Issue 4 Winter 2012 in This Issue

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Scott Wilson Scotland: a History Volume 11 the Interchange Years

Doc 12.56: Scott Wilson Scotland: A History: Vol 11: The Interchange Years 2005-2009 JP McCafferty Scott Wilson Scotland: A History Volume 11 The Interchange Years 2005-2009 Transcribed and edited from ‘Interchange’ JP McCafferty 1 Doc 12.56: Scott Wilson Scotland: A History: Vol 11: The Interchange Years 2005-2009 JP McCafferty Significant or notable projects, people and events are highlighted as follows for ease of reference:- Projects/Disciplines People Issue/Date Actions Contents Background ......................................................................................................................................... 12 Interchange ......................................................................................................................................... 12 JP McCafferty [Find Issues 1-40; Fix Pics P 16, 21; Fix P 68 150 Header 2]...................................... 12 Interchange 41 [21.10.2005] ............................................................................................................... 13 The Environment section in Edinburgh is delighted to welcome Nicholas Whitelaw ..................... 13 Interchange 42 [28.10.2005] ............................................................................................................... 13 S W Renewable Energy at British Wind Energy Association [Wright; Morrison] ............................. 13 Interchange 43 [4.11.2005] ................................................................................................................. 14 Jobs: Civil -

Road Investment Strategy 2: 2020-2025

Road Investment Strategy 2: 2020–2025 March 2020 CORRECTION SLIP Title: Road Investment Strategy 2: 2020-25 Session: 2019-21 ISBN: 978-1-5286-1678-2 Date of laying: 11th March 2020 Correction: Removing duplicate text on the M62 Junctions 20-25 smart motorway Text currently reads: (Page 95) M62 Junctions 20-25 – upgrading the M62 to smart motorway between junction 20 (Rochdale) and junction 25 (Brighouse) across the Pennines. Together with other smart motorways in Lancashire and Yorkshire, this will provide a full smart motorway link between Manchester and Leeds, and between the M1 and the M6. This text should be removed, but the identical text on page 96 remains. Correction: Correcting a heading in the eastern region Heading currently reads: Under Construction Heading should read: Smart motorways subject to stocktake Date of correction: 11th March 2020 Road Investment Strategy 2: 2020 – 2025 Presented to Parliament pursuant to section 3 of the Infrastructure Act 2015 © Crown copyright 2020 This publication is licensed under the terms of the Open Government Licence v3.0 except where otherwise stated. To view this licence, visit nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/ open-government-licence/version/3. Where we have identified any third party copyright information you will need to obtain permission from the copyright holders concerned. This publication is available at https://www.gov.uk/government/publications. Any enquiries regarding this publication should be sent to us at https://forms.dft.gov.uk/contact-dft-and-agencies/ ISBN 978-1-5286-1678-2 CCS0919077812 Printed on paper containing 75% recycled fibre content minimum. Printed in the UK by the APS Group on behalf of the Controller of Her Majesty’s Stationery Office. -

Isurium Brigantum

Isurium Brigantum an archaeological survey of Roman Aldborough The authors and publisher wish to thank the following individuals and organisations for their help with this Isurium Brigantum publication: Historic England an archaeological survey of Roman Aldborough Society of Antiquaries of London Thriplow Charitable Trust Faculty of Classics and the McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research, University of Cambridge Chris and Jan Martins Rose Ferraby and Martin Millett with contributions by Jason Lucas, James Lyall, Jess Ogden, Dominic Powlesland, Lieven Verdonck and Lacey Wallace Research Report of the Society of Antiquaries of London No. 81 For RWS Norfolk ‒ RF Contents First published 2020 by The Society of Antiquaries of London Burlington House List of figures vii Piccadilly Preface x London W1J 0BE Acknowledgements xi Summary xii www.sal.org.uk Résumé xiii © The Society of Antiquaries of London 2020 Zusammenfassung xiv Notes on referencing and archives xv ISBN: 978 0 8543 1301 3 British Cataloguing in Publication Data A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. Chapter 1 Introduction 1 1.1 Background to this study 1 Library of Congress Cataloguing in Publication Data 1.2 Geographical setting 2 A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the 1.3 Historical background 2 Library of Congress, Washington DC 1.4 Previous inferences on urban origins 6 The moral rights of Rose Ferraby, Martin Millett, Jason Lucas, 1.5 Textual evidence 7 James Lyall, Jess Ogden, Dominic Powlesland, Lieven 1.6 History of the town 7 Verdonck and Lacey Wallace to be identified as the authors of 1.7 Previous archaeological work 8 this work has been asserted by them in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. -

