Damon Salesa, University of Michigan (Not for Citation). 1 Princeton

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Echoes of Pacific War

ECHOES of Pacific War Edited by Deryck Scarr, Niel Gunson, Jennifer Terrell Echoes of Pacific War Edited by Deryck Scarr, Niel Gunson, Jennifer Terrell Papers from the 7th Tongan History Conference held in Canberra in January 1997 TARGET OCEANIA CANBERRA 1998 © Deryck Scarr, Niel Gunson, Jennifer Terrell 1998 This work is copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study, research, criticism or review as permitted under the Copyright Act, no part may be reproduced by any process without written permission. Book and cover design by Jennifer Terrell Printed by ANU Printing and Publishing Service ISBN 0-646-36000-0 Published by TARGET OCEANIA c/ o Division of Pacific and Asian History Research School of Pacific and Asian Studies Australian National University Canberra, ACT 0200, Australia Contents Maps and Figures v Fo reword ix Introduction xiii 1 Behind the battle lines: Tonga in World War II EUZABETHWOOD-EILEM 1 2 Changing values and changed psychology of Tongans during and since World War II 'I. F. HELU 26 3 Airplanes and saxaphones: post-war images in the visual and peiforming arts ADRIENNE L. KAEPPIER 38 4 Tonga and Australia since Wo rld War II GARETH GRAINGER 64 5 New behaviours and migration since Wo rld War II SIOSIUA F. POUVALU LAFITANI 76 6 The churches in Tonga since World War II JOHN GARRE'IT 87 7 Introduction and development of fa mily planning in Tonga 1958-1990 HENRY IVARATURE 99 8 Analysing the emergent mi ddle class - the 1990s KERRY JAMES 110 9 Changing interpretations of the kava ritual MEREDITH FILIHIA 127 10 How To ngan is a Tongan? Cultural authenticity revisited HELEN MORTON 149 Bibliograp hy 167 Index 173 Contributors 182 Maps Map 1: TheTonga Islands vii Map 2: Tongatapu 5 Map 3: Nuku'alofa 10 Figures Figure 1. -

Rotuman Educational Resource

Fäeag Rotuam Rotuman Language Educational Resource THE LORD'S PRAYER Ro’ạit Ne ‘Os Gagaja, Jisu Karisto ‘Otomis Ö’fāat täe ‘e lạgi, ‘Ou asa la ȧf‘ȧk la ma’ma’, ‘Ou Pure'aga la leum, ‘Ou rere la sok, fak ma ‘e lạgi, la tape’ ma ‘e rȧn te’. ‘Äe la nāam se ‘ạmisa, ‘e terạnit 'e ‘i, ta ‘etemis tē la ‘ā la tạu mar ma ‘Äe la fạu‘ạkia te’ ne ‘otomis sara, la fak ma ne ‘ạmis tape’ ma rē vạhia se iris ne sar ‘e ‘ạmisag. ma ‘Äe se hoa’ ‘ạmis se faksara; ‘Äe la sại‘ạkia ‘ạmis ‘e raksa’a, ko pure'aga, ma ne’ne’i, ma kolori, mou ma ke se ‘äeag, se av se ‘es gata’ag ne tore ‘Emen Rotuman Language 2 Educational Resource TABLE OF CONTENTS ROGROG NE ĀV TĀ HISTORY 4 ROGROG NE ROTUMA 'E 'ON TẠŪSA – Our history 4 'ON FUẠG NE AS TA ROTUMA – Meaning behind Rotuma 5 HẠITOHIẠG NE FUẠG FAK PUER NE HANUA – Chiefly system 6 HATAG NE FĀMORI – Population 7 ROTU – Religion 8 AGA MA GARUE'E ROTUMA – Lifestyle on the island 8 MAK A’PUMUẠ’ẠKI(T) – A treasured song 9 FŪ’ÅK NE HANUA GEOGRAPHY 10 ROTUMA 'E JAJ(A) NE FITI – Rotuma on the map of Fiji 10 JAJ(A) NE ITU ’ HIFU – Map of the seven districts 11 FÄEAG ROTUẠM TA LANGUAGE 12 'OU ‘EA’EA NE FÄEGA – Pronunciation Guide 12-13 'ON JĪPEAR NE FÄEGA – Notes on Spelling 14 MAF NE PUKU – The Rotuman Alphabet 14 MAF NE FIKA – Numbers 15 FÄEAG ‘ES’ AO - Useful words 16-18 'OU FÄEAG’ÅK NE 'ÄE – Introductions 19 UT NE FAMORI A'MOU LA' SIN – Commonly Frequented Places 20 HUẠL NE FḀU TA – Months of the year 21 AG FAK ROTUMA CULTURE 22 KATO’ AGA - Traditional ceremonies 22-23 MAMASA - Welcome Visitors and returnees 24 GARUE NE SI'U - Artefacts 25 TĒFUI – Traditional garland 26-28 MAKA - Dance 29 TĒLA'Ā - Food 30 HANUJU - Storytelling 31-32 3 ROGROG NE ĀV TĀ HISTORY Legend has it that Rotuma’s first inhabitants Consequently, the two religious groups originated from Samoa led by Raho, a chief, competed against each other in the efforts to followed by the arrival of Tongan settlers. -

