Analysis of the Independent Television Service's Documentaries, 2007–2016

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

KCET/PBS Socal Merger

CONTACT: Ariel Carpenter for KCETLink Media Group [email protected] or 747-201-5243 Jennifer Vides for PBS SoCal [email protected] or 310-237-4516 KCETLINK MEDIA GROUP AND PBS SOCAL ANNOUNCE MERGER New Organization Will Advance PBS Flagship Station in Southern California and Expand Original Content Creation and Innovation for Public Media Locally, and Across the Nation LOS ANGELES, April 25, 2018 – KCETLink Media Group (KCET), a leading national independent broadcast and digital network, and PBS SoCal (KOCE), the flagship PBS organization for Southern California, today announced an agreement to merge the two companies. The merger of equals creates a center for public media innovation and creativity that serves the more than 18 million people living in the Southern California region. The name of the new organization will be announced with the closing of the merger, which is expected to be completed in the first half of 2018. Establishing a powerful PBS flagship organization on the West Coast, the historic union of these two storied institutions creates the opportunity to produce more original programs for multiple channels and platforms that address the diverse community in Southern California and the nation, and innovate new community engagement experiences that educate, inform, entertain, and empower. KCET Board of Directors Chairman Dick Cook will serve as Board Chair, and PBS SoCal President and CEO Andrew Russell will be President and CEO of the new entity, which will be governed by a 32-person Board of Trustees composed of the 14 members from each of the boards of KCETLink and PBS SoCal, as well as four new Board appointees. -

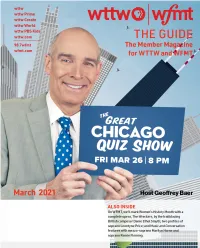

Geoffrey Baer, Who Each Friday Night Will Welcome Local Contestants Whose Knowledge of Trivia About Our City Will Be Put to the Test

From the President & CEO The Guide The Member Magazine Dear Member, for WTTW and WFMT This month, WTTW is excited to premiere a new series for Chicago trivia buffs and Renée Crown Public Media Center curious explorers alike. On March 26, join us for The Great Chicago Quiz Show hosted by 5400 North Saint Louis Avenue Chicago, Illinois 60625 WTTW’s Geoffrey Baer, who each Friday night will welcome local contestants whose knowledge of trivia about our city will be put to the test. And on premiere night and after, visit Main Switchboard (773) 583-5000 wttw.com/quiz where you can play along at home. Turn to Member and Viewer Services page 4 for a behind-the-scenes interview with Geoffrey and (773) 509-1111 x 6 producer Eddie Griffin. We’ll also mark Women’s History Month with American Websites wttw.com Masters profiles of novelist Flannery O’Connor and wfmt.com choreographer Twyla Tharp; a POV documentary, And She Could Be Next, that explores a defiant movement of women of Publisher color transforming politics; and Not Done: Women Remaking Anne Gleason America, tracing the last five years of women’s fight for Art Director Tom Peth equality. On wttw.com, other Women’s History Month subjects include Emily Taft Douglas, WTTW Contributors a pioneering female Illinois politician, actress, and wife of Senator Paul Douglas who served Julia Maish in the U.S. House of Representatives; the past and present of Chicago’s Women’s Park and Lisa Tipton WFMT Contributors Gardens, designed by a team of female architects and featuring a statue by Louise Bourgeois; Andrea Lamoreaux and restaurateur Niquenya Collins and her newly launched Afro-Caribbean restaurant and catering business, Cocoa Chili. -

