1 Adapting True Crime: George Wilkins's the Miseries of Inforst

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Yorkshire Tragedy by William Shakespeare (Apocrypha)

A Yorkshire Tragedy by William Shakespeare (Apocrypha) This etext was produced by Tony Adam. Shakespeare, William. A Yorkshire Tragedy. Not So New as Lamentable and True. In C.F. Tucker Brooke, ed., The Shakespeare Apocrypha (Oxford, 1918). ALL'S ONE, OR, ONE OF THE FOUR PLAYS IN ONE, CALLED A YORK-SHIRE TRAGEDY AS IT WAS PLAYED BY THE KING'S MAJESTY'S PLAYERS. Dramatis Personae. Husband. Master of a College. Knight, a Justice of Peace. Oliver, Ralph, Samuel, serving-men. Other Servants, and Officers. page 1 / 56 Wife. Maid-servant. A little Boy. SCENE I. A room in Calverly Hall. [Enter Oliver and Ralph, two servingmen.] OLIVER. Sirrah Ralph, my young Mistress is in such a pitiful passionate humor for the long absence of her love-- RALPH. Why, can you blame her? why, apples hanging longer on the tree then when they are ripe makes so many fallings; viz., Mad wenches, because they are not gathered in time, are fain to drop of them selves, and then tis Common you know for every man to take em up. OLIVER. Mass, thou sayest true, Tis common indeed: but, sirrah, is neither our young master returned, nor our fellow Sam come from London? RALPH. page 2 / 56 Neither of either, as the Puritan bawd says. Slidd, I hear Sam: Sam's come, her's! Tarry! come, yfaith, now my nose itches for news. OLIVER. And so does mine elbow. [Sam calls within. Where are you there?] SAM. Boy, look you walk my horse with discretion; I have rid him simply. I warrant his skin sticks to his back with very heat: if a should catch cold and get the Cough of the Lungs I were well served, were I not? [Enter Sam. -

Adapting Marriage: Law Versus Custom in Early Modern English

ADAPTING MARRIAGE: LAW VERSUS CUSTOM IN EARLY MODERN ENGLISH PLAYS by Jennifer Dawson Kraemer APPROVED BY SUPERVISORY COMMITTEE: ___________________________________________ Dr. Jessica C. Murphy, Chair ___________________________________________ Dr. Pamela Gossin ___________________________________________ Dr. Adrienne L. McLean ___________________________________________ Dr. Gerald L. Soliday Copyright 2018 Jennifer Dawson Kraemer All Rights Reserved For my family whose patience and belief in me allowed me to finish this dissertation. There were many appointments, nutritious dinners, and special outings foregone over the course of graduate school and dissertation writing, but you all understood and supported me nonetheless. ADAPTING MARRIAGE: LAW VERSUS CUSTOM IN EARLY MODERN ENGLISH PLAYS by JENNIFER DAWSON KRAEMER, BA, MA DISSERTATION Presented to the Faculty of The University of Texas at Dallas in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN HUMANITIES – STUDIES IN LITERATURE MAJOR IN STUDIES IN LITERATURE THE UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS AT DALLAS August 2018 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The inspiration for this dissertation can best be described as a kind of coalescence of droplets rather than a seed that was planted and grew. For these droplets to fuse at all instead of evaporating, I have the members of my dissertation committee to thank. Dr. Gerald L. Soliday first introduced me to exploring literature through the lens of historical context while I was pursuing my master’s degree. To Dr. Adrienne McLean, I am immensely grateful for her willingness to help supervise a non-traditional adaptation project. Dr. Pamela Gossin has been a trusted advisor for a long time, and her vast and diverse range of academic interests inspired me to attempt this fusion of adaptation theory and New Historicism. -

Article (Published Version)

