 1 (2016): 55-85. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Classical Studies at UR Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Classical Studies Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of UR Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Iambic Metapoetics in Horace, Epodes 8 and 12 ERIKA ZIMMERMANN DAMER When in Book 1 of his Epistles Horace reflects back upon the beginning of his career in lyric poetry, he celebrates his adaptation of Archilochean iambos to the Latin language. He further states that while he followed the meter and spirit of Archilochus, his own iambi did not follow the matter and attacking words that drove the daughters of Lycambes to commit suicide (Epist. 1.19.23–5, 31).1 The paired erotic invectives, Epodes 8 and 12, however, thematize the poet’s sexual impotence and his disgust dur- ing encounters with a repulsive sexual partner. The tone of these Epodes is unmistakably that of harsh invective, and the virulent targeting of the mulieres’ revolting bodies is precisely in line with an Archilochean poetics that uses sexually-explicit, graphic obscenities as well as animal compari- sons for the sake of a poetic attack. -

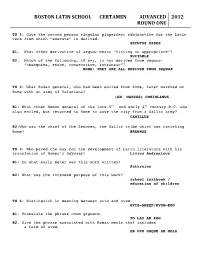

2012& ROUND&ONE&&! ! TU 1: Give the Second Person Singular Pluperfect Subjunctive for the Latin Verb from Which “Execute” Is Derived

BOSTON&LATIN&SCHOOL&&&&&&&CERTAMEN&&&&&&&&&&&ADVANCED&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&2012& ROUND&ONE&&! ! TU 1: Give the second person singular pluperfect subjunctive for the Latin verb from which “execute” is derived. SECUTUS ESSES B1. What other derivative of sequor means “fitting or appropriate”? SUITABLE B2. Which of the following, if any, is not derived from sequor: “obsequies, ensue, consecutive, intrinsic”? NONE: THEY ARE ALL DERIVED FROM SEQUOR TU 2: What Roman general, who had been exiled from Rome, later marched on Rome with an army of Volscians? (GN. MARCUS) CORIOLANUS B1: What other Roman general of the late 5th and early 4th century B.C. was also exiled, but returned to Rome to save the city from a Gallic army? CAMILLUS B2:Who was the chief of the Senones, the Gallic tribe which was ravishing Rome? BRENNUS TU 3: Who paved the way for the development of Latin literature with his translation of Homer’s Odyssey? Livius Andronicus B1: In what early meter was this work written? Saturnian B2: What was the intended purpose of this work? school textbook / education of children TU 4: Distinguish in meaning between ovis and ovum. OVIS—SHEEP/OVUM—EGG B1. Translate the phrase ovum gignere. TO LAY AN EGG B2. Give the phrase associated with Roman meals that includes a form of ovum. AB OVO USQUE AD MALA BOSTON&LATIN&SCHOOL&&&&&&&CERTAMEN&&&&&&&&&&&ADVANCED&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&&2012&& ROUND&ONE,&page&2&&&! TU 5: Who am I? The Romans referred to me as Catamitus. My father was given a pair of fine mares in exchange for me. According to tradition, it was my abduction that was one the foremost causes of Juno’s hatred of the Trojans? Ganymede B1: In what form did Zeus abduct Ganymede? eagle/whirlwind B2: Hera was angered because the Trojan prince replaced her daughter as cupbearer to the gods. -

Horace - Poems

Classic Poetry Series Horace - poems - Publication Date: 2012 Publisher: Poemhunter.com - The World's Poetry Archive Horace(8 December 65 BC – 27 November 8 BC) Quintus Horatius Flaccus, known in the English-speaking world as Horace, was the leading Roman lyric poet during the time of Augustus. The rhetorician Quintillian regarded his Odes as almost the only Latin lyrics worth reading, justifying his estimate with the words: "He can be lofty sometimes, yet he is also full of charm and grace, versatile in his figures, and felicitously daring in his choice of words." Horace also crafted elegant hexameter verses (Sermones and Epistles) and scurrilous iambic poetry (Epodes). The hexameters are playful and yet serious works, leading the ancient satirist Persius to comment: "as his friend laughs, Horace slyly puts his finger on his every fault; once let in, he plays about the heartstrings". Some of his iambic poetry, however, can seem wantonly repulsive to modern audiences. His career coincided with Rome's momentous change from Republic to Empire. An officer in the republican army that was crushed at the Battle of Philippi in 42 BC, he was befriended by Octavian's right-hand man in civil affairs, Maecenas, and became something of a spokesman for the new regime. For some commentators, his association with the regime was a delicate balance in which he maintained a strong measure of independence (he was "a master of the graceful sidestep") but for others he was, in < a href="http://www.poemhunter.com/john-henry-dryden/">John Dryden's</a> phrase, "a well-mannered court slave". -

