Oology with Dr

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Defining the Molecular Pathologies in Cloaca Malformation: Similarities Between Mouse and Human Laura A

© 2014. Published by The Company of Biologists Ltd | Disease Models & Mechanisms (2014) 7, 483-493 doi:10.1242/dmm.014530 RESEARCH ARTICLE Defining the molecular pathologies in cloaca malformation: similarities between mouse and human Laura A. Runck1, Anna Method1, Andrea Bischoff2, Marc Levitt2, Alberto Peña2, Margaret H. Collins3, Anita Gupta3, Shiva Shanmukhappa3, James M. Wells1,4 and Géraldine Guasch1,* ABSTRACT INTRODUCTION Anorectal malformations are congenital anomalies that form a Anorectal malformations are congenital anomalies that encompass spectrum of disorders, from the most benign type with excellent a wide spectrum of diseases and occur in ~1 in 5000 live births functional prognosis, to very complex, such as cloaca malformation (Levitt and Peña, 2007). The anorectal and urogenital systems arise in females in which the rectum, vagina and urethra fail to develop from a common transient embryonic structure called the cloaca that separately and instead drain via a single common channel into the exists from the fourth week of intrauterine development in humans perineum. The severity of this phenotype suggests that the defect (Fritsch et al., 2007; Kluth, 2010) and between days 10.5-12.5 post- occurs in the early stages of embryonic development of the organs fertilization in mice (Seifert et al., 2008). By the sixth week in derived from the cloaca. Owing to the inability to directly investigate humans the embryonic cloaca is divided, resulting in a ventral human embryonic cloaca development, current research has relied urogenital sinus and a separate dorsal hindgut. By the twelfth week, on the use of mouse models of anorectal malformations. However, the anal canal, vaginal and urethral openings are established. -

Evaluating and Treating the Reproductive System

18_Reproductive.qxd 8/23/2005 11:44 AM Page 519 CHAPTER 18 Evaluating and Treating the Reproductive System HEATHER L. BOWLES, DVM, D ipl ABVP-A vian , Certified in Veterinary Acupuncture (C hi Institute ) Reproductive Embryology, Anatomy and Physiology FORMATION OF THE AVIAN GONADS AND REPRODUCTIVE ANATOMY The avian gonads arise from more than one embryonic source. The medulla or core arises from the meso- nephric ducts. The outer cortex arises from a thickening of peritoneum along the root of the dorsal mesentery within the primitive gonadal ridge. Mesodermal germ cells that arise from yolk-sac endoderm migrate into this gonadal ridge, forming the ovary. The cells are initially distributed equally to both sides. In the hen, these germ cells are then preferentially distributed to the left side, and migrate from the right to the left side as well.58 Some avian species do in fact have 2 ovaries, including the brown kiwi and several raptor species. Sexual differ- entiation begins by day 5 in passerines and domestic fowl and by day 11 in raptor species. Differentiation of the ovary is characterized by development of the cortex, while the medulla develops into the testis.30,58 As the embryo develops, the germ cells undergo three phases of oogenesis. During the first phase, the oogonia actively divide for a defined time period and then stop at the first prophase of the first maturation division. During the second phase, the germ cells grow in size to become primary oocytes. This occurs approximately at the time of hatch in domestic fowl. During the third phase, oocytes complete the first maturation division to 18_Reproductive.qxd 8/23/2005 11:44 AM Page 520 520 Clinical Avian Medicine - Volume II become secondary oocytes. -