(A) No Person Or Corporation May Publish Or Reproduce in Any Manner., Without the Consent of the Committee on Research And-Graduate

RULES ADOPTED BY THE BOARD OF REGENTS OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAII NOV 8 1955 WITH REGARD TO THE REPRODUCTION OF MASTERS THESES (a) No person or corporation may publish or reproduce in any manner., without the consent of the Committee on Research and-Graduate. Study, a. thesis which has been submitted to the University in partial fulfillment of the require ments for an advanced degree, {b ) No individual or corporation or other organization may publish quota tions or excerpts from a graduate thesis without the consent of the author and of the Committee on Research and Graduate Study. UNIVERSITY OF HAWAII LIBRARY A STUDY CF SOCIO-ECONOMIC VALUES OF SAMOAN INTERMEDIATE u SCHOOL STUDENTS IN HAWAII A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAII IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT CF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS JUNE 1956 Susan E. Hirsh Hawn. CB 5 H3 n o .345 co°“5 1 TABLE OP CONTENTS LIST GF TABUS ............................... iv CHAPTER. I. STATEMENT CP THE PROBLEM ........ 1 Introduction •••••••••••.•••••• 1 Th« Problem •••.••••••••••••••• 3 Methodology . »*••*«* i «#*•**• t * » 5 II. CONTEMPORARY SAMOA* THE CULTURE CP ORIGIN........ 10 Socio-Economic Structure 12 Soeic-Eoonosdo Chong« ••••••«.#•••«• 15 Socio-Economic Values? •••••••••••».. 17 Conclusions 18 U I . TBE SAIOAIS IN HAWAII» PEARL HARBOR AND LAXE . 20 Peerl Harbor 21 Lala ......... 24 Sumaary 28 IV. SELECTED BACKGROUND CHARACTERISTICS OP SAMOAN AND NON-SAMOAN INTERMEDIATE SCHOOL STUDENTS IN HAWAII . 29 Location of Residences of Students ••••••• -

Vol. 17 No. 3 Pacific Studies

PACIFIC STUDIES A multidisciplinary journal devoted to the study of the peoples of the Pacific Islands SEPTEMBER 1994 Anthropology Archaeology Art History Economics Ethnomusicology Folklore Geography History Sociolinguistics Political Science Sociology PUBLISHED BY T HE INSTITUTE FOR POLYNESIAN STUDIES BRIGHAM YOUNG UNIVERSITY--HAWAII IN ASSOCIATION WITH THE POLYNESIAN CULTURAL CENTER EDITORIAL BOARD Paul Alan Cox Brigham Young University Roger Green University of Auckland Renée Heyum University of Hawaii Francis X. Hezel, S.J. Micronesian Seminar Rubellite Johnson University of Hawaii Adrienne Kaeppler Smithsonian Institution Robert Kiste University of Hawaii Robert Langdon Australian National University Stephen Levine Victoria University Barrie Macdonald Massey University Cluny Macpherson University of Auckland Leonard Mason University of Hawaii Malama Meleisea University of Auckland Norman Meller University of Hawaii Richard M. Moyle University of Auckland Colin Newbury Oxford University Douglas Oliver University of Hawaii Margaret Orbell Canterbury University Nancy Pollock Victoria University Karl Rensch Australian National University Bradd Shore Emory University Yosihiko Sinoto Bishop Museum William Tagupa Honolulu, Hawaii Francisco Orrego Vicuña Universidad de Chile Edward Wolfers University of Wollongong Articles and reviews in Pacific Studies are abstracted or indexed in Sociolog- ical Abstracts, Linguistics and Language Behavior Abstracts, America: His- tory and Life, Historical Abstracts, Abstracts in Anthropology, Anthropo- -