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE CONTACT Mary Lugo 770

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE CONTACT Mary Lugo 770-623-8190 [email protected] Cara White 843-881-1480 [email protected] Voleine Amilcar, ITVS 415-356-8383 x244 [email protected] Pressroom for more information and/or downloadable images: http://www.itvs.org/pressroom/ Program companion website: http://www.pbs.org/catsofmirikitani Independent Lens: THE CATS OF MIRIKITANI TO HAVE ITS TELEVISION PREMIERE ON PBS, TUESDAY, MAY 8 AT 10:30 PM (Check Local Listings) “THE CATS OF MIRIKITANI is, quite simply, breathtaking — one of the most surprising and unshakable documentaries I can recall.” — New York Sun (San Francisco, CA) — “Make art not war” is Jimmy Mirikitani's motto. The 80-year-old artist was born in Sacramento, California, raised in Hiroshima, Japan, traveled to the U.S. and even cooked for artist Jackson Pollock. But by 2001, Mirikitani was homeless, living on the streets of New York City. As tourists and shoppers hurried past, Mirikitani sat alone on a windy corner in New York’s SoHo, drawing pictures of whimsical cats, bleak internment camps and the angry red flames of the atomic bomb. When local filmmaker Linda Hattendorf stopped to ask about his art, a friendship—detailed in THE CATS OF MIRIKITANI—began that changed both their lives. THE CATS OF MIRIKITANI will have its television premiere on the Emmy® Award-winning PBS series Independent Lens, hosted by Terrence Howard, on Tuesday, May 8 at 10:30 PM (check local listings). In sunshine, rain and snow, Hattendorf returned to document Mirikitani’s drawings, trying to decipher the stories behind them. -

November At-A-Glance *Join Us for a Fall Mystery Marathon on Thursday, November 26 and Friday, November 27

Original Concert Film Screening Fall Mystery Marathon— Series—page 9 Invitation—page 16 pages 17 & 18 Please visit wycc.org/schedule for the most current programming schedule. November at-a-glance *Join us for a Fall Mystery Marathon on Thursday, November 26 and Friday, November 27. Please check the listings for a full schedule. MONDAY TUESDAY WEDNESDAY THURSDAY* FRIDAY* SATURDAY SUNDAY 6:00 AM Classical Stretch Curious George Curious George The Cat in the Hat The Cat in the Hat 6:30 Body Electric Knows a Lot Knows a Lot About About That! That! (except 11/1) Wai Lana Yoga Ribert & Robert’s Mister Rogers’ 7:00 WonderWorld Neighborhood Sit and Be Fit Angelina Ballerina: Bob the Builder 7:30 The Next Steps Barney & Friends Sid the Science Kid 8:00 Odd Squad 8:30 Wild Kratts Arthur Zula Patrol 9:00 Sesame Street Sesame Street Sesame Street Wunderkind Cyberchase 9:30 Peg + Cat (starting 11/16) Little Amadeus 10:00 Dinosaur Train DragonflyTV Biz Kid$ Mid-American In the Americas with 10:30 Curious George Gardener David Yetman Bob the Builder Garden Smart Pritzker Military 11:00 Presents Victory Garden’s 11:30 Daniel Tiger’s Neighborhood (starting 11/16) EdibleFEAST PM P. Allen Smith’s Charlie Rose: 12:00 Super Why! Garden Home The Week Thomas & Friends This Old House Justice and Law 12:30 Weekly The Best of the Sewing with Nancy Well Read Quilting Arts The Beauty of The American Religion & Ethics 1:00 Joy of Painting Oil Painting Woodshop Newsweekly Wyland’s Art Studio Sew It All Between the Lines Fons & Porter’s Beads, Baubles, Hometime Closer to Truth 1:30 with Barry Kibrick Love of Quilting and Jewels Frank Clarke Simply Fit 2 Stitch Joseph Rosendo’s Knitting Daily The Donna The Woodwright’s Second Opinion 2:00 Painting Around the Travelscope Dewberry Show Shop World: China P. -

Discussion Guide

DISCUSSION GUIDE How does the simple act of planting trees lead to winning the Nobel Peace Prize? Ask Wangari Maathai of Kenya. In 1977, she suggested rural women plant trees to address problems stemming from a degraded environment. Under her leadership, their tree-planting grew into a nationwide movement to safeguard the environment, defend human rights and promote democracy. And brought Maathai the Nobel Peace Prize in 2004. .org WWW.PBS.ORG/INDEPENDENTLENS/TAKINGROOT TAKING ROOT FROM THE FILMMAKERS We first met Wangari Maathai in the spring of 2002 at the Yale School worth and therefore any sense of the common good. For us, this was of Forestry. We were at once captivated and inspired by Wangari. We palpable in the Civic and Environmental Education Seminar that was grasped immediately that her vision for change and her methods for so brilliantly facilitated by Green Belt Movement staff. change were at one and the same time interknit in a dynamic that showed its power and effectiveness in the doing rather than in political When people arrived at the seminar, they were timid. Their bodies talking and ideology. She had the moral courage to speak truth to showed that they were fearful. At the end of the first day, they were power and the patience, persistence and commitment to take action - already changed; someone was listening to them. They discovered that against enormous odds. they held the answers to their own problems. A transformation was taking place before our eyes. In Wangari's story, we could see an evolutionary path that linked seemingly disparate realms. -

