Message-Of-The-Gita.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Mahabharata Twenty-Five Years Later

THE MAHABHARATA TWENTy-Five YEARS LATER Peter Brook in conversation with Jonathan Kalb t age eighty-five, Peter Brook does all he can to avoid interviews. He has no interest in his own legend, and as for his theatrical ideas, he has said it all before, in his autobiography (Threads of Time), in his other books (The AEmpty Space, The Shifting Point), and in the body of influential productions that established him as one of the giants of twentieth-century theatre. At the request of a common friend, he nevertheless kindly agreed to speak to me on the subject of his magnum opus, The Mahabharata—a focus of the book I was writing at the time (Great Lengths: Seven Marathon Plays from Three Decades, forthcoming). Brook was in New York rehearsing his adaptation of Mozart’s The Magic Flute at Lincoln Center and accompanying the Theatre for a New Audience presentation of Love is My Sin, his staging of Shakespeare sonnets. Although he announced in 2008 that he was giving up day-to-day operation of his theatre in Paris, Bouffes du Nord, he has been notably active. Among his other recent projects have been: Fragments, a program of five short pieces by Samuel Beckett; Athol Fugard’sSizwe Banzi is Dead; The Grand Inquisitor, adapted from Dostoyevsky; and Tierno Bokar, a parable about tolerance and fundamentalism rooted in a spiritual dispute among Sufis. The Mahabharata was Brook’s eleven-hour stage adaptation of the massive, epic cor- nerstone of Hindu literature, religion and culture, originally produced in French in 1985 and performed in English for a 1987 world tour that included the Brooklyn Academy of Music’s Majestic Theatre (now The Harvey). -

Bhagawan Sri Sathya Sai Baba

Om Sri Sai Ram BHAGAVAT GITA VAHINI By Bhagawan Sri Sathya Sai Baba Greetings Bhagawan Sri Sathya Sai Baba is the Sanathana Sarathi, the timeless charioteer, who communicated the Geetha Sastra to Adithya and helped Manu and king Ikshwaku to know it; He was the charioteer of Arjuna during the great battle between good and evil fought out at Kurukshetra. When the rider, Arjuna, was overcome with grief at the prospect of the fight, Krishna instructed him in the science of recognising one's oneness with all, and removed the grief and the fear. He is the charioteer even now, for every one of us; let me greet you as a fellow-sufferer and a fellow-disciple. We have but to recognise Him and accept Him in that role, holding the reins of discrimination and flourishing the whip of detachment, to direct the horses of the senses along the path of Sathya, asphalted by Dharma and illumined by Prema towards the goal of Shanthi. Arjuna accepted Him in that role; let us do likewise. When worldly attachment hinders the path of duty, when ambition blinds the eyes of sympathy, when hate shuts out the call of love, let us listen to the Geetha. He teaches us from the chariot whereon He is installed. Then He showers His grace, His vision and His power, and we are made heroes fit to fight and win. This precious book is not a commentary or summary of the Geetha that was taught on the field of Kurukshetra. We need not learn any new language or read any old text to imbibe the lesson that the Lord is eager to teach us now, for victory in the battle we are now waging. -

An Understanding of Maya: the Philosophies of Sankara, Ramanuja and Madhva

An understanding of Maya: The philosophies of Sankara, Ramanuja and Madhva Department of Religion studies Theology University of Pretoria By: John Whitehead 12083802 Supervisor: Dr M Sukdaven 2019 Declaration Declaration of Plagiarism 1. I understand what plagiarism means and I am aware of the university’s policy in this regard. 2. I declare that this Dissertation is my own work. 3. I did not make use of another student’s previous work and I submit this as my own words. 4. I did not allow anyone to copy this work with the intention of presenting it as their own work. I, John Derrick Whitehead hereby declare that the following Dissertation is my own work and that I duly recognized and listed all sources for this study. Date: 3 December 2019 Student number: u12083802 __________________________ 2 Foreword I started my MTh and was unsure of a topic to cover. I knew that Hinduism was the religion I was interested in. Dr. Sukdaven suggested that I embark on the study of the concept of Maya. Although this concept provided a challenge for me and my faith, I wish to thank Dr. Sukdaven for giving me the opportunity to cover such a deep philosophical concept in Hinduism. This concept Maya is deeper than one expects and has broaden and enlightened my mind. Even though this was a difficult theme to cover it did however, give me a clearer understanding of how the world is seen in Hinduism. 3 List of Abbreviations AD Anno Domini BC Before Christ BCE Before Common Era BS Brahmasutra Upanishad BSB Brahmasutra Upanishad with commentary of Sankara BU Brhadaranyaka Upanishad with commentary of Sankara CE Common Era EW Emperical World GB Gitabhasya of Shankara GK Gaudapada Karikas Rg Rig Veda SBH Sribhasya of Ramanuja Svet. -