Article 'Our Other Shakespeare'? Thomas Middleton and the Canon ERNE, Lukas Christian Reference ERNE, Lukas Christian. 'Our Other Shakespeare'? Thomas Middleton and the Canon. Modern Philology, 2010, vol. 107, no. 3, p. 493-505 Available at: http://archive-ouverte.unige.ch/unige:14484 Disclaimer: layout of this document may differ from the published version. 1 / 1 492 MODERN PHILOLOGY absorbs and reinterprets a vast array of Renaissance cultural systems. "Our other Shakespeare": Thomas Middleton What is outside and what is inside, the corporeal world and the mental and the Canon one, are "similar"; they are vivified and governed by the divine spirit in Walker's that emanates from the Sun, "the body of the anima mundi" LUKAS ERNE correct interpretation. 51 Campanella's philosopher has a sacred role, in that by fathoming the mysterious dynamics of the real through scien- University of Geneva tific research, he performs a religious ritual that celebrates God's infi- nite wisdom. To T. S. Eliot, Middleton was the author of "six or seven great plays." 1 It turns out that he is more than that. The dramatic canon as defined by the Oxford Middleton—under the general editorship of Gary Taylor and John Lavagnino, leading a team of seventy-five contributors—con- sists of eighteen sole-authored plays, ten extant collaborative plays, and two adaptations of plays written by someone else. The thirty plays, writ ten for at least seven different companies, cover the full generic range of early modern drama: eight tragedies, fourteen comedies, two English history plays, and six tragicomedies. These figures invite comparison with Shakespeare: ten tragedies, thirteen comedies, ten or (if we count Edward III) eleven histories, and five tragicomedies or romances (if we add Pericles and < Two Noble Kinsmen to those in the First Folio). -

Biography Cast in Irony: Caveats, Stylization, and Indeterminacy in the Biographical History Plays of Tom Stoppard and Michael Frayn, Written by Christopher M

BIOGRAPHY CAST IN IRONY: CAVEATS, STYLIZATION, AND INDETERMINACY IN THE BIOGRAPHICAL HISTORY PLAYS OF TOM STOPPARD AND MICHAEL FRAYN by CHRISTOPHER M. SHONKA B.A. Creighton University, 1997 M.F.A. Temple University, 2000 A thesis submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Colorado in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Theatre 2010 This thesis entitled: Biography Cast in Irony: Caveats, Stylization, and Indeterminacy in the Biographical History Plays of Tom Stoppard and Michael Frayn, written by Christopher M. Shonka, has been approved for the Department of Theatre Dr. Merrill Lessley Dr. James Symons Date The final copy of this thesis has been examined by the signatories, and we Find that both the content and the form meet acceptable presentation standards Of scholarly work in the above mentioned discipline. iii Shonka, Christopher M. (Ph.D. Theatre) Biography Cast in Irony: Caveats, Stylization, and Indeterminacy in the Biographical History Plays of Tom Stoppard and Michael Frayn Thesis directed by Professor Merrill J. Lessley; Professor James Symons, second reader Abstract This study examines Tom Stoppard and Michael Frayn‘s incorporation of epistemological themes related to the limits of historical knowledge within their recent biography-based plays. The primary works that are analyzed are Stoppard‘s The Invention of Love (1997) and The Coast of Utopia trilogy (2002), and Frayn‘s Copenhagen (1998), Democracy (2003), and Afterlife (2008). In these plays, caveats, or warnings, that illustrate sources of historical indeterminacy are combined with theatrical stylizations that overtly suggest the authors‘ processes of interpretation and revisionism through an ironic distancing. -

THE DOMESTIC DRAMA of THOMAS DEKKER, 1599-1621 By

CHALLENGING THE HOMILETIC TRADITION: THE DOMESTIC DRAMA OF THOMAS DEKKER, 1599-1621 By VIVIANA COMENSOLI B.A.(Hons.), Simon Fraser University, 1975 M.A., Simon Fraser University, 1979 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES (Department of English) We accept, this thesis as conforming to the required standard THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA December 1984 (js) Viviana Comensoli, 1984 In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for reference and study. I further agree that permission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the head of my department or by his or her representatives. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. Department of The University of British Columbia 1956 Main Mall Vancouver, Canada V6T 1Y3 DE-6 (3/81) ABSTRACT The dissertation reappraises Thomas Dekker's dramatic achievement through an examination of his contribution to the development of Elizabethan-Jacobean domestic drama. Dekker's alterations and modifications of two essential features of early English domestic drama—the homiletic pattern of sin, punishment, and repentance, which the genre inherited from the morality tradition, and the glorification of the cult of domesticity—attest to a complex moral and dramatic vision which critics have generally ignored. In Patient Grissil, his earliest extant domestic play, which portrays ambivalently the vicissitudes of marital and family life, Dekker combines an allegorical superstructure with a realistic setting. -

