Guinea Staple Food Market Fundamentals March 2017

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Région De Kindia 2018

REPUBLIQUE DE GUINEE Travail - Justice- Solidarité MINISTERE DU PLAN ET DU DEVELOPPEMENT ECONOMIQUE La région de Kindia en chiffres Edition 2020 GEOGRAPHIE ET ORGANISATION ADMINISTRATIVE Géographie 0rganisation administrative en 2018 5 préfectures ; 41 sous-préfectures ; 5 communes urbaines, Superficie = 28 875 km2 627 quartiers/districts ; 2 424 secteurs 40 communes rurales Source : BSD Ministère de l’administration du territoire et de la décentralisation (Annuaire statistique 2018) Préfectures Sous-préfectures Bangouyah, Damankanyah, Friguiagbé, Kolente, Lisan, Madina Oula, Mambiya, Molota, Kindia Samayah, Sougueta Coyah Kouriya, Manéah, Wonkifong, Dubréka Badi, Falessade, Khorira, Ouassou, Tanènè, Tondon, Forécariah Alassoya, Benty, Farmoriah, Kaback, Kakossa, Kallia, Maferenya, Moussaya, Sikhourou Bourouwal, Daramagnaky, Gououdje, Koba, Kollet, Kosotamy, Missira, Santou, Sarekaly, Sinta, Télimélé Sogolon, Tarihoye, Thionthian Source : BSD Ministère de l’administration du territoire et de la décentralisation (Annuaire statistique 2018) STATISTIQUES DEMOGRAPHIQUES Populations des RGPH 1983 1996 2014 Population région de Kindia 555 937 928 312 1 561 336 Population de la principale préfecture : Kindia 163 032 287 611 439 614 Part de la population nationale en 2014 : 14.8 % Rang régional en 2014 : 4/8 Sources : Institut national de la statistique/RGPH Population au 1er juillet 2015 2016 2017 2018 Population région Kindia 1 620 881 1 667 695 1 715 504 1 764 268 Sources : Institut national de la statistique (Perspectives démographiques de -

JPC.CCP Bureau Du Prdsident

Onchoccrciasis Control Programmc in the Volta Rivcr Basin arca Programme de Lutte contre I'Onchocercose dans la R6gion du Bassin de la Volta JOIN'T PROCRAMME COMMITTEE COMITE CONJOINT DU PROCRAMME Officc of the Chuirrrran JPC.CCP Bureau du Prdsident JOINT PROGRAII"IE COMMITTEE JPC3.6 Third session ORIGINAL: ENGLISH L Bamako 7-10 December 1982 October 1982 Provisional Agenda item 8 The document entitled t'Proposals for a Western Extension of the Prograncne in Mali, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Ssnegal and Sierra Leone" was reviewed by the Corrrittee of Sponsoring Agencies (CSA) and is now transmitted for the consideration of the Joint Prograurne Conrnittee (JPC) at its third sessior:. The CSA recalls that the JPC, at its second session, following its review of the Feasibility Study of the Senegal River Basin area entitled "Senegambia Project : Onchocerciasis Control in Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, l,la1i, Senegal and Sierra Leone", had asked the Prograrrne to prepare a Plan of Operations for implementing activities in this area. It notes that the Expert Advisory Conrnittee (EAC) recormnended an alternative strategy, emphasizing the need to focus, in the first instance, on those areas where onchocerciasis was hyperendemic and on those rivers which were sources of reinvasion of the present OCP area (Document JPC3.3). The CSA endorses the need for onchocerciasis control in the Western extension area. However, following informal consultations, and bearing in mind the prevailing financial situation, the CSA reconrnends that activities be implemented in the area on a scale that can be managed by the Prograrmne and at a pace concomitant with the availability of funds, in order to obtain the basic data which have been identified as missing by the proposed plan of operations. -