Science Briefing March 14Th, 2019

Science Briefing March 14th, 2019 Prof. Annette Lee (St. Cloud State University) The Native American Sky Mr. Kalepa Baybayan (Imiloa Astronomy Center of Hawai’i) Dr. Laurie Rousseau-Nepton (Canada-France-Hawaii Telescope) Facilitator: Dr. Christopher Britt Outline of this Science Briefing 1. Prof. Annette Lee, St. Cloud State University; University of Southern Queensland As It is above, it is below: Kapemni doorways in the night sky 2. Kālepa Baybayan, Imiloa Astronomy Center of Hawai’i He Lani Ko Luna, A Sky Above: In Losing the Sight of Land You Discover the Stars 3. Dr. Laurie Rousseau-Nepton, Canada-France-Hawaii Telescope A Time When Everyone Was an Astronomer 4. Resources Brief presentation of resources 5. Q&A 2 As It is above; it is below Kapemni doorways in the night sky Painting by A. Lee, A. Lee, © 2014 Painting by Dept. Physics and Astronomy Annette S. Lee Thurs., Mar. 14, 2019 Centre for Astrophysics 3 NASA’s Universe of Learning Science Briefing The Native American Sky Star Map by A. Lee, W. Wilson, C. Gawboy © 2012 Star Map by A. Lee © 2012 4 5 Star Map by A. Lee, W. Wilson, W. Buck © 2016 Star Map by A. Lee © 2016 One Sky Many Astronomies – Permanent Exhibit Canada Science & Technology Museum, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada 6 7 8 9 Kepler'ssupernova remnant, SN 1604 10 STAR/SPIRIT WORLD Kapemni As it is above… it is below. A Mirroring EARTH/MATERIAL WORLD 11 Tu Blue (Spirit) Woman Birth Woman Wiçakiyuha¡i Stretcher & Mourners Close up, Painting by A. Lee, © 2014 12 Doorway 13 Star Map by A. -

Tātou O Tagata Folau. Pacific Development Through Learning Traditional Voyaging on the Waka Hourua, Haunui

Tātou o tagata folau. Pacific development through learning traditional voyaging on the waka hourua, Haunui. Raewynne Nātia Tucker 2020 School of Social Sciences and Public Policy, Faculty of Culture and Society A thesis submitted to Auckland University of Technology in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Philosophy Table of Contents Table of Contents .......................................................................................................... i Abstract ........................................................................................................................ v List of Figures .............................................................................................................. vi List of Tables ............................................................................................................... vii List of Appendices ...................................................................................................... viii List of Abbreviations .................................................................................................... ix Glossary ....................................................................................................................... x Attestation of Authorship ............................................................................................. xiii Acknowledgements ..................................................................................................... xiv Chapter 1: Introduction ................................................................................................ -

A History of the Pacific Islands

A HISTORY OF THE PACIFIC ISLANDS I. C. Campbell A HISTORY OF THE PACIFIC ISLANDS Thi s One l N8FG-03S-LXLD A History of the Pacific Islands I. C. CAMPBELL University of California Press Berkeley • Los Angeles Copyrighted material © 1989 I. C. Campbell Published in 1989 in the United States of America by the University of California Press Berkeley and Los Angeles All rights reserved. Apart from any fair use for the purposes of private study, research, criticism or review, no part whatsoever may by reproduced by any process without the express written permission of the author and the University of California Press. Library of Congress Cataloguing-in-Publication Data Campbell, LC. (Ian C), 1947- A history of the Pacific Islands / LC. Campbell, p. cm. "First published in 1989 by the University of Canterbury Press, Christchurch, New Zealand" — T.p. verso. Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 0-520-06900-5 (alk. paper). — ISBN 0-520-06901-3 (pbk. alk. paper) 1. Oceania — History. I. Title DU28.3.C35 1990 990 — dc20 89-5235 CIP Typographic design: The Caxton Press, Christchurch, New Zealand Cover design: Max Hailstone Cartographer: Tony Shatford Printed by: Kyodo-Shing Loong Singapore C opy righted m ateri al 1 CONTENTS List of Maps 6 List of Tables 6 A Note on Orthography and Pronunciation 7 Preface. 1 Chapter One: The Original Inhabitants 13 Chapter Two: Austronesian Colonization 28 Chapter Three: Polynesia: the Age of European Discovery 40 Chapter Four: Polynesia: Trade and Social Change 57 Chapter Five: Polynesia: Missionaries and Kingdoms -

