From Pakistan and Iran

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pashtunistan: Pakistan's Shifting Strategy

AFGHANISTAN PAKISTAN PASHTUN ETHNIC GROUP PASHTUNISTAN: P AKISTAN ’ S S HIFTING S TRATEGY ? Knowledge Through Understanding Cultures TRIBAL ANALYSIS CENTER May 2012 Pashtunistan: Pakistan’s Shifting Strategy? P ASHTUNISTAN : P AKISTAN ’ S S HIFTING S TRATEGY ? Knowledge Through Understanding Cultures TRIBAL ANALYSIS CENTER About Tribal Analysis Center Tribal Analysis Center, 6610-M Mooretown Road, Box 159. Williamsburg, VA, 23188 Pashtunistan: Pakistan’s Shifting Strategy? Pashtunistan: Pakistan’s Shifting Strategy? The Pashtun tribes have yearned for a “tribal homeland” in a manner much like the Kurds in Iraq, Turkey, and Iran. And as in those coun- tries, the creation of a new national entity would have a destabilizing impact on the countries from which territory would be drawn. In the case of Pashtunistan, the previous Afghan governments have used this desire for a national homeland as a political instrument against Pakistan. Here again, a border drawn by colonial authorities – the Durand Line – divided the world’s largest tribe, the Pashtuns, into two the complexity of separate nation-states, Afghanistan and Pakistan, where they compete with other ethnic groups for primacy. Afghanistan’s governments have not recog- nized the incorporation of many Pashtun areas into Pakistan, particularly Waziristan, and only Pakistan originally stood to lose territory through the creation of the new entity, Pashtunistan. This is the foundation of Pakistan’s policies toward Afghanistan and the reason Pakistan’s politicians and PASHTUNISTAN military developed a strategy intended to split the Pashtuns into opposing groups and have maintained this approach to the Pashtunistan problem for decades. Pakistan’s Pashtuns may be attempting to maneuver the whole country in an entirely new direction and in the process gain primacy within the country’s most powerful constituency, the military. -

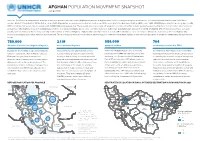

IRN Population Movement Snapshot June 2021

AFGHAN POPULATION MOVEMENT SNAPSHOT June 2021 Since the 1979 Soviet invasion and the subsequent waves of violence that have rocked Afghanistan, millions of Afghans have fled the country, seeking safety elsewhere. The Islamic Republic of Iran boasts 5,894 km of borders. Most of it, including the 921 km that are shared with Afghanistan, are porous and located in remote areas. While according to the Government of Iran (GIRI), some 1,400-2,500 Afghans arrive in Iran every day, recently GIRI has indicated increased daily movements with 4,000-5,000 arriving every day. These people aren’t necesserily all refugees, it is a mixed flow that includes people being pushed by the lack of economic opportunities as well as those who might be in need of international protection. The number fluctuates due to socio-economic challenges both in Iran and Afghanistan and also the COVID-19 situation. UNHCR Iran does not have access to border points and thus is unable to independently monitor arrivals or returns of Afghans. Afghans who currently reside in Iran have dierent statuses: some are refugees (Amayesh card holders), other are Afghans who posses a national passport, while other are undocumented. These populations move across borders in various ways. it is understood that many Afghans in Iran who have passports or are undocumented may have protection needs. 780,000 2.1 M 586,000 704 Amayesh Card Holders (Afghan refugees1) undocumented Afghans passport holders voluntarily repatriated in 2021 In 2001, the Government of Iran issues Amayesh Undocumented is an umbrella term used to There are 275,000 Afghans who hold family Covid-19 had a clear impact on the low VolRep cards to regularize the stay of Afghan refugees. -