Realism in Euripides

chapter 27 Realism in Euripides Michael Lloyd Realism as a literary mode is relevant to Euripides in both a broader and a nar- rower sense. His plays are realistic in the broader sense of representing actions which in general observe the laws of nature. They contrast in this with the plays of Aristophanes, in which it is possible to fly to heaven on a dung bee- tle (Peace), build a city in the air (Birds), or interact with dead poets in the underworld (Frogs). Place, time, and character in Euripides are relatively con- sistent and coherent. People and things follow continuous paths through time and space. This contrasts with Aristophanes’ more flexible treatment (e.g. in Acharnians or Clouds), and with his frequent indifference to consistency of character.1 Any attempt to distinguish realistic from non-realistic literature or art clearly depends on the belief that ‘representation’ and ‘reality’ are usable concepts, if not necessarily easy to define or the same in all cultural contexts.2 Euripides resembles Sophocles in being a realist in this broader sense, but also invites interpretation in terms of realism as it developed as a literary and artistic movement in the third quarter of the nineteenth century, most self- consciously in France in the 1850s. This is a particular manifestation of what J.P. Stern calls ‘a perennial mode of representing the world’, and does not imply limiting ‘realism’ to what he calls a ‘period term’.3 George Eliot’s classic state- ment of a realist aesthetic in Adam Bede (1859) associates truthfulness with the representation of commonplace things. -

Signs of the Crimes: Topography, Murder, and Early Modern Domestic Tragedy

SIGNS OF THE CRIMES: TOPOGRAPHY, MURDER, AND EARLY MODERN DOMESTIC TRAGEDY MARISSA GREENBERG, UNIVERSITY OF NEW MEXICO [I]t seems to have been the constant practice of the dramatists of that day, to avail themselves (like ballad-makers) of any circumstances of the kind, which attracted attention, in order to construct them into a play, often treating the subject merely as a dramatic narrative of a known occurrence, without embellishing, or aiding it with the ornaments of invention. — John Payne Collier, The History of English Dramatic Poetry (1831) Police are toning down the bright yellow street signs used in the Brit- ish capital to mark the sites of murders, robberies and assaults following complaints that they increase public fear of violent crimes. - The Advertiser (2002) In the century following John Payne Collier's discussion of domestic trag- edies as a generic group, each of which originates "in a recent tragical incident," critics have continued to comment upon the plays' fidelity to reality (Collier 3:50).' In 1906 John Addington Symonds noted the plays' "sombre realistic detail" (329); in 1975 Andrew Clark wrote about their "realism of the most unrefined and sensational kind" (155); in the final decade of the twentieth cen- tury Frances E. Dolan discussed their "grim journalistic detail" ("Gender" 211) and Peter Holbrook their "quasi-documentary feel" (93); and at the turn of the twenty-first century, almost 170 years after Collier, Richard Helgerson remains fascinated by domestic tragedy's "extraordinary realism" (2). Though they share 1 I am enormously indebted to Margreta de Grazia, whose comments on earlier versions of this essay helped considerably to shape its final form. -

