Online Appendix for “Critical Junctures:Independence Movements and Democracy in Africa”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Appraisal Report Kankan-Kouremale-Bamako Road Multinational Guinea-Mali

AFRICAN DEVELOPMENT FUND ZZZ/PTTR/2000/01 Language: English Original: French APPRAISAL REPORT KANKAN-KOUREMALE-BAMAKO ROAD MULTINATIONAL GUINEA-MALI COUNTRY DEPARTMENT OCDW WEST REGION JANUARY 1999 SCCD : N.G. TABLE OF CONTENTS Page PROJECT INFORMATION BRIEF, EQUIVALENTS, ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS, LIST OF ANNEXES AND TABLES, BASIC DATA, PROJECT LOGICAL FRAMEWORK, ANALYTICAL SUMMARY i-ix 1 INTRODUCTION.............................................................................................................. 1 1.1 Project Genesis and Background.................................................................................... 1 1.2 Performance of Similar Projects..................................................................................... 2 2 THE TRANSPORT SECTOR ........................................................................................... 3 2.1 The Transport Sector in the Two Countries ................................................................... 3 2.2 Transport Policy, Planning and Coordination ................................................................ 4 2.3 Transport Sector Constraints.......................................................................................... 4 3 THE ROAD SUB-SECTOR .............................................................................................. 5 3.1 The Road Network ......................................................................................................... 5 3.2 The Automobile Fleet and Traffic................................................................................. -

Observing the 2010 Presidential Elections in Guinea

Observing the 2010 Presidential Elections in Guinea Final Report Waging Peace. Fighting Disease. Building Hope. Map of Guinea1 1 For the purposes of this report, we will be using the following names for the regions of Guinea: Upper Guinea, Middle Guinea, Lower Guinea, and the Forest Region. Observing the 2010 Presidential Elections in Guinea Final Report One Copenhill 453 Freedom Parkway Atlanta, GA 30307 (404) 420-5188 Fax (404) 420-5196 www.cartercenter.org The Carter Center Contents Foreword ..................................1 Proxy Voting and Participation of Executive Summary .........................2 Marginalized Groups ......................43 The Carter Center Election Access for Domestic Observers and Observation Mission in Guinea ...............5 Party Representatives ......................44 The Story of the Guinean Security ................................45 Presidential Elections ........................8 Closing and Counting ......................46 Electoral History and Political Background Tabulation .............................48 Before 2008 ..............................8 Election Dispute Resolution and the From the CNDD Regime to the Results Process ...........................51 Transition Period ..........................9 Disputes Regarding First-Round Results ........53 Chronology of the First and Disputes Regarding Second-Round Results ......54 Second Rounds ...........................10 Conclusion and Recommendations for Electoral Institutions and the Framework for the Future Elections ...........................57 -

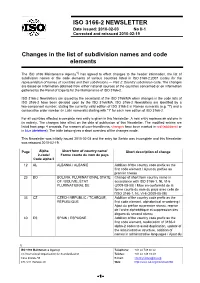

ISO 3166-2 NEWSLETTER Changes in the List of Subdivision Names And

ISO 3166-2 NEWSLETTER Date issued: 2010-02-03 No II-1 Corrected and reissued 2010-02-19 Changes in the list of subdivision names and code elements The ISO 3166 Maintenance Agency1) has agreed to effect changes to the header information, the list of subdivision names or the code elements of various countries listed in ISO 3166-2:2007 Codes for the representation of names of countries and their subdivisions — Part 2: Country subdivision code. The changes are based on information obtained from either national sources of the countries concerned or on information gathered by the Panel of Experts for the Maintenance of ISO 3166-2. ISO 3166-2 Newsletters are issued by the secretariat of the ISO 3166/MA when changes in the code lists of ISO 3166-2 have been decided upon by the ISO 3166/MA. ISO 3166-2 Newsletters are identified by a two-component number, stating the currently valid edition of ISO 3166-2 in Roman numerals (e.g. "I") and a consecutive order number (in Latin numerals) starting with "1" for each new edition of ISO 3166-2. For all countries affected a complete new entry is given in this Newsletter. A new entry replaces an old one in its entirety. The changes take effect on the date of publication of this Newsletter. The modified entries are listed from page 4 onwards. For reasons of user-friendliness, changes have been marked in red (additions) or in blue (deletions). The table below gives a short overview of the changes made. This Newsletter was initially issued 2010-02-03 and the entry for Serbia was incomplete and this Newsletter was reissued 2010-02-19. -

