Jumpstarting Agribusiness Markets

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Etc Status with 21Confcase 1.Pdf

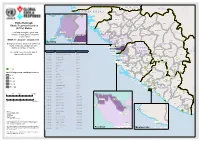

SE N E G A L M A L I GU IN EA -B IS SA U Koundara Mali ETC"-GIN-003 Koubia Gaoual Lelouma Dinguiraye Siguiri Ebola Outbreak: Labe Tougue Ebola Treatment Centres Telimele (ETCs) Status Dalaba Kouroussa Boke This Map shows the status and ETC"-GIN-012 Pita Mandiana Boffa Dabola location of each Ebola Treatment Mamou Fria Center (ETC). ETC"-GIN-001 ETC"-GIN-018 Dubreka Kindia Faranah ETC-GIN-015 WEEK 17: 20 April - 26 April 2015 " Kankan Conakry Copyright:© 2014 Esri Background colour show new confirmed Koinadugu ETC-GIN-00C3 oyah G U I N E A " Bombali cases for the last 21 days for each ConakryETC-GIN-012 district, prefecture or county. ETC"-EGT"ICN"-G00IN1-018 S I E R R A Kissidougou CÔ TE ETC-GIN-017 ETC CODE Site Name Country Forecariah " L E O N E Kerouane D' IV OI R E The number over the ETC sign is ETC-GIN-001 Conakry Region Guinea Beyla Freetownreferenced in the table. ETC-GIN-003 Kindia Region, Coyah Prefecture Guinea Kambia ETC"-SLE-034 ETC-SLE-008 ETC-GIN-007 Nzérékoré Region Guinea " Kono Gueckedou ETC-GIN-009 Nzérékoré Region Guinea Port Loko EETTCC--SSLLEE--00002571 ETC-SLE-022 "" " ETC-GIN-009 ETC-GIN-010 Nzérékoré Region Guinea ETC-SLE-031 " " ETC-GIN-010 Western " ETC-GIN-011 ETC-GIN-011 Nzérékoré Region Guinea Area Urban ETECT-SCL-SEL-0E2-4028 Tonkolili " ETC-LBR-011 ETC-GIN-012 Conakry Region Guinea "E"ETTC"C--SSLLEE--00121375 ETECT"-CS-LSEL-E0-2303226 " ETC-GIN-015 Kindia Guinea ET"C"-SLE-0116 Lofa Macenta Western " " ETC-SLE-009 ETC-GIN-017 Forecariah Guinea Area Rural " ETC-GIN-018 Conakry Guinea ETC-SLE-004 Nzerekore -

Cloth, Commerce and History in Western Africa 1700-1850

The Texture of Change: Cloth, Commerce and History in Western Africa 1700-1850 The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Benjamin, Jody A. 2016. The Texture of Change: Cloth, Commerce and History in Western Africa 1700-1850. Doctoral dissertation, Harvard University, Graduate School of Arts & Sciences. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:33493374 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA The Texture of Change: Cloth Commerce and History in West Africa, 1700-1850 A dissertation presented by Jody A. Benjamin to The Department of African and African American Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the subject of African and African American Studies Harvard University Cambridge, Massachusetts May 2016 © 2016 Jody A. Benjamin All rights reserved. Dissertation Adviser: Professor Emmanuel Akyeampong Jody A. Benjamin The Texture of Change: Cloth Commerce and History in West Africa, 1700-1850 Abstract This study re-examines historical change in western Africa during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries through the lens of cotton textiles; that is by focusing on the production, exchange and consumption of cotton cloth, including the evolution of clothing practices, through which the region interacted with other parts of the world. It advances a recent scholarly emphasis to re-assert the centrality of African societies to the history of the early modern trade diasporas that shaped developments around the Atlantic Ocean. -

PRSP II) for Guinea and the Public Disclosure Authorized Joint IDA-IMF Staff Advisory Note (JSAN) on the PRSP II