This Dissertation Has Been 61—5100 M Icrofilm Ed Exactly As Received

This dissertation has been 61—5100 microfilmed exactly as received LOGAN, Winford Bailey, 1919- AN INVESTIGATION OF THE THEME OF THE NEGATION OF LIFE IN AMERICAN DRAMA FROM WORLD WAR H TO 1958. The Ohio State University, Ph.D., 1961 Speech — Theater University Microfilms, Inc., Ann Arbor, Michigan AN INVESTIGATION OF THE THSiE OF THE NEGATION OF LIFE IN AMERICAN DRAMA FROM WORLD WAR II TO 1958 DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Winford Bailey Logan* B.A.* M.A. The Ohio State University 1961 Approved by Adviser Department of Speech CONTENTS CHAPTER PAGE I. INTRODUCTION 1 II. A BACKGROUND OF PHILOSOPHICAL NEGATION 5 III. A BASIS OF JUDGMENT: THE CHARACTERISTICS AND 22 SYMPTOMS OF LIFE NEGATION IV. SERIOUS DRAMA IN AMERICA PRECEDING WORLD WAR II i+2 V. THE PESSIMISM OF EUGENE O'NEILL AND AN ANALYSIS 66 OF HIS LATER PLAYS VI. TENNESSEE WILLIAMS: ANALYSES OF THE GLASS MENAGERIE. 125 A STREETCAR NAMED DESIRE AND CAMINO REAL VII. ARTHUR MILLER: ANALYSES OF DEATH OF A SALESMAN 179 AND A VIEW FRCM THE BRIDGE VIII. THE PLAYS OF WILLIAM INGE 210 IX. THE USE OF THE THEME OF LIFE NEGATION BY OTHER 233 AMERICAN WRITERS OF THE PERIOD X. CONCLUSIONS 271 BIBLIOGRAPHY 289 AUTOBIOGRAPHY 302 ii CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION Critical comment pertaining to present-day American theatre frequently has included allegations that thematic emphasis seems to lie in the areas of negation. Such attacks are supported by references to our over-use of sordidity, to the infatuation with the psychological theme and the use of characters who are emotionally and mentally disturbed, and to the absence of any element of the heroic which is normally acknowledged to be an integral portion of meaningful drama. -

Newsletter Vol

The Shakespeare Oxford O Newsletter Vol. 50, No. 4 Published by the Shakespeare Oxford Fellowship Fall 2014 Whittemore Keynotes; McNeil and Altrocchi Honored at Madison SOF Conference by Howard Schumann " The first authorship conference sponsored by the Shakespeare Oxford Fellowship was held at the Overture Center in Madison, Wisconsin, from September 11 to 14, 2014. The keynote address was presented by Hank Whittemore. The Oxfordian of the Year award was given to Alex McNeil, Shakespeare Oxford Newsletter editor and former president of the Shakespeare Fellowship. An Oxfordian Achievement Award was given to Paul Altrocchi, MD. McNeil’s award was presented by former SOF President John Hamill and President Tom Regnier. Hamill said that McNeil had helped make the 2013 unification of the Shakespeare Fellowship and the Shakespeare Oxford Society a “reality.” Regnier lauded him as the “conscience of the movement and one of its rocks.” Accepting the award, McNeil thanked Hamill and Regnier for their leadership in effecting the merger. He said that he is optimistic about the future even though “there is little consensus about all aspects.” His advice to attendees was “there should always be a shred of doubt. Don’t think you know everything.” Altrocchi’s award was presented by Hank Paul Altrocchi, MD Whittemore, who praised Altrocchi as a physician, artist, " and indomitable seeker of truth. Altrocchi is a former Daniel stated that APT has performed Romeo and trustee of the Shakespeare Fellowship, and has written or Juliet seven times and A Midsummer -

Shakespeare Seminar

Shakespeare Seminar Deutsche Shakespeare-Gesellschaft Ausgabe 8 (2010) Shakespeare and the City: The Negotiation of Urban Spaces in Shakespeare’s Plays www.shakespeare-gesellschaft.de/publikationen/seminar/ausgabe2010 Shakespeare Seminar 8 (2010) EDITORS The Shakespeare Seminar is published under the auspices of the Deutsche Shakespeare-Gesellschaft, Weimar, and edited by: Dr Christina Wald, Universität Augsburg, Fachbereich Anglistik und Amerikanistik, Universitätsstr. 10, D-86159 Augsburg ([email protected]) Dr Felix Sprang, Universität Hamburg, Institut für Anglistik und Amerikanistik, Von-Melle-Park 6, D-20146 Hamburg ([email protected]) PUBLICATIONS FREQUENCY Shakespeare Seminar Online is a free annual online journal. It documents papers presented at the Academic Seminar panel of the spring conferences of the Deutsche Shakespeare-Gesellschaft. It is intended as a publication platform especially for the younger generation of scholars. You can find the current call for papers on our website. INTERNATIONAL STANDARD SERIAL NUMBER ISSN 1612-8362 © Copyright 2010 Deutsche Shakespeare-Gesellschaft e.V. CONTENTS Introduction by Christina Wald and Felix Sprang ............................................................................... 2 Timon’s Athens and the Wilderness of Philosophy by Galena Hashhozheva ................................................................................................. 3 Shakespeare at the Fringe: Playing the Metropolis by Yvonne Zips ............................................................................................................. -