Doc // Confectionery // Download

Confectionery < PDF » 6TSHXTODZV Confectionery By - Reference Series Books LLC Feb 2012, 2012. Taschenbuch. Book Condition: Neu. 253x192x10 mm. Neuware - Source: Wikipedia. Pages: 116. Chapters: Caramel, Candy bar, Jelly bean, Marshmallow, Frutta martorana, Candy corn, Maple sugar, Knäck, Gummi bear, Praline, Jelly baby, Halva, Chewing gum, Candy desk, Cookie decorating, Marzipan, Candy pumpkin, Mozartkugel, List of candies, Turkish delight, Sherbet, Sprinkles, Indian sweets, Succade, Macaroon, Turrón, Stick candy, Karah Parshad, Polkagris, Poisoned candy scare, Marron glacé, Candy cane, Cotton candy, Jujube, Rock, Gum industry, Ice cream cone, Gummi candy, Salty liquorice, Fudge, Dulce de leche, Lollipop, Gobstopper, Hanukkah gelt, Salt water taffy, Candy apple, Marshmallow creme, Loose candy, Nonpareils, Circus Peanuts, Chikki, Cajeta, Liquorice allsorts, Butterscotch, Mint, Fondant, Churchkhela, Divinity, Cake decorating, Rock candy, Chocolate truffle, Lula's Chocolates, Gum base, Candy cigarette, Rapadura, Candied fruit, Sugar panning, Penuche, Peanut butter cup, Sponge toffee, Bulk confectionery, Maple taffy, Gibraltar rock, Coconut candy, Muisjes, Ka'í Ladrillo, Haw flakes, Jaangiri, Werther's Original, Tooth-friendly, Edible ink printing, Jordan almonds, Pastille, Pontefract cake, Hard candy, Sugar plum, Laddu, Calisson, Rum ball, Caramel apple, Imarti, Dodol, Bridge mix, Soutzoukos, Sesame seed candy, Gumdrop, Riesen, Soor ploom, Cocadas, Strela candy, Rat Candy, Gaz, Misri, Kakinada Khaja, Krówki, Sohan, Sugar paste, Bubblegum, Kettle... READ ONLINE [ 1.22 MB ] Reviews The publication is great and fantastic. It really is simplistic but surprises within the 50 % from the publication. Your daily life span will be change when you comprehensive reading this article book. -- Althea Aufderhar A top quality book along with the typeface employed was interesting to learn. -

Read PDF ~ Confectionery

ZBYPPUBXMWVA « Book \ Confectionery Confectionery Filesize: 8.76 MB Reviews It is really an incredible publication which i have possibly read. It is amongst the most incredible publication i actually have read through. I found out this pdf from my i and dad recommended this publication to discover. (Abigale Ruecker) DISCLAIMER | DMCA XOVWZ90CVKYC « Book \\ Confectionery CONFECTIONERY Reference Series Books LLC Feb 2012, 2012. Taschenbuch. Book Condition: Neu. 253x192x10 mm. Neuware - Source: Wikipedia. Pages: 116. Chapters: Caramel, Candy bar, Jelly bean, Marshmallow, Frutta martorana, Candy corn, Maple sugar, Knäck, Gummi bear, Praline, Jelly baby, Halva, Chewing gum, Candy desk, Cookie decorating, Marzipan, Candy pumpkin, Mozartkugel, List of candies, Turkish delight, Sherbet, Sprinkles, Indian sweets, Succade, Macaroon, Turrón, Stick candy, Karah Parshad, Polkagris, Poisoned candy scare, Marron glacé, Candy cane, Cotton candy, Jujube, Rock, Gum industry, Ice cream cone, Gummi candy, Salty liquorice, Fudge, Dulce de leche, Lollipop, Gobstopper, Hanukkah gelt, Salt water tay, Candy apple, Marshmallow creme, Loose candy, Nonpareils, Circus Peanuts, Chikki, Cajeta, Liquorice allsorts, Butterscotch, Mint, Fondant, Churchkhela, Divinity, Cake decorating, Rock candy, Chocolate trule, Lula's Chocolates, Gum base, Candy cigarette, Rapadura, Candied fruit, Sugar panning, Penuche, Peanut butter cup, Sponge toee, Bulk confectionery, Maple tay, Gibraltar rock, Coconut candy, Muisjes, Ka'í Ladrillo, Haw flakes, Jaangiri, Werther's Original, Tooth-friendly, -

Racewatch Bingo Are You Ready for the Racewatch Bingo?