Ella Fitzgerald: Just One of Those Things June 6, 8Pm

June 2021 PRIMETIME Ella Fitzgerald: Just One of Those Things June 6, 8pm Photo courtesy of Getty Images primetime 1 TUESDAY Defying the skeptics, Pan Am builds an airway to Asia. (Also Fri 4am) 7:00 OPB PBS NewsHour (Also Wed 12am) | OPB+ Nature Super Cats: Extreme Lives 8:00 OPB Oregon Art Beat Summer Arts. Portland Summer Ensembles gives students 8:00 OPB Extra Life: A Short History of Living the opportunity to play, study and perform Longer Behavior. Examine the importance of chamber music with other young musicians. persuading the public to protect themselves (Also Sun 6/20 6pm) | OPB+ Human React during a health crisis. (Also Thu 6/24 9pm (R-Also Sat 12am) OPB+) | OPB+ Shelter Me 2020/Soul Awakened. Hear uplifting stories about the 8:30 OPB Oregon Field Guide Marbled human-animal bond. (Also Thu 12am) Murrelets. Marbled murrelets have long been a mystery to science. But now their survival Darlow Smithson Productions, Ltd. 9:00 OPB Independent Lens Philly D.A., Ep 8. depends on discovering what these seabirds Frustrated Krasner supporters warn he must need to survive. (Also Sun 6/20 6:30pm) accelerate plans to phase out cash bail. Marathon (Also Thu 2am) 9:00 OPB Shakespeare & Hathaway: Private Agatha and the Truth Investigators Outrageous Fortune. Frank and 10:00 OPB Frontline The Jihadist. A powerful Lu are hired to help a dog that is heir to a vast of Murder Syrian militant called a terrorist by the U.S. | fortune. (Also Sun 2am) OPB+ Extra Life: Join the famous crime novelist seeks a new relationship with the West. -

Karen Bernstein Producer/Reporter/Editor

Karen Bernstein Producer/Reporter/Editor Bernstein Documentary 1512 ½ South Congress Ave., 2nd Floor Austin, TX 78704 917.856.2027 [email protected] Multi-media Documentary and Journalism work § Producer/ Director, I’m Gonna Make You Love Me (in progress) § Producer/ Director, Richard Linklater – dream is destiny, premiered at Sundance Film Festival, 2016, distributed by IFC Films and PBS American Masters, www.linklaterdoc.com § Radio Correspondent, KUT/ KRTS/ KXWT for news and arts programming (sample reel available on request) § Producer/ Director, TransFIGURATION, documentary for KLRU’s premier series ,Arts in Context, to be broadcast in Spring, 2014 (sample: https://vimeo.com/user6923315) § Producer/ Director, Producing Light, TeXas PBS, premiere broadcast, April 19, 2012 (sequel in the works with planned tour to Israel) https://vimeo.com/59031765 -password: Bernstein § Producer, Grant Writer, Children of Giant, with Galán Inc., funded by Latino Public Broadcasting for Voces series, June, 2014 ( https://vimeo.com/50294847 password: cog ) § Supervising Producer, Fixing The Future: NOW on PBS, JumpStart Productions, host – David Brancaccio § Project Manager/ editor, Back To Work in Far West Texas (Marfa Public Radio), Economy Response Grant from Corporation for Public Broadcasting (CPB) § Producer, A Time to Love and a Time to Hate (PBS/ Helen Whitney Productions), release: 2011 § Archive Film Researcher, Amelia (Electra Productions), Mira Nair, director, release: 2009 § Producer, YA BASTA! (Matinee Productions), www.yabastathemovie.com -