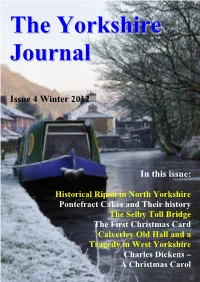

Issue 4 Winter 2012 in This Issue

TThhee YYoorrkksshhiirree JJoouurrnnaall Issue 4 Winter 2012 In this issue: Historical Ripon in North Yorkshire Pontefract Cakes and Their history The Selby Toll Bridge The First Christmas Card Calverley Old Hall and a Tragedy in West Yorkshire Charles Dickens – A Christmas Carol CChhrriissttmmaass iiss CCoommiinngg Christmas is coming, the geese are getting fat Please put a penny in the old man’s hat If you haven’t got a penny, a h’penny will do If you haven’t got a ha’penny, then God bless you! (See pages 16-17 for the story of - The first Christmas card) Old Christmas Cards often showed idealistic scenes of horses pulling stagecoaches along snowy village streets like the ones illustrated on this page. In reality travelling on stagecoaches two centuries ago was somewhat different. Charles Dickens gives an account of his journey to Bowes, situated on the northern edge of North Yorkshire, which illustrates the travelling conditions of the times. (See pages 22-27 for the story of – Charles Dickens) It was at the end of January 1838 in severe winter conations when he and his friend and illustrator, Hablot Knight Browne, nickname Phiz, caught the Glasgow Mail coach out of London. They had a difficult, two-day journey, travailing 255 miles in 27 hours up the Great North Road, which was covered in snow. They turned left into a blizzard at Scotch Corner and then along the wilds of the trans-Pennine turnpike road. The coach stopped at about 11pm on the second day at the George and New Inn at Greta Bridge on the A66. -

Editorial Treatment of the Shakespeare Apocrypha

Egan, Gabriel. 2004j. 'Editorial Treatment of the Shakespeare Apocrypha, 1664-1737': A Paper Delivered at the Conference 'Leviathan to Licensing Act (The Long Restoration, 1650-1737): Theatre, Print and Their Contexts' at Loughborough University, 15-16 September Editorial treatment of the Shakespeare apocrypha, 1664-1737 by Gabriel Egan The third edition (F3) of the collected plays of Shakespeare appeared in 1663, and to its second issue the following year was added a particularly disreputable group of plays comprised Pericles, The London Prodigal, Sir John Oldcastle, A Yorkshire Tragedy, Thomas Lord Cromwell, The Puritan, and Locrine. Of these, only Pericles remains in the accepted Shakespeare canon, the edges of which are imprecisely defined. (At the moment it is unclear whether Edward 3 is in or out.) The landmark event for defining the Shakespeare canon was the publication of the 1623 First Folio (F1), with which, as Stanley Wells and Gary Taylor put it, "the substantive history of Shakespeare's dramatic texts virtually comes to an end" (Wells et al. 1987, 52). Only one more genuine Shakespeare play was first printed after 1623: The Two Noble Kinsmen, which appeared in a quarto of 1634 whose title-page attributed it to Shakespeare and Fletcher, "Gent[lemen]" (Fletcher & Shakespeare 1634, A1r). Perhaps inclusion in F1 should not be an important criterion for us and we should put more weight on such facts as Pericles's appearing in quarto in 1609 with a titlepage that claimed it was by William Shakespeare. But the same can be said for other plays that got added to the Folio in 1663: The London Prodigal, Sir John Oldcastle, and A Yorkshire Tragedy were printed in early quartos that named their author as William Shakespeare and the other three in quartos that named "W.S".