West and Central Africa Region COVID-19

West and Central Africa Region COVID-19 Situation Report No. 5 © UNFPA United Nations Population Fund Reporting Period: 1 - 30 June 2020 Regional Highlights Situation in Numbers ● The total number of COVID-19 positive cases has 110,233 Confirmed COVID-19 Cases reached over 100,000 in all 23 countries in West and Central Africa, four months after the first case 2,065 COVID-19 Deaths was reported in Nigeria. By the end of June, there were nearly 2,000 deaths, a mortality rate of about 1.9 per cent. Two of every five patients were still Source: WHO 2 July 2020 hospitalized, while 55% had recovered. ● The pandemic continues to spread at an average Key Population Groups rate of 2,206 new cases per day over the last 7 days. Three countries leading with caseloads are Nigeria (25,133), Ghana (17,351) and Cameroon 13 M Pregnant Women (12,592). ● Chad (90%) and Burkina Faso (87%) have the 108 M Women of Reproductive Age highest percentage of recovery, while Chad (8.5%) and Niger (6.2%) have highest case fatality rates. 148 M Young People (age 10-24) ● UNFPA Country Offices continue making strategic interventions, in collaboration with partners, to support governments to respond to the COVID-19 13 M Older Persons (age 65+) pandemic across the region. ● About 15,000 safe deliveries were recorded in Funding Status for Region (US$) UNFPA-supported facilities in Senegal (7,779), Benin (3,647), Togo (2,588), Sierra Leone (818). ● Over 108,775 women and youth have utilised Funds Allocated integrated sexual and reproductive health (SRH) 27.6 M services in UNFPA-support facilities in the region. -

The Roots of Conflicts in Guinea-Bissau

Roots of Conflicts in Guinea-Bissau: The voice of the people Title: Roots of Conflicts in Guinea-Bissau: The voice of the people Authors: Voz di Paz Date: August 2010 Published by: Voz di Paz / Interpeace ©Voz di Paz and Interpeace, 2010 All rights reserved Produced in Guinea-Bissau The views expressed in this publication are those of the key stakeholders and do not necessarily represent those of the sponsors. Reproduction of figures or short excerpts from this report is authorized free of charge and without formal written permission provided that the original source is properly acknowledged, with mention of the complete name of the report, the publishers and the numbering of the page(s) or the figure(s). Permission can only be granted to use the material exactly as in the report. Please be aware that figures cannot be altered in any way, including the full legend. For media use it is sufficient to cite the source while using the original graphic or figure. This is a translation from the Portuguese original. Cover page photo: Voz di Paz About Voz di Paz “Voz di Paz – Iniciativa para Consolidação da Paz” (Voice of Peace – An initiative for the consolidation of Peace) is a Bissau-Guinean non-governmental organization (NGO) based in the capital city, Bissau. The Roots of Conflicts in Guinea-Bissau: The mission of Voz di Paz is to support local actors, as well as national and regional authorities, to respond more effectively to the challenges of consolidating peace and contribute to preventing future conflict. The approach promotes participation, strengthens local capacity and accountability, The voice of the people and builds national ownership. -

Republic of Guinea: Overcoming Growth Stagnation to Reduce Poverty

Report No. 123649-GN Public Disclosure Authorized REPUBLIC OF GUINEA OVERCOMING GROWTH STAGNATION TO REDUCE POVERTY Public Disclosure Authorized SYSTEMATIC COUNTRY DIAGNOSTIC March 16, 2018 International Development Association Country Department AFCF2 Public Disclosure Authorized Africa Region International Finance Corporation Sub-Saharan Africa Department Multilateral Investment Guarantee Agency Sub-Saharan Africa Department Public Disclosure Authorized WORLD BANK GROUP IBRD IFC Regional Vice President: Makhtar Diop : Vice President: Dimitris Tsitsiragos Country Director: Soukeyna Kane Director: Vera Songwe : Country Manager: Rachidi Radji Country Manager: Cassandra Colbert Task Manager: Ali Zafar : Resident Representative: Olivier Buyoya Co-Task Manager: Yele Batana ii LIST OF ACRONYMS AGCP Guinean Central Procurement Agency ANASA Agence Nationale des Statistiques Agricoles (National Agricultural Statistics Agency) Agence de Promotion des Investissements et des Grands Travaux (National Agency for APIX Promotion of Investment and Major Works) BCRG Banque Centrale de la République de Guinée (Central Bank of Guinea) CEQ Commitment to Equity CGE Computable General Equilibrium Conseil National pour la Démocratie et le Développement (National Council for CNDD Democracy and Development) Confédération Nationale des Travailleurs de Guinée (National Confederation of CNTG Workers of Guinea) CPF Country Partnership Framework CPIA Country Policy and Institutional Assessment CRG Crédit Rural de Guinée (Rural Credit of Guinea) CWE China Water and -