Afghans in Iran: Migration Patterns and Aspirations No

TURUN YLIOPISTON MAANTIETEEN JA GEOLOGIAN LAITOKSEN JULKAISUJA PUBLICATIONS OF THE DEPARTMENT OF GEOGRAPHY AND GEOLOGY OF UNIVERSITY OF TURKU MAANTIETEEN JA GEOLOGIAN LAITOS DEPARTMENT OF GEOGRAPHY AND GEOLOGY Afghans in Iran: Migration Patterns and Aspirations Patterns Migration in Iran: Afghans No. 14 TURUN YLIOPISTON MAANTIETEEN JA GEOLOGIAN LAITOKSEN JULKAISUJA PUBLICATIONS FROM THE DEPARTMENT OF GEOGRAPHY AND GEOLOGY, UNIVERSITY OF TURKU No. 1. Jukka Käyhkö and Tim Horstkotte (Eds.): Reindeer husbandry under global change in the tundra region of Northern Fennoscandia. 2017. No. 2. Jukka Käyhkö och Tim Horstkotte (Red.): Den globala förändringens inverkan på rennäringen på norra Fennoskandiens tundra. 2017. No. 3. Jukka Käyhkö ja Tim Horstkotte (doaimm.): Boazodoallu globála rievdadusaid siste Davvi-Fennoskandia duottarguovlluin. 2017. AFGHANS IN IRAN: No. 4. Jukka Käyhkö ja Tim Horstkotte (Toim.): Globaalimuutoksen vaikutus porotalouteen Pohjois-Fennoskandian tundra-alueilla. 2017. MIGRATION PATTERNS No. 5. Jussi S. Jauhiainen (Toim.): Turvapaikka Suomesta? Vuoden 2015 turvapaikanhakijat ja turvapaikkaprosessit Suomessa. 2017. AND ASPIRATIONS No. 6. Jussi S. Jauhiainen: Asylum seekers in Lesvos, Greece, 2016-2017. 2017 No. 7. Jussi S. Jauhiainen: Asylum seekers and irregular migrants in Lampedusa, Italy, 2017. 2017 Nro 172 No. 8. Jussi S. Jauhiainen, Katri Gadd & Justus Jokela: Paperittomat Suomessa 2017. 2018. Salavati Sarcheshmeh & Bahram Eyvazlu Jussi S. Jauhiainen, Davood No. 9. Jussi S. Jauhiainen & Davood Eyvazlu: Urbanization, Refugees and Irregular Migrants in Iran, 2017. 2018. No. 10. Jussi S. Jauhiainen & Ekaterina Vorobeva: Migrants, Asylum Seekers and Refugees in Jordan, 2017. 2018. (Eds.) No. 11. Jussi S. Jauhiainen: Refugees and Migrants in Turkey, 2018. 2018. TURKU 2008 ΕήΟΎϬϣΕϼϳΎϤΗϭΎϫϮ̴ϟϥήϳέΩ̶ϧΎΘδϧΎϐϓϥήΟΎϬϣ ISBN No. -

REFUGEES Rn Lran* by Il Hobin Shorish University of Illinois At

Bismiallah THE AFGHAt! REFUGEES rn lRAN* by i.l. Hobin Shorish University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign Throughout the recent histories of Iran and Afghanistan refugees of one form or another have existed in each of these lands. Political and religious refugees have almost always constituted the majority of those who sought either Afghanistan or Iran as their new haven. The most recent Iranian wave of refugees in the Khurasan area of Afghanistan (Herat) has been those who feared the develop-· ment of conflict in Iran between the super powers during the Second World War. Since, fortunately, such a conflict did not develop some of the Iranians who fled to Herat and other western provinces of Afghanistan returned to Iran and others '"'ettled in these areas, especially in Herat, to become citizens of the Afghan kin~dom. In all fonns of human transmigration it is the magnitude of the people moving that create problems often for the host countries. Therefore:, an in vestigation into the problems of the Afghan refugees in Iran, and the Iranians' attidude toward these refugees was needed for the benefit of those concerned uith the tragedy of Afghanistan and the brutality befalling the Afghan people by the Russians and their puppets in Kabul. The Afghan Refugees--~heir Number and Origins: Today, in Iran the magnitude of the Afghan refugees is unknmm. The refugees themselves are vague in their ansuers to the questions eliciting the number. They often articulate their answer in the following manner: "There are manyn~ "There are a lot of them";: "Afghans are scattered from Tabriz to Tayabad"; ''We are everywhere". -

