Download This PDF File

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Adapting Marriage: Law Versus Custom in Early Modern English

ADAPTING MARRIAGE: LAW VERSUS CUSTOM IN EARLY MODERN ENGLISH PLAYS by Jennifer Dawson Kraemer APPROVED BY SUPERVISORY COMMITTEE: ___________________________________________ Dr. Jessica C. Murphy, Chair ___________________________________________ Dr. Pamela Gossin ___________________________________________ Dr. Adrienne L. McLean ___________________________________________ Dr. Gerald L. Soliday Copyright 2018 Jennifer Dawson Kraemer All Rights Reserved For my family whose patience and belief in me allowed me to finish this dissertation. There were many appointments, nutritious dinners, and special outings foregone over the course of graduate school and dissertation writing, but you all understood and supported me nonetheless. ADAPTING MARRIAGE: LAW VERSUS CUSTOM IN EARLY MODERN ENGLISH PLAYS by JENNIFER DAWSON KRAEMER, BA, MA DISSERTATION Presented to the Faculty of The University of Texas at Dallas in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN HUMANITIES – STUDIES IN LITERATURE MAJOR IN STUDIES IN LITERATURE THE UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS AT DALLAS August 2018 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The inspiration for this dissertation can best be described as a kind of coalescence of droplets rather than a seed that was planted and grew. For these droplets to fuse at all instead of evaporating, I have the members of my dissertation committee to thank. Dr. Gerald L. Soliday first introduced me to exploring literature through the lens of historical context while I was pursuing my master’s degree. To Dr. Adrienne McLean, I am immensely grateful for her willingness to help supervise a non-traditional adaptation project. Dr. Pamela Gossin has been a trusted advisor for a long time, and her vast and diverse range of academic interests inspired me to attempt this fusion of adaptation theory and New Historicism. -

Biography Cast in Irony: Caveats, Stylization, and Indeterminacy in the Biographical History Plays of Tom Stoppard and Michael Frayn, Written by Christopher M

BIOGRAPHY CAST IN IRONY: CAVEATS, STYLIZATION, AND INDETERMINACY IN THE BIOGRAPHICAL HISTORY PLAYS OF TOM STOPPARD AND MICHAEL FRAYN by CHRISTOPHER M. SHONKA B.A. Creighton University, 1997 M.F.A. Temple University, 2000 A thesis submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Colorado in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Theatre 2010 This thesis entitled: Biography Cast in Irony: Caveats, Stylization, and Indeterminacy in the Biographical History Plays of Tom Stoppard and Michael Frayn, written by Christopher M. Shonka, has been approved for the Department of Theatre Dr. Merrill Lessley Dr. James Symons Date The final copy of this thesis has been examined by the signatories, and we Find that both the content and the form meet acceptable presentation standards Of scholarly work in the above mentioned discipline. iii Shonka, Christopher M. (Ph.D. Theatre) Biography Cast in Irony: Caveats, Stylization, and Indeterminacy in the Biographical History Plays of Tom Stoppard and Michael Frayn Thesis directed by Professor Merrill J. Lessley; Professor James Symons, second reader Abstract This study examines Tom Stoppard and Michael Frayn‘s incorporation of epistemological themes related to the limits of historical knowledge within their recent biography-based plays. The primary works that are analyzed are Stoppard‘s The Invention of Love (1997) and The Coast of Utopia trilogy (2002), and Frayn‘s Copenhagen (1998), Democracy (2003), and Afterlife (2008). In these plays, caveats, or warnings, that illustrate sources of historical indeterminacy are combined with theatrical stylizations that overtly suggest the authors‘ processes of interpretation and revisionism through an ironic distancing. -

THE DOMESTIC DRAMA of THOMAS DEKKER, 1599-1621 By

CHALLENGING THE HOMILETIC TRADITION: THE DOMESTIC DRAMA OF THOMAS DEKKER, 1599-1621 By VIVIANA COMENSOLI B.A.(Hons.), Simon Fraser University, 1975 M.A., Simon Fraser University, 1979 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES (Department of English) We accept, this thesis as conforming to the required standard THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA December 1984 (js) Viviana Comensoli, 1984 In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for reference and study. I further agree that permission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the head of my department or by his or her representatives. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. Department of The University of British Columbia 1956 Main Mall Vancouver, Canada V6T 1Y3 DE-6 (3/81) ABSTRACT The dissertation reappraises Thomas Dekker's dramatic achievement through an examination of his contribution to the development of Elizabethan-Jacobean domestic drama. Dekker's alterations and modifications of two essential features of early English domestic drama—the homiletic pattern of sin, punishment, and repentance, which the genre inherited from the morality tradition, and the glorification of the cult of domesticity—attest to a complex moral and dramatic vision which critics have generally ignored. In Patient Grissil, his earliest extant domestic play, which portrays ambivalently the vicissitudes of marital and family life, Dekker combines an allegorical superstructure with a realistic setting. -