Seacare Authority Exemption

EXEMPTION 1—SCHEDULE 1 Official IMO Year of Ship Name Length Type Number Number Completion 1 GIANT LEAP 861091 13.30 2013 Yacht 1209 856291 35.11 1996 Barge 2 DREAM 860926 11.97 2007 Catamaran 2 ITCHY FEET 862427 12.58 2019 Catamaran 2 LITTLE MISSES 862893 11.55 2000 857725 30.75 1988 Passenger vessel 2001 852712 8702783 30.45 1986 Ferry 2ABREAST 859329 10.00 1990 Catamaran Pleasure Yacht 2GETHER II 859399 13.10 2008 Catamaran Pleasure Yacht 2-KAN 853537 16.10 1989 Launch 2ND HOME 856480 10.90 1996 Launch 2XS 859949 14.25 2002 Catamaran 34 SOUTH 857212 24.33 2002 Fishing 35 TONNER 861075 9714135 32.50 2014 Barge 38 SOUTH 861432 11.55 1999 Catamaran 55 NORD 860974 14.24 1990 Pleasure craft 79 199188 9.54 1935 Yacht 82 YACHT 860131 26.00 2004 Motor Yacht 83 862656 52.50 1999 Work Boat 84 862655 52.50 2000 Work Boat A BIT OF ATTITUDE 859982 16.20 2010 Yacht A COCONUT 862582 13.10 1988 Yacht A L ROBB 859526 23.95 2010 Ferry A MORNING SONG 862292 13.09 2003 Pleasure craft A P RECOVERY 857439 51.50 1977 Crane/derrick barge A QUOLL 856542 11.00 1998 Yacht A ROOM WITH A VIEW 855032 16.02 1994 Pleasure A SOJOURN 861968 15.32 2008 Pleasure craft A VOS SANTE 858856 13.00 2003 Catamaran Pleasure Yacht A Y BALAMARA 343939 9.91 1969 Yacht A.L.S.T. JAMAEKA PEARL 854831 15.24 1972 Yacht A.M.S. 1808 862294 54.86 2018 Barge A.M.S. -

The Conflict Between Traditional Knowledge and Modernity in the Navigation of Polynesia

Journal of World Anthropology: Occasional Papers: Volume III, Number 2 48 “When earth and sky almost meet”: The Conflict between Traditional Knowledge and Modernity in Polynesian Navigation. Luke Strongman1 Abstract This paper provides an account of the differing ontologies of Polynesian and European navigation techniques in the Pacific. The subject of conflict between traditional knowledge and modernity is examined from nine points of view: The cultural problematics of textual representation, historical differences between European and Polynesian navigation; voyages of re-discovery and re-creation: Lewis and Finney; How the Polynesians navigated in the Pacific; a European history of Polynesian navigation accounts from early encounters; “Earth and Sky almost meet”: Polynesian literary views of recovered knowledge; lost knowledge in cultural exchanges – the parallax view; contemporary views and lost complexities. Introduction Polynesians descended from kinship groups in south-east Asia discovered new islands in the Pacific in the Holocene period, up to 5000 calendar years before the present day. The European voyages of discovery in the Pacific from the eighteenth century, in the Anthropocene era, brought Polynesian and European cultures together, resulting in exchanges that threw their cross-cultural differences into relief. As Bernard Smith suggests: “The scientific examination of the Pacific, by its very nature, depended on the level reached by the art of navigation” (Smith 1985:2). Two very different cultural systems, with different navigational practices, began to interact. 1 The Open Polytechnic of New Zealand Journal of World Anthropology: Occasional Papers: Volume III, Number 2 49 Their varied cultural ontologies were based on different views of society, science, religion, history, narrative, and beliefs about the world. -

