Chapter 2: Conakry

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Guinea Smoking Prevalence Tobacco Economy

GUINEA AFRICAN REGION Population (millions) Real GDP per capita (PPP), US Dollars 1995 2000 2025 2050 1975 1157 All adults, ages 15+ 4.039 4.562 8.697 15.290 1980 1230 Female adults 2.023 2.280 4.319 7.596 1985 1319 1990 1424 All youth, ages 0-14 3.293 3.592 5.423 5.421 1995 1431 Female youth 1.626 1.772 2.669 2.672 2000 1564 Source: United Nations Population Division, World Population Prospects 1950-2050 (2000 revision) Source: World Health Report 2002 SMOKING PREVALENCE Adult (11-72 Year Olds) Youth Health Professionals Males 58.9 Males – Males – Females 47.3 Females – Females – Overall 57.6 Overall – Overall – Adult: Current smoking in five districts of the capital city of Conakry (Dixinn, Kaloum, Matam, Matoto and Ratoma), study does not claim to be representative of the Guinean population (survey year unknown); Ngom, A., Dieng, B. and Bangoura, M. (1998). Investigation of nicotine addiction in Guinea. Conakry: Department of Health and Office of WHO in Guinea. Youth: No data available Health professional: No data available TOBACCO ECONOMY Annual per capita Consumption, Three Year Moving Average Annual Cigarette Consumption Per capita Consumption Total Consumption Year (cigarette sticks) (millions of cigarette sticks) Level of cigarette 1970 –– consumption No data available 1980 –– 1990 –– 1995 –– 2000 –– 1970 1980 1990 2000 Annual Tobacco Trade and Agriculture Statistics Unit of Measurement 1970 1980 1990 1995 2000 Cigarette imports sticks in millions –––2809 8390 Cigarette exports sticks in millions –––723 Tobacco leaf imports metric -

Official History, Popular Memory: Reconfiguration of the African Past in the Films of Ousmane Sembene Mbye Cham Howard University

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Contributions in Black Studies A Journal of African and Afro-American Studies Volume 11 Ousmane Sembène: Dialogues with Critics Article 4 & Writers September 2008 Official History, Popular Memory: Reconfiguration of the African Past in the Films of Ousmane Sembene Mbye Cham Howard University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/cibs Recommended Citation Cham, Mbye (2008) "Official History, Popular Memory: Reconfiguration of the African Past in the Films of Ousmane Sembene," Contributions in Black Studies: Vol. 11 , Article 4. Available at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/cibs/vol11/iss1/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Afro-American Studies at ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Contributions in Black Studies by an authorized editor of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Cham: Official History, Popular Memory Official History, Popular Memory: Reconfiguration of the African Past in the Films of Ousmane Sembene by Mbye Cham Howard University I would like to begin my presentation by quoting the words ofa grioL His name is Diali Mamadou Kouyat.e; he performed the Sundiata epic, which has been ttanscribed by Djibril Tamsir Niane. The griot starts his performance with these words: I am a griot. .. we are the vessels ofspeech, we are the repositories which harbor secrets many centuries old The artofeloquence has no secrets for us; without us, the names ofkings would vanish into oblivion, we are the memory ofmankind...Historyhas no mystery for us...for it is we who keep the keys to the twelve doors of Mali. -

Actuelle De L'ifri

AAccttuueellllee ddee ll’’IIffrrii ______________________________________________________________________ Africa in Questions No. 20 Fragility Factors and Reconciliation Needs in Forest Guinea ______________________________________________________________________ Beatrice Bianchi March 2015 . Sub-Saharan Africa Program The Institut français des relations internationales (Ifri) is a research center and a forum for debate on major international political and economic issues. Headed by Thierry de Montbrial since its founding in 1979, Ifri is a non- governmental and a non-profit organization. As an independent think tank, Ifri sets its own research agenda, publishing its findings regularly for a global audience. Using an interdisciplinary approach, Ifri brings together political and economic decision-makers, researchers and internationally renowned experts to animate its debate and research activities. With offices in Paris and Brussels, Ifri stands out as one of the rare French think tanks to have positioned itself at the very heart of European debate. The views expressed herein are those of the authors. © All rights reserved, Ifri, 2015 Ifri Ifri-Bruxelles 27, rue de la Procession Rue Marie-Thérèse, 21 75740 Paris Cedex 15 – FRANCE 1000 – Bruxelles – BELGIUM Tél. : +33 (0)1 40 61 60 00 Tél. : +32 (0)2 238 51 10 Fax : +33 (0)1 40 61 60 60 Fax : +32 (0)2 238 51 15 Email : [email protected] Email : [email protected] Website : Ifri.org 1 © Ifri Beatrice Bianchi / Fragility Factors and Reconciliation Needs in Forest Guinea Introduction In December 2013 the first Ebola cases surfaced in Guéckedou district, near the Liberian and Sierra Leon borders in the Forest Region of Guinea. The outbreak quickly spread from Forest Guinea to the rest of the country and, through the borders, to neighbouring countries. -

