Government of Belize

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PROPERTIES Cayo, Stann Creek & Toledo Districts: BY

PUBLIC AUCTION SALES: PROPERTIES Cayo, Stann Creek & Toledo Districts: BY ORDER of the Mortgagees, Messrs. The Belize Bank Limited, Licensed Auctioneer Kevin A. Castillo will sell the following properties on the dates, locations and times below listed: A. - Caye Caulker, Belize District: Lot situate 1.2 km north of the Split 1. In front Police Station, Hicaco Avenue, Caye Caulker, Belize District on Monday 6th November 2017 at 10:30 am: REGISTRATION SECTION BLOCK PARCEL Caye Caulker 12 1178 (Being a vacant parcel of land [49.99 feet X 99.97 feet = 555.28 square yards] situated approximately 1.2 kilometers north of "The Split" within walking distance of the beach, Caye Caulker Village, Belize District, the freehold property of Mr. Karim Adle) B - CAYO DISTRICT: Camalote Village (Highway Frontage), Belmopan, Cayo District; 2. At Parcel No. 3248 George Price Highway, Camalote Village, Cayo District on Tuesday 7th November 2017 at 9:00 am: REGISTRATION SECTION BLOCK PARCEL Society Hall 24 3248 (Being a vacant highway frontage lot [535.163 square meters (640.05 square yards)] situate beside the George Price Highway in the Village of Camalote, Cayo District, the freehold property of Mr. Armando Coleman) 3. At The Belize Bank Limited Parking Lot, Constitution Drive, Belmopan Cayo District on Tuesday 7th November 2017 at 9:45 am: REGISTRATION SECTION BLOCK PARCEL Belmopan 20 1524 (Being a vacant parcel of land comprising 6,818.879 square yards of land situated in Belmopan, Cayo District, the freehold property of Mr. Karim Adle) B - STANN CREEK & TOLEDO DISTRICTS: Carib Reserve, Tobacco Caye, Red Bank Village, Independence Village, Stann Creek District: Big Falls Area, Toledo District 4. -

Long-Term Development in Post-Disaster Intentional Communities in Honduras

From Tragedy to Opportunity: Long-term Development in Post-Disaster Intentional Communities in Honduras A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA BY Ryan Chelese Alaniz IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Ronald Aminzade June 2012 © Ryan Alaniz 2012 Acknowledgements Like all manuscripts of this length it took the patience, love, and encouragement of dozens of people and organizations. I would like to thank my parents for their support, numerous friends who provided feedback in informal conversations, my amazing editor and partner Jenny, my survey team, and the residents of Nueva Esperanza, La Joya, San Miguel Arcangel, Villa El Porvenir, La Roca, and especially Ciudad España and Divina for their openness in sharing their lives and experiences. Finally, I would like to thank Doug Hartmann, Pat McNamara, David Pellow, and Ross MacMillan for their generosity of time and wisdom. Most importantly I would like to express my gratitude to my advisor, Ron, who is an inspiration personally and professionally. I would also like to thank the following organizations and fellowship sponsors for their financial support: the University of Minnesota and the Department of Sociology, the Social Science Research Council, Fulbright, the Bilinski Foundation, the Public Entity Risk Institute, and the Diversity of Views and Experiences (DOVE) Fellowship. i Dedication This dissertation is dedicated to all those who have been displaced by a disaster and have struggled/continue to struggle to rebuild their lives. It is also dedicated to my son, Santiago. May you grow up with a desire to serve the most vulnerable. -

