Mutual and Co- Operative Approaches to Delivering Local

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

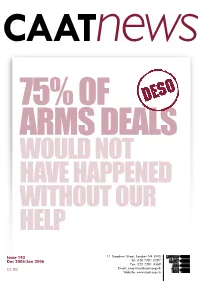

Issue 193 Dec 2005/Jan 2006 £1.00

CAATnews 75% OF ARMS DEALS WOULD NOT HAVE HAPPENED WITHOUT OUR HELP Issue 193 11 Goodwin Street, London N4 3HQ Dec 2005/Jan 2006 Tel: 020 7281 0297 Fax: 020 7281 4369 £1.00 Email: [email protected] Website: www.caat.org.uk CAATnews IN THIS ISSUE... Editor Melanie Jarman [email protected] Legal Consultant Glen Reynolds Proofreader Rachel Vaughan Design Richie Andrew Contributors Bristol CAAT, Kathryn Busby, Beccie D’Cunha, Ann Feltham, Nicholas Gilby, Anna Jones, Mike Lewis, James O’Nions, Ian Prichard, South Essex CAAT. Thank you also to our dedicated team of CAATnews stuffers. Printed by Russell Press on 100% recycled paper using only post consumer de-inked waste. Copy deadline for the next issue is 12 January 2006. We shall be posting it the week beginning 26 January 2006. Content of most website references are also available in print – contact CAAT National Gathering – see page 6 PATRICK DELANEY the CAAT office. Contributors to CAATnews express Countdown to DESO 3 their own opinions and do not necessarily reflect those of CAAT as an organisation. Contributors retain Arms Trade Shorts 4–5 copyright of all work used. CAAT was set up in 1974 and is a broad coalition of groups and News and updates 6 individuals working for the reduction and ultimate abolition of the Local campaign news and views 7 international arms trade, together with progressive demilitarisation within arms-producing countries. Cover story: DESO 8–9 Campaign Against Arms Trade 11 Goodwin Street, London N4 3HQ Feature: Arms trade treaty 10 tel: 020 7281 0297 fax: 020 7281 4369 email: [email protected] Reed campaign 11 web: www.caat.org.uk If you use Charities Aid Foundation cheques and would like to help TREAT Parliamentary 12 (Trust for Research and Education on Arms Trade), please send CAF Clean investment campaign 13 cheques, payable to TREAT, to the office. -

(Public Pack)Agenda Document for Programmes and Investment

Agenda Meeting: Programmes and Investment Committee Date: Wednesday 21 July 2021 Time: 10:00 Place: Microsoft Teams Members Prof Greg Clark CBE (Chair) Dr Nina Skorupska CBE Dr Nelson Ogunshakin OBE (Vice-Chair) Dr Lynn Sloman MBE Heidi Alexander Ben Story Mark Phillips Government Special Representative Becky Wood Copies of the papers and any attachments are available on tfl.gov.uk How We Are Governed. How decisions will be taken The 2020 regulations that provided the flexibility to hold and take decisions by meetings held using videoconference expired on 6 May 2021. While social distancing measures will be lifted ahead of this meeting, there has not been sufficient time to prepare for a return to physical meetings, therefore Members will attend a videoconference briefing held in lieu of a meeting of the Committee. Any decisions that need to be taken within the remit of the Committee will be discussed at the briefing and, in consultation with available Members, will be taken by the Chair using Chair’s Action. A note of the decisions taken, including the key issues discussed, will be published on tfl.gov.uk. As far as possible, TfL will run the briefing as if it were a meeting but without physical attendance at a specified venue by Members, staff, the public or press. Papers will be published in advance on tfl.gov.uk How We Are Governed Apart from any discussion of exempt information, the briefing will be webcast live for the public and press on TfL’s YouTube channel. A guide for the press and public on attending and reporting meetings of local government bodies, including the use of film, photography, social media and other v1 2020 means is available on www.london.gov.uk/sites/default/files/Openness-in- Meetings.pdf. -