Randall Cole, 415.356.8383, Ext 254 Randall [email protected] THREE ITVS

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Contact: Randall Cole, 415.356.8383, ext 254 [email protected] THREE ITVS FILMS GARNER 2007 PEABODY AWARDS —First-time Wins for Independent Lens series and ITVS International Program— —67th Annual Awards Ceremony to Take Place on June 16, 2008— (San Francisco)—The Independent Television Service (ITVS) announced today that three of its acclaimed films are among the winners of the George Foster Peabody Awards for 2007. The Peabody Awards are the oldest and one of the most prestigious honors in electronic media. The three films being honored this year bring the grand total of ITVS Peabody Awards to 12 since opening its doors 17 years ago. BILLY STRAYHORN: LUSH LIFE and SISTERS IN LAW, both of which aired on the Emmy Award- winning PBS series Independent Lens, and the PBS mini-series CRAFT IN AMERICA: Memory, Landscape and Community were chosen to be among the 35 programs honored with this year’s Peabody Awards. In addition, this year marks the first award to a production funded through ITVS International’s Global Perspectives Project, (SISTERS IN LAW) and the first Peabodys for programs broadcast on Independent Lens. The Peabody website describes CRAFT IN AMERICA as a “three-hour chronicle of America’s rich, ongoing traditions of weaving, quilting, woodworking and other craft art…carefully wrought and as beautifully shot as its subject matter.” In describing BILLY STRAYHORN: LUSH LIFE, the website lauds: “Along with celebrating the work of the often overlooked arranger and composer who was crucial to Duke Ellington’s sound and success, the documentary sensitively explored the homophobia that kept Strayhorn in the shadows.” And finally in praise of SISTERS IN LAW: “…makes viewers flies on the wall of a small-town courthouse in Cameroon overseen by two dynamic, wisecracking, larger-than-life sisters who are helping women stand up to abuse.” The awards will be presented on June 16th at a luncheon at the Waldorf-Astoria Hotel in New York City. -

INDEPENDENT LENS Program Guide KENW-TV/FM Eastern New Mexico University January 2021

Q2 3 INDEPENDENT LENS Program Guide KENW-TV/FM Eastern New Mexico University January 2021 1 When to watch from A to Z listings for 3-1 are on pages 18 & 19 Channel 3-2 – January 2021 New Mexico Colores – Sundays, 12:00 noon (except 10th, 24th) Amanpour and Company – Tuesdays–Thursdays, 11:00 p.m. New Mexico In Focus – Sundays, 11:00 a.m. (11:30 p.m. on 26th) Nova – Wednesdays, 8:00 p.m.; Saturdays, 10:00 p.m. American Woodshop – Thursdays, 11:00 a.m.; “The Impossible Flight” (2 Hrs.) – 2nd Saturdays, 6:30 a.m. (begins 2nd) “Prediction by the Numbers” – 6th, 9th America’s Heartland – Saturdays, 6:30 p.m. “Secrets in Our DNA” – 13th, 16th America’s Test Kitchen – Saturdays, 8:00 a.m.; Tuesdays, 11:00 a.m. “Decoding da Vinci” – 20th, 23rd Antiques Roadshow – Mondays, 7:00 p.m./11:00 p.m.; “Forgotten Genius” (2 Hrs.) – 27th, 30th Mondays, 8:00 p.m. (4th only); Sundays, 7:00 a.m. Painting and Travel – Sundays, 6:00 a.m. Antiques Roadshow Recut (30 min. version) – Monday, 25th, 8:00 p.m. Paint This with Jerry Yarnell – Saturdays, 11:00 a.m. Ask This Old House – Saturdays, 4:00 p.m. P. Allen Smith’s Garden Home – Saturdays, 10:00 a.m. Austin City Limits – Saturdays, 9:00 p.m./12:00 midnight) PBS NewsHour – Weekdays, 6:00 p.m./12:00 midnight BBC World News – Weekdays, 6:30 a.m. Quilt in a Day – Saturdays, 12:30 p.m. BBC World News America – Weekdays, 5:30 p.m. -

INTRODUCTION Content Overview

2019 LOCAL CONTENT AND SERVICE REPORT TO THE COMMUNITY INTRODUCTION Content Overview The local, member-supported public media organization— Public Media Group of Southern California is dedicated Public Media Group of Southern California—was formed to telling stories that matter by creating original by a merger between KCETLink and PBS SoCal in 2018. programs that reflect the diversity of our region and The new community institution is led by the former CEO sharing the full schedule of PBS programs that viewers of PBS SoCal Andrew Russell and the Board of Trustees love and trust. Currently, we reach one of the most is chaired by former KCETLink Board chair and 38-year diverse populations in the country with the finest local, Disney veteran Richard Cook. The merged Board is national and international programming—highlighting comprised of 28 members, 14 from each original entity, important stories that foster understanding of critical with four unaffiliated positions to be filled. issues and spark dialogue. Our three channels continue to build from their current content and programming As the flagship PBS organization for the region, Public strategies and provide high-quality, culturally diverse Media Group of Southern California (PMGSC) utilizes programming designed to engage the public in the power of media for public good. We are creating a innovative, entertaining and transformative ways. new public media model that is multi-platform, diversified, modern and built around high-quality content with KCET distinctive brands. Through our three content services, The iconic Southern California public media channel KCET, PBS SoCal and Link TV, we provide our community is home to a richer and more inclusive California with an essential connection to a wider world, curate and experience, helping residents to understand and distribute content for each of our channels and provide connect with diverse communities and ideas. -