IOM Guinea Ebola Response Situation Report, 8-31 March 2016

GUINEA EBOLA RESPONSE INTERNATIONAL ORGANIZATION FOR MIGRATION RAPPORT DE SITUATION From 8 to 31, March 2016 News Launching of the “soft ring containment” of Koropara sub-prefecture. © IOM Guinea 2016 On February 29 and March 17, three On March 9, 2016, IOM organized a From March 9 to 11, 2016, a joint IOM-RTI- people died in the sub-prefecture of ceremony during which, it officially handed- DPS mission went to different sub- Koropara following an unknown disease over the health post of Kamakouloun to sub- prefectures of Boffa for a maiden contact characterized by fever, deep emaciation, prefectural authorities of Kamsar, prefecture with local authorities. The aim was to explain diarrhea including vomiting of blood. A few of Boke. The health facility was rehabilitated the criteria used in the selection of CHA days later, two other people developed the and fully equipped by the organization. (Community Health Assistants), validating the same symptoms. The tests, carried out on list of CHA provided by the DPS in their March 17, were positive to the Ebola Virus localities and selecting 30 participants for the Disease, indicating the resurgence of the participatory mapping exercise (10 wise men, disease in Guinea, nearly three months after 10 youths and 10 women). it was officially declared over by WHO. Situation of the Ebola virus disease after its resurgence in Guinea In the sub-prefecture of Koropara, located at 97km from the city of NZerekore, an approximately 50-year-old farmer along with his two wives died between February 29 and March 17, 2016 following an unknown disease characterized by fever, deep emaciation, diarrhea and vomiting of blood. -

Guinea Ebola Response International Organization for Migration

GUINEA EBOLA RESPONSE INTERNATIONAL ORGANIZATION FOR MIGRATION RAPPORT DE SITUATION From 8 to 31, March 2016 News Launching of the “soft ring containment” of Koropara sub-prefecture. © IOM Guinea 2016 On February 29 and March 17, three On March 9, 2016, IOM organized a From March 9 to 11, 2016, a joint IOM-RTI- people died in the sub-prefecture of ceremony during which, it officially handed- DPS mission went to different sub- Koropara following an unknown disease over the health post of Kamakouloun to sub- prefectures of Boffa for a maiden contact characterized by fever, deep emaciation, prefectural authorities of Kamsar, prefecture with local authorities. The aim was to explain diarrhea including vomiting of blood. A few of Boke. The health facility was rehabilitated the criteria used in the selection of CHA days later, two other people developed the and fully equipped by the organization. (Community Health Assistants), validating the same symptoms. The tests, carried out on list of CHA provided by the DPS in their March 17, were positive to the Ebola Virus localities and selecting 30 participants for the Disease, indicating the resurgence of the participatory mapping exercise (10 wise men, disease in Guinea, nearly three months after 10 youths and 10 women). it was officially declared over by WHO. Situation of the Ebola virus disease after its resurgence in Guinea In the sub-prefecture of Koropara, located at 97km from the city of NZerekore, an approximately 50-year-old farmer along with his two wives died between February 29 and March 17, 2016 following an unknown disease characterized by fever, deep emaciation, diarrhea and vomiting of blood. -

Appraisal Report Kankan-Kouremale-Bamako Road Multinational Guinea-Mali

AFRICAN DEVELOPMENT FUND ZZZ/PTTR/2000/01 Language: English Original: French APPRAISAL REPORT KANKAN-KOUREMALE-BAMAKO ROAD MULTINATIONAL GUINEA-MALI COUNTRY DEPARTMENT OCDW WEST REGION JANUARY 1999 SCCD : N.G. TABLE OF CONTENTS Page PROJECT INFORMATION BRIEF, EQUIVALENTS, ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS, LIST OF ANNEXES AND TABLES, BASIC DATA, PROJECT LOGICAL FRAMEWORK, ANALYTICAL SUMMARY i-ix 1 INTRODUCTION.............................................................................................................. 1 1.1 Project Genesis and Background.................................................................................... 1 1.2 Performance of Similar Projects..................................................................................... 2 2 THE TRANSPORT SECTOR ........................................................................................... 3 2.1 The Transport Sector in the Two Countries ................................................................... 3 2.2 Transport Policy, Planning and Coordination ................................................................ 4 2.3 Transport Sector Constraints.......................................................................................... 4 3 THE ROAD SUB-SECTOR .............................................................................................. 5 3.1 The Road Network ......................................................................................................... 5 3.2 The Automobile Fleet and Traffic................................................................................. -