Tropical Cyclone Effects on California

/ i' NOAA Technical Memorandum NWS WR-~ 1s-? TROPICAL CYCLONE EFFECTS ON CALIFORNIA Salt Lake City, Utah October 1980 u.s. DEPARTMENT OF I National Oceanic and National Weather COMMERCE Atmospheric Administration I Service NOAA TECHNICAL ME~RANOA National Weather Service, Western R@(Jfon Suhseries The National Weather Service (NWS~ Western Rl!qion (WR) Sub5eries provide! an informal medium for the documentation and nUlck disseminuion of l"'eSUlts not appr-opriate. or nnt yet readY. for formal publication. The series is used to report an work in pronf"'!ss. to rie-tJ:cribe tl!1:hnical procedures and oractice'S, or to relate proqre5 s to a Hmitfd audience. The~J:e Technical ~ranc1i!l will report on investiqations rit'vot~ or'imaroi ly to rl!nionaJ and local orablems of interest mainly to personnel, "'"d • f,. nence wUl not hi! 'l!lidely distributed. Pacer<; I to Z5 are in the fanner series, ESSA Technical Hetooranda, Western Reqion Technical ~-··•nda (WRTMI· naoors 24 tn 59 are i·n the fanner series, ESSA Technical ~-rando, W.othel" Bureou Technical ~-randa (WSTMI. aeqinniM with "n. the oaoers are oa"t of the series. ltOAA Technical >4emoranda NWS. Out·of·print .....,rond1 are not listed. PanfiM ( tn 22, except for 5 {revised erlitinn), ar'l! availabll! froM tt'lt Nationm1 Weattuu• Service Wesurn Ret1inn. )cientific ~•,.,irr• Division, P.O. Box lllAA, Federal RuildiM, 125 South State Street, Salt La~• City, Utah R4147. Pacer 5 (revised •rlitinnl. and all nthei"S beqinninq ~ith 25 are available from the National rechnical Information Sel'"lice. II.S. -

The Geography of Fishing in British Honduras and Adjacent Coastal Areas

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1966 The Geography of Fishing in British Honduras and Adjacent Coastal Areas. Alan Knowlton Craig Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Craig, Alan Knowlton, "The Geography of Fishing in British Honduras and Adjacent Coastal Areas." (1966). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 1117. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/1117 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This dissertation has been „ . „ i i>i j ■ m 66—6437 microfilmed exactly as received CRAIG, Alan Knowlton, 1930— THE GEOGRAPHY OF FISHING IN BRITISH HONDURAS AND ADJACENT COASTAL AREAS. Louisiana State University, Ph.D., 1966 G eo g rap h y University Microfilms, Inc., Ann Arbor, Michigan THE GEOGRAPHY OP FISHING IN BRITISH HONDURAS AND ADJACENT COASTAL AREAS A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State university and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of Geography and Anthropology by Alan Knowlton Craig B.S., Louisiana State university, 1958 January, 1966 PLEASE NOTE* Map pages and Plate pages are not original copy. They tend to "curl". Filmed in the best way possible. University Microfilms, Inc. AC KNQWLEDGMENTS The extent to which the objectives of this study have been acomplished is due in large part to the faithful work of Tiburcio Badillo, fisherman and carpenter of Cay Caulker Village, British Honduras. -

Social Reorganization and Household Adaptation in the Aftermath of Collapse at Baking Pot, Belize

SOCIAL REORGANIZATION AND HOUSEHOLD ADAPTATION IN THE AFTERMATH OF COLLAPSE AT BAKING POT, BELIZE by Julie A. Hoggarth B.A. in Anthropology (Archaeology), University of California, San Diego, 2004 B.A. in Latin American Studies, University of California, San Diego, 2004 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Kenneth P. Dietrich School of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2012 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH KENNETH P. DIETRICH SCHOOL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES This dissertation was presented by Julie A. Hoggarth It was defended on November 14, 2012 and approved by: Dr. Olivier de Montmollin (Chair), Associate Professor, Anthropology Department Dr. Marc P. Bermann, Associate Professor, Anthropology Department Dr. Robert D. Drennan, Distinguished Professor, Anthropology Department Dr. Lara Putnam, Associate Professor, History Department ii Copyright © by Julie A. Hoggarth 2012 iii SOCIAL REORGANIZATION AND HOUSEHOLD ADAPTATION IN THE AFTERMATH OF COLLAPSE AT BAKING POT, BELIZE Julie A. Hoggarth, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2012 This dissertation focuses on the adaptations of ancient Maya households to the processes of social reorganization in the aftermath of collapse of Classic Maya rulership at Baking Pot, a small kingdom in the upper Belize River Valley of western Belize. With the depopulation of the central and southern Maya lowlands at the end of the Late Classic period, residents in Settlement Cluster C at Baking Pot persisted following the abandonment of the palace complex in the Terminal Classic period (A.D. 800-900). Results from this study indicate that noble and commoner households in Settlement Cluster C continued to live at Baking Pot, developing strategies of adaptation including expanding interregional mercantile exchange and hosting community feasts in the Terminal Classic and Early Postclassic periods. -