Chapter Iv Data Analysis

CHAPTER IV DATA ANALYSIS Ramayana and Mahabharata are Wiracarita, the heroic stories which are well – known from one generation to another. These two great epics are originally written in Sanskrit. The author of Ramayana is Walmiki, and the author of Mahabharata is Bhagawan Wyasa. Ramayana and Mahabharata have been translated into various languages. In Indonesia, these two great epics have been retold in various versions such as Wayang kulit performance, dance, book, novel, and comic. For this research, the writer chooses the Mahabharata novel by Nyoman. S. Pendit. With the focus of the research on the heroic journey of Arjuna in this novel. In this chapter, the writer would like to answer and to analyze three problem formulations of this research. First, the writer would like to retell Arjuna‟s journey based on the twenty parts selected in the Mahabharata novel. After that, as the second problem formulation, the writer would like to compare to what extent the journey of Arjuna on the twenty parts selected in the Mahabharata novel fulfills the criteria of the Hero‟s Journey theory proposed by Joseph Campbell. The Hero‟s Journey theory itself consists of seventeen stages divided into three big stages: Departure – Initiation – Return. It can be seen from the journey of Arjuna in the Mahabharata novel by Nyoman. S. Pendit. After going through the several archetypal journey process framed in the Hero‟s Journey theory, Arjuna gets or shows the life virtues in himself. Therefore, as the third problem formulation, the 34 writer would like to mention what kind of life virtues showed by Arjuna on the twenty parts selected in the Mahabharata novel. -

2. a Superhit Goddess

Ganesh, lord of auspicious beginnings and father of goddess Santoshi Ma. A Superhit Goddess Jai Santoshi Maa and Caste Hierarchy in Indian Films Part One Philip Lutgendorf “Audiences were showering coins, perennials of its vast output, yet they quarter of national cinematic output) flower petals and rice at the screen constitute one of the least-studied enjoys the largest audience in appreciation of the film. They aspects of this comparatively under- throughout the Indian subcontinent entered the cinema barefoot and set studied cinema. Indeed, I will venture and beyond. Sholay (“Flames”) and up a small temple outside…. In that for scholars and critics, Deewar (“The Wall”), were both Bandra, where mythological films mythologicals have generally been heavily-promoted “multi-starrers” aren’t shown, it ran for fifty weeks. It “hard to see.” Yet DeMille’s words belonging to the then-dominant genre was a miracle”. —Anita Guha, also belie the fact that most sometimes referred to as the masala (actress who played goddess mythologicals—like most commercial (“spicy”) film: a multi-course cinematic Santoshi Ma; cited in Kabir films of any genre—flop at the box banquet incorporating suspenseful office. The comparatively few that drama, romance, comedy, violent 2001:115). have enjoyed remarkable and action sequences, and song and Genre, Film & Phenomenon sustained acclaim hence merit study dance. Both were expensive and Cecil B. DeMille’s famously both as religious expressions and as slickly made by the standards of the cynical adage, “God is box office,” successful examples of popular art and industry, and both featured Amitabh may be applied to Indian popular entertainment. -

Prabhat Prakashan (In English)