Download Horace: the SATIRES, EPISTLES and ARS POETICA

+RUDFH 4XLQWXV+RUDWLXV)ODFFXV 7KH6DWLUHV(SLVWOHVDQG$UV3RHWLFD Translated by A. S. Kline ã2005 All Rights Reserved This work may be freely reproduced, stored, and transmitted, electronically or otherwise, for any non- commercial purpose. &RQWHQWV Satires: Book I Satire I - On Discontent............................11 BkISatI:1-22 Everyone is discontented with their lot .......11 BkISatI:23-60 All work to make themselves rich, but why? ..........................................................................................12 BkISatI:61-91 The miseries of the wealthy.......................13 BkISatI:92-121 Set a limit to your desire for riches..........14 Satires: Book I Satire II – On Extremism .........................16 BkISatII:1-22 When it comes to money men practise extremes............................................................................16 BkISatII:23-46 And in sexual matters some prefer adultery ..........................................................................................17 BkISatII:47-63 While others avoid wives like the plague.17 BkISatII:64-85 The sin’s the same, but wives are more trouble...............................................................................18 BkISatII:86-110 Wives present endless obstacles.............19 BkISatII:111-134 No married women for me!..................20 Satires: Book I Satire III – On Tolerance..........................22 BkISatIII:1-24 Tigellius the Singer’s faults......................22 BkISatIII:25-54 Where is our tolerance though? ..............23 BkISatIII:55-75 -

The Cord Weekly (September 29, 1999)

~ Wednesday, September 29, 1 999 • Volume 40, Issue 7 SiII%ox%)mrs Building up to peace the Cord /i, 16 3 News 8 Opinion 10 International 12 StudentLife 14 Features 16 Sports 22 Entertainment 26 Arts 27 Classifieds WLU's own Mr. Romance Yvonne Farah second game. Lifestlye section. The road to the contest all began Readers of the Sun then voted for when his mother in his their Sitting there in Student Union 24- fiancee's sent ten favourite ten men. to the ten to hour lounge with fiancee Natalie photo Toronto Sun newspaper. Those men then went on Gaudun, Harvey Stables looks like The Sun had announced a contest compete in the contest. football for the "hunkiest" heroes to out for So had to make the cut every other twenty something try Harvey player at WLU. the Mr. Romance '99 pageant. about four times before even starting little The received over 40() the Except for one thing, Harvey newspaper pageant. will entries from hundreds of kilometres The model he has just won one contest that cover competition in of the change his life. away. competed was part Romantic book On the weekendof September 17 to Times Magazine convention held in time 19 1999, Harvey competed in and Toronto, for the first this won the sixth Annual 1999 Mr. year. All it takes held the Romance Cover Model Pageant in The pageant was on Toronto. Saturday of the four-day convention. is mixture who a Ten Canadian and How does a guy grew up in competitors about a dozen from as far as Belleville, playing every sport from men, of luck the hockey to football and everything in- Germany, partook in competition end contest like this? at the Sheraton Centre. -

![The Poetic Element in the Satires and Epistles of Horace [Microform]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1834/the-poetic-element-in-the-satires-and-epistles-of-horace-microform-2071834.webp)

The Poetic Element in the Satires and Epistles of Horace [Microform]