Occasional Paper No. 1576 RURAL

Economics and Sociology· Occasional Paper No. 1576 RURAL HOUSEHOLD FINANCE IN THE KINDIA AND NZEREKORE REGIONS OF GUINEA Report submitted to the World Council of Credit Unions by Carlos E. Cuevas Assistant Professor Department of Agricultural Economics and Rural Sociology The Ohio State University j March 1989 TABLE OF CONTENTS page I. INTRODUCTION 1 II. METHODS OF DATA COLLECTION 1 III. OVERVIEW OF THE SAMPLE 3 IV. RURAL HOUSEHOLD INCOME AND FARM PHYSICAL ASSETS 4 V. RURAL HOUSEHOLD FINANCE 7 VI. CONCLUDING REMARKS 9 TEXT TABLES 11 APPENDIX A - Appendix Tables 20 APPENDIX B - Survey Questionnaire 23 2 village. In each village, households were selected at random from available population records. Survey Questionnaire and Complementary Information The questionnaire designed by the author for this study emphasized the gathering of information regarding access to financial services by the rural household, and about the conditions and quality of these services. The issues addressed by the questionnaire can be outlined as follows 1 : - General information about the household and the respondent (Section I of the questionnaire). - Occupation of household members and sources of revenue (Section II). - Agricultural activity, asset position of the household, and selected socio-economic indicators (Sections III and IV). - Access to financial services (loans and deposits) by the head of the household, terms and conditions of these services, and costs incurred in making use of the services (Sections V, VI, and VII). These included the activity of the head of the household in both the formal and the informal financial markets. The provision of informal loans by the head of the household was also documented through a set of questions in Section V of the questionnaire. -

International Union for Conservation of Nature

International Union for Conservation of Nature Country: Guinea Bissau PROJECT DOCUMENT Protection and Restoration of Mangroves and productive Landscape to strengthen food security and mitigate climate change BRIEF DESCRIPTION OF THE PROJECT Mangrove ecosystems cover a major part of the Bissau-Guinean coastal zone and the services they provide to the local population are extremely valuable. However, these ecosystems are at risk and face several challenges. In the past, many mangrove areas were turned into rice fields by the local population. During the independence war of Guinea Bissau (1963-1974), many of these mangrove rice fields were abandoned but they were never restored, leading to both mangrove natural habitat and land degradation, and their respective impacts in terms of loss of biodiversity, decrease in natural productivity and local food insecurity. In response to the above challenges, the objective of the proposed project is to “support the restoration and rehabilitation of degraded mangroves ecosystems functionality and services for enhanced food security and climate change mitigation”. The overall strategy is built around policy influence and knowledge sharing which will lead to replication and scaling up of the approaches and results. It is structured into four components. The first component will support knowledge-based policy development and adoption that promotes mangrove and forests restoration. The second component of the project, promoting a participatory land use planning and management approach at the landscape level, focuses on the restoration and rehabilitation of degraded land in mangrove areas. The third component will contribute to improving the institutional and financial context of mangroves and forests restoration in Guinea Bissau. -