The Lost & Found Children of Abraham in Africa and The

SANKORE' Institute of Islamic - African Studies International The Lost & Found Children of Abraham In Africa and the American Diaspora The Saga of the Turudbe’ Fulbe’ & Their Historical Continuity Through Identity Construction in the Quest for Self-Determination by Abu Alfa Umar MUHAMMAD SHAREEF bin Farid 0 Copyright/2004- Muhammad Shareef SANKORE' Institute of Islamic - African Studies International www.sankore.org/www,siiasi.org All rights reserved Cover design and all maps and illustrations done by Muhammad Shareef 1 SANKORE' Institute of Islamic - African Studies International www.sankore.org/ www.siiasi.org ﺑِ ﺴْ ﻢِ اﻟﻠﱠﻪِ ا ﻟ ﺮﱠ ﺣْ ﻤَ ﻦِ ا ﻟ ﺮّ ﺣِ ﻴ ﻢِ وَﺻَﻠّﻰ اﻟﻠّﻪُ ﻋَﻠَﻲ ﺳَﻴﱢﺪِﻧَﺎ ﻣُ ﺤَ ﻤﱠ ﺪٍ وﻋَﻠَﻰ ﺁ ﻟِ ﻪِ وَ ﺻَ ﺤْ ﺒِ ﻪِ وَ ﺳَ ﻠﱠ ﻢَ ﺗَ ﺴْ ﻠِ ﻴ ﻤ ﺎً The Turudbe’ Fulbe’: the Lost Children of Abraham The Persistence of Historical Continuity Through Identity Construction in the Quest for Self-Determination 1. Abstract 2. Introduction 3. The Origin of the Turudbe’ Fulbe’ 4. Social Stratification of the Turudbe’ Fulbe’ 5. The Turudbe’ and the Diffusion of Islam in Western Bilad’’s-Sudan 6. Uthman Dan Fuduye’ and the Persistence of Turudbe’ Historical Consciousness 7. The Asabiya (Solidarity) of the Turudbe’ and the Philosophy of History 8. The Persistence of Turudbe’ Identity Construct in the Diaspora 9. The ‘Lost and Found’ Turudbe’ Fulbe Children of Abraham: The Ordeal of Slavery and the Promise of Redemption 10. Conclusion 11. Appendix 1 The `Ida`u an-Nusuukh of Abdullahi Dan Fuduye’ 12. Appendix 2 The Kitaab an-Nasab of Abdullahi Dan Fuduye’ 13. -

Etc Status with 21Confcase 1.Pdf

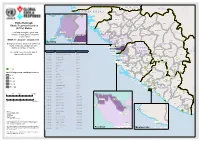

SE N E G A L M A L I GU IN EA -B IS SA U Koundara Mali ETC"-GIN-003 Koubia Gaoual Lelouma Dinguiraye Siguiri Ebola Outbreak: Labe Tougue Ebola Treatment Centres Telimele (ETCs) Status Dalaba Kouroussa Boke This Map shows the status and ETC"-GIN-012 Pita Mandiana Boffa Dabola location of each Ebola Treatment Mamou Fria Center (ETC). ETC"-GIN-001 ETC"-GIN-018 Dubreka Kindia Faranah ETC-GIN-015 WEEK 17: 20 April - 26 April 2015 " Kankan Conakry Copyright:© 2014 Esri Background colour show new confirmed Koinadugu ETC-GIN-00C3 oyah G U I N E A " Bombali cases for the last 21 days for each ConakryETC-GIN-012 district, prefecture or county. ETC"-EGT"ICN"-G00IN1-018 S I E R R A Kissidougou CÔ TE ETC-GIN-017 ETC CODE Site Name Country Forecariah " L E O N E Kerouane D' IV OI R E The number over the ETC sign is ETC-GIN-001 Conakry Region Guinea Beyla Freetownreferenced in the table. ETC-GIN-003 Kindia Region, Coyah Prefecture Guinea Kambia ETC"-SLE-034 ETC-SLE-008 ETC-GIN-007 Nzérékoré Region Guinea " Kono Gueckedou ETC-GIN-009 Nzérékoré Region Guinea Port Loko EETTCC--SSLLEE--00002571 ETC-SLE-022 "" " ETC-GIN-009 ETC-GIN-010 Nzérékoré Region Guinea ETC-SLE-031 " " ETC-GIN-010 Western " ETC-GIN-011 ETC-GIN-011 Nzérékoré Region Guinea Area Urban ETECT-SCL-SEL-0E2-4028 Tonkolili " ETC-LBR-011 ETC-GIN-012 Conakry Region Guinea "E"ETTC"C--SSLLEE--00121375 ETECT"-CS-LSEL-E0-2303226 " ETC-GIN-015 Kindia Guinea ET"C"-SLE-0116 Lofa Macenta Western " " ETC-SLE-009 ETC-GIN-017 Forecariah Guinea Area Rural " ETC-GIN-018 Conakry Guinea ETC-SLE-004 Nzerekore -

Are the Fouta Djallon Highlands Still the Water Tower of West Africa?