Wpsu.Org PROGRAM GUIDE FEBRUARY 2016

PROGRAM GUIDE FEBRUARY 2016 VOL. 46 NO. 2 PBS Best of Pledge Weekend... Friday, Saturday, and Sunday, February 5–7 Tune in for an entire of weekend of your favorites on WPSU, including these best-loved programs: TICKET OPPORTUNITY! Brit Floyd: Space and Time, Aging Backwards The Carpenters: Close to You Live in Amsterdam with Miranda Esmonde-White (My Music Presents) Brit Floyd pays special tribute to Pink Receive valuable insights on how to Trace the band's career, through the eyes Floyd and the era defining classic rock, combat the physical signs and of bandmates and friends, and favorites during their 2015 Space and Time tour. consequences of aging. such as "Top of the World". Friday, February 5, at 9:30 p.m. Saturday, February 6, at 3:00 p.m. Sunday, February 7, at 6:30 p.m. Make your pledge of support by calling 1-800-245-9779, or go online to wpsu.org. Democratic Presidential Ready Jet Go! Debate 2016: Advance Screening Event Saturday, February 13, at 1:00 p.m. A PBS NewsHour Special Report WPSU Studios, State College Thursday, February 11, at 9:00 p.m. The countdown has begun! Bring your little ones to WPSU for the Broadcast live from Milwaukee, Wisconsin launch of PBS Kids’ newest children’s series, Ready Jet Go! Join us just days after votes are cast in the New for an afternoon of out-of-this-world science activities, followed by Hampshire Primary and the Iowa Caucuses, interplanetary snacks and a preview screening of the first episode this will be the first time the candidates will in our television studio. -

Program Listings

WXXI-TV/HD | WORLD | CREATE | AM1370 | CLASSICAL 91.5 | WRUR 88.5 | THE LITTLE PROGRAMPUBLIC TELEVISION & PUBLIC RADIO FOR ROCHESTER LISTINGSFEBRUARY 2013 SUPER DRAMA 00 : SUNDAY FEBRUARY 3 STARTING AT 1PM ON WXXI-TV/HD 1 MANY LOVERS OF JANE AUSTEN If watching the Super Bowl on Sunday, February 3 isn’t your cup of tea, WXXI has a smashing alternative. Enjoy an afternoon of sophisticated television that we like to call Super Drama Sunday! We’ll kick off the afternoon at 1 p.m. with Many Lovers 00 of Jane Austen, which follows Austen expert and University of London Professor : Amanda Vickery as she traces the rise in popularity of Jane Austen novels. At 2 p.m., discover, if you haven’t 2 LARK RISE TO CANDLEFORD already, the heart-warming drama series Lark Rise to Candleford. An adaptation of Flora Thompson’s magical memoir of her Oxfordshire childhood, the series chronicles the daily lives of those living in the English Countryside. Then at 3 p.m., WXXI-TV gives you a 00 second chance to see episodes from season : three of the Emmy-award winning episodes from series Downton Abbey! Enjoy the first five episodes back to back. 3 DOWNTON ABBEY CLIFFORD TURNS 50! JOIN WXXI AT THE STRONG FOR A CELEBRATION FEBRUARY 2 AND 3 DETAILS INSIDE>> ANDREW ALDEN ENSEMBLE FEBRUARY 7 AT 7 PM & FEBRUARY 9 AT 3 PM, LITTLE THEATRE DETAILS INSIDE>> THE POWERBROKER: BLACK WHITNEY Young’S FIGHT FOR CIVIL RIGHTS MONDAY, FEBRUARY 25 AT 7 P.M. AT THE LITTLE THEATRE SCREENING AND PANEL DISCUSSION ARE FREE AND OPEN TO THE PUBLIC.