OFFICIAL USE ONLY IDA/SecM2007-0684 December 12, 2007 Public Disclosure Authorized For meeting of Board: Tuesday, January 8, 2008 FROM: Vice President and Corporate Secretary Guinea: Second Poverty Reduction Strategy Paper and Joint IDA-IMF Staff Advisory Note 1. Attached is the Second Poverty Reduction Strategy Paper (PRSP II) for Guinea and the Public Disclosure Authorized Joint IDA-IMF Staff Advisory Note (JSAN) on the PRSP II. The IMF is currently scheduled to discuss this document on December 21, 2007. 2. The PRSP II was prepared by the Government of Guinea. The paper acknowledges the disappointing outcome of the first PRSP, which covered the period 2002-2006. The political, social and economic environment in which the implementation of PRSP I took place was characterized by poor governance, political instability, and low growth which led to an increase in poverty from 49 percent in 2002 to an estimated 54 percent in 2005. Overall, public service delivery deteriorated in terms of both quality and access and the living conditions for most Guineans worsened. Public Disclosure Authorized 3. PRSP II aims at recapturing lost ground over the past five years. The overall strategy is based on three pillars: (i) improving governance; (ii) accelerating growth and increasing employment opportunities; and (iii) improving access to basic services. It focuses on restoring macroeconomic stability, institutional and structural reforms, and mechanisms to strengthen the democratic process implementation capacity. 4. As approved by the Board on August 6, 2007, the pilot Board Technical Questions and Answer Database (http://boardqa.worldbank.org or from the EDs' portal) is now open for questions. -

Recipient UN Organization(S): UNICEF UNDP Proposal Contacts

EBOLA RESPONSE MULTI-PARTNER TRUST FUND PROPOSAL Proposal Title: Stop Ebola through social Recipient UN Organization(s): mobilization and community engagement in Guinea UNICEF UNDP Proposal Contacts: Implementing Partner(s) – name & type For UNICEF (Government, CSO, etc.): Dr Mohamed Ayoya - NGOs: Plan Guinée, CERAD, Resident Representative CENAFOD, CNOSCG; youth Address: UNICEF, Corniche, Coleah, Conakry organizations Telephone: +224 622 663 452 - Government. E-mail: [email protected] For UNDP Aissatou Cisse-Yao Yao Deputy Country Director, Programme Address:UNDP Guinée Maison Commune Coléah Commune de Matam BP : 222 Conakry République de Guinée Telephone: 224 622 35 54 69 E-mail: [email protected] Proposal Location (country): Proposal Location (provinces): Please select one from the following Conakry, Boke, Kindia, Mamou, Faranah, Guinea Kankan, Nzerekore. Liberia (see map in Annex for detailed targets locations) Sierra Leone Common Services Project Description: Requested amount: One sentence describing the project’s scope and focus. USD 3,139,364 UNICEF USD 809,000 UNDP Through social mobilization, with a particular focus on Total requested amount: USD 3,948,364 vulnerable and at-risk groups such as women and youth, UNICEF and UNDP will support communities Other sources of funding of this proposal: to setup Community Watch Committees (CWCs), UNICEF regular resources door-to-door sensitization and referral of Ebola UNDP core fund suspected and contact cases. UNMEER budget: Other sources (indicate): Government Input: in kind support 1 Start Date: 10 December 2014 End Date: 15 June 2015 Total duration (in months): 6 months MISSION CRITICAL ACTIONS to which the proposal is contributing. For reporting purposes, each project should contribute to one SO. -

PRADD II Guinea Impact Evaluation Design Report

EVALUATION, RESEARCH AND COMMUNICATION (ERC) Property Rights and Artisanal Diamond Development Project II (PRADD II) Impact Evaluation Design Report AUGUST 2014 This document was produced for review by the United States Agency for International Development. It was prepared by Cloudburst Consulting Group, Inc. for the Evaluation, Research, and Communication (ERC) Task Order under the Strengthening Tenure and Resource Rights (STARR) IQC. Written and prepared by Heather Huntington, Michael McGovern, and Darrin Christensen. Prepared for the United States Agency for International Development, USAID Contract Number AID- OAA-TO-13-00019, Evaluation, Research and Communication (ERC) Task Order under Strengthening Tenure and Resource Rights (STARR) IQC No. AID-OAA-I-12-00030. Implemented by: Cloudburst Consulting Group, Inc. 8400 Corporate Drive, Suite 550 Landover, MD 20785-2238 EVALUATION, RESEARCH AND COMMUNICATION (ERC) Property Rights and Artisanal Diamond Development Project II (PRADD II) Impact Evaluation Design Report AUGUST 2014 DISCLAIMER The authors' views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Agency for International Development or the United States Government. CONTENTS 36T36TCONTENTS36T36T ............................................................................................................................ 4 36T36TACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS36T36T ..................................................................................... 5 36T36T1.0 INTRODUCTION36T36T .............................................................................................................. -