Observing the 2010 Presidential Elections in Guinea

Observing the 2010 Presidential Elections in Guinea Final Report Waging Peace. Fighting Disease. Building Hope. Map of Guinea1 1 For the purposes of this report, we will be using the following names for the regions of Guinea: Upper Guinea, Middle Guinea, Lower Guinea, and the Forest Region. Observing the 2010 Presidential Elections in Guinea Final Report One Copenhill 453 Freedom Parkway Atlanta, GA 30307 (404) 420-5188 Fax (404) 420-5196 www.cartercenter.org The Carter Center Contents Foreword ..................................1 Proxy Voting and Participation of Executive Summary .........................2 Marginalized Groups ......................43 The Carter Center Election Access for Domestic Observers and Observation Mission in Guinea ...............5 Party Representatives ......................44 The Story of the Guinean Security ................................45 Presidential Elections ........................8 Closing and Counting ......................46 Electoral History and Political Background Tabulation .............................48 Before 2008 ..............................8 Election Dispute Resolution and the From the CNDD Regime to the Results Process ...........................51 Transition Period ..........................9 Disputes Regarding First-Round Results ........53 Chronology of the First and Disputes Regarding Second-Round Results ......54 Second Rounds ...........................10 Conclusion and Recommendations for Electoral Institutions and the Framework for the Future Elections ...........................57 -

21738 Nov. 26—Dec. 3, 1966

21738 KEESING'S CONTEMPORARY ARCHIVES Nov. 26—Dec. 3, 1966 (c) Mr. M. C. Chagla (Education) was appointed External B. ORGANIZATION OF AFRICAN UNITY.—Fourth Affairs Minister ; and (d) Mr. Fakhruddin Ahmed became Assembly of Heads of State and Government. - Dispute Education Minister. between Ghana and Guinea. Mr. Chavan (53) was Chief Minister of Bombay in 1956-60 and The fourth Assembly of the Heads of State and Government Chief Minister of Maharashtra in 1960-62, and succeeded Mr. of the member-States of the Organization of African Unity Krishna Menon as Defence Minister in November 1962, during the (O.A.U.) took place in Addis Ababa on Nov. 5-9. It was border oonfliot with China. Sardar Swaran Singh (69) entered the preceded by a meeting of the Council of Ministers of the Cabinet in 1952, and held a succession of Ministries before becoming External Affairs Minister in 1964. Mr. Chagla (66), a former Chief O.A.U., but this meeting, as well as the Assembly itself, was Justice of the Bombay High Court, was Ambassador in Washington largely overshadowed by a dispute caused by the Government in 1958-62 and High Commissioner in London in 1962-63, and of Ghana in intercepting and detaining the Guinean mission entered the Cabinet as Education Minister in 1963. He is the first to the O.A.U. Moslem to hold the post Of External Affairs Minister. The Ghana-Guinea Dispute. While the Indian press strongly criticized Mrs. Gandhi for her alleged vacillation over the Cabinet changes, the Prime On Oct. 29 the Ghanaian authorities removed from a Pan Minister herself deprecated Mr. -

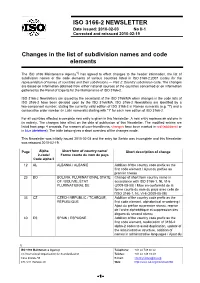

ISO 3166-2 NEWSLETTER Changes in the List of Subdivision Names And

ISO 3166-2 NEWSLETTER Date issued: 2010-02-03 No II-1 Corrected and reissued 2010-02-19 Changes in the list of subdivision names and code elements The ISO 3166 Maintenance Agency1) has agreed to effect changes to the header information, the list of subdivision names or the code elements of various countries listed in ISO 3166-2:2007 Codes for the representation of names of countries and their subdivisions — Part 2: Country subdivision code. The changes are based on information obtained from either national sources of the countries concerned or on information gathered by the Panel of Experts for the Maintenance of ISO 3166-2. ISO 3166-2 Newsletters are issued by the secretariat of the ISO 3166/MA when changes in the code lists of ISO 3166-2 have been decided upon by the ISO 3166/MA. ISO 3166-2 Newsletters are identified by a two-component number, stating the currently valid edition of ISO 3166-2 in Roman numerals (e.g. "I") and a consecutive order number (in Latin numerals) starting with "1" for each new edition of ISO 3166-2. For all countries affected a complete new entry is given in this Newsletter. A new entry replaces an old one in its entirety. The changes take effect on the date of publication of this Newsletter. The modified entries are listed from page 4 onwards. For reasons of user-friendliness, changes have been marked in red (additions) or in blue (deletions). The table below gives a short overview of the changes made. This Newsletter was initially issued 2010-02-03 and the entry for Serbia was incomplete and this Newsletter was reissued 2010-02-19. -