The Story of Pysanka

The Story of Pysanka A Collection of Articles on Ukrainian Easter Eggs THE STORY OF PYSANKA A Collection of Articles on Ukrainian Easter Eggs Sumtsov, Horlenko, Nomys and Others SYDNEY All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any way or form, or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, scanning, recording or otherwise without prior written permission of the publisher. Copyright © Sova Books Pty Ltd 2019 First published 2019 Editorial Board: Eugen Hlywa (†), Yuliia Vereshchak, Halyna Bondarenko, Serhiy Pjatachenko, Lesia Tolstova, Svitlana Yakovenko Copy editing: Anita Saunders Cover illustration: Mariya Luvchieva Translation: Svitlana Chornomorets Series: Ukrainian Scholar Library Book 1: The Story of Pysanka: A Collection of Articles on Ukrainian Easter Eggs ISBN: 978-0–9945334–8–7 (Paperback) A catalogue record for this book is available from the National Library of Australia The folk legends portray the egg as a source of life, and as the universe. Mykola Sumtsov, ‘Ritual egg’ (1889) Contents Acknowledgements 9 Foreword (by P. Rybalko) 11 Mykola Sumtsov . 15 Fedir Vovk . 18 Olha Kosach . 20 Volodymyr Yastrebov . 23 Kateryna Skarzhynska . 26 Matviy Nomys . 29 Vasyl Horlenko . 31 Kievskaya Starina . 32 Pysanky (by M. Sumtsov) 33 Pysanky in ancient and modern ethnography . 33 Materials used in preparation of this article . 40 Refections on the ancient symbolism of the egg in the folk tales . 42 Religious and symbolic meaning and ritual use of dyed eggs in the ancient cults . 43 Folk names of krashanky and pysanky . 49 Areas of popularity for pysanky in modern times . 51 Time of pysanky’s origin . -

Carpathian Mountains - Lviv

CNUF 55th Anniversary Tour | 2020 August 5 – 15, 2020 | 11 Days, 10 Nights Kyiv – Chernivtsi - Carpathian Mountains - Lviv Sightseeing | Workshops | Cultural Experiences | Zabavas and International Ukrainian Dance & Culture Festival Day 1| Wednesday, August 5: Arrive in Kyiv (- / - / D) Welcome to Ukraine and its capital – Kyiv! This beautiful and historic city has played a key part in the past, present and future of this country. However, Kyiv is not just an old city of Golden Domes, exciting and historical museums and memorials. It’s also a cool, up-and-coming progressive city, fast paced in some aspects, as you would expect a capital to be, but in true Ukrainian style. Upon arrival, you will be met by your Cobblestone Tour Leader at the airport (look for the Cobblestone sign with your name) and transfered to your hotel in the heart of the city. After check-in and some free time to get settled in and rest after the flight (depending on your arrival time), we will take you on a brief city orientation, pointing out the nearest exchange offices, ATMs, shops, cafes, restaurants and sights. This evening we will have our welcome dinner in one of our favorite restaurants with traditional Ukrainian food. (Throughout the tour, you Cobblestone Tour Leader will coordinate all tour details and accompany you during all your included tours, activities and transfers. They will also be on call at all times in case you need any additional services, advice or assistance.) Day 2| Thursday, August 6: Kyiv (B / - / D) After breakfast in the hotel we’ll take you on a guided walking city tour, to introduce you to Kyiv, it’s fascinating history, architecture and traditions. -

April 2020 Free Monthly Home

A P R I L 2 0 2 0 FREE MONTHLY HOME EDUCATION RESOURCE P A G E 2 Calendar Dates April 2020 11th– National Safe Motherhood day/ Na- tional Pet day/ National Submarine day/ Na- Mo Tue We Th Fri Sat Su tional Support Teen Literature day 1 2 3 4 5 12th– Easter Sunday/ Big Wind day/ Rus- 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 sian Cosmonaut day/ Walk on your Wild Side day 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 13th– Dyngus day/ International Plant Ap- 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 preciation day/ Scrabble day/ Thomas Jef- 27 28 29 30 ferson's Birthday 14th– National Look Up at the Sky day/ Na- 1st– April Fools day/ Sourdough day tional Dolphin Day 2nd– Autism Awareness day 15th– Titanic Remembrance day/ World Art day 3rd– National Find a Rainbow day/ Tweed day 16th– Mushroom day/ Save the Elephants day 4th– International Mine Awareness/ Na- tional Ferret day/ National Peanut Butter 17th– World Haemophilia day/ Bat Appreci- and Jelly day ation day/ International Haiku Poetry day 5th– Ching Ming Festival in Japan/ Na- 18th– World Heritage day/ International Jug- tional Read a Road Map day/ National glers day Nebraska day/ International Maritime 19th– National Garlic day day/ Palm Sunday 20th– Chinese Language day/ Volunteer 6th– National Tartan day Recognition day 7th- World Health day/ International Bea- 21st– National Civil Service day/ World crea- ver day/ International Reflection on tivity and innovation day/ Fish Migration day Rwanda Genocide 22nd– World Earth day/ St Georges day 8th– Draw a picture of a bird day/ Zoo lovers day/ Passover/ International Rom- 23rd– -