Appraisal Report Kankan-Kouremale-Bamako Road Multinational Guinea-Mali

AFRICAN DEVELOPMENT FUND ZZZ/PTTR/2000/01 Language: English Original: French APPRAISAL REPORT KANKAN-KOUREMALE-BAMAKO ROAD MULTINATIONAL GUINEA-MALI COUNTRY DEPARTMENT OCDW WEST REGION JANUARY 1999 SCCD : N.G. TABLE OF CONTENTS Page PROJECT INFORMATION BRIEF, EQUIVALENTS, ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS, LIST OF ANNEXES AND TABLES, BASIC DATA, PROJECT LOGICAL FRAMEWORK, ANALYTICAL SUMMARY i-ix 1 INTRODUCTION.............................................................................................................. 1 1.1 Project Genesis and Background.................................................................................... 1 1.2 Performance of Similar Projects..................................................................................... 2 2 THE TRANSPORT SECTOR ........................................................................................... 3 2.1 The Transport Sector in the Two Countries ................................................................... 3 2.2 Transport Policy, Planning and Coordination ................................................................ 4 2.3 Transport Sector Constraints.......................................................................................... 4 3 THE ROAD SUB-SECTOR .............................................................................................. 5 3.1 The Road Network ......................................................................................................... 5 3.2 The Automobile Fleet and Traffic................................................................................. -

Guinea : Reference Map of Kankan Region (As of 3 March 2015)

Guinea : Reference Map of Kankan Region (as of 3 March 2015) Bankolen Mambifagalena Niagassola Kry Tourelen Berlen Sokoromansa Magadiano Faraboloni Linkekoro KIGNEKOUROU CENTRE Bouyido Malsadou Seourou Konfara 2 Gnembou Tanssa Magnaka KOTE CENTRE Balenda SOUMBARAYA CENTRE Kourelen TALABE CENTRE Dialawassa II Kondoko Djanwely Itipony Dougounta Dora Kourakoda DIBIA CENTRE Djinko Ilimalo Naboun Kanimbakalako Kodougoulen KAKAMA CENTRE Tondo Komagron Kayaga Kignedi Sininko Kadabili Kignero Gnere Sininkoro Badamako Kounsounkoro Yirikelèma Kanikoumbaya SOKORO CENTRE DIATEA CENTRE Dita Salla Tondji1 Koda Kebesabaya Siguirini Sakounou Malea Bembéta Megnèkoma Silabado Diakan Toukönö BOULAN CENTRE Gbèdela MANKADIAN CENTRE Gbörökola Doko Tombani Maragbè Kana Sékela Mansadji Sidao Tonso Banankölö Tomba Doula Amina Amina Kinièba Franwalia Tinko Diatifere Fountou Soumbalakölen Iroda Kounkoun Koda Mainou SARAYA CENTRE Tomboni Sinimbaya KOBEDRA CENTRE MIGNADA CENTRE Bökökö Farani Banora Simbona Bida Tomba Boufe Bandioula FOULATA CENTRE Kintinian Yorola Tougnou Sanouna SEELA CENTRE Bankon MALI Tinkoba Kobada Beretela Sando Noumandiana Kandani Fodela Bèrèko Tabakoro BAMBALA Tabako Madila Moyafara Kourouni Banantamou Siguiri FALAMA BANFARA CENTRE Saint Alexis Dialakoro Nedekoroko Banantou Lansanaya Sakolado Manakoro Farabada Dounin Farabelen Bida Bantambaye Woléwoléya Koda Koda Kogne Tambabougou Gbongoroma Kigne Kokoudouninda Dinguiraye Gbilin Balandougouba KONKOYE CENTRE Waran-Fougou Kiniebakoura DIARRADOU CENTRE Sansani Faradjian Tassiliman Centre Kewoulé -