Realism in Euripides

chapter 27 Realism in Euripides Michael Lloyd Realism as a literary mode is relevant to Euripides in both a broader and a nar- rower sense. His plays are realistic in the broader sense of representing actions which in general observe the laws of nature. They contrast in this with the plays of Aristophanes, in which it is possible to fly to heaven on a dung bee- tle (Peace), build a city in the air (Birds), or interact with dead poets in the underworld (Frogs). Place, time, and character in Euripides are relatively con- sistent and coherent. People and things follow continuous paths through time and space. This contrasts with Aristophanes’ more flexible treatment (e.g. in Acharnians or Clouds), and with his frequent indifference to consistency of character.1 Any attempt to distinguish realistic from non-realistic literature or art clearly depends on the belief that ‘representation’ and ‘reality’ are usable concepts, if not necessarily easy to define or the same in all cultural contexts.2 Euripides resembles Sophocles in being a realist in this broader sense, but also invites interpretation in terms of realism as it developed as a literary and artistic movement in the third quarter of the nineteenth century, most self- consciously in France in the 1850s. This is a particular manifestation of what J.P. Stern calls ‘a perennial mode of representing the world’, and does not imply limiting ‘realism’ to what he calls a ‘period term’.3 George Eliot’s classic state- ment of a realist aesthetic in Adam Bede (1859) associates truthfulness with the representation of commonplace things. -

This Dissertation Has Been 61—5100 M Icrofilm Ed Exactly As Received

This dissertation has been 61—5100 microfilmed exactly as received LOGAN, Winford Bailey, 1919- AN INVESTIGATION OF THE THEME OF THE NEGATION OF LIFE IN AMERICAN DRAMA FROM WORLD WAR H TO 1958. The Ohio State University, Ph.D., 1961 Speech — Theater University Microfilms, Inc., Ann Arbor, Michigan AN INVESTIGATION OF THE THSiE OF THE NEGATION OF LIFE IN AMERICAN DRAMA FROM WORLD WAR II TO 1958 DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Winford Bailey Logan* B.A.* M.A. The Ohio State University 1961 Approved by Adviser Department of Speech CONTENTS CHAPTER PAGE I. INTRODUCTION 1 II. A BACKGROUND OF PHILOSOPHICAL NEGATION 5 III. A BASIS OF JUDGMENT: THE CHARACTERISTICS AND 22 SYMPTOMS OF LIFE NEGATION IV. SERIOUS DRAMA IN AMERICA PRECEDING WORLD WAR II i+2 V. THE PESSIMISM OF EUGENE O'NEILL AND AN ANALYSIS 66 OF HIS LATER PLAYS VI. TENNESSEE WILLIAMS: ANALYSES OF THE GLASS MENAGERIE. 125 A STREETCAR NAMED DESIRE AND CAMINO REAL VII. ARTHUR MILLER: ANALYSES OF DEATH OF A SALESMAN 179 AND A VIEW FRCM THE BRIDGE VIII. THE PLAYS OF WILLIAM INGE 210 IX. THE USE OF THE THEME OF LIFE NEGATION BY OTHER 233 AMERICAN WRITERS OF THE PERIOD X. CONCLUSIONS 271 BIBLIOGRAPHY 289 AUTOBIOGRAPHY 302 ii CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION Critical comment pertaining to present-day American theatre frequently has included allegations that thematic emphasis seems to lie in the areas of negation. Such attacks are supported by references to our over-use of sordidity, to the infatuation with the psychological theme and the use of characters who are emotionally and mentally disturbed, and to the absence of any element of the heroic which is normally acknowledged to be an integral portion of meaningful drama. -