MICROFILMED 1991 COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY LIBRARIES/NEW YORK as part of the "Foundations of Western Civilization Preservation Project Funded by the NATIONAL ENDOWMENT FOR THE HUMANITIES Reproductions may not be made without permission from Columbia University Library COPYRIGHT STATEMENT The copyright law of the United States ~ Title 17, United States Code - concerns the making of photocopies or other reproductions of copyrighted material... Columbia University Library reserves the right to refuse to accept a copy order if, in its judgement, fulfillment of the order would involve violation of the copyright law. : AUTHOR: EDWARDS, H. TITLE: ELEMENT IN THE SATIRES ...PART PLACE: BALT^MORE DA TE 1905 Master Negative # COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY LIBRARIES PRESERVATION DEPARTMENT BIBUOGRAPHIC MICROFORM TARGET Original Material as Filmed - Existing Bibliographic Record BKS/PROD Books FUL/BIB NYC691-B56418 Acquisitions NYCG-PT FIN ID IAUG88-B12783 ~ Record 1 of 1 - Record added today ID:NYCG91-B56418 RTYP:a ST:p FRN: MS: EL:1 AD 06-06-91 CC:9124 BLT:am DCF: CSC: MOO: SNR: ATC: UD 06-06-91 CP:nyu L:eng INT: GPC: BIO:d FIC:0 CON:b PC:r P0:1991/1905 REP: CPI:0 FSI:0 ILC: ME I :0 11:0 MMO: OR: POL: DM: RR: COL: EML: GEN BSE: 010 0637897 040 NNCt^cNNC 100 10 Edwards. Philip Howard, 1:dl878- 245 14 The poetic element in the Satires and Epistles of Horacet^h[ microform), ^npart I. 260 Baltimore,tt)J- H. Furst company , |:ci905. 300 47 p. , 1 KtC24 cm. 502 Thesis (PH. D.)--Johns Hopkins university. 500 Life. 504 Biblioqraphy : p. -

A STUDY of SOCIAL LIFE in the SATIRES of JUVENAL by BASHWAR NAGASSAR SURUJNATH B.A., the University of British Columbia, 1959. A

A STUDY OF SOCIAL LIFE IN THE SATIRES OF JUVENAL by BASHWAR NAGASSAR SURUJNATH B.A., The University of British Columbia, 1959. A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in the Department of CLASSICS We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA April, 1964 In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for reference and study. I further agree that per• mission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the Head of my Department or by his representatives. It is understood that copying or publi• cation of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission*. Department of Glassies The University of British Columbia, Vancouver 8, Canada Date April 28, 196U ii ABSTRACT The purpose of this thesis is not to deal with the literary merit and poetic technique of the satirist. I am not asking whether Juvenal was a good poet or not; instead, I intend to undertake this study strictly from a social and historical point of view. From our author's barrage of bitter protests on the follies and foibles of his age I shall try to uncover as much of the truth as possible (a) from what Juvenal himself says, (b) from what his contemporaries say of the same society, and (c) from the verdict of modern authorities. -

Summary of Horace's Satires

Horace Satires Summary of Horace’s Satires Book One 1 The need to find contentment with one’s lot, and the need to acquire the right habits of living in a state of carefree simplicity rather than being a lonely sad miser. 2 The need to practise safe sex: i.e. sex with women who are available and with whom one can have carefree relations. Adultery is a foolish game as (a) one cannot inspect the women before ‘buying’ and (b) it brings huge risks to health and reputation both in the fear of discovery and in being discovered and punished. Epicurean ethics of ‘the little that is enough’ means that whatever is available as a sexual outlet is preferable to pining with love for the unattainable. 3 The need to be indulgent to the faults of our friends if we want them to be indulgent towards us. The poet gives a quick version of Epicurean anthropology to explain the origins of morality and to discount the rigidity of Stoic ethics. 4 Horace’s first literary manifesto. He discusses Lucilius’ outspoken frankness and says that his poems are not really poetry at all but ‘closer to everyday speech.’ His choice of subject-matter is motivated not by malice but by a gentle desire to help others with the sort of good advice which his father had given him. 5 The journey to Brundisium. Horace went with Maecenas and other influential men (including Virgil) to conduct diplomatic discussions with Mark Antony in Spring 37BC. The poem avoids any overt political comment and focusses instead on the details of the journey and the accommodation ‘enjoyed’ or not. -