Observing the 2010 Presidential Elections in Guinea

Observing the 2010 Presidential Elections in Guinea Final Report Waging Peace. Fighting Disease. Building Hope. Map of Guinea1 1 For the purposes of this report, we will be using the following names for the regions of Guinea: Upper Guinea, Middle Guinea, Lower Guinea, and the Forest Region. Observing the 2010 Presidential Elections in Guinea Final Report One Copenhill 453 Freedom Parkway Atlanta, GA 30307 (404) 420-5188 Fax (404) 420-5196 www.cartercenter.org The Carter Center Contents Foreword ..................................1 Proxy Voting and Participation of Executive Summary .........................2 Marginalized Groups ......................43 The Carter Center Election Access for Domestic Observers and Observation Mission in Guinea ...............5 Party Representatives ......................44 The Story of the Guinean Security ................................45 Presidential Elections ........................8 Closing and Counting ......................46 Electoral History and Political Background Tabulation .............................48 Before 2008 ..............................8 Election Dispute Resolution and the From the CNDD Regime to the Results Process ...........................51 Transition Period ..........................9 Disputes Regarding First-Round Results ........53 Chronology of the First and Disputes Regarding Second-Round Results ......54 Second Rounds ...........................10 Conclusion and Recommendations for Electoral Institutions and the Framework for the Future Elections ...........................57 -

ISO 3166-2 NEWSLETTER Changes in the List of Subdivision Names And

ISO 3166-2 NEWSLETTER Date issued: 2010-02-03 No II-1 Corrected and reissued 2010-02-19 Changes in the list of subdivision names and code elements The ISO 3166 Maintenance Agency1) has agreed to effect changes to the header information, the list of subdivision names or the code elements of various countries listed in ISO 3166-2:2007 Codes for the representation of names of countries and their subdivisions — Part 2: Country subdivision code. The changes are based on information obtained from either national sources of the countries concerned or on information gathered by the Panel of Experts for the Maintenance of ISO 3166-2. ISO 3166-2 Newsletters are issued by the secretariat of the ISO 3166/MA when changes in the code lists of ISO 3166-2 have been decided upon by the ISO 3166/MA. ISO 3166-2 Newsletters are identified by a two-component number, stating the currently valid edition of ISO 3166-2 in Roman numerals (e.g. "I") and a consecutive order number (in Latin numerals) starting with "1" for each new edition of ISO 3166-2. For all countries affected a complete new entry is given in this Newsletter. A new entry replaces an old one in its entirety. The changes take effect on the date of publication of this Newsletter. The modified entries are listed from page 4 onwards. For reasons of user-friendliness, changes have been marked in red (additions) or in blue (deletions). The table below gives a short overview of the changes made. This Newsletter was initially issued 2010-02-03 and the entry for Serbia was incomplete and this Newsletter was reissued 2010-02-19. -

For Personal Use Only Use Personal For

Mt Edon House 2nd Floor,West Apartment, Hse 2/7 Inner Road, 30 Ledgar Rd Immeuble Archêvèche, Cantonments, Accra Balcatta WA Conakry Ghana Australia Républic De Guinée P. +233 021 782348 P. +61 8 9240 7660 B.P. 3938 Conakry F. +61 8 9240 2406 Républic De Guinée A.B.N. 14 113 517 203 P. +8821 621 153 527 www.bureygold.com 29 April 2011 MARCH 2011 QUARTERLY ACTIVITY REPORT HIGHLIGHTS Balatindi Project • A total of 10 sub-vertical HQ diamond drill holes were completed for a total of 3,468.6 metres. • An additional 22 reverse circulation (RC) drill holes for 1,848 metres tested the substrate of five areas, designated anomalies A to E, of substantial surface radiometric anomalism and associated alteration. Kossanke Project • Refurbishment of the previous field camp, Farassabeben, on the Kossanke Licence area is currently in progress. • Executed an agreement with local company Societe Bossoba sarlu allowing Burey to earn an 80% interest in the Celein exploration licence, Mandiana Prefecture, Guinea Post Period Highlights • By the end of April 2011, Burey had completed approximately 25% of a 7,000m RC infill and extension program at the Mansounia Project in 15 RC drill holes for approximately 1,500 metres. • Contracted exploration consulting group SEMS Exploration Services, which has started preparatory logistics work to allow commencement of a soil sampling program at the Kossanke and Celein Licences in May. • It is anticipated that all assay results for gold and the associated multi-element ICP MS analytical process which have been returned to date (with most of the polymetallic ICP results still awaited) from the initial six holes of the ten hole programme which investigated the Balatindi polymetallic occurrence, will be released in early May. -