COOKING is one big ADVENTURE Gingerbread Men INGREDIENTS 350 g plain flour 1 tsp bicarbonate of soda 2 tsp ground ginger 100 g butter 175 g light muscovado sugar 4 tbsp golden syrup 1 large egg For the decoration 1/2 cup icing sugars, smarties; METHOD Pre-heat the oven to 190C / 170C fan. Line 3 baking sheets with greaseproof paper. Measure the flour, and add it to a large mixing bowl.Weigh the butter then chop it up into a few pieces before adding it to the flour. Using your fingertips, rub in the butter until the mixture resembles fine breadcrumbs. Measure the sugar then stir it into the flour mixture with the bicarbonate of soda and ginger. Add the golden syrup.Crack the egg into a separate bowl then add it to the flour. Mix everything together until you have a smooth dough.The recipe makes quite a lot so, if you need to, divide the dough in half then roll out one half on to a lightly floured work surface until its about 5mm thick. Cut out your ginger bread men using a cutter or use any other shapes you have to hand. Place them on your baking tray.Gather up any scraps and roll out again. Repeat with the remaining dough.Bake in the oven for 10-12 minutes until they become a slightly darker shade. If your shapes are smaller, check them after 7-8 minutes. Cool slightly then lift on to a wire rack to cool.You can enjoy the ginger bread biscuits as they are or add some icing decorations. -

London to Scotland East Route Strategy March 2017 Contents 1

London to Scotland East Route Strategy March 2017 Contents 1. Introduction 1 Purpose of Route Strategies 2 Strategic themes 2 Stakeholder engagement 3 Transport Focus 3 2. The route 5 Route Strategy overview map 7 3. Current constraints and challenges 9 A safe and serviceable network 9 More free-flowing network 9 Supporting economic growth 9 An improved environment 10 A more accessible and integrated network 10 Diversionary routes 17 Maintaining the strategic road network 18 4. Current investment plans and growth potential 19 Economic context 19 Innovation 19 Investment plans 19 5. Future challenges and opportunities 25 6. Next steps 37 i R Lon ou don to Scotla te nd East London Or bital and M23 to Gatwick str Lon ategies don to Scotland West London to Wales The division of rou tes for the F progra elixstowe to Midlands mme of route strategies on t he Solent to Midlands Strategic Road Network M25 to Solent (A3 and M3) Kent Corridor to M25 (M2 and M20) South Coast Central Birmingham to Exeter A1 South West Peninsula London to Leeds (East) East of England South Pennines A19 A69 North Pen Newccaastlstlee upon Tyne nines Carlisle A1 Sunderland Midlands to Wales and Gloucest M6 ershire North and East Midlands A66 A1(M) A595 South Midlands Middlesbrougugh A66 A174 A590 A19 A1 A64 A585 M6 York Irish S Lee ea M55 ds M65 M1 Preston M606 M621 A56 M62 A63 Kingston upon Hull M62 M61 M58 A1 M1 Liver Manchest A628 A180 North Sea pool er M18 M180 Grimsby M57 A616 A1(M) M53 M62 M60 Sheffield A556 M56 M6 A46 A55 A1 Lincoln A500 Stoke-on-Trent A38 M1 Nottingham -