Avian Reproductive System—Male

eXtension Avian Reproductive System—Male articles.extension.org/pages/65373/avian-reproductive-systemmale Written by: Dr. Jacquie Jacob, University of Kentucky An understanding of the male avian reproductive system is useful for anyone who breeds chickens or other poultry. One remarkable aspect of the male avian reproductive system is that the sperm remain viable at body temperature. Consequently, the avian male reproductive tract is entirely inside the body, as shown in Figure 1. In this way, the reproductive system of male birds differs from that of male mammals. The reproductive tract in male mammals is outside the body because mammalian sperm does not remain viable at body temperature. Fig. 1. Location of the male reproductive system in a chicken. Source: Jacquie Jacob, University of Kentucky. Parts of the Male Chicken Reproductive System In the male chicken, as with other birds, the testes produce sperm, and then the sperm travel through a vas deferens to the cloaca. Figure 2 shows the main components of the reproductive tract of a male chicken. Fig. 2. Reproductive tract of a male chicken. Source: Jacquie Jacob, University of Kentucky. The male chicken has two testes, located along the chicken's back, near the top of the kidneys. The testes are elliptical and light yellow. Both gonads (testes) are developed in a male chicken, whereas a female chicken has only one mature gonad (ovary). Another difference between the sexes involves sperm production versus egg production. A rooster continues to produce new sperm while it is sexually mature. A female chicken, on the other hand, hatches with the total number of ova it will ever have; that is, no new ova are produced after a female chick hatches. -

Reptilian Renal Structure and Function

REPTILIAN RENAL STRUCTURE AND FUNCTION Jeanette Wyneken, PhD Florida Atlantic University, Dept. of Biological Sciences, 777 Glades Rd, Boca Raton, FL 33431 USA ABSTRACT This overview focuses on the urinary component of the urogenital system. Here I define terms, synthesize the relevant literature on reptilian renal structure, discuss structural – functional relationships, and provide comparisons to other vertebrate renal form and function. The urinary and reproductive components of the urogenital system develop in conjunction with one another from two adjacent parts of the mesoderm. As development proceeds, ducts that drain nitrogenous wastes in the embryo are co-opted by the reproductive system or they regress (e.g., mesonephric ducts become the Müllarian ducts in females, pronephric ducts become the Ductus deferens in males) and new ducts (ureters) form to drain the kidneys. Urogenital System Consists of Kidneys, Gonads and Duct Systems • Urinary system is formed by the kidneys, including their nephrons (= nephric tubules) and collecting ducts. The collecting ducts drain products from the nephrons into to ureters that themselves drain to the cloaca via the (usually paired) urogenital papillae in the dorsolateral cloacal wall. A urinary bladder that opens in the floor of the cloaca may or may not be present depending upon species. • The genital system (gonads and their ducts) forms later in development and is discussed here only when relevant to urinary function. Kidney Form and Terminology The literature includes a number of descriptive terms for the developing kidney that often confuse more than clarify the form of the kidney. Understanding the basics of kidney development should help. The kidneys arise as paired structures from embryonic mesoderm. -