water Article Are the Fouta Djallon Highlands Still the Water Tower of West Africa? Luc Descroix 1,2,*, Bakary Faty 3, Sylvie Paméla Manga 2,4,5, Ange Bouramanding Diedhiou 6 , Laurent A. Lambert 7 , Safietou Soumaré 2,8,9, Julien Andrieu 1,9, Andrew Ogilvie 10 , Ababacar Fall 8 , Gil Mahé 11 , Fatoumata Binta Sombily Diallo 12, Amirou Diallo 12, Kadiatou Diallo 13, Jean Albergel 14, Bachir Alkali Tanimoun 15, Ilia Amadou 15, Jean-Claude Bader 16, Aliou Barry 17, Ansoumana Bodian 18 , Yves Boulvert 19, Nadine Braquet 20, Jean-Louis Couture 21, Honoré Dacosta 22, Gwenaelle Dejacquelot 23, Mahamadou Diakité 24, Kourahoye Diallo 25, Eugenia Gallese 23, Luc Ferry 20, Lamine Konaté 26, Bernadette Nka Nnomo 27, Jean-Claude Olivry 19, Didier Orange 28 , Yaya Sakho 29, Saly Sambou 22 and Jean-Pierre Vandervaere 30 1 Museum National d’Histoire Naturelle, UMR PALOC IRD/MNHN/Sorbonne Université, 75231 Paris, France; [email protected] 2 LMI PATEO, UGB, St Louis 46024, Senegal; [email protected] (S.P.M.); [email protected] (S.S.) 3 Direction de la Gestion et de la Planification des Ressources en Eau (DGPRE), Dakar 12500, Senegal; [email protected] 4 Département de Géographie, Université Assane Seck de Ziguinchor, Ziguinchor 27000, Senegal 5 UFR des Sciences Humaines et Sociales, Université de Lorraine, 54015 Nancy, France 6 Master SPIBES/WABES Project (Centre d’Excellence sur les CC) Bingerville, Université Félix Houphouët Boigny, 582 Abidjan 22, Côte d’Ivoire; [email protected] 7 Doha Institute for Graduate Studies, -

A VISION of WEST AFRICA in the YEAR 2020 West Africa Long-Term Perspective Study

Millions of inhabitants 10000 West Africa Wor Long-Term Perspective Study 1000 Afr 100 10 1 Yea 1965 1975 1850 1800 1900 1950 1990 2025 2000 Club Saheldu 2020 % of the active population 100 90 80 AGRICULTURAL SECTOR 70 60 50 40 30 NON AGRICULTURAL “INFORMAL” SECTOR 20 10 NON AGRICULTURAL 3MODERN3 SECTOR 0 1960 1970 1980 1990 2000 2010 2020 Preparing for 2020: 6 000 towns of which 300 have more than 100 000 inhabitants Production and total availability in gigaczalories per day Import as a % of availa 500 the Future 450 400 350 300 250 200 A Vision of West Africa 150 100 50 0 1961 1963 1965 1967 1969 1971 1973 1975 1977 1979 1981 1983 1985 1987 1989 1991 Imports as a % of availability Total food availability Regional production in the Year 2020 2020 CLUB DU SAHEL PREPARING FOR THE FUTURE A VISION OF WEST AFRICA IN THE YEAR 2020 West Africa Long-Term Perspective Study Edited by Jean-Marie Cour and Serge Snrech ORGANISATION FOR ECONOMIC CO-OPERATION AND DEVELOPMENT ○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○ FOREWoRD ○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○ In 1991, four member countries of the Club du Sahel: Canada, the United States, France and the Netherlands, suggested that a regional study be undertaken of the long-term prospects for West Africa. Several Sahelian countries and several coastal West African countries backed the idea. To carry out this regional study, the Club du Sahel Secretariat and the CINERGIE group (a project set up under a 1991 agreement between the OECD and the African Development Bank) formed a multi-disciplinary team of African and non-African experts. -

Guinea Ebola Response International Organization for Migration

GUINEA EBOLA RESPONSE INTERNATIONAL ORGANIZATION FOR MIGRATION SITUATION REPORT From 21 January to 4 February, 2016 News Training of 11 trainer-workers in Health Emergency Management at IOM’s office in Conakry. © IOM 2016 On 18 January, IOM took part to a cross- From January 25 to 29, in partnership On 28 January, the Chief of Mission of IOM border meeting in Pamelap with the Minister of with CDC and the George Washington Guinea, along with UNCT delegation, Health, the National Coordination, as well as EVD University, IOM organized a training of congratulated the newly appointed Prime Response partners in Guinea and Sierra Leone, trainer session in Health Emergency Minister, Head of Government, Mr. Mamadi to share all information related to the EVD cases Management (HEM) to 11 beneficiaries. Youla, for his nomination and addressed him in Sierra Leone. their wishes. Situation of the Ebola Virus Disease after its resurgence in Sierra Leone On January 20, a second Ebola Virus Disease (EVD) case was confirmed in Sierra Leone. It concerned the aunt of the young lady who died on January 12 in the district of Tonkolili, in the northern part of the country and that post-mortem analysis confirmed that she died of EVD. After the Ebola Virus Disease reappeared in Sierra Leone on January 14, Guinean authorities decided to strengthen health surveillance activities at the country’s borders with Sierra Leone. IOM remains a key partner in implementing these activities. OIM re-launched health screening activities at the 48 official and non-official Points of Entry along the border in Forecariah and Kindia (Madina Oula). -