GSV2.1 LSC Report BISS V2 August 2011

GOLD STANDARD LOCAL STAKEHOLDER CONSULTATION REPORT CONTENTS A. Project Description 1. Project eligibility under Gold Standard 2. Current project status B. Design of Stakeholder Consultation Process 1. Description of physical meeting(s) i. Agenda ii. Non-technical summary iii. Invitation tracking table iv. Text of individual invitations v. Text of public invitations 2. Description of other consultation methods used C. Consultation Process 1. Participants’ in physical meeting(s) i. List ii. Evaluation forms 2. Pictures from physical meeting(s) 3. Outcome of consultation process i. Minutes of physical meeting(s) ii. Minutes of other consultations iii. Assessment of all comments iv. Revisit sustainable development assessment v. Summary of changes to project design based on comments D. Sustainable Development Assessment 1. Own sustainable development assessment i. ‘Do no harm’ assessment ii. Sustainable development matrix 2. Stakeholders blind sustainable development matrix 3. Consolidated sustainable development matrix E. Discussion on Sustainability Monitoring Plan F. Description of Stakeholder Feedback Round Annex 1. Original participants list Annex 2. Original feedback forms Annex 3. Original non-technical summary SECTION A. PROJECT DESCRIPTION A. 1. Project eligibility under the Gold Standard The efficient cook stove project in Guinea falls under the “End-use Energy Efficiency Improvement” category as mentioned in the GS Toolkit Annexes. The project will generate an annual average GHG emissions reduction volume around 8000 teqCO2. According to the Gold Standard classification, the Project is qualified as a “small scale project”. A. 2. Current project status General description of the project: The purpose of the project is to improve conditions of Guinean households in Kindia area (Republic of Guinea) and fight against global warming and deforestation by promoting the use of an efficient cook stove (vernacular name: « kolpot fötönkanté »). -

MCHIP Guinea End-Of-Project Report October 2010–June 2014

MCHIP Guinea End-of-Project Report October 2010–June 2014 Submitted on: September 15, 2014 Submitted to: United States Agency for International Development under Coooperative Agreement # GHS-A-00-08-00002-000 Submitted by: Yolande Hyjazi, Rachel Waxman and Bethany Arnold 1 The Maternal and Child Health Integrated Program (MCHIP) is the USAID Bureau for Global Health’s flagship maternal, neonatal and child health (MNCH) program. MCHIP supports programming in maternal, newborn and child health, immunization, family planning, malaria, nutrition, and HIV/AIDS, and strongly encourages opportunities for integration. Cross-cutting technical areas include water, sanitation, hygiene, urban health and health systems strengthening. MCHIP brings together a partnership of organizations with demonstrated success in reducing maternal, newborn and child mortality rates and malnutrition. Each partner will take the lead in developing programs around specific technical areas: Jhpiego, as the Prime, will lead maternal health, family planning/reproductive health, and prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV (PMTCT); JSI—child health, immunization, and pediatric AIDS; Save the Children—newborn health, community interventions for MNCH, and community mobilization; PATH—nutrition and health technology; JHU/IIP—research and evaluation; Broad Branch—health financing; PSI—social marketing; and ICF International—continues support for the Child Survival and Health Grants Program (CSHGP) and the Malaria Communities Program (MCP). This report was made possible by the generous support of the American people through the United States Agency for International Development (USAID), under the terms of the Leader with Associates Cooperative Agreement GHS-A-00-08-00002-00. The contents are the responsibility of the Maternal and Child Health Integrated Program (MCHIP) and do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID or the United States Government.