Supplementary Information

HEIDI ALEXANDER POLITICAL EXPERIENCE 2010-2018 MEMBER OF PARLIAMENT FOR LEWISHAM EAST • Shadow Secretary of State for Health (2015-2016) • Deputy Shadow Minister for London (2013 – 2015) • Senior Opposition Whip (2013-2015) • Opposition Whip (2012-2013) • Member: ▪ Communities and Local Government Select Committee (2010-2012) ▪ Health Select Committee (2016-2017) ▪ Regulatory Reform Committee (2010-2012) ▪ Committee of Selection (2014-2015) • Co-founder & Director, Labour Campaign for the Single Market (2017-2018) 2006-2010 DEPUTY MAYOR & FULL-TIME CABINET MEMBER FOR REGENERATION LONDON BOROUGH OF LEWISHAM • Leadership responsibility for town centre redevelopment, transport, strategic housing and skills • London Councils Transport & Environment Committee Member (2006-2010) and TEC Executive Member (2006-2007) • Chair, Greater London Enterprise (2006-2008) • Director, Lewisham Local Education Partnership, responsible for the delivery of Lewisham’s Building Schools for the Future Programme (2007-2010) • Board Member, Thames Gateway London Partnership (2006-2010) 2004-2010 COUNCILLOR, LONDON BOROUGH OF LEWISHAM (EVELYN WARD) OTHER PROFESSIONAL EXPERIENCE 2005-2006 Campaign Co-ordinator, Clothes Aid 1999-2005 Parliamentary Researcher to Joan Ruddock MP 1998 6-month placement, Office of Cherie Booth QC, No.10 Downing St. 1996-1997 Holiday representative, First Choice Holidays EDUCATION 1998-1999 MA, European Urban and Regional Change (Distinction), Durham University 1993-1996 BA Hons, Geography (First Class), Durham University 1991-1993 New College Sixth Form, Swindon 1986-1991 Churchfields Comprehensive School, Swindon Page 1 This page is intentionally left blank Page 2 Statement by Heidi Alexander The Mayor’s vision for London is to deliver affordable public transport, healthier streets to encourage walking and cycling, and infrastructure that makes London fit for the future; a transport system that is the envy of the world. -

London Assembly Mayor’S Question Time – Thursday 18 July 2019 Transcript of Item 5 – Questions to the Mayor

Appendix 2 London Assembly Mayor’s Question Time – Thursday 18 July 2019 Transcript of Item 5 – Questions to the Mayor 2019/14512 - “Shocking... horrifying... slow”: the Government’s response to removing flammable cladding post-Grenfell Andrew Dismore AM In a recent interview with the Evening Standard, London Fire Commissioner Dany Cotton described the Government’s action on building fire safety since the Grenfell Tower fire as “shocking... horrifying... slow” (Evening Standard, 4 July 2019) and warned that Londoners are at risk because of aluminium composite material on high rise blocks. LFC Cotton continued: “I don’t think anyone in government has responded in a satisfactory manner. We need more to be done. We need for it to be taken seriously.” Do you agree with her appraisal? Sadiq Khan (Mayor of London): I fully agree with London Fire Commissioner Dany Cotton [QFSM] that the Government has failed to do anywhere near enough on building fire safety since the fire at Grenfell Tower. Today, the cross-party Housing, Communities and Local Government Committee published a damning report, which agrees that the Government has been - and I quote - “far too slow to react” to the Grenfell Tower tragedy. After the devastating fire in June 2017, the Government promised urgent action to make everyone safe. More than two years later, our building regulation system is still unfit for purpose, we still lack clarity on the basic questions of whether certain types of cladding are safe, and tens of thousands of people continue to live in homes that may be unsafe, with leaseholders facing huge bills for interim safety measures and other safety works. -

The Co-Operative Council

The Co-operative Council Sharing power: A new settlement between citizens and the state Lambeth’s proposal to become a Co-operative Council has generated a striking amount of passion, interest and debate over the past year. This new approach to public service delivery aims to reshape the settlement between citizens and the state by handing more power to local people so that a real partnership of equals can emerge. I believe the huge level of interest in our ideas both locally and nationally is driven by a genuine desire to find new and better ways to deliver public services in the 21st century. Although we publish this report at a time of unprecedented Government cuts in funding for local services, ours is not a cuts-driven agenda. I believe that if we do not make this change then the future of public services will be much more uncertain. The Co-operative Council draws inspiration from the values of fairness, accountability and responsibility that have driven progressive politics in this country for centuries. It is about putting the resources of the state at the disposal of citizens so that they can take control of the services they receive and the places where they live. More than just volunteering, it is about finding new ways in which citizens can participate in the decisions that affect their lives. The Co-operative Council is also not just about changing the council, it is about building more co-operative communities and realising that, for too long, the council has stood in the way rather than supported this development. -