Biosecurity Amendment (Schedules to Act) Regulation 2017 Under the Biosecurity Act 2015

New South Wales Biosecurity Amendment (Schedules to Act) Regulation 2017 under the Biosecurity Act 2015 His Excellency the Governor, with the advice of the Executive Council, has made the following Regulation under the Biosecurity Act 2015. NIALL BLAIR, MLC Minister for Primary Industries Explanatory note The objects of this Regulation are: (a) to update the lists of pests and diseases of plants, pests and diseases of animals, diseases of aquatic animals, pest marine and freshwater finfish and pest marine invertebrates (set out in Part 1 of Schedule 2 to the Biosecurity Act 2015 (the Act)) that are prohibited matter throughout the State, and (b) to update the description (set out in Part 2 of Schedule 2 to the Act) of the part of the State in which Daktulosphaira vitifoliae (Grapevine phylloxera) is a prohibited matter, and (c) to include (in Schedule 3 to the Act) lists of non-indigenous amphibians, birds, mammals and reptiles in respect of which dealings are prohibited or permitted, and (d) to provide (in Schedule 4 to the Act) that certain dealings with bees and certain non-indigenous animals require biosecurity registration, and (e) to update savings and transitional provisions with respect to existing licences (in Schedule 7 to the Act). This Regulation is made under the Biosecurity Act 2015, including sections 27 (4), 151 (2), 153 (2) and 404 (the general regulation-making power) and clause 1 (1) and (5) of Schedule 7. Published LW 2 June 2017 (2017 No 230) Biosecurity Amendment (Schedules to Act) Regulation 2017 [NSW] Biosecurity Amendment (Schedules to Act) Regulation 2017 under the Biosecurity Act 2015 1 Name of Regulation This Regulation is the Biosecurity Amendment (Schedules to Act) Regulation 2017. -

Public Sector Investment Programme Report

GOVERNMENT OF BELIZE PUBLIC SECTOR INVESTMENT PROGRAMME REPORT Quarter ended June 30, 2019 Ministry of Economic Development, Petroleum, Investment, Trade and Commerce April 1, 2020 SUMMARY OF ONGOING PROJECTS PUBLIC SECTOR INVESTMENT PROGRAMME 2019/2020 QUARTER ENDED JUNE 30, 2019 FUNDING EXECUTING COST PROJECT DESCRIPTION L/G AGENCY AGENCY (BZD) INFRASTRUCTURE ROADS, STREETS, DRAINS & BRIDGES 1 San Ignacio/ Santa Elena Bypass (Macal Bridge) Project Construction of a bypass road and new all-weather bridge across the Macal River to increase the efficiency of road transportation in and through San Ignacio and CDB MOW L 49,438,000 Santa Elena. The project also includes activities to determine the extent of vehicle overloading and the accompanying economic and financial impacts. Additional works were identified along the George Price Highway to make use of surplus funds in the project. These are packaged as Lot 5 which includes the rehabilitation of GOB C 8,917,000 1,870 m of the G. Price Highway (Loma Luz Intersection to the Hawkesworth Bridge); 160 m along Liberty Street (GPH intersection - GP Avenue intersection); and 1,940 m of the George Price Avenue (Loma Luz Blvd - Hawkesworth Bridge). TOTAL $58,355,000 2 Fifth Road (Phillip S.W. Goldson Highway Upgrading) Project Upgrade of the Phillip Goldson Highway between the Airport Junction and the Chetumal Street Roundabout (including the Haulover Bridge). CDB MOW L 59,438,000 CDB G 222,000 CDF G 4,545,980 GOB C 19,000,000 OFID L 24,000,000 TOTAL $107,205,980 3 Belize City Southside Poverty Alleviation (Phase 2) Infrastructural, social and economic improvements in Southside Belize City. -