Recipient UN Organization(S): UNICEF UNDP Proposal Contacts

EBOLA RESPONSE MULTI-PARTNER TRUST FUND PROPOSAL Proposal Title: Stop Ebola through social Recipient UN Organization(s): mobilization and community engagement in Guinea UNICEF UNDP Proposal Contacts: Implementing Partner(s) – name & type For UNICEF (Government, CSO, etc.): Dr Mohamed Ayoya - NGOs: Plan Guinée, CERAD, Resident Representative CENAFOD, CNOSCG; youth Address: UNICEF, Corniche, Coleah, Conakry organizations Telephone: +224 622 663 452 - Government. E-mail: [email protected] For UNDP Aissatou Cisse-Yao Yao Deputy Country Director, Programme Address:UNDP Guinée Maison Commune Coléah Commune de Matam BP : 222 Conakry République de Guinée Telephone: 224 622 35 54 69 E-mail: [email protected] Proposal Location (country): Proposal Location (provinces): Please select one from the following Conakry, Boke, Kindia, Mamou, Faranah, Guinea Kankan, Nzerekore. Liberia (see map in Annex for detailed targets locations) Sierra Leone Common Services Project Description: Requested amount: One sentence describing the project’s scope and focus. USD 3,139,364 UNICEF USD 809,000 UNDP Through social mobilization, with a particular focus on Total requested amount: USD 3,948,364 vulnerable and at-risk groups such as women and youth, UNICEF and UNDP will support communities Other sources of funding of this proposal: to setup Community Watch Committees (CWCs), UNICEF regular resources door-to-door sensitization and referral of Ebola UNDP core fund suspected and contact cases. UNMEER budget: Other sources (indicate): Government Input: in kind support 1 Start Date: 10 December 2014 End Date: 15 June 2015 Total duration (in months): 6 months MISSION CRITICAL ACTIONS to which the proposal is contributing. For reporting purposes, each project should contribute to one SO. -

PRADD II Guinea Impact Evaluation Design Report

EVALUATION, RESEARCH AND COMMUNICATION (ERC) Property Rights and Artisanal Diamond Development Project II (PRADD II) Impact Evaluation Design Report AUGUST 2014 This document was produced for review by the United States Agency for International Development. It was prepared by Cloudburst Consulting Group, Inc. for the Evaluation, Research, and Communication (ERC) Task Order under the Strengthening Tenure and Resource Rights (STARR) IQC. Written and prepared by Heather Huntington, Michael McGovern, and Darrin Christensen. Prepared for the United States Agency for International Development, USAID Contract Number AID- OAA-TO-13-00019, Evaluation, Research and Communication (ERC) Task Order under Strengthening Tenure and Resource Rights (STARR) IQC No. AID-OAA-I-12-00030. Implemented by: Cloudburst Consulting Group, Inc. 8400 Corporate Drive, Suite 550 Landover, MD 20785-2238 EVALUATION, RESEARCH AND COMMUNICATION (ERC) Property Rights and Artisanal Diamond Development Project II (PRADD II) Impact Evaluation Design Report AUGUST 2014 DISCLAIMER The authors' views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Agency for International Development or the United States Government. CONTENTS 36T36TCONTENTS36T36T ............................................................................................................................ 4 36T36TACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS36T36T ..................................................................................... 5 36T36T1.0 INTRODUCTION36T36T .............................................................................................................. -