(Notification of Withdrawal) Bill

1 House of Commons NOTICES OF AMENDMENTS given up to and including Friday 27 January 2017 New Amendments handed in are marked thus Amendments which will comply with the required notice period at their next appearance Amendments tabled since the last publication: 18-41 and NC53 to NC97 COMMITTEE OF THE WHOLE HOUSE EUROPEAN UNION (NOTIFICATION OF WITHDRAWAL) BILL NOTE This document includes all amendments tabled to date and includes any withdrawn amendments at the end. The amendments have been arranged in accordance with the European Union (Notification of Withdrawal) Bill Programme Motion to be proposed by Secretary David Davis. NEW CLAUSES AND NEW SCHEDULES RELATING TO PARLIAMENTARY SCRUTINY OF THE PROCESS FOR THE UNITED KINGDOM’S WITHDRAWAL FROM THE EUROPEAN UNION Jeremy Corbyn Mr Nicholas Brown Keir Starmer Paul Blomfield Jenny Chapman Matthew Pennycook Mr Graham Allen Ian Murray Ann Clwyd Valerie Vaz Heidi Alexander Stephen Timms NC3 To move the following Clause— 2 Committee of the whole House: 27 January 2017 European Union (Notification of Withdrawal) Bill, continued “Parliamentary oversight of negotiations Before issuing any notification under Article 50(2) of the Treaty on European Union the Prime Minister shall give an undertaking to— (a) lay before each House of Parliament periodic reports, at intervals of no more than two months on the progress of the negotiations under Article 50 of the Treaty on European Union; (b) lay before each House of Parliament as soon as reasonably practicable a copy in English of any document which the European Council or the European Commission has provided to the European Parliament or any committee of the European Parliament relating to the negotiations; (c) make arrangements for Parliamentary scrutiny of confidential documents.” Member’s explanatory statement This new clause establishes powers through which the UK Parliament can scrutinise the UK Government throughout the negotiations. -

(Public Pack)Agenda Document for West London Economic Prosperity

Public Document Pack West London Economic Prosperity Board Wednesday 18 September 2019 at 3.00 pm Board Room, London First, Middlesex House, 34-42 Cleveland St, W1T 1 This page is intentionally left blank Agenda Item 1 LONDON BOROUGH OF EALING . The West London Economic Prosperity Board Venue: Board Room, London First, Middlesex House, 34-42 Cleveland St, W1T 4JE Date and Time: Wednesday, 18 September 2019 at 15:00 Membership Councillor Thomas (Barnet), Councillor Tatler (Brent), Councillor Bell - Chair (Ealing) Councillor Henson (Harrow), Councillor Curran (Hounslow and Councillor Cowan (Hammersmith & Fulham) AGENDA Open to the Public and Press 1 Apologies for Absence - 2 Declarations of Interest - 3 Urgent Matters - Page 1 Page 1 of 80 4 Matters to be Considered in Private - Item 8 (Appendix A) contains information that is exempt from disclosure by virtue of Paragraph 3 of Part 1 of Schedule 12A of the Local Government Act 1972. 5 Minutes - To approve as a correct record the minutes of the meeting held on 19 June 2019. No. Minutes of the Meeting Held on 19 June 2019 3 - 6 6 Shared Transport Priorities 7 - 10 7 West London Orbital - Progress and Next Steps 11 - 20 8 Update on WLA Health and Employment 21 - 46 Programmes 9 Draft Vision For Growth 47 - 58 10 Strategic Investment Pool 2019-20 59 - 74 11 EPB Work Programme 75 - 80 12 Date of Next Meeting - The dates of the meetings for the remainder of the Municipal Year 2019/20 are: 20 November 2019 26 February 2020 Page 2 Page 2 of 80 West London Economic Prosperity Board – 19 June 2019 West London Economic Prosperity Board Held in the Board Room, London First, Middlesex House, 34-42 Cleveland Street, London, W1 4JE. -