Guinea Staple Food Market Fundamentals March 2017

GUINEA STAPLE FOOD MARKET FUNDAMENTALS MARCH 2017 This publication was produced for review by the United States Agency for International Development. It was prepared by Chemonics International Inc. for the Famine Early Warning Systems Network (FEWS NET), contract number AID-OAA-I-12-00006. The authors’ views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Agency for International Development or the United States government. FEWS NET Guinea Staple Food Market Fundamentals 2017 About FEWS NET Created in response to the 1984 famines in East and West Africa, the Famine Early Warning Systems Network (FEWS NET) provides early warning and integrated, forward-looking analysis of the many factors that contribute to food insecurity. FEWS NET aims to inform decision makers and contribute to their emergency response planning; support partners in conducting early warning analysis and forecasting; and provide technical assistance to partner-led initiatives. To learn more about the FEWS NET project, please visit http://www.fews.net Disclaimer This publication was prepared under the United States Agency for International Development Famine Early Warning Systems Network (FEWS NET) Indefinite Quantity Contract, AID-OAA-I-12-00006. The authors’ views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Agency for International Development or the United States government. Acknowledgements FEWS NET gratefully acknowledges the network of partners in Guinea who contributed their time, analysis, and data to make this report possible. See the list of participating organizations in Annex 2. Market Fundamentals Workshop Participants. Famine Early Warning Systems Network i FEWS NET Guinea Staple Food Market Fundamentals 2017 Table of Contents Executive Summary .................................................................................................................................................................... -

Rhipicephalus Microplus and Its Vector-Borne Haemoparasites in Guinea: Further Species Expansion in West Africa

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.11.12.376426; this version posted November 13, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-ND 4.0 International license. RHIPICEPHALUS MICROPLUS AND ITS VECTOR-BORNE HAEMOPARASITES IN GUINEA: FURTHER SPECIES EXPANSION IN WEST AFRICA Makenov MT1, Toure AH2, Korneev MG3, Sacko N4, Porshakov AM3, Yakovlev SA3, Radyuk EV1, Zakharov KS3, Shipovalov AV5, Boumbaly S4, Zhurenkova OB1, Grigoreva YaE1, Morozkin ES1, Fyodorova MV1, Boiro MY2, Karan LS1 1 – Central Research Institute of Epidemiology, Moscow, Russia 2 – Research Institute of Applied Biology of Guinea, Kindia, Guinea 3 – Russian Research Anti-Plague Institute «Microbe», Saratov, Russia 4 – International Center for Research of Tropical Infections in Guinea, N’Zerekore, Guinea 5 – State Research Center of Virology and Biotechnology «Vector», Kol’tsovo, Russia ABSTRACT Rhipicephalus microplus is an ixodid tick with a pantropical distribution that represents a serious threat to livestock. West Africa was free of this tick until 2007, when its introduction into Benin was reported. Shortly thereafter, the further invasion of this tick into West African countries was demonstrated. In this paper, we describe the first detection of R. microplus in Guinea and list the vector-borne haemoparasites that were detected in the invader and indigenous Boophilus species. In 2018, we conducted a small-scale survey of ticks infesting cattle in three administrative regions of Guinea: N`Zerekore, Faranah, and Kankan. The tick species were identified by examining their morphological characteristics and by sequencing their COI gene and ITS-2 gene fragments. -

Citizens' Involvement in Health Governance

CITIZENS’ INVOLVEMENT IN HEALTH GOVERNANCE (CIHG) Endline Data Collection Final Report September 2020 This report was prepared with funds provided by the U.S. Agency for International Development under Cooperative Agreement AID-675-LA-17-00001. The opinions expressed herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the U.S. Agency for International Development. Contents Executive Summary ...................................................................................... 1 I. Introduction ............................................................................................... 5 Overview ...................................................................................................... 5 Background................................................................................................... 5 II. Methodology ............................................................................................ 6 Approach ...................................................................................................... 6 Data Collection ............................................................................................. 7 Analysis ....................................................................................................... 10 Limitations .................................................................................................. 10 Safety and Security ..................................................................................... 11 III. Findings ................................................................................................ -

Livelihood Zone Descriptions: Guinea

REVISION OF THE LIVELIHOODS ZONE MAP AND DESCRIPTIONS FOR THE REPUBLIC OF GUINEA A REPORT OF THE FAMINE EARLY WARNING SYSTEMS NETWROK (FEWS NET) November 2016 This report is based on the original livelihoods zoning report of 2013 and was produced by Julius Holt, Food Economy Group, consultant to FEWS NET GUINEA Livelihood Zone Map and Descriptions November 2016 2013 Table of Contents Acknowledgements ..................................................................................................................................................... 3 Introduction ................................................................................................................................................................. 4 Methodology ................................................................................................................................................................ 4 Changes to the Livelihood Zones Map ...................................................................................................................... 5 The National Context ................................................................................................................................................. 6 Livelihood Zone Descriptions .................................................................................................................................. 10 ZONE GN01 LITTORAL: RICE, FISHING, PALM OIL .................................................................................................................................................