Pakistan's Future Policy Towards Afghanistan. a Look At

DIIS REPORT 2011:08 DIIS REPORT PAKISTAN’S FUTURE POLICY TOWARDS AFGHANISTAN A LOOK AT STRATEGIC DEPTH, MILITANT MOVEMENTS AND THE ROLE OF INDIA AND THE US Qandeel Siddique DIIS REPORT 2011:08 DIIS REPORT DIIS . DANISH INSTITUTE FOR INTERNATIONAL STUDIES 1 DIIS REPORT 2011:08 © Copenhagen 2011, Qandeel Siddique and DIIS Danish Institute for International Studies, DIIS Strandgade 56, DK-1401 Copenhagen, Denmark Ph: +45 32 69 87 87 Fax: +45 32 69 87 00 E-mail: [email protected] Web: www.diis.dk Cover photo: The Khyber Pass linking Pakistan and Afghanistan. © Luca Tettoni/Robert Harding World Imagery/Corbis Layout: Allan Lind Jørgensen Printed in Denmark by Vesterkopi AS ISBN 978-87-7605-455-7 Price: DKK 50.00 (VAT included) DIIS publications can be downloaded free of charge from www.diis.dk Hardcopies can be ordered at www.diis.dk This publication is part of DIIS’s Defence and Security Studies project which is funded by a grant from the Danish Ministry of Defence. Qandeel Siddique, MSc, Research Assistant, DIIS [email protected] 2 DIIS REPORT 2011:08 Contents Abstract 6 1. Introduction 7 2. Pakistan–Afghanistan relations 12 3. Strategic depth and the ISI 18 4. Shift of jihad theatre from Kashmir to Afghanistan 22 5. The role of India 41 6. The role of the United States 52 7. Conclusion 58 Defence and Security Studies at DIIS 70 3 DIIS REPORT 2011:08 Acronyms AJK Azad Jammu and Kashmir ANP Awani National Party FATA Federally Administered Tribal Areas FDI Foreign Direct Investment FI Fidayeen Islam GHQ General Headquarters GoP Government -

Analysis of Pakistan's Policy Towards Afghan Refugees

• p- ISSN: 2521-2982 • e-ISSN: 2707-4587 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.31703/gpr.2019(IV-III).04 • ISSN-L: 2521-2982 DOI: 10.31703/gpr.2019(IV-III).04 Muhammad Zubair* Muhammad Aqeel Khan† Muzamil Shah‡ Analysis of Pakistan’s Policy Towards Afghan Refugees: A Legal Perspective This article explores Pakistan’s policy towards Afghan refugees • Vol. IV, No. III (Summer 2019) Abstract since their arrival into Pakistan in 1979. As Pakistan has no • Pages: 28 – 38 refugee related law at national level nor is a signatory to the 1951 Refugee Convention or its Protocol of 1967; but despite of all these obstacles it has welcomed the refugees from Afghanistan after the Russian aggression. During their Headings stay here in Pakistan, these refugees have faced various problems due to the non- • Introduction existence of the relevant laws and have been treated under the Foreigner’s Act • Pakistan's Policy Towards Refugees of 1946, which did not apply to them. What impact this absence of law has made and Immigrants on the lives of these Afghan refugees? Here various phases of their arrival into • Overview of Afghan Refugees' Pakistan as well as the shift in policies of the government of Pakistan have been Situation in Pakistan also discussed in brief. This article explores all these obstacles along with possible • Conclusion legal remedies. • References Key Words: Influx, Refugees, Registration, SAFRON and UNHCR. Introduction Refugees are generally casualties of human rights violations. What's more, as a general rule, the massive portion of the present refugees are probably going to endure a two-fold violation: the underlying infringement in their state of inception, which will more often than not underlie their flight to another state; and the dissent of a full assurance of their crucial rights and opportunities in the accepting state. -