Global Suicide Rates and Climatic Temperature

SocArXiv Preprint: May 25, 2020 Global Suicide Rates and Climatic Temperature Yusuke Arima1* [email protected] Hideki Kikumoto2 [email protected] ABSTRACT Global suicide rates vary by country1, yet the cause of this variability has not yet been explained satisfactorily2,3. In this study, we analyzed averaged suicide rates4 and annual mean temperature in the early 21st century for 183 countries worldwide, and our results suggest that suicide rates vary with climatic temperature. The lowest suicide rates were found for countries with annual mean temperatures of approximately 20 °C. The correlation suicide rate and temperature is much stronger at lower temperatures than at higher temperatures. In the countries with higher temperature, high suicide rates appear with its temperature over about 25 °C. We also investigated the variation in suicide rates with climate based on the Köppen–Geiger climate classification5, and found suicide rates to be low in countries in dry zones regardless of annual mean temperature. Moreover, there were distinct trends in the suicide rates in island countries. Considering these complicating factors, a clear relationship between suicide rates and temperature is evident, for both hot and cold climate zones, in our dataset. Finally, low suicide rates are typically found in countries with annual mean temperatures within the established human thermal comfort range. This suggests that climatic temperature may affect suicide rates globally by effecting either hot or cold thermal stress on the human body. KEYWORDS Suicide rate, Climatic temperature, Human thermal comfort, Köppen–Geiger climate classification Affiliation: 1 Department of Architecture, Polytechnic University of Japan, Tokyo, Japan. -

The Impact of Climate Variability and Conflict on Childhood Diarrhea and Malnutrition in West Africa

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 2-2016 The Impact of Climate Variability and Conflict on Childhood Diarrhea and Malnutrition in West Africa Gillian Dunn Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/765 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] The Impact of Climate Variability and Conflict on Childhood Diarrhea and Malnutrition in West Africa by Gillian Dunn A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Public Health in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Public Health, The City University of New York 2016 © 2016 Gillian Dunn All Rights Reserved ii The Impact of Climate Variability and Conflict on Childhood Diarrhea and Malnutrition in West Africa by Gillian Dunn This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Public Health to satisfy the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Public Health Deborah Balk, PhD Sponsor of Examining Committee Date Signature Denis Nash, PhD Executive Officer, Public Health Date Signature Examining Committee: Glen Johnson, PhD Grace Sembajwe, ScD Emmanuel d’Harcourt, MD THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iii Dissertation Abstract Title: The Impact of Climate Variability and Conflict on Childhood Diarrhea and Malnutrition in West Africa Author: Gillian Dunn Sponsor: Deborah Balk Objectives: This dissertation aims to contribute to our understanding of how climate variability and armed conflict impacts diarrheal disease and malnutrition among young children in West Africa. -

Systematic Country Diagnostic (Scd)

Document of The World Bank FOR OFFICIAL USE ONLY Public Disclosure Authorized Report No. 106725-GB GUINEA-BISSAU TURNING CHALLENGES INTO OPPORTUNITIES FOR POVERTY REDUCTION AND INCLUSIVE GROWTH Public Disclosure Authorized SYSTEMATIC COUNTRY DIAGNOSTIC (SCD) JUNE, 2016 Public Disclosure Authorized International Development Association Country Department AFCF1 Africa Region Public Disclosure Authorized International Finance Corporation Sub-Saharan Africa Department Multilateral Investment Guarantee Agency i ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS We would like to thank the following colleagues who have contributed through invaluable inputs, comments or both: Vera Songwe, Marie-Chantal Uwanyiligira, Philip English, Greg Toulmin, Francisco Campos, Zenaida Hernandez, Raja Bentaouet, Paolo Zacchia, Eric Lancelot, Johannes G. Hoogeveen, Ambar Narayan, Neeta G. Sirur, Sudharshan Canagarajah, Edson Correia Araujo, Melissa Merchant, Philippe Auffret, Axel Gastambide, Audrey Ifeyinwa Achonu, Eric Mabushi, Jerome Cretegny, Faheen Allibhoy, Tanya Yudelman, Giovanni Ruta, Isabelle Huynh, Upulee Iresha Dasanayake, Anta Loum Lo, Arthur Foch, Vincent Floreani, Audrey Ifeyinwa Achonu, Daniel Kirkwood, Eric Brintet, Kjetil Hansen, Alexandre Marc, Asbjorn Haland, Simona Ross, Marina Temudo, Pervaiz Rashid, Rasmane Ouedraogo, Charl Jooste, Daniel Valderrama, Samuel Freije and John Elder. We are especially thankful to Marcelo Leite Paiva who provided superb research assistance for the elaboration of this report. We also thank the peer reviewers: Trang Van Nguyen, Sebastien Dessus