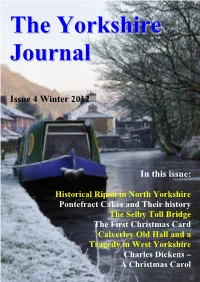

Issue 4 Winter 2012 in This Issue

TThhee YYoorrkksshhiirree JJoouurrnnaall Issue 4 Winter 2012 In this issue: Historical Ripon in North Yorkshire Pontefract Cakes and Their history The Selby Toll Bridge The First Christmas Card Calverley Old Hall and a Tragedy in West Yorkshire Charles Dickens – A Christmas Carol CChhrriissttmmaass iiss CCoommiinngg Christmas is coming, the geese are getting fat Please put a penny in the old man’s hat If you haven’t got a penny, a h’penny will do If you haven’t got a ha’penny, then God bless you! (See pages 16-17 for the story of - The first Christmas card) Old Christmas Cards often showed idealistic scenes of horses pulling stagecoaches along snowy village streets like the ones illustrated on this page. In reality travelling on stagecoaches two centuries ago was somewhat different. Charles Dickens gives an account of his journey to Bowes, situated on the northern edge of North Yorkshire, which illustrates the travelling conditions of the times. (See pages 22-27 for the story of – Charles Dickens) It was at the end of January 1838 in severe winter conations when he and his friend and illustrator, Hablot Knight Browne, nickname Phiz, caught the Glasgow Mail coach out of London. They had a difficult, two-day journey, travailing 255 miles in 27 hours up the Great North Road, which was covered in snow. They turned left into a blizzard at Scotch Corner and then along the wilds of the trans-Pennine turnpike road. The coach stopped at about 11pm on the second day at the George and New Inn at Greta Bridge on the A66. -

Fatal Desire. Women, Sexuality, and the English Stage, 1660-1720

Jean I. Marsden 2006: Fatal Desire. Women, Sexuality, and the English Stage, 1660- 1720. Ithaca and London: Cornell UP. viii + 216 pp. ISBN 9780801444470 Paula de Pando Mena Universidad de Sevilla [email protected] Jean Marsden’s Fatal Desire is a thorough analysis of Restoration drama which comes to fill a conspicuous gap in literary studies. It is probably one of the most ambitious books in scope since Derek Hughes’s influential English Drama (1996), and it certainly supplements the canonical view of Rothstein (1967) and Brown (1981), as well as the more recent works by specialists such as Owen (1996) or Canfield (2000), who primarily centred on the political dimension of the plays. This minute analysis goes from the appearance of the first English actresses after the accession of Charles II to the first decades of the eighteenth century, and focuses on the representation of female characters in both comedy and tragedy. Its aim is to complement other monographs on the lives and social consideration of actresses on the English stage (Howe’s The First English Actresses [1992] remains an unbeatable reference) or the listing of productions, performances and their reception. Marsden does this by centering her research on the resemblances between the apparently dissimilar fields of Restoration practice and contemporary film theory. The reification of women in cinema and the importance of the image as object of the desiring gaze prompt a series of parallelisms with the reaction of seventeenth and early eighteenth-century audiences to the spectacle of women on stage. According to this theory, Restoration plays were based on the concept of scopic pleasure, which is the inherently masculine visual enjoyment of a passive object. -

Quince's Questions and the Mystery of the Play Experience J. L. Styan*

Fall 1986 3 Quince's Questions and the Mystery of the Play Experience J. L. Styan* Dramatic semioticians are aware of the ripples they are causing in the classrooms and workshops across the country. Some kind of analytic tool has long been needed to enable us to talk about what an audience perceives on the stage, how it perceives it, and how the perception is translated into a conception. Though he would hate to be called a semiotician, John Russell Brown was right to emphasize years ago that a play-reader is a different animal from a playgoer and that his perceptions will therefore very likely be different. More recently, Patrice Pavis was right to remind us that the relationship between text and performance is not one of simple implication, but rather what he calls 'dialectical,' whereby the actor comments on and argues with the text (146); and some years ago I found myself suggesting that Shakespeare's text prompted a 'controlled freedom' of improvisation for his actor (Styan 199). In other fields, Keir Elam and others are right to find our ways of regarding the use of scene and costume, space and light, as too impressionistic: we need to know more of how these features are defined by conventional patterns, social behavior, or aesthetic rules. Above all, it needs to be said how important it is to understand the theatre as a process of communication, one which insists that the audience makes its contribution to the creation of the play by its interpretation of the signs and signals from the stage, where everything seen and heard must acquire the strength of convention. -

Modernism, Anti-Theatricality, and Irish Drama Michael Bogucki A

BRUTAL PHANTOMS: Modernism, Anti-Theatricality, and Irish Drama Michael Bogucki A dissertation submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of English and Comparative Literature. Chapel Hill 2009 Approved by: John McGowan Nicholas Allen Gregory Flaxman Megan Matchinske Toril Moi ©2009 Michael Bogucki All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT MICHAEL BOGUCKI: Brutal Phantoms: Modernism, Ireland, and Anti-Theatrical Drama (Under the direction of John McGowan and Nicholas Allen) This dissertation analyzes the fate of realist theatrical conventions in the work of George Moore, John M. Synge, Bernard Shaw, W.B. Yeats, and James Joyce. These writers reconfigured the conditions of theater so as to avoid the debased forms of expression they associated with the performance practices of British touring companies and with commercialism generally. Each playwright experimented with texts, performers, audiences, and theater spaces so as to foreground and criticize those aspects of the material stage they found inauthentic, sensational, and excessive. Recent narratives of the relationship between modernism and theater have rightly focused on the way literary or imagist avant-gardes generate new modes of innovative, radicalized theatrical display by, in effect, taking the stage outdoors or into the text. By locating these writers‘ anxieties about theatricality in the overlapping histories of the Irish Revival and the economies of transatlantic theater production, I argue that the theater itself was often the site of its own most sophisticated critiques, and that the strategies these late naturalist and early modernist writers develop resonate with contemporary questions in Irish studies and performance theory about the status of live theater. -