Tackling High Risk Regional Roads Safer Roads Fund Full

Mobility • Safety • Economy • Environment Tackling High-Risk Regional Roads Safer Roads Fund 2017/2018 FO UND Dr Suzy Charman Road Safety Foundation October 2018 AT ION The Royal Automobile Club Foundation for Motoring Ltd is a transport policy and research organisation which explores the economic, mobility, safety and environmental issues relating to roads and their users. The Foundation publishes independent and authoritative research with which it promotes informed debate and advocates policy in the interest of the responsible motorist. RAC Foundation 89–91 Pall Mall London SW1Y 5HS Tel no: 020 7747 3445 www.racfoundation.org Registered Charity No. 1002705 October 2018 © Copyright Royal Automobile Club Foundation for Motoring Ltd Mobility • Safety • Economy • Environment Tackling High-Risk Regional Roads Safer Roads Fund 2017/2018 FO UND Dr Suzy Charman Road Safety Foundation October 2018 AT ION About the Road Safety Foundation The Road Safety Foundation is a UK charity advocating road casualty reduction through simultaneous action on all three components of the safe road system: roads, vehicles and behaviour. The charity has enabled work across each of these components and has published several reports which have provided the basis of new legislation, government policy or practice. For the last decade, the charity has focused on developing the Safe Systems approach, and in particular leading the establishment of the European Road Assessment Programme (EuroRAP) in the UK and, through EuroRAP, the global UK-based charity International Road Assessment Programme (iRAP). Since the inception of EuroRAP in 1999, the Foundation has been the UK member responsible for managing the programme in the UK (and, more recently, Ireland), ensuring that these countries provide a global model of what can be achieved. -

Columbus Bar Food Menu 210Mm

COLUMBUS BAR FOOD Holiday Inn Darlington A1 Scotch Corner A1 Scotch Corner Junction | A1/A66 nr Darlington | Richmond North Yorkshire | DL10 6NR | Tel: 01748 850 900 | Fax: 01748 825 417 [email protected] While you wait Mains Pizzas Baguettes Lemon & chilli marinated Kalamata olives £3.45 Chefs’ pie - Mash or triple cooked chips, buttered greens £11.25 Available from 12noon – 3am Served with salad & skin-on skinny fries (crisps between 10pm – 7am) 24 Crispy bubble n squeak cake, HP gravy £3.45 Chicken Rogan josh - Coconut basmati rice, £12.75 24 Margarita - Classic tomato base with mozzarella topping £9.75 Classic BLT, toasted bread, romaine lettuce, bacon, £7.95 plum tomatoes, mayo Sourdough, crusty bread, balsamic & extra virgin £3.45 mango chutney, house made coriander flatbread Spicy Meat Pizza - Tomato and herb base with chicken, £12.50 Tuscan sausage, salami, pepperoni, ham, jalapeno’s, Add chicken...£2.00 Salt n pepper calamari, chunky tartar £3.45 Classic Lasagne al forno - Garlic bread, green salad £12.50 chilli flakes and mozzarella Flat iron steak, caramelised onions, rocket, dijonaise £8.95 Slow cooked beef chilli, basmati rice, jalapenos, £12.95 24 chive sour cream & nachos Veggie Supreme - Garlic base with sun kissed tomatoes, £10.50 Cheddar cheese & crunchy slaw savoury £7.95 24 sweetcorn, olives, fire roasted peppers, docelatte 24 Beer battered cod, triple cooked chips, mushy peas, £12.25 and mozzarella Honey roast ham, salami, tomato, mozzarella & pesto £8.75 Starters chunky tartar sauce, charred lemon All on thin -

Adapting Marriage: Law Versus Custom in Early Modern English

ADAPTING MARRIAGE: LAW VERSUS CUSTOM IN EARLY MODERN ENGLISH PLAYS by Jennifer Dawson Kraemer APPROVED BY SUPERVISORY COMMITTEE: ___________________________________________ Dr. Jessica C. Murphy, Chair ___________________________________________ Dr. Pamela Gossin ___________________________________________ Dr. Adrienne L. McLean ___________________________________________ Dr. Gerald L. Soliday Copyright 2018 Jennifer Dawson Kraemer All Rights Reserved For my family whose patience and belief in me allowed me to finish this dissertation. There were many appointments, nutritious dinners, and special outings foregone over the course of graduate school and dissertation writing, but you all understood and supported me nonetheless. ADAPTING MARRIAGE: LAW VERSUS CUSTOM IN EARLY MODERN ENGLISH PLAYS by JENNIFER DAWSON KRAEMER, BA, MA DISSERTATION Presented to the Faculty of The University of Texas at Dallas in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN HUMANITIES – STUDIES IN LITERATURE MAJOR IN STUDIES IN LITERATURE THE UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS AT DALLAS August 2018 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The inspiration for this dissertation can best be described as a kind of coalescence of droplets rather than a seed that was planted and grew. For these droplets to fuse at all instead of evaporating, I have the members of my dissertation committee to thank. Dr. Gerald L. Soliday first introduced me to exploring literature through the lens of historical context while I was pursuing my master’s degree. To Dr. Adrienne McLean, I am immensely grateful for her willingness to help supervise a non-traditional adaptation project. Dr. Pamela Gossin has been a trusted advisor for a long time, and her vast and diverse range of academic interests inspired me to attempt this fusion of adaptation theory and New Historicism. -