Afghanistan, Iran, and Pakistan

February 2002 Vol. 14, No. 2(G) AFGHANISTAN, IRAN, AND PAKISTAN CLOSED DOOR POLICY: Afghan Refugees in Pakistan and Iran “The bombing was so strong and we were so afraid to leave our homes. We were just like little birds in a cage, with all this noise and destruction going on all around us.” Testimony to Human Rights Watch I. MAP OF REFUGEE A ND IDP CAMPS DISCUSSED IN THE REPORT .................................................................................... 3 II. SUMMARY ............................................................................................................................................................................................... 4 III. INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................................................................................... 4 IV. CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS ............................................................................................................................ 6 To the Government of Iran:....................................................................................................................................................................... 6 To the Government of Pakistan:............................................................................................................................................................... 7 To UNHCR :............................................................................................................................................................................................... -

Education and Emigration: the Case of the Iranian-American Community

Education and Emigration: The case of the Iranian-American community Sina M. Mossayeb Teachers College, Columbia University Roozbeh Shirazi Teachers College, Columbia University Abstract This paper explores the plausibility of a hypothesis that puts forth perceived educational opportunity as a significant pull factor influencing Iranians' decisions to immigrate to the United States. Drawing on various literatures, including research on educational policy in Iran, government policy papers, and figures from recent studies and census data, the authors establish a case for investigating the correlation between perceived educational opportunity (or lack thereof) and immigration. Empirical findings presented here from a preliminary survey of 101 Iranian-born individuals living in the U.S. suggest that such a correlation may indeed exist, thus providing compelling grounds for further research in this area. The paper expands on existing literature by extending prevailing accounts of unfavorable conditions in Iran as push factors for emigration, to include the draw of perceived educational opportunity, as a coexisting and influential pull factor for immigration to the U.S. Introduction Popular discourse about Iranian immigration to the United States focuses on the social and political freedoms associated with relocation. The prevailing literature on Iranian immigration explains why people leave Iran, but accounts remain limited to a unilateral force--namely, unfavorable conditions in Iran. Drawing on existing studies of Iranian educational policies and their consequences, we propose an extension to this thesis. We hypothesize that perceived educational opportunity is a significant attraction for Iranians in considering immigration to the U.S. To establish a foundation for our research, we provide a background on Iran's sociopolitical climate after the 1978/1979 revolution and examine salient literature on Iran's higher education policy. -

PDF Fileiranian Migrations to Dubai: Constraints and Autonomy of A

Iranian Migrations to Dubai: Constraints and Autonomy of a Segmented Diaspora Amin Moghadam Working Paper No. 2021/3 January 2021 The Working Papers Series is produced jointly by the Ryerson Centre for Immigration and Settlement (RCIS) and the CERC in Migration and Integration www.ryerson.ca/rcis www.ryerson.ca/cerc-migration Working Paper No. 2021/3 Iranian Migrations to Dubai: Constraints and Autonomy of a Segmented Diaspora Amin Moghadam Ryerson University Series Editors: Anna Triandafyllidou and Usha George The Working Papers Series is produced jointly by the Ryerson Centre for Immigration and Settlement (RCIS) and the CERC in Migration and Integration at Ryerson University. Working Papers present scholarly research of all disciplines on issues related to immigration and settlement. The purpose is to stimulate discussion and collect feedback. The views expressed by the author(s) do not necessarily reflect those of the RCIS or the CERC. For further information, visit www.ryerson.ca/rcis and www.ryerson.ca/cerc-migration. ISSN: 1929-9915 Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 2.5 Canada License A. Moghadam Abstract In this paper I examine the way modalities of mobility and settlement contribute to the socio- economic stratification of the Iranian community in Dubai, while simultaneously reflecting its segmented nature, complex internal dynamics, and relationship to the environment in which it is formed. I will analyze Iranian migrants’ representations and their cultural initiatives to help elucidate the socio-economic hierarchies that result from differentiated access to distinct social spaces as well as the agency that migrants have over these hierarchies. In doing so, I examine how social categories constructed in the contexts of departure and arrival contribute to shaping migratory trajectories. -