Appraisal Report Kankan-Kouremale-Bamako Road Multinational Guinea-Mali

AFRICAN DEVELOPMENT FUND ZZZ/PTTR/2000/01 Language: English Original: French APPRAISAL REPORT KANKAN-KOUREMALE-BAMAKO ROAD MULTINATIONAL GUINEA-MALI COUNTRY DEPARTMENT OCDW WEST REGION JANUARY 1999 SCCD : N.G. TABLE OF CONTENTS Page PROJECT INFORMATION BRIEF, EQUIVALENTS, ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS, LIST OF ANNEXES AND TABLES, BASIC DATA, PROJECT LOGICAL FRAMEWORK, ANALYTICAL SUMMARY i-ix 1 INTRODUCTION.............................................................................................................. 1 1.1 Project Genesis and Background.................................................................................... 1 1.2 Performance of Similar Projects..................................................................................... 2 2 THE TRANSPORT SECTOR ........................................................................................... 3 2.1 The Transport Sector in the Two Countries ................................................................... 3 2.2 Transport Policy, Planning and Coordination ................................................................ 4 2.3 Transport Sector Constraints.......................................................................................... 4 3 THE ROAD SUB-SECTOR .............................................................................................. 5 3.1 The Road Network ......................................................................................................... 5 3.2 The Automobile Fleet and Traffic................................................................................. -

Guinea : Reference Map of Kankan Region (As of 3 March 2015)

Guinea : Reference Map of Kankan Region (as of 3 March 2015) Bankolen Mambifagalena Niagassola Kry Tourelen Berlen Sokoromansa Magadiano Faraboloni Linkekoro KIGNEKOUROU CENTRE Bouyido Malsadou Seourou Konfara 2 Gnembou Tanssa Magnaka KOTE CENTRE Balenda SOUMBARAYA CENTRE Kourelen TALABE CENTRE Dialawassa II Kondoko Djanwely Itipony Dougounta Dora Kourakoda DIBIA CENTRE Djinko Ilimalo Naboun Kanimbakalako Kodougoulen KAKAMA CENTRE Tondo Komagron Kayaga Kignedi Sininko Kadabili Kignero Gnere Sininkoro Badamako Kounsounkoro Yirikelèma Kanikoumbaya SOKORO CENTRE DIATEA CENTRE Dita Salla Tondji1 Koda Kebesabaya Siguirini Sakounou Malea Bembéta Megnèkoma Silabado Diakan Toukönö BOULAN CENTRE Gbèdela MANKADIAN CENTRE Gbörökola Doko Tombani Maragbè Kana Sékela Mansadji Sidao Tonso Banankölö Tomba Doula Amina Amina Kinièba Franwalia Tinko Diatifere Fountou Soumbalakölen Iroda Kounkoun Koda Mainou SARAYA CENTRE Tomboni Sinimbaya KOBEDRA CENTRE MIGNADA CENTRE Bökökö Farani Banora Simbona Bida Tomba Boufe Bandioula FOULATA CENTRE Kintinian Yorola Tougnou Sanouna SEELA CENTRE Bankon MALI Tinkoba Kobada Beretela Sando Noumandiana Kandani Fodela Bèrèko Tabakoro BAMBALA Tabako Madila Moyafara Kourouni Banantamou Siguiri FALAMA BANFARA CENTRE Saint Alexis Dialakoro Nedekoroko Banantou Lansanaya Sakolado Manakoro Farabada Dounin Farabelen Bida Bantambaye Woléwoléya Koda Koda Kogne Tambabougou Gbongoroma Kigne Kokoudouninda Dinguiraye Gbilin Balandougouba KONKOYE CENTRE Waran-Fougou Kiniebakoura DIARRADOU CENTRE Sansani Faradjian Tassiliman Centre Kewoulé -

Observing the 2010 Presidential Elections in Guinea

Observing the 2010 Presidential Elections in Guinea Final Report Waging Peace. Fighting Disease. Building Hope. Map of Guinea1 1 For the purposes of this report, we will be using the following names for the regions of Guinea: Upper Guinea, Middle Guinea, Lower Guinea, and the Forest Region. Observing the 2010 Presidential Elections in Guinea Final Report One Copenhill 453 Freedom Parkway Atlanta, GA 30307 (404) 420-5188 Fax (404) 420-5196 www.cartercenter.org The Carter Center Contents Foreword ..................................1 Proxy Voting and Participation of Executive Summary .........................2 Marginalized Groups ......................43 The Carter Center Election Access for Domestic Observers and Observation Mission in Guinea ...............5 Party Representatives ......................44 The Story of the Guinean Security ................................45 Presidential Elections ........................8 Closing and Counting ......................46 Electoral History and Political Background Tabulation .............................48 Before 2008 ..............................8 Election Dispute Resolution and the From the CNDD Regime to the Results Process ...........................51 Transition Period ..........................9 Disputes Regarding First-Round Results ........53 Chronology of the First and Disputes Regarding Second-Round Results ......54 Second Rounds ...........................10 Conclusion and Recommendations for Electoral Institutions and the Framework for the Future Elections ...........................57