Illinois Classical Studies

— Quo, Quo Scelesti Ruitis: The Downward Momentum of Horace's Epodes' DAVID H. PORTER I. The Epodes' Structure of Descent It is clear that Horace has carefully arranged his collection of Epodes} Most obviously, there is the metrical sequence, with the first ten poems using an iambic couplet and the concluding seven ranging widely combinations of iambic and dactylic elements in 11 and 13-16, dactyls in 12, straight iambic trimeters in 17. There is also, as in Horace's other collections, the placement of Maecenas poems in positions of special importance. Epode 1, addressed to Maecenas as he sets off for Actium, begins the collection, and Epode 9, also to Maecenas, but this time celebrating the victory at Actium, is at the exact center. Moreover, these two "public" Maecenas poems (compare the more private 3 and 14) interlock with the two other Epodes that have a national theme, 7 and 16, both of which focus on the agony of the civil wars.^ From a different * I am pleased here to record my gratitude to ICS's two anonymous readers. Their comments and suggestions have led to significant improvements in this final version. ' Among many, see W. Port, "Die Anordnung in Gedichtbiichern augusteischer Zeit," Philologus 81 (1926) 291-96; R. W. Carrubba, The Epodes of Horace: A Study in Poetic Arrangement (The Hague 1969); K. Biichner, "Die Epoden des Horaz," in Werkanalysen. Studien zur romischen Literatur 8 (Wiesbaden 1970) 50-96; E. A. Schmidt, ""Arnica vis pastoribus: Der Jambiker Horaz in seinem Epodenbuch," Gymnasium 84 (1977) 401-23; H. Dettmer, Horace: A Study in Structure (Hildesheim 1983) 77-109; D. -

Bloomfield, the Poetry of Interpretation

The Poetry of Interpretation: Exegetical Lyric after the English Reformation Gabriel Bloomfield Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2019 © 2019 Gabriel Bloomfield All rights reserved ABSTRACT The Poetry of Interpretation: Exegetical Lyric after the English Reformation Gabriel Bloomfield “The Poetry of Interpretation” writes a pre-history of the twentieth-century phenomenon of close reading by interpreting the devotional poetry of the English Renaissance in the context of the period’s exegetical literatures. The chapters explore a range of hermeneutic methods that allowed preachers and commentators, writing in the wake of the Reformation’s turn to the “literal sense” of scripture, to grapple with and clarify the bible’s “darke texts.” I argue that early modern religious poets—principally Anne Lock, John Donne, George Herbert, William Alabaster, and John Milton—absorbed these same methods into their compositional practices, merging the arts of poesis and exegesis. Consistently skeptical about the very project they undertake, however, these poets became not just practitioners but theorists of interpretive method. Situated at the intersection of religious history, hermeneutics, and poetics, this study develops a new understanding of lyric’s formal operations while intimating an alternative history of the discipline of literary criticism. CONTENTS List of Illustrations ii Acknowledgments iii Note on Texts vi Introduction 1 1. Expolition: Anne Lock and the Poetics of Marginal Increase 33 2. Chopology: How the Poem Crumbles 87 3. Similitude: “Multiplied Visions” and the Experience of Homiletic Verse 147 4. Prosopopoeia: The Poem’s Split Personality 208 Bibliography 273 i LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS 1. -

The Six Books of Lucretius' De Rerum Natura: Antecedents and Influence

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Departmental Papers (Classical Studies) Classical Studies at Penn 2010 The Six Books of Lucretius’ De Rerum Natura: Antecedents and Influence Joseph Farrell University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/classics_papers Part of the Classics Commons Recommended Citation Farrell, J. (2010). The Six Books of Lucretius’ De Rerum Natura: Antecedents and Influence. Dictynna, 5 Retrieved from https://repository.upenn.edu/classics_papers/114 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/classics_papers/114 For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Six Books of Lucretius’ De Rerum Natura: Antecedents and Influence Abstract Lucretius’ De rerum natura is one of the relatively few corpora of Greek and Roman literature that is structured in six books. It is distinguished as well by features that encourage readers to understand it both as a sequence of two groups of three books (1+2+3, 4+5+6) and also as three successive pairs of books (1+2, 3+4, 5+6). This paper argues that the former organizations scheme derives from the structure of Ennius’ Annales and the latter from Callimachus’ book of Hynms. It further argues that this Lucretius’ union of these two six-element schemes influenced the structure employed by Ovid in the Fasti. An appendix endorses Zetzel’s idea that the six-book structure of Cicero’s De re publica marks that work as well as a response to Lucretius’ poem. Disciplines Arts and Humanities | Classics This journal article is available at ScholarlyCommons: https://repository.upenn.edu/classics_papers/114 The Six Books of Lucretius’ De rerum natura: Antecedents and Influence 2 Joseph Farrell The Six Books of Lucretius’ De rerum natura: Antecedents and Influence 1 The structure of Lucretius’ De rerum natura is generally considered one of the poem’s better- understood aspects.