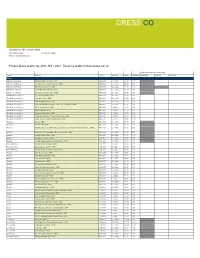

Cress Christmas 2021 Order Form.Xlsx

CRESS CO Christmas 2021 order form Account name: Contact name: Email confirmation to: Please place orders by 30th JULY 2021 Email to [email protected] Delivery from week commencing : range productcode case size price unit price14th Sept 12th Oct 22nd Nov Bakery Melrose and Morgan Christmas Iced Loaf Cake - NEWMMM/001 6 x 650g 65.70 10.95 Melrose and Morgan Gingerbread snow flakes & stars - NEWMMM/002 12 x 110g 48.00 4.00 Melrose and Morgan Mince Pies (pack of 6) - NEWMMM/004 12 x 300g 67.20 5.60 Melrose and Morgan Coffee dusted Hazelnuts - NEWMMM/005 12 x 125g 77.00* 6.42* Melrose and Morgan Chocolate candied Ginger - NEWMMM/006 12 x 125g 77.00* 6.42* The Buxton Pudding Co Fig, Cherry & Sherry - NEWBUX/050 14 x 165g 41.70 2.98 The Buxton Pudding Co Tipsy Fruit Cake - NEWBUX/051 14 x 165g 41.70 2.98 The Buxton Pudding Co Plum & Apple Brandy - NEWBUX/052 14 x 165g 41.70 2.98 The Buxton Pudding Co Fruit Cake Mixed Case Small ( Mix of all 3 flavours ) - NEWBUX/053 14 x 165g 41.70 2.98 The Buxton Pudding Co Fig, Cherry & Sherry - NEWBUX/054 7 x 500g 61.33 8.76 The Buxton Pudding Co Tipsy Fruitcake - NEWBUX/055 7 x 520g 61.33 8.76 The Buxton Pudding Co Plum & Apple Brandy - NEWBUX/056 7 x 570g 61.33 8.76 The Buxton Pudding Co Jewelled and Gilded 4” Round Fruit Cake - NEWBUX/059 6 x 550g 65.00 10.83 The Buxton Pudding Co Iced 4” Round Tipsy Christmas Cake - NEWBUX/060 6 x 550g 65.00 10.83 Wicklein Allerlei - NEWWIC/001 20 x 300g 47.78 2.39 Wicklein Pfeffernusse - NEWWIC/002 20 x 300g 54.73 2.74 Wicklein Milk Chocolate Coated Mini Elisen -

Eventful Experiences!

Eventful Experiences! S Along with our Taste Sensations and Roll Back the Years pages, we are excited to offer a wider range of Events than ever E before. We have handpicked several favourites to feature next to NEW group friendly event s, that we hope will capture your G imagination. This is only a selection of Events we can offer, please contact our Sales Team if you don’t see your favourite here. A K BEAMISH GREAT NORTH STEAM FAIR 3 DAYS from only £85 C Relive the golden days of steam at the 3 Days Half Board A Beamish Great North Steam Fair. With vintage apRil 2013 P vehicles, steam rollers, traction engines, Twin from £85.00 stationary engines, the magnificent colliery winding engine and guest appearances of Entrance T included fabulous machines. The museum and other Inclusions Beamish attractions including The Fairground, u 2 nights half board N u Home Farm and The Pit Village are open as Entrance into Beamish Village VINTAGE LOCOMOTIVES E usual for this Event. V E YORK CHOCOLATE FESTIVAL NEW 3 DAYS from only £59 R With York being the home to Rowntree and 3 Days Half Board Terry’s, The York Chocolate Festival could E apRil 2013 not be better placed! The history of the Twin from £59.00 confectionary giants still have a strong link to the M present day businesses in York. A programme Free full of chocolate dinners, workshops, tastings, Inclusions Event u M lectures, as well as demonstrations from the 2 nights half board region's premier chocolatiers await you.