SHARK DISSECTION INSTRUCTIONS Part 1: External

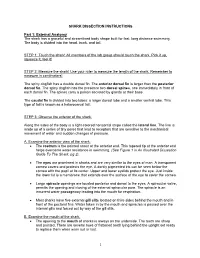

SHARK DISSECTION INSTRUCTIONS Part 1: External Anatomy The shark has a graceful and streamlined body shape built for fast, long distance swimming. The body is divided into the head, trunk, and tail. STEP 1: Touch the shark! All members of the lab group should touch the shark. Pick it up, squeeze it, feel it! STEP 2: Measure the shark! Use your ruler to measure the length of the shark. Remember to measure in centimeters! The spiny dogfish has a double dorsal fin. The anterior dorsal fin is larger than the posterior dorsal fin. The spiny dogfish has the presence two dorsal spines, one immediately in front of each dorsal fin. The spines carry a poison secreted by glands at their base. The caudal fin is divided into two lobes: a larger dorsal lobe and a smaller ventral lobe. This type of tail is known as a heterocercal tail. STEP 3: Observe the exterior of the shark. Along the sides of the body is a light-colored horizontal stripe called the lateral line. The line is made up of a series of tiny pores that lead to receptors that are sensitive to the mechanical movement of water and sudden changes of pressure. A. Examine the anterior view of the shark. • The rostrum is the pointed snout at the anterior end. This tapered tip at the anterior end helps overcome water resistance in swimming. (See Figure 1 in An Illustrated Dissection Guide To The Shark, pg 2). • The eyes are prominent in sharks and are very similar to the eyes of man. -

Beaver Fact Sheet

BEAVER Castor canadensis The beaver (Castor canadensis) is the largest rodent in North America. It is easily recognized by its large, flat, bare, scaled tail and fully webbed rear feet. Beaver range in North America includes most of the United States and southern Canada. The beaver played an important role in the early colonization of North America, as trappers came in search of pelts. At one time, the beaver population had declined to the point that they were absent from most of their range. However today, beaver populations have rebounded and, in some areas, they create conflicts with humans. Vermont Wildlife Fact Sheet Physical Description A beaver’s head is relatively similar to that of an aquatic small and round with large, well mammal than a terrestrial one. Beavers normally have dark developed incisor teeth for brown fur with lighter highlights gnawing wood. As with other The front feet of a beaver are but some with black, white, and rodents, these teeth grow not webbed, but have strong silver coats have been reported. continually. If opposing teeth do claws for digging. Front legs are The under fur is very dense, not match correctly, allowing tucked up against the chest short, and waterproof, with normal wearing and sharpening when the beaver swims. The sparse, coarse, shiny guard hairs action, they can grow rear feet are large and webbed protruding through. excessively to the point where for powerful swimming and provide support when walking An average adult beaver eating is nearly impossible and starvation results. Flat-surfaced over mud, like snowshoes. weighs 40 to 60 pounds. -

Khrystos Voskres» (Christ Risen)

Theme of the lesson Celebration of Easter in Ukraine and Great Britain Phonetic drill Easter- is in spring What will it bring? Easter cakes, painted eggs In beautiful baskets and bags Hope in hearts we will got, And forgiveness from God. Collocations • 1 religious a) cultures • 2 ancient b) holiday • 3 Christ c) church • 4 go to d) risen • 5 eate) museum • 6 painted f) countries • 7 Pysanka g) Easter cakes • 8 foreign h)egg • Jesus [ ˈʤiːzəs ] • Origin [ ˈɒrɪdʒɪn ] • Ancient [ ˈeɪnʃənt ] • Ritual [ ˈrɪt.ju.əl ] • Associated [ əˈsəʊʃieɪtɪd ] • Foreign [ ˈfɒrin ] • Christ [ kraɪst ] • Precios [ ˈpreʃ.əs ] • Church [ tʃɜː:tʃ ] Easter • Easter is a great religious holiday. • 1------------------------------------------------ • On Easter morning many people go to church.They carry Easter baskets where they have Easter cakes and Easter eggs,sausages, sault, butter,meat. Then they come home and have a holiday breakfast.In Ukraine we usually eat Easter cakes called «paskas» and coloured eggs called «pysankas» and «krashankas». • Pysanka and krashanka are the traditional Ukrainian Easter eggs. • 2------------------------------------------------- • There are usually beautiful ornaments and symbols on pysankas. • The symbol of an egg is present in many ancient cultures of the world. • 3_______________________________________________________ • Many rituals are associated with pysankas. The first Easter meal begins with an Easter egg. • 4 _______________________________________________________ • In the Ukrainian town of Kolomyya, there is a Pysanka museum, the only museum of this kind in Ukraine. • 5 ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Put the sentences into the correct order • People celebrate this holiday on Sunday in spring. • Pysanka is a decorated egg and krashanka is a painted egg. • Easter eggs can be made of stone, metal, or wood and decorated with precious stones. -