Weekly List & Decisions

Planning Weekly List & Decisions Appeals (Received/Determined) and Planning Applications & Notifications (Validated/Determined) Week Ending 26/04/2019 The attached list contains Planning and related applications being considered by the Council, acting as the Local Planning Authority. Details have been entered on the Statutory Register of Applications. Online application details and associated documents can be viewed via Public Access from the Lambeth Planning Internet site, https://www.lambeth.gov.uk/planning-and-building- control/planning-applications/search-planning-applications. A facility is also provided to comment on applications pending consideration. We recommend that you submit comments online. You will be automatically provided with a receipt for your correspondence, be able to track and monitor the progress of each application and, check the 21 day consultation deadline. Under the Local Government (Access to Information) Act 1985, any comments made are open to inspection by the public and in the event of an Appeal will be referred to the Planning Inspectorate. Confidential comments cannot be taken into account in determining an application. Application Descriptions The letters at the end of each reference indicate the type of application being considered. ADV = Advertisement Application P3J = Prior Approval Retail/Betting/Payday Loan to C3 CON = Conservation Area Consent P3N = Prior Approval Specified Sui Generis uses to C3 CLLB = Certificate of Lawfulness Listed Building P3O = Prior Approval Office to Residential DET = Approval -

Statement of Persons Nominated, Notice of Poll and Situation of Polling Stations

STATEMENT OF PERSONS NOMINATED, NOTICE OF POLL AND SITUATION OF POLLING STATIONS Election of a Member of Parliament for Dulwich and West Norwood Borough Constituency Notice is hereby given that: 1. A poll for the election of a Member of Parliament for Dulwich and West Norwood Borough will be held on Thursday 12 December 2019, between the hours of 7:00 am and 10:00 pm. 2. One Member of Parliament is to be elected. 3. The names, home addresses and descriptions of the Candidates remaining validly nominated for election and the names of all persons signing the Candidates nomination paper are as follows: Names of Signatories Names of Signatories Names of Signatories Name of Description (if Home Address Proposers(+), Seconders(++) & Proposers(+), Seconders(++) & Proposers(+), Seconders(++) & Candidate any) Assentors Assentors Assentors BARTLEY Flat A, 23 Tooting Green Party Pollock Christian (+) (++) (+) (++) Jonathan Charles Bec Gardens, Florence R(+) Nicholas E(++) London, SW16 Lee Stevan R H Rahmatova Nazira 1QY Alton Adam J Reynolds Matthew F Rosenfeld David Elliott Peter G Wood Thomas W Rodgers Emily HAYES (Address in the Labour Party Clinch Lucian C F(+) Donald Alice P(++) (+) (++) (+) (++) Helen Elizabeth Dulwich and West Wood Penelope B Tait Ann S Norwood Wykes Sarah J Doherty Mary T constituency) Kilraine Karen C Britton Carol J Deckers Dowber George Helen L Max K HODGSON (Address in the Christian Peoples Jackson Rowe Robert D(++) (+) (++) (+) (++) Anthony Paul Dulwich and West Alliance Matthew S(+) Banya Budget Norwood Rowe Valerie -

Planning Applications Committee 03 December 2019 Second Addendum: Amendments and Additional Information on Agenda Items

PLANNING APPLICATIONS COMMITTEE 03 DECEMBER 2019 SECOND ADDENDUM: AMENDMENTS AND ADDITIONAL INFORMATION ON AGENDA ITEMS Page Number Report Changes Decision Letter Changes ITEM 4 Applications 19/01304/FUL & 19/01305/LB – 8 Albert Embankment Pages 167, and Amendments to report No 168 ‘Affordable Housing and An addendum note has been provided by BNPP in relation to viability. Housing Mix’ Officer comment: BNPP can comment on this should committee members have any questions. Page 221 No ‘Planning The contribution for implementation of Low Traffic Neighbourhood on local streets in the area is Obligations and £164,000. CIL’ Page 228, Additional Condition (amended to suggested additional condition set out in First Addendum) Yes Conditions Noise Mitigation and Control for Noise Generating Uses 43 Prior to the commencement of development of each relevant block containing an A4 or D2 use hereby permitted, a scheme of noise assessment and scheme of mitigation must be undertaken and shall be submitted to and approved in writing by the Local Planning Authority to ensure that the noise impacts from all/the relevant A4 and D2 uses shall be suitably mitigated and that the spaces shall be suitably ventilated to enable effective delivery of the proposed scheme. A suitably qualified independent person must undertake all work and the scheme of mitigation. The scheme shall ensure that operational noise levels from the commercial use do not exceed NR25 Leq,5mins between 22:00 – 07:00hrs within potentially adversely affected residential or other noise sensitive locations during typical activities. The scheme must include details of stages of validation during the construction phase and a post construction scheme of validation and measurement to demonstrate substantive compliance. -