June Program Guide

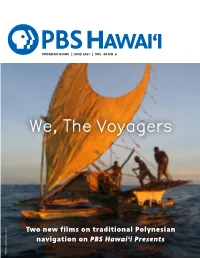

PROGRAM GUIDE | JUNE 2021 | VOL. 40 NO. 6 Two new films on traditional Polynesian navigation on PBS Hawai‘i Presents Wade Fairley, copyright Vaka Taumako Project Taumako copyright Vaka Fairley, Wade A Long Story That Informed, Influenced STATEWIDE BOARD OF DIRECTORS and Inspired Chair The show’s eloquent description Joanne Lo Grimes nearly says it all… Vice Chair Long Story Short with Leslie Wilcox Jason Haruki features engaging conversations with Secretary some of the most intriguing people in Joy Miura Koerte Hawai‘i and across the world. Guests Treasurer share personal stories, experiences Kent Tsukamoto and values that have helped shape who they are. Muriel Anderson What it does not express is the As we continue to tell stories of Susan Bendon magical presence Leslie brought to Hawai‘i’s rich history, our content Jodi Endo Chai will mirror and reflect our diverse James E. Duffy Jr. each conversation and the priceless communities, past, present and Matthew Emerson collection of diverse voices and Jason Fujimoto untold stories she captured over the future. We are in the process of AJ Halagao years. Former guest Hoala Greevy, redefining some of our current Ian Kitajima Founder and CEO of Paubox, Inc., programs like Nā Mele: Traditions in Noelani Kalipi may have said it best, “Leslie was Hawaiian Song and INSIGHTS ON PBS Kamani Kuala‘au HAWAI‘I, and soon we will announce Theresia McMurdo brilliant to bring all of these pieces Bettina Mehnert of Hawai‘i history together to live the name and concept of a new series. Ryan Kaipo Nobriga forever in one amazing library. -

IAOS International Association for Obsidian Studies Bulletin

IAOS International Association for Obsidian Studies Bulletin Number 44 Winter 2011 CONTENTS International Association for Obsidian Studies News and Information ………………………… 1 President Tristan Carter Notes from the President ……………….………. 2 Past-President Anastasia Steffen Obituary: Roger C. Green………………………. 4 Secretary-Treasurer S. Colby Phillips IAOS Elections: Candidate Statements…..….…. 6 Bulletin Editor Carolyn Dillian News and Notes……………………………….... 8 Webmaster Craig Skinner Iridescent Obsidian from Tenerife………...……..9 Instructions for Authors …..…………………… 12 Web Site: http://www.peak.org/obsidian About the IAOS………………………………… 13 Membership Application ……………………….. 14 NEWS AND INFORMATION CONSIDER PUBLISHING IN THE IAOS Annual Meeting IAOS BULLETIN The annual meeting of the IAOS will be The Bulletin is a twice-yearly publication that held at the 2011 Society for American reaches a wide audience in the obsidian community. Archaeology meetings in Sacramento, Please review your research notes and consider California. The IAOS meeting will be submitting an article, research update, news, or lab Friday April 1 at 3.30-5pm. Please see your report for publication in the IAOS Bulletin. Articles SAA program for meeting location. and inquiries can be sent to [email protected] Thank you for your help and support! IAOS Elections We will hold electronic elections for President-Elect and Secretary-Treasurer in preparation for the 2011 IAOS Annual Meeting in Sacramento, CA. Candidate statements can be found on pages 6-7 of this IAOS Bulletin. Please email your vote to the current IAOS President, Tristan Carter at [email protected] with “IAOS elections” in the subject line. NOTES FROM THE PRESIDENT Greetings once again, this time from the European Association of Archaeology, snowy tail-end of term, as we approach the together with the 2012 bi-annual conference holiday season and that small window of post- of the International Symposium of teaching research time before unadulterated Archaeometry to be held in Liège, Belgium. -

The Canoe Is the People LEARNER's TEXT

The Canoe Is The People LEARNER’S TEXT United Nations Local and Indigenous Educational, Scientific and Knowledge Systems Cultural Organization Learnerstxtfinal_C5.indd 1 14/11/2013 11:28 The Canoe Is the People educational Resource Pack: Learner’s Text The Resource Pack also includes: Teacher’s Manual, CD–ROM and Poster. Produced by the Local and Indigenous Knowledge Systems (LINKS) Programme, UNESCO www.unesco.org/links Published in 2013 by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization 7, place de Fontenoy, 75352 Paris 07 SP, France ©2013 UNESCO All rights reserved The designations employed and the presentation of material throughout this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of UNESCO concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The ideas and opinions expressed in this publication are those of the authors; they are not necessarily those of UNESCO and do not commit the Organization. Coordinated by Douglas Nakashima, Head, LINKS Programme, UNESCO Author Gillian O’Connell Printed by UNESCO Printed in France Contact: Douglas Nakashima LINKS Programme UNESCO [email protected] 2 The Canoe Is the People: Indigenous Navigation in the Pacific Learnerstxtfinal_C5.indd 2 14/11/2013 11:28 contents learner’s SECTIONTEXT 3 The Canoe Is the People: Indigenous Navigation in the Pacific Learnerstxtfinal_C5.indd 3 14/11/2013 11:28 Acknowledgements The Canoe Is the People Resource Pack has benefited from the collaborative efforts of a large number of people and institutions who have each contributed to shaping the final product.