S.No ISBN Title Author MRP Lang. Pages Year Stock Binding 1 9789352664634 Kaka Ke Thahake Kaka Hathrasi 300.00 Hindi 128 2021 10 Hardcover 2 9789352664627 Kaka Ke Golgappe Kaka Hathrasi 450.00 Hindi 184 2021 10 Hardcover 3 9789386870803 Hindu Dharma Mein Vaigyanik Manyatayen K.V. Singh 400.00 Hindi 184 2021 10 Hardcover 4 9789390366842 Ahilyabai (& udaykiran) Vrindavan Lal Verma 700.00 Hindi 352 2021 10 Hardcover 5 9789352669394 Sudha Murty Ki Lokpriya Kahaniyan Sudha Murty 350.00 Hindi 176 2021 10 Hardcover 6 9788173150500 Amarbel Vrindavan Lal Verma 400.00 Hindi 200 2021 10 Hardcover 7 9788173150999 Shreshtha Hasya Vyangya Ekanki Kaka Hatharasi 450.00 Hindi 224 2021 10 Hardcover 8 9789389982664 Mera Desh Badal Raha Hai Dr. A.P.J. Abdul Kalam 500.00 Hindi 224 2021 10 Hardcover 9 9789389982329 Netaji Subhash Ki Rahasyamaya Kahani Kingshuk Nag 350.00 Hindi 176 2021 10 Hardcover 10 9789389982022 Utho! Jago! Aage Barho Sandip Kumar Salunkhe 400.00 Hindi 160 2021 10 Hardcover 11 9789389982718 Champaran Andolan 1917 Ashutosh Partheshwar 400.00 Hindi 184 2021 10 Hardcover 12 9789389982916 Ramayan Ki Kahani, Vigyan Ki Zubani Saroj Bala 400.00 Hindi 206 2021 10 Hardcover 13 9789389982688 Vidyarthiyon Mein Avishkarak Soch Lakshman Prasad 400.00 Hindi 192 2021 10 Hardcover 14 9789390101757 Zimmedari (Responsibility) P.K. Arya 500.00 Hindi 240 2021 10 Hardcover 15 9789389982305 Samaya Prabandhan (Time Management) P.K. Arya 500.00 Hindi 232 2021 10 Hardcover 16 9789389982312 Smaran Shakti (Memory Power) P.K. Arya 400.00 Hindi 216 2021 10 Hardcover 17 9789389982695 Jannayak Atalji (Sampoorn Jeevani) Kingshuk Nag 350.00 Hindi 168 2021 10 Hardcover 18 9789389982671 Positive Thinking Napoleon Hill ; Michael J. -

Pendidikan Siswa/I

EDISI REVISI 2018 Pendidikan Agama Hindu dan Budi Pekerti Pendidikan Buku pelajaran pendidikan agama Hindu untuk siswa/i tingkat Sekolah Dasar ini disusun sesuai dengan Kurikulum 2013, agar siswa/i aktif dalam proses pembelajaran. Buku ini dilengkapi dengan Agama Hindu kegiatan-kegiatan seperti, berpendapat, kreativitasku, aktivitasku, diskusi dengan orang tua, diskusi di kelas, bermain huruf, teka-teki silang, menceritakan pengalaman, demontrasi dan latih kognitif. Semua kegiatan tersebut bertujuan membantu siswa/i memahami dan mengaplikasikan ajaran agama Hindu dan Budi Pekerti dalam kehidupan. Buku ini dilengkapi glosarium dan ilustrasi guna memotivasi siswa/i gemar membaca, Kelas III SD • menumbuhkan rasa cinta melalui ajaran Tri Parartha, memahami ajaran Hindu melalui tokoh-tokoh dalam Mahābhārata, mengenal ajaran Daivi dan Asuri Sampad dalam Kitab Bhagavadgītā, mengenal nama-nama planet dalam tata surya Hindu serta mencintai budaya Hindu melalui materi Tari Profan dan Tari Sakral. Dengan buku agama Hindu ini, kami berharap siswa/i dapat belajar dengan mudah dalam memahami materi-materi pelajaran pendidikan agama Hindu, sehingga dapat menumbuhkan semangat dan kreativitas dalam meningkatkan Sraddha dan Bhakti siswa/i. Pendidikan Agama Hindu dan Budi Pekerti Agama Pendidikan ZONA 1 ZONA 2 ZONA 3 ZONA 4 ZONA 5 HET RpXX.XXX RpXX.XXX RpXX.XXX RpXX.XXX RpXX.XXX ISBN: SD 978-602-282-224-0 (jilid lengkap) 978-602-282-227-1 (jilid 3) KELAS III Hak Cipta © 2018 pada Kementerian Pendidikan dan Kebudayaan Dilindungi Undang-Undang Disklaimer: Buku ini merupakan buku siswa yang dipersiapkan Pemerintah dalam rangka implementasi Kurikulum 2013. Buku siswa ini disusun dan ditelaah oleh berbagai pihak di bawah koordinasi Kementerian Pendidikan dan Kebudayaan, dan dipergunakan dalam tahap awal penerapan Kurikulum 2013. -