Serious Domestic Drama As Tragedy : a Study of the Protagonist Charles Turney

University of Richmond UR Scholarship Repository Master's Theses Student Research 1959 Serious domestic drama as tragedy : a study of the protagonist Charles Turney Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.richmond.edu/masters-theses Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Turney, Charles, "Serious domestic drama as tragedy : a study of the protagonist" (1959). Master's Theses. 1352. https://scholarship.richmond.edu/masters-theses/1352 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Research at UR Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of UR Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SERIOUS DOMESTIC DRAMA AS TRAGEDY: A STUDY OF THE PROTAGONIST A THESIS P�esented 1n, Partial Fulfillment or the Requirements for the Degttee Master of Arte 1n the Graduate· School of .The Un1v,er.s1.tJ'. o� Richmond CHARLES TURUEY, B. A. THE UNIVERSITY OF RICHMOND 1969 Approved tor the Departmen� of English and the Graduate Sohool by �J.d:a.J.LJesior-· ot English-- /??:/h--l ;a:_ Dean of the Graalate-- School PREFACE A classification of a group of plays by different authors written at different times under a general title ot domestic drama is of necessity arbitrary. A further olassit1oation of certain of these plays as tragedies and others as problem plays is also arbitrary; but while there may be 11ttle objection to the first classifi• cation, it 1s almost certain that some objection will arise over the second because there is a suggestion that those plays not included as tragedies must have some fault and are not as good as the ones selected. -

Black and White and Red All Over: Bloody Performance in Theatre and Law

23 GARY WATT Black and White and Red All Over: Bloody Performance in Theatre and Law Legal ritual is for the most part performed in black and white – not only with black letter texts, but also by means of the black textiles that make up lawyers' gowns and suits. Only occasionally, but then most significantly, the law has allowed the bloody hue of red to seep through; most notably in the sanguine form of a red wax seal. There is nothing more significant than blood – it is the original sign – and the Latin for "small sign" gives us the word "seal." Small in size it may be, but in legal documentary contexts it is a concentration or distillation of the great sign ('signum') of blood. A red seal set on a legal form shows that the law's social performance has operative power. As the seal of red wax on documentary formality is, or was, the preeminent signifier of the ritual performance of a legal text, so in terms of textile, the bloody red of the judge's silk signals the office of judgment. It is not by accident that the lead prosecutor, on the fateful final day of the trial of Charles I, was, "for the first time, robed in red" (Wedgwood 1964, 154). The red of judgment contrasts with the black and white office of advocacy. I am here recalling a description of lawyers that Jonathan Swift placed in the mouth of Captain Lemuel Gulliver. Lawyers, he said, are "a society of men among us, bred up from their youth in the art of proving, by words multiplied for the purpose, that white is black, and black is white, according as they are paid" (Swift 1726, IV.5). -

The Nature of Audience Response in Medieval and Early Modern Drama Seeks to Interrogate and Explore

Duquesne University Duquesne Scholarship Collection Electronic Theses and Dissertations Spring 2014 Stages of Belief: The aN ture of Audience Response in Medieval and Early Modern Drama Rebecca Cepek Follow this and additional works at: https://dsc.duq.edu/etd Recommended Citation Cepek, R. (2014). Stages of Belief: The aN ture of Audience Response in Medieval and Early Modern Drama (Doctoral dissertation, Duquesne University). Retrieved from https://dsc.duq.edu/etd/387 This Immediate Access is brought to you for free and open access by Duquesne Scholarship Collection. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Duquesne Scholarship Collection. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STAGES OF BELIEF: THE NATURE OF AUDIENCE RESPONSE IN MEDIEVAL AND EARLY MODERN DRAMA A Dissertation Submitted to the McAnulty College and Graduate School of Liberal Arts Duquesne University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy By Rebecca Cepek May 2014 Copyright by Rebecca Cepek 2014 STAGES OF BELIEF: THE NATURE OF AUDIENCE RESPONSE IN MEDIEVAL AND EARLY MODERN DRAMA By Rebecca Cepek Approved March 18, 2014 ________________________________ ________________________________ Anne Brannen, Ph.D. Laura Engel, Ph.D. Associate Professor of English Associate Professor of English (Dissertation Director) (Committee Member) ________________________________ ________________________________ Stuart M. Kurland, Ph.D. John E. Lane, Jr., M.A. Associate