Election of Councillors for the Bishop`S Ward London Borough of Lambeth Thursday 3 May 2018 Statement of Persons Nominated & Notice of Poll

ELECTION OF COUNCILLORS FOR THE BISHOP`S WARD LONDON BOROUGH OF LAMBETH THURSDAY 3 MAY 2018 STATEMENT OF PERSONS NOMINATED & NOTICE OF POLL A poll will be held on Thursday 3 May 2018 between 7am and 10pm to elect three Councillors in Bishop`s Ward. Name of Assentors Name of Candidate Home Address Description (if any) Proposer(+) Seconder(++) ARMSTRONG 56C Ufford Street Green Party Drummond Rita + Harrison Emma R P London Whitfield Helen ++ Berthelot Philippe O Michael Richard O`connell Margaret James Laurie SE1 8QB Morgan Edna Drummond Joanne E Davies Josephine C P Drummond Desmond BELLIS 16 Stannary Street Conservative Party Candidate Whelan John A + Hammerbeck Roland T K Kennington Mazure Ivor J ++ Warland Philip J James Howard Jenkin Anne C Nicoll Sheila London Jenkin Bernard C Jones Theodore D W SE11 4AA Jacob Francis P T Wacher Charles CHAMBERS Flat C Conservative Party Candidate Whelan John A + Hammerbeck Roland T K 19 Aulton Place Mazure Ivor J ++ Warland Philip J Glyn Edward Jenkin Anne C Nicoll Sheila London Jenkin Bernard C Jones Theodore D W SE11 4AG Jacob Francis P T Wacher Charles CRAIG 34 Chelsham Road Labour Party Mosley Kitty O + Aytek Raife London Bryant Caroline T ++ Boyson-Smith Edward J Kevin Daniel Rice Scott R Bridge Richard W SW4 6NP Boyle Andrew Philipp Karen S Anderson Pauline M Tootill David H DOGUS 80 North Block Labour Party Mosley Kitty O + Aytek Raife 5 Chicheley Street Bryant Caroline T ++ Boyson-Smith Edward J Ibrahim Rice Scott R Bridge Richard W Lambeth Boyle Andrew Philipp Karen S SE1 7PN Anderson Pauline -

Geneva Conventions and Its Additional Protocols, and Is Further Supplemented by the Laws, Regulations, and Guidelines of the European Union

THE UNITED KINGDOM‘S DUTY UNDER INTERNATIONAL HUMANITARIAN LAW TO ENSURE NON-DISCRIMINATORY MEDICAL CARE TO WOMEN AND GIRLS RAPED IN ARMED CONFLICT, INCLUDING ACCESS TO SAFE ABORTION SERVICES Excerpts of UK, EU and International Laws, Policies & Practices Relevant to this Duty Updated as of October 8, 2013 Preface The duty of the United Kingdom (―UK‖) to respect international law, and in particular international humanitarian law, is firmly rooted in its body of domestic law which implements the Geneva Conventions and its Additional Protocols, and is further supplemented by the laws, regulations, and guidelines of the European Union. For women raped in armed conflict, abortion is a legal right under international humanitarian law (―IHL‖). Girls and women raped in armed conflict are ―protected persons‖ under the Geneva Conventions and are entitled, as the ―wounded and sick,‖ to ―receive to the fullest extent practicable and with the least possible delay, the medical care and attention required by their condition.‖ This care must also be non-discriminatory. To deny a medical service to pregnant women (abortion), while offering everything needed for victims who are male or who aren‘t pregnant, is a violation of this requirement of non-discrimination. Therefore, IHL imposes an absolute and affirmative duty to provide the option of abortion to rape victims in humanitarian aid settings; failing to do so violates the Geneva Conventions, its Additional Protocols, and customary international law. These protections are further supported by international human rights law. The Committee against Torture and the Human Rights Committee have both declared the denial of abortion to be torture or cruel, inhuman, and degrading treatment in certain situations.