Afghanistan: Political Exiles in Search of a State

Journal of Political Science Volume 18 Number 1 Article 11 November 1990 Afghanistan: Political Exiles In Search Of A State Barnett R. Rubin Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.coastal.edu/jops Part of the Political Science Commons Recommended Citation Rubin, Barnett R. (1990) "Afghanistan: Political Exiles In Search Of A State," Journal of Political Science: Vol. 18 : No. 1 , Article 11. Available at: https://digitalcommons.coastal.edu/jops/vol18/iss1/11 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Politics at CCU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Political Science by an authorized editor of CCU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ,t\fghanistan: Political Exiles in Search of a State Barnett R. Ru bin United States Institute of Peace When Afghan exiles in Pakistan convened a shura (coun cil) in Islamabad to choose an interim government on February 10. 1989. they were only the most recent of exiles who have aspired and often managed to Mrule" Afghanistan. The seven parties of the Islamic Union ofM ujahidin of Afghanistan who had convened the shura claimed that. because of their links to the mujahidin fighting inside Afghanistan. the cabinet they named was an Minterim government" rather than a Mgovernment-in exile. ~ but they soon confronted the typical problems of the latter: how to obtain foreign recognition, how to depose the sitting government they did not recognize, and how to replace the existing opposition mechanisms inside and outside the country. Exiles in Afghan History The importance of exiles in the history of Afghanistan derives largely from the difficulty of state formation in its sparsely settled and largely barren territory. -

Iran and the Soft Aw R Monroe Price University of Pennsylvania, [email protected]

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Departmental Papers (ASC) Annenberg School for Communication 2012 Iran and the Soft aW r Monroe Price University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/asc_papers Part of the Social Influence and Political Communication Commons Recommended Citation Price, M. (2012). Iran and the Soft aW r. International Journal of Communication, 6 2397-2415. Retrieved from https://repository.upenn.edu/asc_papers/732 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/asc_papers/732 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Iran and the Soft aW r Disciplines Communication | Social and Behavioral Sciences | Social Influence and Political Communication This journal article is available at ScholarlyCommons: https://repository.upenn.edu/asc_papers/732 International Journal of Communication 6 (2012), Feature 2397–2415 1932–8036/2012FEA0002 Iran and the Soft War MONROE PRICE University of Pennsylvania The events of the Arab Spring instilled in many authorities the considerable fear that they could too easily lose control over the narratives of legitimacy that undergird their power. 1 This threat to national power was already a part of central thinking in Iran. Their reaction to the Arab Spring was especially marked because of a long-held feeling that strategic communicators from outside the state’s borders were purposely reinforcing domestic discontent. I characterize strategic communications as, most dramatically, investment by an external source in methods to alter basic elements of a societal consensus. In this essay, I want to examine what this process looks like from what might be called the “inside,” the view from the perspective of the target society. -

Containing Iran: Strategies for Addressing the Iranian Nuclear Challenge Met Through Patient and Forward-Looking Policymaking

CHILDREN AND FAMILIES The RAND Corporation is a nonprofit institution that EDUCATION AND THE ARTS helps improve policy and decisionmaking through ENERGY AND ENVIRONMENT research and analysis. HEALTH AND HEALTH CARE This electronic document was made available from INFRASTRUCTURE AND www.rand.org as a public service of the RAND TRANSPORTATION Corporation. INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS LAW AND BUSINESS NATIONAL SECURITY Skip all front matter: Jump to Page 16 POPULATION AND AGING PUBLIC SAFETY SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY Support RAND Purchase this document TERRORISM AND HOMELAND SECURITY Browse Reports & Bookstore Make a charitable contribution For More Information Visit RAND at www.rand.org Explore the RAND Corporation View document details Limited Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law as indicated in a notice appearing later in this work. This electronic representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for non-commercial use only. Unauthorized posting of RAND electronic documents to a non-RAND website is prohibited. RAND electronic documents are protected under copyright law. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of our research documents for commercial use. For information on reprint and linking permissions, please see RAND Permissions. This product is part of the RAND Corporation monograph series. RAND monographs present major research findings that address the challenges facing the public and private sectors. All RAND mono- graphs undergo rigorous peer review to ensure high standards for research quality and objectivity. Containing Iran Strategies for Addressing the Iranian Nuclear Challenge Robert J. Reardon Supported by the Stanton Foundation C O R P O R A T I O N The research described in this report was supported by the Stanton Foundation.