The Mahabharata

VivekaVani - Voice of Vivekananda THE MAHABHARATA (Delivered by Swami Vivekananda at the Shakespeare Club, Pasadena, California, February 1, 1900) The other epic about which I am going to speak to you this evening, is called the Mahâbhârata. It contains the story of a race descended from King Bharata, who was the son of Dushyanta and Shakuntalâ. Mahâ means great, and Bhârata means the descendants of Bharata, from whom India has derived its name, Bhârata. Mahabharata means Great India, or the story of the great descendants of Bharata. The scene of this epic is the ancient kingdom of the Kurus, and the story is based on the great war which took place between the Kurus and the Panchâlas. So the region of the quarrel is not very big. This epic is the most popular one in India; and it exercises the same authority in India as Homer's poems did over the Greeks. As ages went on, more and more matter was added to it, until it has become a huge book of about a hundred thousand couplets. All sorts of tales, legends and myths, philosophical treatises, scraps of history, and various discussions have been added to it from time to time, until it is a vast, gigantic mass of literature; and through it all runs the old, original story. The central story of the Mahabharata is of a war between two families of cousins, one family, called the Kauravas, the other the Pândavas — for the empire of India. The Aryans came into India in small companies. Gradually, these tribes began to extend, until, at last, they became the undisputed rulers of India. -

PDF Version of This Article

INDIA It's never too late... by Paramesh Krishnan Nair Afew years ago, a well-known Indian Reverso Inter-negative" process is prac¬ turned to powder, or after extraction of the film pioneer told me that of the forty tically unknown and all release copies are silver from the nitro-cellulose base, had odd films he had made he con¬ printed from the original negatives. As a been turned into bangles and ladies' sidered that only two or three were worth result, a large number of original negatives handbags. preserving in the National Film Archive of In¬ of highly successful films have been damag¬ One such film was Alam Ara (1 931 , in Hin¬ dia. This in a way reflects the attitude of most ed beyond repair due to indiscriminate di), the first Indian talkie, which is still not of our film-makers to archival preservation of duplication of positive prints, both 35mm traceable. When contacted two years before their films. and 16mm. his death, Ardeshir M. Irani, the maker of The average film-maker in India does not In India the cinema has never been ac¬ this film and the man who brought sound to believe that what he is doing is of any corded high priority. To the intelligentsia and Indian cinema, told us that he had kept some historical consequence, let alone of cultural educationists the cinema was something to reels of the film in his office at the Imperial interest. For him, as for his colleagues be looked down on with contempt and it was Studio (now Jyothi Studio). -

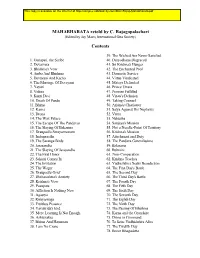

Rajaji-Mahabharata.Pdf

MAHABHARATA retold by C. Rajagopalachari (Edited by Jay Mazo, International Gita Society) Contents 39. The Wicked Are Never Satisfied 1. Ganapati, the Scribe 40. Duryodhana Disgraced 2. Devavrata 41. Sri Krishna's Hunger 3. Bhishma's Vow 42. The Enchanted Pool 4. Amba And Bhishma 43. Domestic Service 5. Devayani And Kacha 44. Virtue Vindicated 6. The Marriage Of Devayani 45. Matsya Defended 7. Yayati 46. Prince Uttara 8. Vidura 47. Promise Fulfilled 9. Kunti Devi 48. Virata's Delusion 10. Death Of Pandu 49. Taking Counsel 11. Bhima 50. Arjuna's Charioteer 12. Karna 51. Salya Against His Nephews 13. Drona 52. Vritra 14. The Wax Palace 53. Nahusha 15. The Escape Of The Pandavas 54. Sanjaya's Mission 16. The Slaying Of Bakasura 55. Not a Needle-Point Of Territory 17. Draupadi's Swayamvaram 56. Krishna's Mission 18. Indraprastha 57. Attachment and Duty 19. The Saranga Birds 58. The Pandava Generalissimo 20. Jarasandha 59. Balarama 21. The Slaying Of Jarasandha 60. Rukmini 22. The First Honor 61. Non-Cooperation 23. Sakuni Comes In 62. Krishna Teaches 24. The Invitation 63. Yudhishthira Seeks Benediction 25. The Wager 64. The First Day's Battle 26. Draupadi's Grief 65. The Second Day 27. Dhritarashtra's Anxiety 66. The Third Day's Battle 28. Krishna's Vow 67. The Fourth Day 29. Pasupata 68. The Fifth Day 30. Affliction Is Nothing New 69. The Sixth Day 31. Agastya 70. The Seventh Day 32. Rishyasringa 71. The Eighth Day 33. Fruitless Penance 72. The Ninth Day 34. Yavakrida's End 73. -