Gross and Microscopic Anatomy of the Structures

GROSS AND MICROSCOPIC ANATOMY OF THE STRUCTURES INVOLVED IN THE PRODUCTION OF SEMINAL FLUID IN THE CHICKEN BY Carl Edward Knight A THESIS Submitted to Michigan State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE Department of Poultry Science 1967 5// ABSTRACT GROSS AND MICROSCOPIC ANATOMY OF THE STRUCTURES INVOLVED IN THE PRODUCTION OF SEMINAL FLUID IN THE CHICKEN by Carl Edward Knight The gross and microscopic anatomy of the structures involved in the production of seminal fluid in the chicken are discussed. The phallus, round bodies, lymph folds and vascular bodies were found to be the structures directly involved in seminal fluid production. Sur- rounding structures were discussed for orientation and illustrations were presented to complement the discussion. The-cloaca is composed of three chambers; proctodeum, urodeum, and coprodeum. Externally it appears as two lips, a larger dorsal lip and a smaller ventral lip. Its surface is covered with epithelium characteristic of the general body surface. The proctodeal fold arises from the margin of the lips and forms the cloacal opening by its incomplete central fusion. The proctodeal cavity is the most caudal of the cloacal chambers. The phallus, round bodies and lymph folds lie in this chamber. The opening to the cloacal bursa is found in the dorsal aspect of this chamber. The uroproctodeal fold forms the cranial boundary of the proctodeum and the caudal boundary of the urodeum. The urodeum is Carl Edward Knight the middle chamber of the cloaca. The ejaculatory papillae and ureters empty into this chamber. The uroproctodeal fold forms the cranial boundary of the urodeum and the caudal boundary of the coprodeum. -

Ready Player One by Ernest Cline

Ready Player One by Ernest Cline Chapter 1 Everyone my age remembers where they were and what they were doing when they first heard about the contest. I was sitting in my hideout watching cartoons when the news bulletin broke in on my video feed, announcing that James Halliday had died during the night. I’d heard of Halliday, of course. Everyone had. He was the videogame designer responsible for creating the OASIS, a massively multiplayer online game that had gradually evolved into the globally networked virtual reality most of humanity now used on a daily basis. The unprecedented success of the OASIS had made Halliday one of the wealthiest people in the world. At first, I couldn’t understand why the media was making such a big deal of the billionaire’s death. After all, the people of Planet Earth had other concerns. The ongoing energy crisis. Catastrophic climate change. Widespread famine, poverty, and disease. Half a dozen wars. You know: “dogs and cats living together … mass hysteria!” Normally, the newsfeeds didn’t interrupt everyone’s interactive sitcoms and soap operas unless something really major had happened. Like the outbreak of some new killer virus, or another major city vanishing in a mushroom cloud. Big stuff like that. As famous as he was, Halliday’s death should have warranted only a brief segment on the evening news, so the unwashed masses could shake their heads in envy when the newscasters announced the obscenely large amount of money that would be doled out to the rich man’s heirs. 2 But that was the rub.