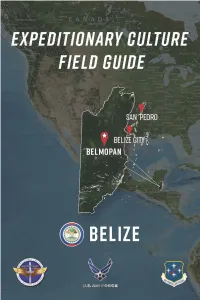

ECFG-Belize-2020R.Pdf

ECFG: Central America Central ECFG: About this Guide This guide is designed to prepare you to deploy to culturally complex environments and achieve mission objectives. The fundamental information contained within will help you understand the cultural dimension of your assigned location and gain skills necessary for success (Photo: US Marine shows members of Belize Defense Force how to load ammunition into weapons). The guide consists of 2 E parts: CFG Part 1 “Culture General” provides the foundational knowledge you need to operate effectively in any global environment with a focus on Central America (CENTAM). Part 2 “Culture Specific” describes unique cultural features of Belize Belizean society. It applies culture-general concepts to help increase your knowledge of your assigned deployment location. This section is designed to complement other pre- deployment training (Photo: USAF medic checks a Belizean patient’s vision during a medical readiness event). For further information, visit the Air Force Culture and Language Center (AFCLC) website at www.airuniversity.af.edu/AFCLC/ or contact the AFCLC Region Team at [email protected]. Disclaimer: All text is the property of the AFCLC and may not be modified by a change in title, content, or labeling. It may be reproduced in its current format with the express permission of the AFCLC. All photography is provided as a courtesy of the US government, Wikimedia, and other sources. GENERAL CULTURE PART 1 – CULTURE GENERAL What is Culture? Fundamental to all aspects of human existence, culture shapes the way humans view life and functions as a tool we use to adapt to our social and physical environments. -

Hurricanes and the Forests of Belize, Jon Friesner, 1993. Pdf 218Kb

Hurricanes and the Forests Of Belize Forest Department April 1993 Jon Friesner 1.0 Introduction Belize is situated within the hurricane belt of the tropics. It is periodically subject to hurricanes and tropical storms, particularly during the period June to July (figure 1). This report is presented in three sections. - A list of hurricanes known to have struck Belize. Several lists documenting cyclones passing across Belize have been produced. These have been supplemented where possible from archive material, concentrating on the location and degree of damage as it relates to forestry. - A map of hurricane paths across Belize. This has been produced on the GIS mapping system from data supplied by the National Climatic Data Centre, North Carolina, USA. Some additional sketch maps of hurricane paths were available from archive material. - A general discussion of matters relating to a hurricane prone forest resource. In order to most easily quote sources, and so as not to interfere with the flow of text, references are given as a number in brackets and expanded upon in the reference section. Summary of Hurricanes in Belize This report lists a total of 32 hurricanes. 1.1 On Hurricanes and Cyclones (from C.J.Neumann et al) Any closed circulation, in which the winds rotate anticlockwise in the Northern Hemisphere or clockwise in the Southern Hemisphere, is called a cyclone. Tropical cyclones refer to those circulations which develop over tropical waters, the tropical cyclone basins. The Caribbean Sea is included in the Atlantic tropical cyclone basin, one of six such basins. The others in the Northern Hemisphere are the western North Pacific (where such storms are called Typhoons), the eastern North Pacific and the northern Indian Ocean. -