Summer Course Summer Course

SRI SATHYA SAI INSTITUTE OF HIGHER LEARNING (Deemed to be University) SUMMER COURSE in Indian Culture and Spirituality 2012 Summer Course in Indian Culture and Spirituality - 2012 Dedicated to our Beloved Master, Bhagawan Sri Sathya Sai Baba SRI SATHYA SAI INSTITUTE OF HIGHER LEARNING (Deemed to be University) SRI SATHYA SAI INSTITUTE OF HIGHER LEARNING (Deemed to be University) SUMMER COURSE in Indian Culture and Spirituality 8-10 June 2012 | Prasanthi Nilayam Copyright © 2012 by Sri Sathya Sai Institute of Higher Learning Vidyagiri, Prasanthi Nilayam – 515134, Anantapur District, Andhra Pradesh, India All Rights Reserved. The copyright and the rights of translation in any language are reserved by Sri Sathya Sai Institute of Higher Learning (Deemed to be University). No part, paragraph, passage, text, photograph or artwork of this book should be reproduced, transmitted or utilised - in original language or by translation - in any form or by means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or by any information, storage and retrieval system, except with prior permission, in writing from the Sri Sathya Sai Institute of Higher Learning, Vidyagiri, Prasanthi Nilayam - 515134, Anantapur District, Andhra Pradesh, India. First Edition: February 2013 Published by: Sri Sathya Sai Institute of Higher Learning www.sssihl.edu.in Printed at: Vagartha, # 149, 8th Cross, N R Colony, Bangalore – 560 019 +91 80 2242 7677 | [email protected] Preface The Sri Sathya Sai Institute of Higher Learning (SSSIHL) organized a Summer Course in Indian Culture and Spirituality from the 8th to 10th June 2012 at Prasanthi Nilayam, to mark the commencement of the new Academic Year. All the students and teachers of the Institute participated in this programme. -

The Bhagavadgita with the Sanatsujatiya and the Anugita

THE SACRED BOOKS OFTHEEAST Volume 8 SACRED BOOKS OF THE EAST EDITOR: F. Max Muller These volumes of the Sacred Books of the East Series include translations of all the most important works of the seven non Christian religions. These have exercised a profound innuence on the civilizations of the continent of Asia. The Vedic Brahmanic System claims 21 volumes, Buddhism 10, and Jainism 2;8 volumes comprise Sacred Books of the Parsees; 2 volumes represent Islam; and 6 the two main indigenous systems of China. thus placing the historical and comparative study of religions on a solid foundation. VOLUMES 1,15. TilE UPANISADS: in 2 Vols. F. Max Muller 2,14. THE SACRED LAWS OF THE AR VAS: in 2 vols. Georg Buhler 3,16,27,28,39,40. THE SACRED BOOKS OF CHINA: In 6 Vols. James Legge 4,23,31. The ZEND-AVESTA: in 3 Vols. James Darmesleler & L.H. Mills 5, 18,24,37,47. PHALVI TEXTS: in 5 Vall. E. W. West 6,9. THE QUR' AN: in 2 Vols. E. H. Palmer 7. The INSTITUTES OF VISNU: J.Jolly R. THE BHAGA VADGITAwith lhe Sanalsujllliya and the Anugilii: K.T. Telang 10. THE DHAMMAPADA: F. Max Muller SUTTA-NIPATA: V. Fausbiill 1 I. BUDDHIST SUTTAS: T.W. Rhys Davids 12,26,41,43,44. VINAYA TEXTS: in 3 Vols. T.W. Rhys Davids & II. Oldenberg 19. THE FO·SHO-HING·TSANG·KING: Samuel Beal 21. THE SADDHARMA-PUM>ARlKA or TilE LOTUS OF THE TRUE LAWS: /I. Kern 22,45. lAINA SUTRAS: in 2 Vols.