LIST of REMITTANCE SERVICE PROVIDERS Belize Chamber Of

LIST OF REMITTANCE SERVICE PROVIDERS Name of Remittance Service Providers Addresses Belize Chamber of Commerce and Industry Belize Chamber of Commerce and Industry 4792 Coney Drive, Belize City Agents Amrapurs Belize Corozal Road, Orange Walk Town BJET's Financial Services Limited 94 Commerce Street, Dangriga Town, Stann Creek District, Belize Business Box Ecumenical Drive, Dangriga Town Caribbean Spa Services Placencia Village, Stann Creek District, Belize Casa Café 46 Forest Drive, Belmopan City, Cayo District Charlton's Cable 9 George Price Street, Punta Gorda Town, Toledo District Charlton's Cable Bella Vista, Toledo District Diversified Life Solutions 39 Albert Street West, Belize City Doony’s 57 Albert Street, Belize City Doony's Instant Loan Ltd. 8 Park Street South, Corozal District Ecabucks 15 Corner George and Orange Street, Belize City Ecabucks (X-treme Geeks, San Pedro) Corner Pescador Drive and Caribena Street, San Pedro Town, Ambergris Caye EMJ's Jewelry Placencia Village, Stann Creek District, Belize Escalante's Service Station Co. Ltd. Savannah Road, Independence Village Havana Pharmacy 22 Havana Street, Dangriga Town Hotel Coastal Bay Pescador Drive, San Pedro Town i Signature Designs 42 George Price Highway, Santa Elena Town, Cayo District Joyful Inn 49 Main Middle Street, Punta Gorda Town Landy's And Sons 141 Belize Corozal Road, Orange Walk Town Low's Supermarket Mile 8 ½ Philip Goldson Highway, Ladyville Village, Belize District Mahung’s Corner North/Main Streets, Punta Gorda Town Medical Health Supplies Pharmacy 1 Street South, Corozal Town Misericordia De Dios 27 Guadalupe Street, Orange Walk Town Paz Villas Pescador Drive, San Pedro Town Pomona Service Center Ltd. -

Biosecurity Risk Assessment

An Invasive Risk Assessment Framework for New Animal and Plant-based Production Industries RIRDC Publication No. 11/141 RIRDCInnovation for rural Australia An Invasive Risk Assessment Framework for New Animal and Plant-based Production Industries by Dr Robert C Keogh February 2012 RIRDC Publication No. 11/141 RIRDC Project No. PRJ-007347 © 2012 Rural Industries Research and Development Corporation. All rights reserved. ISBN 978-1-74254-320-8 ISSN 1440-6845 An Invasive Risk Assessment Framework for New Animal and Plant-based Production Industries Publication No. 11/141 Project No. PRJ-007347 The information contained in this publication is intended for general use to assist public knowledge and discussion and to help improve the development of sustainable regions. You must not rely on any information contained in this publication without taking specialist advice relevant to your particular circumstances. While reasonable care has been taken in preparing this publication to ensure that information is true and correct, the Commonwealth of Australia gives no assurance as to the accuracy of any information in this publication. The Commonwealth of Australia, the Rural Industries Research and Development Corporation (RIRDC), the authors or contributors expressly disclaim, to the maximum extent permitted by law, all responsibility and liability to any person, arising directly or indirectly from any act or omission, or for any consequences of any such act or omission, made in reliance on the contents of this publication, whether or not caused by any negligence on the part of the Commonwealth of Australia, RIRDC, the authors or contributors. The Commonwealth of Australia does not necessarily endorse the views in this publication. -

Democracy in the Caribbean a Cause for Concern

DEMOCRACY IN THE CARIBBEAN A CAUSE FOR CONCERN Douglas Payne April 7, 1995 Policy Papers on the Americas Democracy in the Caribbean A Cause for Concern Douglas W. Payne Policy Papers on the Americas Volume VI Study 3 April 7, 1995 CSIS Americas Program The Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS), founded in 1962, is an independent, tax-exempt, public policy research institution based in Washington, DC. The mission of CSIS is to advance the understanding of emerging world issues in the areas of international economics, politics, security, and business. It does so by providing a strategic perspective to decision makers that is integrative in nature, international in scope, anticipatory in timing, and bipartisan in approach. The Center's commitment is to serve the common interests and values of the United States and other countries around the world that support representative government and the rule of law. * * * CSIS, as a public policy research institution, does not take specific policy positions. Accordingly, all views, positions, and conclusions expressed in this report should be understood to be solely those of the authors. © 1995 by the Center for Strategic and International Studies. This study was prepared under the aegis of the CSIS Policy Papers on the Americas series. Comments are welcome and should be directed to: Joyce Hoebing CSIS Americas Program 1800 K Street, NW Washington, DC 20006 Phone: (202) 775-3180 Fax: (202) 775-3199 Contents Preface .....................................................................................................................................................